Recommended

After deciding that the UK can only afford to spend around £10 billion in aid as a result of “difficult fiscal circumstances,” the UK Treasury is reportedly proposing further cuts to aid programmes solely to accommodate some unusual accounting items under the 0.5 aid percent target: the use of UK’s allocation of new Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) and debt relief on export credits extended to Sudan decades ago. These items do not adversely affect the UK’s fiscal position, and do not change the return on aid programmes, and so there is no economic or fiscal reason for them to lead to further cuts. Yet further cuts—potentially as much as £2 billion in 2022—would happen if the Treasury insisted on counting these items towards the target.

Accounting vs reality

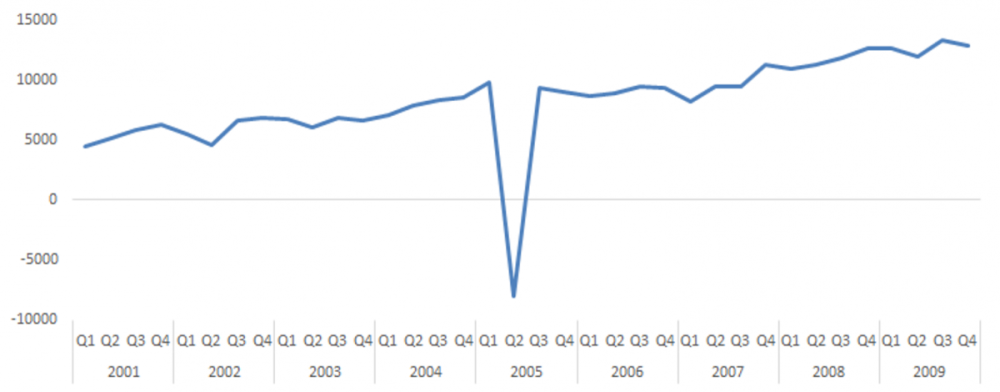

In the second quarter of 2005, there was a dramatic fall in UK government investment. The UK government went from investing about £10 billion in the previous quarter to minus £8 billion, implying that it was losing assets. To date, this has been the biggest drop in government investment since comparable records began. Yet, the Treasury did nothing at the time to mitigate this. No special measures were taken to try and maintain investment and there was no soul-searching about the causes of the collapse. Why was the Treasury so sanguine?

Figure 1: General Government Investment (Gross fixed capital formation), £m

Source: ONS (series identifier RPZG)

The reason is that this fall in investment was entirely cosmetic: all that had happened was that British Nuclear Fuels Ltd was reclassified from being a public to a private entity, and so the fall in government assets was matched by an equal increase in private sector assets (there is a corresponding spike in private sector investment data). The government, quite sensibly, did nothing to try to ensure that the series remained smooth. Investments did not suddenly and temporarily become more or less profitable, nor did they become more or less affordable. Nothing relevant had changed, so it would have been absurd for the government to change its spending decisions in light of this accounting anomaly.

Yet there is a risk that the government is about to let accounting take precedence over reality in meeting the aid target. After deciding that the UK can only afford to spend around £10 billion in aid, the Treasury is reportedly proposing further cuts in real aid spending solely to accommodate some unusual (but ODA-eligible) accounting items under the 0.5 percent target. These accounting items have no bearing on the affordability of, or expected benefits from, spending the initial £10 billion. In contrast to 2005, it seems the Treasury is about to let accounting anomalies dictate real-world decisions, and as a result, worthwhile programmes risk being cut for no other reason than to keep ODA constant as a percentage of GNI. There is no economic rationale for this, “difficult fiscal circumstances'' or otherwise.

This is not a new concern: there have long been critics of the UK’s attempt to precision-target 0.7 percent, when in some years it might be sensible to spend more (or less, but multilaterals can easily absorb and spend additional ODA effectively, reducing this problem). But the timing and scale of some unusually large items of ODA-eligible expenditures would make the attempt particularly damaging in the next couple of years. Brutal cuts have already been made across the board (including “priority” areas) following the decision to lower the target to 0.5; there is hardly any “fluff” left to cut (if there was any to begin with). Projects that can be delayed already have been, and may need to be cut anyway, given the recent government decision to delay a return to a 0.7 percent target. And the items under discussion are one-off, implying a need to immediately ramp spending back up again the following year. This would be the mirror image of the government choosing to fill the (arbitrary) gap in figure 1.

