Since the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) began implementing the steep cuts to the UK’s aid budget imposed upon it by the Treasury, much of the immediate reaction has focused on the immense human cost of reducing aid during a global pandemic. But as soon as we learnt that the aid budget would be thrown into the volcano to appease the fiscal gods, it should have been clear that even with a perfect process of prioritisation many good things would have to be sacrificed. There was never enough fat to avoid cutting the lean.

What has not been clear, however, is if the cuts are being used to realise a new vision of what UK aid is for—whether what is left behind is just a smaller version of what existed before the cuts, or a qualitatively different approach to using aid. Investigating this is made difficult by FCDO releasing information in a fashion that renders detailed comparison with past allocations impossible. Nevertheless, a few patterns are visible. This blog sets out where it looks like the portfolio is going, and the next round of challenges it faces.

ODA may be coming ‘home’ to FCDO—for now

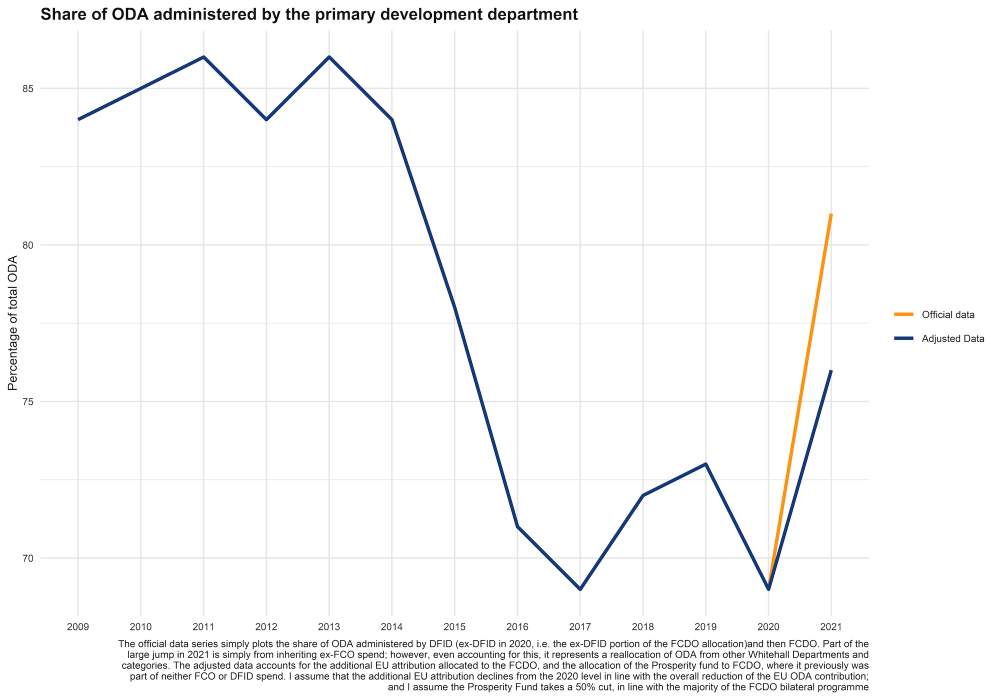

Since the 0.7 percent legislation passed into law, an increasing proportion of UK official development assistance (ODA) has been captured by non-development departments, leading to a reimaging of the UK’s development approach—focusing more directly on benefits to the UK, and less on poverty reduction and the welfare of the poorest people and countries. The initial shape of the cuts suggests a partial undoing of the damage done by this mission creep and dilution of focus. The Foreign Secretary had control over the allocation of ODA across Whitehall and used it to reconsolidate spending under the management of the primary development department—once the Department for International Development (DFID) and now FCDO. If we take the government’s numbers at face value, the proportion of the aid budget administered by the primary development department has risen to 81 percent, from a nadir of 69 percent the previous year, and not far off the level it routinely reached in the pre-0.7 years. Even once we adjust the official figures for some creative accounting around EU development spending attribution and the Prosperity Fund, it still represents a recovery to 76 percent.

This is a good thing: FCDO inherited DFID’s machinery for rigorously pursuing value for money in aid spending, through its evidence-informed business cases, internal peer review, and scored annual reviews. Reflecting this, independent evaluation results for DFID were systematically stronger than the rest of Whitehall. Deeper cuts for less effective departments suggest an increase in overall portfolio quality, and an intention on the part of FCDO to retain control of ODA in the future. This will prove difficult, as other government departments have grown accustomed to using ODA to fund things that were once non-ODA, and will look to resume doing so at the earliest opportunity. Navigating this is a challenge FCDO will need to face head-on.

2021 is the first true FCDO budget, and hints at the future

Nevertheless, much remains uncertain. Even as it takes a larger share of ODA, FCDO must implement stinging cuts. But to understand what the future of FCDO (and with it much of the UK’s development budget) might be, we need to look at the distribution of what remains.

