Recommended

Following a couple of days of bad news about the faltering Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) announced on March 10 that the bank was put into receivership for restructuring. Just a few days before, SBV was reportedly the 16th largest bank in the United States and was granted an investment grade category by the rating agencies (AA3 rating by Moody’s and BBB by Standard & Poor’s). On March 12, the US Treasury, Federal Reserve, and FDIC announced actions on SVB and one more bank, Signature Bank, based on systemic risk concerns.

Although the actions by the US authorities have so far calmed local markets, fears of contagion around the globe continue (witness Credit Suisse’s current troubles), and many observers are asking the obvious questions: Where were the regulators in the lead up to the crisis? What happened to the strict regulations imposed on banks after the Global Financial Crisis, including Basel III, the international standards for capital adequacy, stress testing, and liquidity requirements? Why did these regulations fail to prevent SVB’s collapse? Or should the blame fall on the Fed for raising interest rates too high, too quickly, destabilizing the financial system?

These questions are extremely relevant for emerging markets. As in the US and other advanced economies, most emerging markets have implemented Basel III regulations and are fighting inflation through increases in interest rates. My view is that the Fed and the central banks of most emerging markets are doing their job, using the tools at their disposal for controlling inflation and protecting financial stability, but there are faults in existent regulatory and supervisory frameworks that weaken supervisors’ ability to detect the build-up of problems in the banking systems.

First, on monetary policy. Unquestionably, a precondition for effective monetary policy is a sound banking system. There are multiple examples in advanced and emerging markets where, in the context of weak financial systems, sharp and sustained increases in interest rates ended in severe banking crises. The only way for a central bank to minimize the potential trade-off between price stability and financial stability resulting from interest rate hikes is to ensure that banking systems are sound in the first place. Where financial systems are strong, tighter monetary policy to control inflation does not need to end in deep financial problems, as central bankers around the world have acknowledged.

So, what is behind a sound banking system? Largely, a combination of good financial regulation and good risk management at the bank level. By now, evidence abounds on the poor managerial quality of SVB to the extent that its top executives are being sued for fraud. But there certainly were failures in supervision and regulation. Bank regulators and supervisors in emerging markets should be looking closely at their own banking systems now with the lessons of SVB’s collapse in mind.

Underwhelming supervisory oversight

A well-known early warning sign of bank problems is a rapid expansion in bank assets, which signals an increase in risk-taking. Normally, asset expansion takes the form of fast growth in credit (I say “normally” because the main role of banks is to take deposits to extend loans). In the case of SVB, more than 50 percent of its assets were bonds, mostly Treasury bonds. That in itself was a red flag: a commercial bank that focuses on buying bonds rather than on lending is weakening the value of its franchise, which lies on its capacity to undertake maturity transformation from short-term deposits to long-term loans. In doing so, sound banks focus on monitoring the quality of debtors to ensure that they make good on their payments, rather than betting on the performance of securities.