The first potential one-off accounting item on the horizon is the use of the UK’s SDR allocation at the IMF. The UK is discussing lending some of its new SDR allocation to the IMF’s Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust Fund (PRGT) to allow it to expand its lending to LICs. This has been discussed extensively elsewhere, but the key consideration here is that using a share of the UK’s SDRs to increase PRGT lending will not necessarily cost the UK anything, and so it won’t make any difference to what the UK can afford to spend elsewhere.

The UK had decided that it could spend roughly £10 billion on ODA before the new SDR allocation is made. This allocation is the closest thing the world gets to free money, and, therefore, whatever the UK does with its new SDRs, it can still afford the original £10 billion: there is no sensible argument for reducing the pre-SDR-allocation aid budget. This matters because of the potential scale. Even if the UK only used one fifth of its allocation (which would be £4 billion), we estimate around £1.2 billion could be billed as ODA, necessitating a dramatic see-sawing in the budgets of remaining programmes if counted towards the target. This is already an overestimate of donor effort given the way the “grant element” of lending is measured. It is also completely against the spirit of the SDR allocation: the new allocation was not agreed to help the UK repair its finances, but to raise additional liquidity for poorer countries. Cutting other programmes to accommodate SDR lending will mean the PRGT financing boost is not additional, contrary to assertions from the Chancellor.

The second is the possibility of cancelling some debt owed to the UK Export Finance agency (UKEF) by Sudan. The total amount owed to the UK is £861 million, over eight percent of the amount of ODA the UK will spend in 2021. It might be thought that cancelling debt has an implication for the UK’s finances: surely, given that this was money the UK was owed, its spending power has been slightly reduced by giving up on getting this money back? This may have been true once. But the debt dates back to at least the early 1990s, and so it is absurd to believe that the UK is still budgeting on the assumption that it will be paid back. In fact, given that it is owed to the export credit agency, the loan is probably on UKEF’s books precisely because a private creditor (whose loan was guaranteed by UKEF) gave up on it decades ago. The government might have made a loss when it originally assumed the bad debt from the creditor, but even then, this would have been covered by insurance premiums received by UKEF in exchange for such guarantees, and it is not relevant for budgeting today. (In fact, UKEF boasts on its website that it operates “at no net cost to the taxpayer.") At this point, cancelling this debt is now essentially a matter of accounting, with no real-world impact on the UK’s ability to spend aid.

Furthermore, the UK’s International Development Act, which provides ministers with the power to spend development assistance, requires that “the assistance is likely to contribute to a reduction in poverty”. It’s hard to see how this financial transfer will achieve that principle. The inclusion of debt relief on export credits as ODA is highly controversial partly for this reason, and has endured decades of criticism, from previous Development Assistance Committee (DAC) chairs, previous DAC statisticians, independent experts, and countless civil society organisations.

Don’t let accounting rules dictate spending

The public reaction to the cut from 0.7 to 0.5 percent of GNI in the UK suggests that the Treasury needn’t be too worried about the political impact of slightly exceeding the 0.5 percent target temporarily (with even the most aid-hostile news outlets seeming uneasy about the potential impacts on human welfare). But if that is the concern, the UK is not obliged to report activities as ODA just because they are eligible. Luxembourg has long declined to report its in-donor refugee spend on principle, and the US engages in lots of R&D activities that may be regarded as ODA by other countries. Statisticians may baulk at the inconsistencies caused by differing adherence to the rules, but they can probably swallow their misgivings if it prevents unnecessary and damaging cuts in the order of billions of dollars.

Otherwise, arguments about fiscal circumstances — already difficult to believe — look disingenuous. The aid projects at risk were good value-for-money before the SDR allocation or potential Sudanese debt forgiveness, and they remain so now. They are also no less affordable. The decision to cut the aid budget was wrong: it will make barely any difference to the UK’s deficit but a huge difference to those missing out on education or vaccines. But, there were undeniable real-world changes relevant to the decision: the ballooning deficit resulting from the COVID-19 response is no mere accounting illusion. However, if the government insists on jamming these new accounting items under the already-slashed 0.5 percent target, there can be no doubt that rather than difficult fiscal circumstances, ideological opposition to aid and Treasury bean-counting were the real motives.

This would mean more cuts to valuable programmes that the government claims to prioritise, such as girl’s education, vaccinations, humanitarian response, and a host of other worthwhile projects. The Treasury has already won the battle over the agreed target: ensuring that we will spend 0.5 percent of GNI on the aid budget rather than 0.7 percent for the foreseeable future. The government should ensure that both debt-relief on export credits and any use of SDRs are additional to prevent further harm either to its aid partners or the UK’s standing in the world.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.