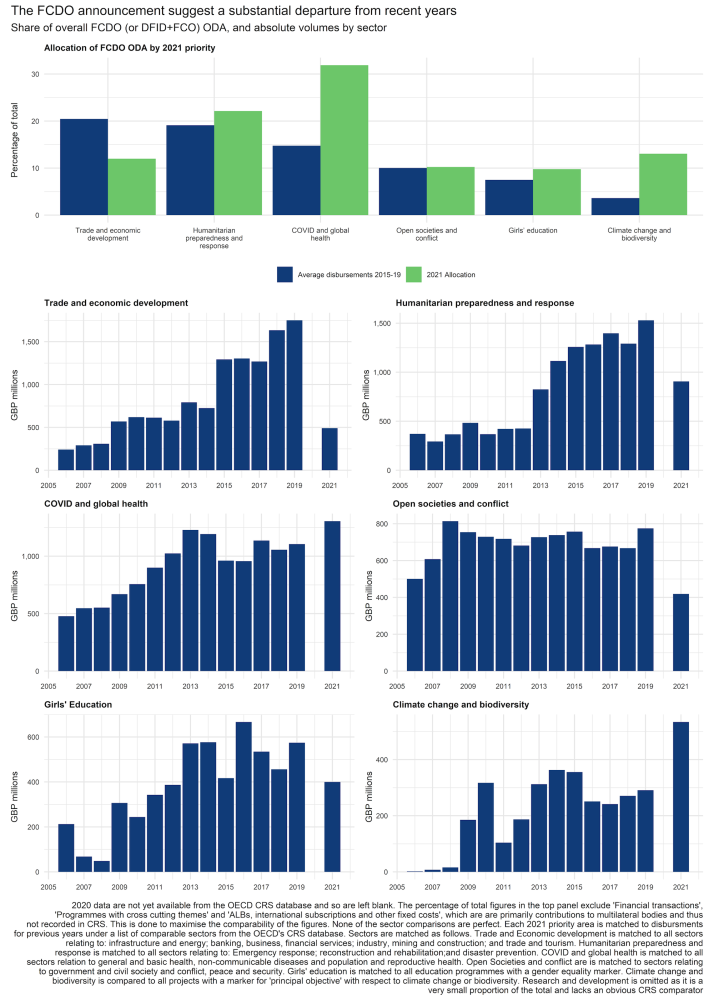

Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab announced seven priority areas FCDO would focus on in the future, namely climate change and biodiversity; COVID-19 and global health; girls’ education; humanitarian preparedness and response; open societies and conflict; science, research and technology; and trade and economic development. Additional categories of spend appear to be primarily multilateral contributions, subscriptions to other organisations, or allocations to non-departmental bodies. The seven areas are new aggregations, which resist comparison to existing data. Despite this, with a great deal of detective work and a little creativity in aggregating sectors from the OECD’s project-level Common Reporting Standard (CRS) database it is possible to make an indicative comparison between the 2021 portfolio and the structure of spending by DFID and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (the two agencies that were merged to form the new FCDO) in recent years. It isn’t perfect, but it does give us a glimpse at what is changing.

Examining FCDO’s 2021 allocations against this out-of-focus background suggests that it has made choices that are simultaneously very much of their time and a nod to the future. It’s no surprise that in a year that the world is battling a global pandemic and in which the UK is hosting a major international climate conference sees dramatic pivots towards global health and climate change. This makes sense for 2021, but likely also represents a genuine realignment of what UK ODA will be used for, at least in the medium term. The COP2026 climate conference is unlikely to pass by without new multi-year commitments, and investment will be required to repair the direct and indirect costs of COVID-19, as well as to build a system that reduces the risk of or improves capacity to respond to future pandemics. Climate change and global health are the only two areas which appear to be getting an absolute increase over previous years. In other cases, FCDO priorities have taken severe cuts in absolute spending, but nevertheless received a modest increase in the share of bilateral ODA. That is the case for girls’ education and humanitarian preparedness. It is equally striking that, of the priority areas, trade and economic development has taken a substantial proportionate cut (to say nothing of the brutal nature of its absolute reduction), while open societies and conflict has been protected as a share of bilateral aid.

These changes tentatively suggest three strategic choices made in reshaping the portfolio. First, if the sector definitions and explanations in this letter can be taken at face value, FCDO has not so much established seven priorities as made them the almost exclusive domain of the funding over which it manages directly. After removing allocations reported to be primarily for development banks, non-departmental public bodies, and the financial transactions that were ring-fenced by the Treasury, virtually everything else is allocated to these seven areas. Assuming no creative accounting has been applied to rebrand projects that are primarily about agricultural productivity or water and sanitation as ‘climate’ or ‘health’ activities, this represents a much sharper focus of FCDO spending than ever before. In the previous five years, the proportion of spending on these sectors from FCDO’s bilateral budget has been around 75 percent—still substantial, but not quite so ruthlessly focused. We can argue about whether these are the right sectors, but the principle of being more focused with diminished resources is sensible.