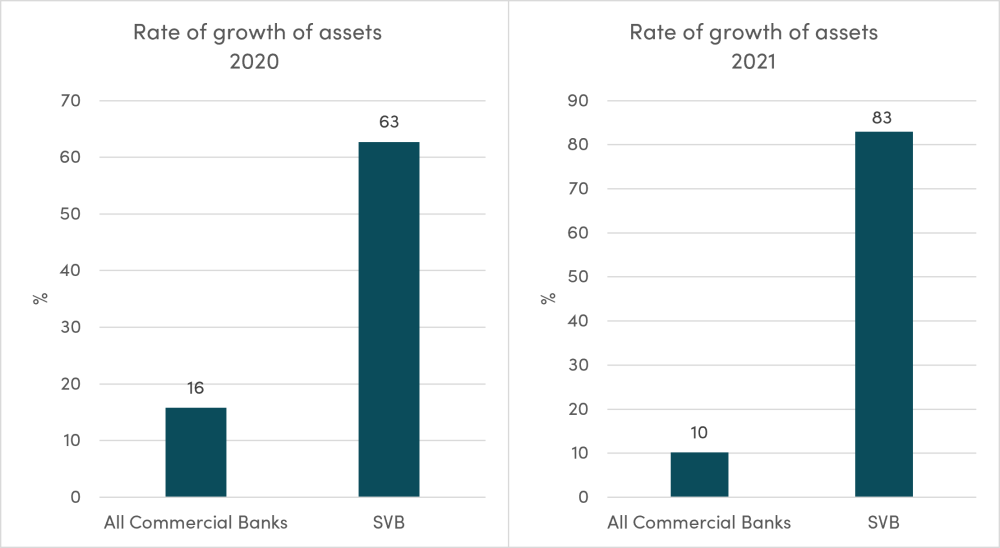

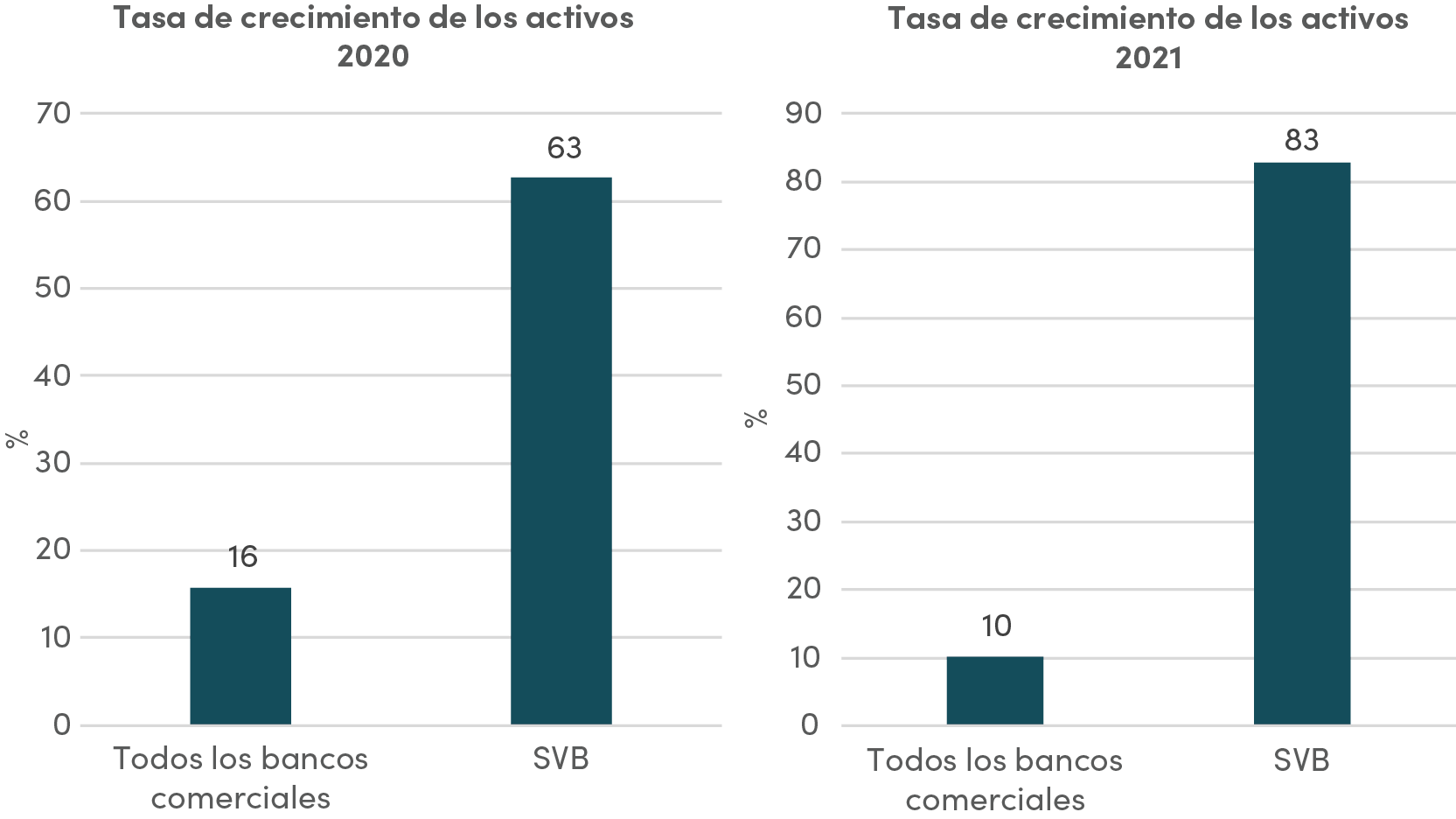

During the peak of the COVID period, overall bank deposits grew significantly, partly reflecting the increase in precautionary savings. But SVB assets ballooned well-above the overall system. As shown in Figure 1, SVB assets increased by over 60 percent in 2020 and by over 80 percent in 2021. By comparison, the rates of growth for the entire US banking system increased by 16 percent and 10 percent respectively. As startups in the tech sector were booming during the pandemic, deposits into SVB—known as a bank for tech companies—also skyrocketed. Since most of these deposits came from small firms, they surpassed the maximum amount that the FDIC insures, namely, $250,000. In other words, most of the deposits—a shocking 90 percent—were uninsured. Rather than channelizing funds into loans, SVB sharply increased its holding of long-term Treasury bonds.

Figure 1. Growth in SVB assets, 2020 and 2021

Sources: Fed St. Louis Fed and YCharts

Were supervisors and rating agencies lulled into a false sense of security by the fact that US Treasury bond are considered the world’s safest asset, certainly much safer than loans, and that they are defined as high-quality liquid assets in Basel III? It’s hard to know, but the fact is that they tolerated the large accumulation of these assets. And yes, they are highly liquid in the sense that there is a huge active global market for them, but as with any other fixed-income security, their price declines when interest rates rise. That is, they are subject to market risks. And when there is a run of deposits (as was the case for SVB’s uninsured depositors), the value of those bonds may not be sufficient to meet depositors’ demands for their money.

How can banks protect against market risks arising from increasing interest rates? Through hedging, usually done through interest rate swaps. Allegedly, those hedges were nowhere to be found in the case of SVB—a tremendous failure of risk management by SVB’s managers that supervisors did not catch.

In sum, the list of bad bank practices that supervisors failed to either detect or promptly correct is impressively long. On the liability side: concentration of deposits in the volatile tech industry and an overwhelming majority of uninsured depositors. This combination left the depositors base prone to a run at the first sign of problems. On the asset side: high concentration in securities subject to market risk and lack of hedges for these risks. How did supervisors miss the writings on the wall?

What about cracks in the regulatory framework?

Were supervisors and rating agencies misled by SVB’s compliance with key regulations? In short, yes.

A bit of recent history may help here: most countries around the world have committed to implement Basel III, the global regulatory set of standards guiding banks’ activities, especially capital and liquidity requirements, put forward after the Global Financial Crisis. Basel III recommendations, however, apply only to internationally active banks. It is up to the discretion of countries’ authorities to apply the regulations to all banks. Complementing the Dodd-Frank regulations of 2010, in 2013 the US chose to adopt Basel III, applying liquidity requirements only to large and internationally active banks, which are considered to be a potential risk to the financial sector. However, for the majority of banks not classified as large enough, the 2013 regulation applies a modified version of Basel III, with less strict, but still stringent liquidity requirements.[i] In both Dodd-Frank and Basel III, stress testing requirements were a central part of the regulation.

But in 2018, the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act relaxed some of these regulatory standards, including two in particular. First, under the original Dodd-Frank legislation, banks with consolidated assets of $50 billion had to comply with strict regulatory and stress testing standards. The 2018 modification drastically raised the threshold to $250 billion. With consolidated assets fluctuating around $230 billion, SVB no longer had to comply with the original Dodd-Frank regulation. Second, after 2018, only banks with assets above $250 billion were required to conduct stress testing.[ii] Now, when banks’ need stress testing to gauge their resilience to increases in interest rates the most, the regulation is lacking.

In addition, some regulation was temporary relaxed in 2020 to support bank lending during the COVID-19 period. Specifically, the 2020 “Current Losses Transition Rule” provided banks with the option to delay for two years the increase in bank capital requirements resulting from the adoption of a new—and better—accounting standard (the CECL—Current Expected Credit Losses). This option also granted banks three additional transition years to smooth the adjustment of capital. While relaxation of certain regulatory standards was common practice around the world during the pandemic, it was quite unusual to find such long period of postponement.

Did all US banks elected to use this five-year transition option that, effectively, reduced incentives to raise additional capital? Most likely not. Reports suggest that large banks had already started to implement the new regulation before the transition option was issued and considered it more costly to go backwards and then forward again. Not surprisingly, SVB elected to use the five-year option.

Thus, the mix of poor risk management in some banking institutions, weakened regulation, and faulty supervision created a perfect storm for the eruption of severe banking problems. SVB was the natural disaster to emerge.

Where do emerging markets stand?

The good news first: in contrast to the US, most emerging markets have chosen to apply Basel III regulatory standards to all banks, not just the largest banks, although the state of implementation of these rules varies significantly between countries. Importantly, while authorities in most countries relaxed some banking regulations during the COVID-19 period to support the provision of loans to the real economy (including the rules on loan classification and provisioning for non-performing loans), these relaxations have expired by now in most countries.

However, learning from the SVB experience, there are some red flags that should alert supervisors in emerging markets. Two issues, which we discussed in Making Basel III Work for Emerging Markets and Developing Countries, deserve particular attention.