Secondly, the list of priority sectors suggests that FCDO is pivoting towards global public goods. The COVID and global health and climate categories are by far the biggest winners in 2021, and also the two most closely associated with activities that generate returns outside of poor countries as well as within their borders. This isn’t necessarily in itself good or bad, but unless done carefully (as Charles Kenny has written elsewhere) it can be less pro-poor, at odds with the Foreign Secretary’s stated ambition to focus on the bottom billion.

Thirdly, FCDO has made a sudden and dramatic break with the trend in both DFID and the FCO of increasing spending on economic development activities in the last few years. The allocation made in 2021 is much smaller both in absolute and proportionate terms than that of recent years. This makes sense in many ways: the increase in spending was at odds with the stated priorities of DFID’s 2017 Economic Development Strategy, most of which were about changing how and where non-aid finance flows. An uncomfortably large proportion of this spending was administered through large, centrally managed programmes of the type Stefan Dercon and I argued against the use of. Importantly, this doesn’t mean neglecting the sector altogether. Spending less itself and instead using expertise, diplomacy and non-FCDO levers such as CDC (the UK’s development finance institution) and contributions to the multilateral development banks to support economic development is a much more sensible approach than large prosperity fund projects that are too small to shift either UK or partner country outcomes.

Collectively, these three strategic shifts provide a hint at what FCDO might be aiming at: to be one part pre-0.7 DFID, when funding was focused on sectors where the volume of spending available might make a practical difference (i.e. much more on the human development sectors and less on economic development); one-part vehicle for the pursuit of global public goods that the UK has a foreign and development policy interest in; and one (relatively small) part funder of the traditional domain of foreign policy, under the ‘Open Societies’ category.

2022 and beyond could be better—or worse

This isn’t a bad vision for what FCDO should look like in the future. 2021 is dominated by brutal cuts and the associated deserved opprobrium, but in the long term, it matters more that what is built back from the rubble of the cuts is sensible. For the organisation tentatively outlined above to succeed, though, it will need to navigate three pressing challenges.

The most obvious is the circling vultures over the aid budget. There are voices in government who want the cuts imposed this year to be permanent and the remnants to be distributed across Whitehall much more evenly. While the FCDO won the first battle by imposing stiff cuts on other government departments, no doubt these same departments are now sharpening their knives in preparation for the forthcoming spending review. Rather than inviting a bloodbath which could leave all sides wounded and the portion of ODA allocated to other departments once again spent poorly, FCDO should pre-empt the battle by proposing cross-government platforms for those aspects of spending where collaboration makes sense. Most commonly this will be where technical expertise and policy leadership is either split or resides primarily in a non-development department, but the expertise in managing, delivering, and evaluating projects in developing countries and in line with rules and legislation governing ODA lies with FCDO.

Another pressing challenge is internal: how to define and organise spending on global public goods in a way that is an efficient use of resources for development outcomes and makes a dent in the global challenge they are targeted at. This is not a trivial problem. Often, spending in poor countries is an inefficient way of solving global problems. At the same time, addressing global problems is often not the number one priority for poor countries themselves, when the same resources could be used to address local problems with larger welfare implications for the poor. FCDO need to find a way to spend on global public goods that makes a difference to global problems while simultaneously solving the local problems that matter most to poor countries requires. Their forthcoming development strategy should address this directly.

Thirdly, applying the approach to evidence, evaluation and learning that DFID was rightly celebrated for will be much more difficult for FCDO, focusing as it will on global public goods and joint development/foreign policy objectives as well as traditional development problems. The institutional set up inherited from DFID, which is centred around evidence-based business cases, internal peer review, and evaluation, works best for those concrete development outcomes where a rich research literature exists, where the goals and objectives are easily stated and defined, and where indicators and targets are well-suited. Applying this to global public goods runs into a problem of evidence and of objective definition: what weight should be applied to the global vs. the development-specific return? This is a policy choice no government has been in a hurry to make explicit in recent years. Equally, the research literature on foreign policy interventions is less amenable to evaluation of expected impact.

The 2021 aid cuts are an extremely costly way of achieving not very much for the UK’s public finances; that the Treasury insisted on them demonstrates the extremely low value they ascribe to the welfare gains that ODA achieves abroad. Given this, the choices FCDO make now matter enormously. There is no guarantee that budgets will rise to allow the recovery of activities that have been cut; nor that they will not be cut further in the future. The strategic approach taken by FCDO will determine how effective UK ODA is in the future. 2021 will be a mess, but if they can navigate these challenges, they may yet emerge with a portfolio that makes an impact, at least where it still focuses.

This blog benefited from excellent comments and support from Euan Ritchie, Atousa Tahmasebi, Mark Plant, and Ian Mitchell. All errors and omissions remain the author’s.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.