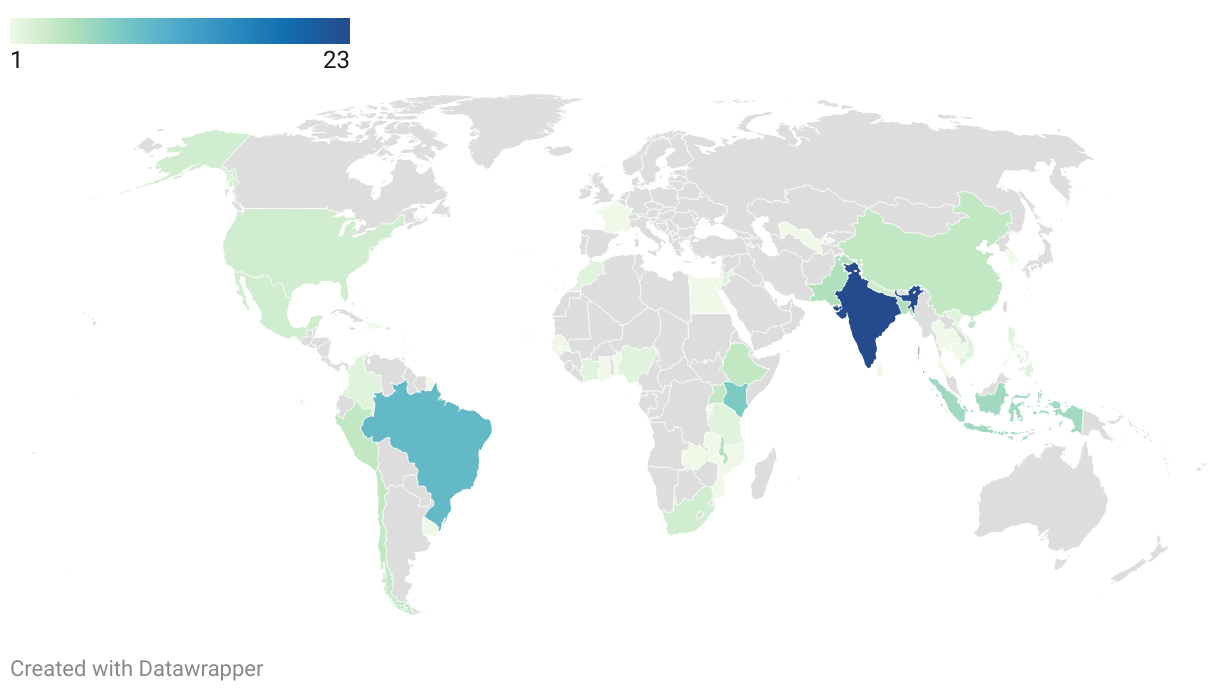

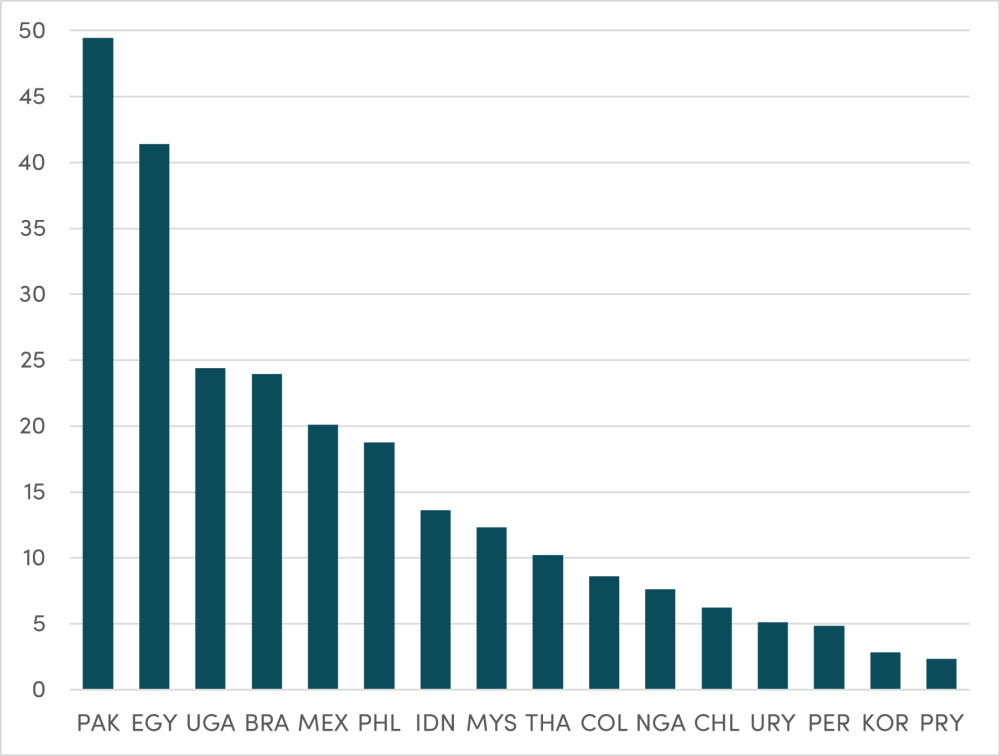

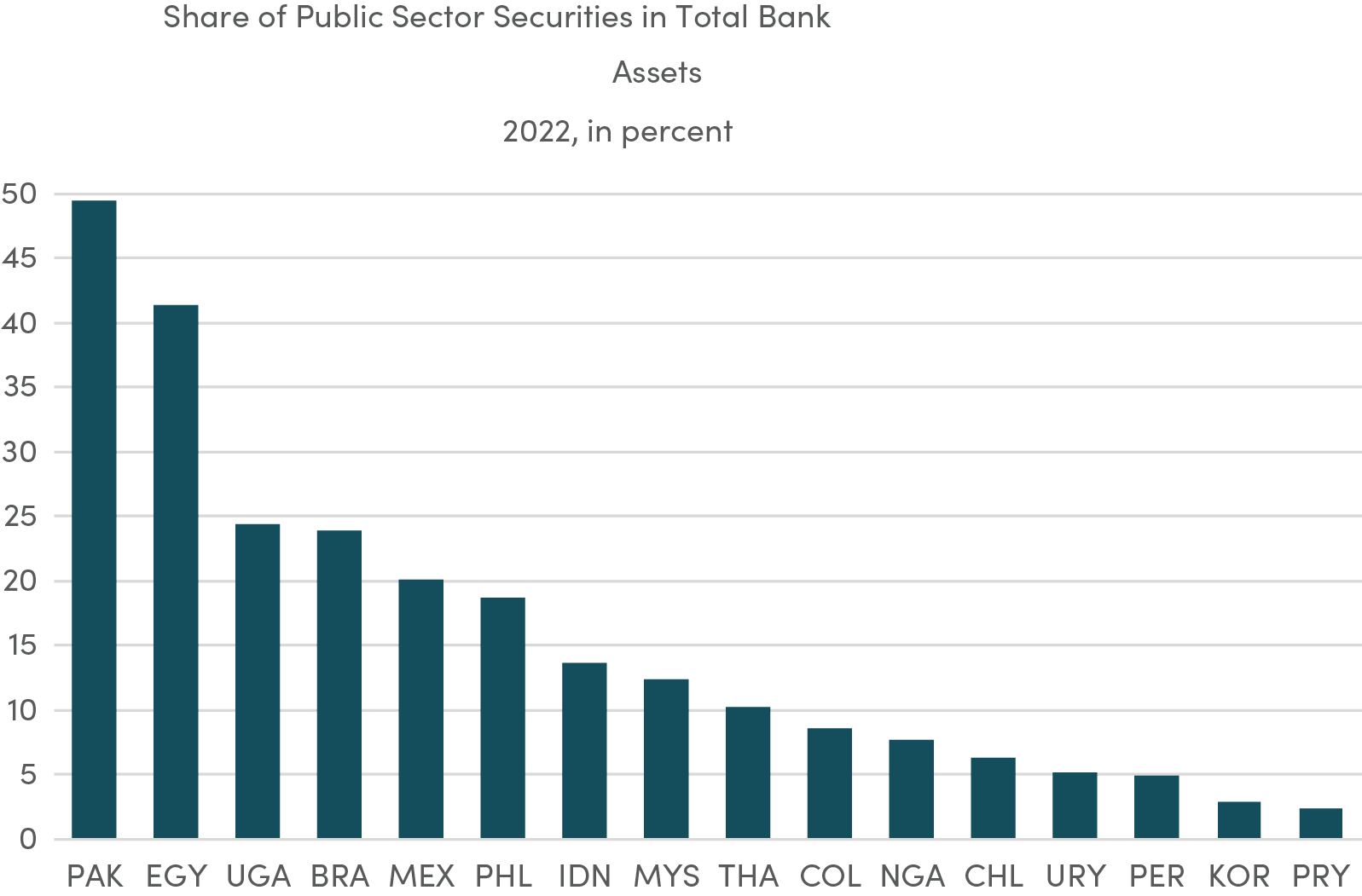

First, large holdings of government bonds in banks’ balance sheets are not a rare occurrence in many emerging markets. As shown in Figure 2, in countries such as Pakistan and Egypt the share of public sector securities in total bank assets surpasses 40 percent and ratios above 20 percent are not uncommon.

Figure 2. Share of public sector securities in total bank assets, 2022, in percent

Source: IMF-IFS

Just as in the US, central banks in these countries—and in most emerging markets—are raising interest rates to fight inflation. Are banks in countries with large holding of government paper hedging for market risk? Are they and their supervisors conducting the necessary stress tests to identify whether banks are really liquid and can stand an unanticipated withdrawal of funds? Answer to these questions may identify where the next banking crisis would occur.

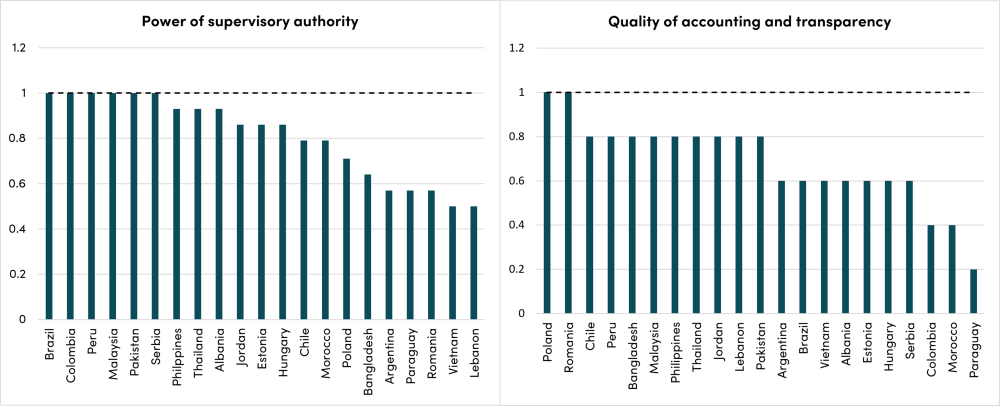

Second, although regulation is improving, serious deficiencies remain in accounting, transparency, and the quality of supervision in many countries. Figure 3 shows two indices based on data from Angiles et al. (2019) ranging from 0 to 1 where larger values represent higher quality of the indicator. The variable Powers of Supervisory Authority measures the independence and capacity of the supervisory authority to look after financial stability and intervene and restructure banks when necessary. Quality of Accounting and Transparency measures the extent to which banks disclose information in a transparent way using international accounting standards.

Figure 3. Quality of supervision and accounting and transparency in emerging markets

Source: Update of Montoro and Rojas-Suarez (2011), based on Anginer et al (2019)

Clearly, there are some countries in the sample where serious improvements are needed.[iii] Even if regulation is strong, weaknesses in supervision could lead to failures in identifying the accumulation of excessive risk in the financial system and result in banking crises.

There’s a common saying that every cloud has a silver lining. If there’s a silver lining to the SVB collapse, it may be that, hopefully, bank regulators and supervisors around the world will learn from it. For the majority of emerging markets, where previous episodes of banking crises were devastating and turned back the clock on development progress, it is crucial to promptly correct deficiencies. It is essential that emerging markets allow their central banks to use the interest rate tool to fight inflation without fearing major disruptions in their financial systems.

[i] Basel III Liquidity Coverage ratio requires banks to hold sufficient amount of high-quality liquidity to meet net cash outflows during a 30-day period under an acute stress scenario. In the US, for banks that were not classified as large enough, the regulations complementing Dodd-Frank required banks to hold sufficient high-quality liquidity to meet 70 percent of withdrawals under an acute stress scenario. To estimate liquidity requirements, banks were expected to conduct stress tests. One obvious stress scenario, of course, is significant and sustained increases in interest rates.

[ii] In implementing the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency stated in 2019: “Specifically, the final rule revises the minimum threshold for national banks and Federal savings associations to conduct stress tests from $10 billion to $250 billion, revises the frequency by which certain national banks and Federal savings associations will be required to conduct stress tests, and reduces the number of required stress testing scenarios from three to two.”

[iii] Since this is 2019 data—the most recent I was able to find with comprehensive information for a large number of countries—it is possible that important improvements have been implemented in some countries in the most recent years.

Nayke Montgomery was responsible for data collection, analysis and visualization, and research background, as well as Spanish translation.

Tras un par de días de malas noticias sobre la situación del Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), la Corporación Federal de Seguro de Depósitos (FDIC) anunció el 10 de marzo que el banco había sido puesto en liquidación para su reestructuración. Solo unos días antes, SVB era presuntamente el decimosexto banco más grande de los Estados Unidos y se le otorgó una calificación de grado de inversión por parte de las agencias calificadoras (calificación AA3 de Moody's y BBB de Standard & Poor's). El 12 de marzo, el Tesoro de los Estados Unidos, la Reserva Federal y la FDIC anunciaron medidas para SVB y Signature Bank, debido a preocupaciones por riesgo sistémico.

Aunque hasta ahora las acciones de las autoridades estadounidenses han calmado los mercados locales, los temores de contagio en todo el mundo continúan (como lo demuestran los problemas actuales de Credit Suisse), y muchos analistas están haciendo las preguntas obvias: ¿Dónde estaban los reguladores antes de la crisis? ¿Qué sucedió con las regulaciones estrictas impuestas a los bancos después de la Crisis Financiera Global, incluyendo a Basilea III, los estándares internacionales de adecuación de capital, pruebas de estrés y requisitos de liquidez? ¿Por qué estas regulaciones no lograron evitar el colapso del SVB? ¿O deberíamos culpar a la Fed por elevar las tasas de interés agresivamente, desestabilizando el sistema financiero?

Estas preguntas son extremadamente relevantes para los países emergentes. Al igual que en Estados Unidos y otras economías avanzadas, la mayoría de los países emergentes han implementado las regulaciones de Basilea III y están luchando contra la inflación mediante aumentos en las tasas de interés. En mi opinión, la Fed y los bancos centrales de la mayoría de los países emergentes están haciendo su trabajo para controlar la inflación y proteger la estabilidad financiera, pero existen fallas en los marcos regulatorios y de supervisión que debilitan la capacidad de los supervisores para detectar la acumulación de problemas en los sistemas bancarios.

En primer lugar, en cuanto a política monetaria, una condición previa para su efectividad es indudablemente un sistema bancario sólido. Existen múltiples ejemplos en países avanzados y emergentes donde, en el contexto de sistemas financieros débiles, aumentos bruscos y sostenidos en las tasas de interés terminaron en graves crisis bancarias. La única forma para que un banco central minimice el posible trade-off entre la estabilidad de precios y la estabilidad financiera resultante de las subidas de tasas de interés, es asegurarse de que los sistemas bancarios sean sólidos desde el principio. Cuando los sistemas financieros son fuertes, una política monetaria más restrictiva para controlar la inflación no tiene por qué terminar en problemas financieros severos, como han reconocido los banqueros centrales de todo el mundo.

Entonces, ¿qué hay detrás de un sistema bancario sólido? En gran medida, una combinación de buena regulación financiera y una buena gestión del riesgo a nivel bancario. De momento, ya hay evidencia sobre la baja calidad gerencial de SVB hasta el punto de que sus altos ejecutivos están siendo demandados por fraude. Pero ciertamente hubo fallas en la supervisión y regulación. Los reguladores y supervisores bancarios de los países emergentes deberían estar examinando de cerca sus propios sistemas bancarios ahora con las lecciones del colapso de SVB en mente.

Supervisión deficiente

Un signo de alerta de problemas bancarios es una rápida expansión en los activos bancarios, lo que indica un aumento en la toma de riesgos. Normalmente, la expansión de activos toma la forma de un rápido crecimiento en el crédito (digo "normalmente" porque el papel principal de los bancos es tomar depósitos para extender préstamos). En el caso de SVB, más del 50 por ciento de sus activos eran bonos, principalmente bonos del Tesoro. Eso en sí mismo fue una señal de advertencia: un banco comercial que se enfoca en comprar bonos en lugar de prestar está debilitando el valor de su franquicia, que radica en su capacidad para llevar a cabo la transformación de madurez de depósitos a corto plazo a préstamos a largo plazo. Al hacer esto, los bancos sólidos se centran en monitorear la calidad de los deudores para asegurarse de que cumplan con sus pagos, en lugar de apostar por el rendimiento de los valores.

Durante el pico de la pandemia del COVID, los depósitos bancarios en general crecieron significativamente, reflejando en parte el aumento en los ahorros precautorios. Sin embargo, los activos de SVB crecieron muy por encima del total del sistema bancario. Como se muestra en la Figura 1, los activos de SVB aumentaron más del 60 por ciento en 2020 y más del 80 por ciento en 2021. En comparación, las tasas de crecimiento para todo el sistema bancario de los Estados Unidos fueron un 16 por ciento y un 10 por ciento, respectivamente. Con el auge de las nuevas empresas del sector tecnológico durante la pandemia, los depósitos en SVB, conocido como un banco para empresas tecnológicas, también se dispararon. Como la mayoría de estos depósitos provenían de empresas (relativamente pequeñas), superaron el monto máximo que asegura la FDIC, es decir, $250,000. En otras palabras, la mayoría de los depósitos, sorprendentemente el 90 por ciento, no estaban asegurados. En lugar de canalizar fondos en préstamos, SVB aumentó fuertemente su tenencia de bonos del Tesoro a largo plazo.

Figure 1. Crecimiento en los activos de SVB, 2020 y 2021

fuente: Fred St. Louis Fed and YCharts

¿Se confundieron los supervisores y las agencias de calificación de riesgo por el hecho de que los bonos del Tesoro de EE. UU. se consideran el activo más seguro del mundo, ciertamente mucho más seguro que los préstamos, y que se definen como activos líquidos de alta calidad en Basilea III? Es difícil saberlo, pero el hecho es que toleraron la gran acumulación de estos activos. Y sí, son altamente líquidos en el sentido de que existe un gran mercado global activo para ellos, pero al igual que cualquier otro valor de renta fija, su precio disminuye cuando suben las tasas de interés.Es decir, están sujetos a riesgos de mercado. Y cuando hay una corrida bancaria (como fue el caso de los depositantes no asegurados de SVB), el valor de esos bonos puede no ser suficiente para satisfacer las demandas de los depositantes por su dinero.

¿Cómo pueden los bancos protegerse contra los riesgos del mercado derivados del aumento de las tasas de interés? A través de la cobertura (hedging), normalmente realizada mediante swaps de tasas de interés. Según indican algunos reportes, esas coberturas no se llevaron a cabo en el caso de SVB, lo que constituye un fracaso tremendo en la gestión de riesgos por parte de los directivos de SVB que los supervisores no detectaron.

En resumen, la lista de malas prácticas bancarias que los supervisores no pudieron detectar o corregir de manera oportuna es impresionantemente larga. Por el lado de los pasivos: la concentración de depósitos en la volátil industria tecnológica y una abrumadora mayoría de depositantes no asegurados. Esta combinación dejó la base de depositantes propensa a una corrida a la primera señal de problemas. En cuanto a los activos: alta concentración en valores sujetos a riesgos de mercado y falta de coberturas para estos riesgos. ¿Cómo es que los supervisores no vieron las señales de advertencia?

¿Qué hay de los huecos en el marco regulatorio?

¿Se engañaron los supervisores y las agencias calificadoras de riesgo dado que SVB cumplía con las regulaciones clave? En pocas palabras, sí.

Un poco de historia reciente puede ayudar: la mayoría de los países del mundo se han comprometido a implementar Basilea III, el conjunto de estándares regulatorios globales que guían las actividades bancarias, especialmente los requisitos de capital y liquidez, propuestos después de la crisis financiera mundial. Sin embargo, las recomendaciones de Basilea III solo se aplican a los bancos internacionalmente activos. Depende de la discreción de las autoridades de los países aplicar las regulaciones a todos los bancos. Complementando las regulaciones de Dodd-Frank de 2010, en 2013 Estados Unidos decidió adoptar Basilea III, aplicando requisitos de liquidez solo a los bancos grandes e internacionalmente activos, que se consideran un riesgo potencial para el sector financiero. Sin embargo, para la mayoría de los bancos que no se clasifican como suficientemente grandes, la regulación de 2013 aplica una versión modificada de Basilea III, con requisitos de liquidez menos estrictos, pero aún rigurosos. [1] Tanto en Dodd-Frank como en Basilea III, los requisitos de pruebas de estrés eran una parte central de la regulación.

Pero en 2018, la Ley de Crecimiento Económico, Alivio Regulatorio y Protección al Consumidor relajó algunas de estas normas regulatorias, incluyendo dos en particular. En primer lugar, según la ley original de Dodd-Frank, los bancos con activos consolidados por $50 mil millones debían cumplir con normas regulatorias y pruebas de estrés estrictas. La modificación de 2018 aumentó drásticamente el umbral a $250 mil millones. Con activos consolidados fluctuando alrededor de los $230 mil millones, SVB ya no tuvo que cumplir con la regulación original de Dodd-Frank. En segundo lugar, después de 2018, solo se requería que los bancos con activos por encima de $250 mil millones realizaran pruebas de estrés. [2] Precisamente en estos momentos, cuando los bancos necesitan pruebas de estrés para medir su capacidad de resistir aumentos en las tasas de interés, la regulación es deficiente.

Además, algunas regulaciones se relajaron temporalmente en 2020 para apoyar la concesión de préstamos bancarios durante el período de COVID-19. Específicamente, la "Regla de Transición de Pérdidas Actuales" de 2020 otorgó a los bancos la opción de retrasar durante dos años el aumento en los requisitos de capital bancario resultantes de la adopción de un nuevo, y mejor, estándar de contabilidad (la CECL - Pérdidas Crediticias Esperadas Actuales). Esta opción también otorgó a los bancos tres años adicionales de transición para suavizar el ajuste de capital. Si bien la relajación de ciertos estándares regulatorios era práctica común en todo el mundo durante la pandemia, fue bastante inusual encontrar un período tan largo de aplazamiento.

¿Eligieron todos los bancos de EE. UU. utilizar esta opción de transición de cinco años que efectivamente redujo los incentivos para recaudar capital adicional? Lo más probable es que no. Los informes sugieren que los bancos grandes ya habían comenzado a implementar la nueva regulación de capital antes de que se emitiera la opción de transición, por lo que consideraron que sería más costoso retroceder y luego avanzar nuevamente. Como era de esperar, SVB optó por utilizar la opción de cinco años.

Por lo tanto, la combinación de una mala gestión del riesgo en algunas instituciones bancarias, una regulación debilitada y una supervisión deficiente creó una tormenta perfecta para el surgimiento de graves problemas bancarios. SVB fue el desastre natural que surgió de esto.

¿En dónde se encuentran los países emergentes?

Primero las buenas noticias: a diferencia de los Estados Unidos, la mayoría de los países emergentes han optado por aplicar los estándares regulatorios de Basel III a todos los bancos, no solo a los más grandes, aunque el estado de implementación de estas reglas varía significativamente entre países. Es importante destacar que, si bien las autoridades en la mayoría de los países relajaron algunas regulaciones bancarias durante el período de COVID-19 para apoyar la provisión de préstamos a la economía real (incluyendo las normas sobre clasificación de préstamos y provisión para préstamos no productivos), estas relajaciones ya han expirado en la mayoría ellos.

Sin embargo, aprendiendo de la experiencia de SVB, hay algunas señales de alerta que deberían llamar la atención de los supervisores en los mercados emergentes. Dos temas importantes que discutimos en profundidad en nuestro reporte sobre los efectos de Basilea III en países emergentes y en vías de desarrollo, merecen atención especial.

En primer lugar, en muchos países emergentes se observa grandes tenencias de bonos gubernamentales en los balances bancarios. Como se muestra en la Figura 2, en países como Pakistán y Egipto, la proporción de bonos del sector público en el total de activos bancarios supera el 40 por ciento y en otros el porcentaje se encuentra por encima del 20 por ciento.

Figure 2

Source: IMF-IFS

Al igual que en Estados Unidos, los bancos centrales en estos países, y en la mayoría de los países emergentes, están elevando las tasas de interés para combatir la inflación. ¿Están los bancos en países con grandes tenencias de papel gubernamental cubriendo el riesgo de mercado? ¿Están ellos y sus supervisores realizando las pruebas de estrés necesarias para identificar si los bancos son realmente líquidos y pueden soportar una retirada imprevista de fondos? Las respuestas a estas preguntas podrían identificar dónde se producirá la próxima crisis bancaria.

En segundo lugar, aunque la regulación está mejorando, aún existen deficiencias graves en contabilidad, transparencia y calidad de supervisión en muchos países. La Figura 3 muestra dos índices basados en datos de Angiles et al. (2019) que van de 0 a 1, donde valores más altos representan mayor calidad de supervisión. La variable Poderes de la Autoridad Supervisora mide la independencia y capacidad de la autoridad supervisora para velar por la estabilidad financiera e intervenir y reestructurar bancos cuando sea necesario. La variable Calidad de Contabilidad y Transparencia mide hasta qué punto los bancos divulgan información de manera transparente utilizando normas contables internacionales.

Figure 3. Calidad de la supervisión, contabilidad y transparencia en los mercados emergentes

Source: Update of Montoro and Rojas-Suarez (2011), based on Anginer et al (2019)

Claramente, hay algunos países en la muestra que necesitan mejoras significativas [3] Incluso si la regulación es sólida, las debilidades en la supervisión podrían llevar a que no se identificaran correctamente la acumulaciones de riesgos excesivos en el sistema financiero y dar lugar a crisis bancarias.

Hay un refrán popular que dice que no hay mal que por bien no venga. Algo bueno que pudiera derivarse del colapso de SVB, es que los reguladores y supervisores bancarios de todo el mundo aprendan de lo ocurrido. Para la mayoría de los países emergentes, donde episodios anteriores de crisis bancarias fueron devastadores y retrocedieron el progreso del desarrollo, es crucial corregir las deficiencias rápidamente. Es esencial que los bancos centrales de los países emergentes puedan utilizar la herramienta de tasa de interés para combatir la inflación sin temor a que se originen serios problemas en sus sistemas financieros.

[1] El ratio de cobertura de liquidez de Basel III requiere que los bancos mantengan una cantidad suficiente de liquidez de alta calidad para satisfacer las salidas netas de efectivo durante un período de 30 días en un escenario de estrés agudo. En los Estados Unidos, para los bancos que no se clasificaron como suficientemente grandes, las regulaciones complementarias a Dodd-Frank requerían que los bancos mantuvieran suficiente liquidez de alta calidad para satisfacer el 70 por ciento de los retiros en un escenario de estrés agudo. Para estimar los requisitos de liquidez, se esperaba que los bancos realizaran pruebas de estrés. Un escenario de estrés obvio, por supuesto, es el aumento significativo y sostenido de las tasas de interés

[2] En la implementación de la Ley de Crecimiento Económico, Alivio Regulatorio y Protección al Consumidor, la Oficina del Contralor de la Moneda declaró en 2019: "Específicamente, la regla final aumenta de $10 mil millones a $250 mil millones el umbral mínimo para que los bancos nacionales y asociaciones federales de ahorro realicen pruebas de estrés, revisa la frecuencia con la que ciertos bancos nacionales y asociaciones federales de ahorro deberán realizar pruebas de estrés y reduce el número de escenarios de prueba de estrés requeridos de tres a dos".

[3] Dado que estos datos corresponden a 2019 (lo más reciente que pude encontrar con información completa para un gran número de países), es posible que se hayan implementado mejoras importantes en algunos países en los últimos años.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.

Image credit for social media/web: Adobe Stock