Recommended

Blog Post

Blog Post

Germany supports the universal basic education goals of the SDGs, wants to eradicate global poverty and promotes multilateralism as the way to achieve these goals. So why does it route most of its education aid to higher education? Why does most of its aid go to upper-middle-income countries and its own federal states? And why does it allocate such a small share of its aid budget to multilateral institutions?

2022 is a year of change for Germany. The country has inaugurated its first new head of state for 16 years, and its first three-party coalition since 1957. It takes over the G7 presidency for the first time since the SDGs were adopted. And this all comes amid a global pandemic, with a climate emergency at the top of the international agenda.

But there is a constant: Germany will remain the most generous donor to global education. For nine of the past ten years it allocated more aid money than any other donor to education. In 2019, $1 in every $4 of education aid globally came from Germany.

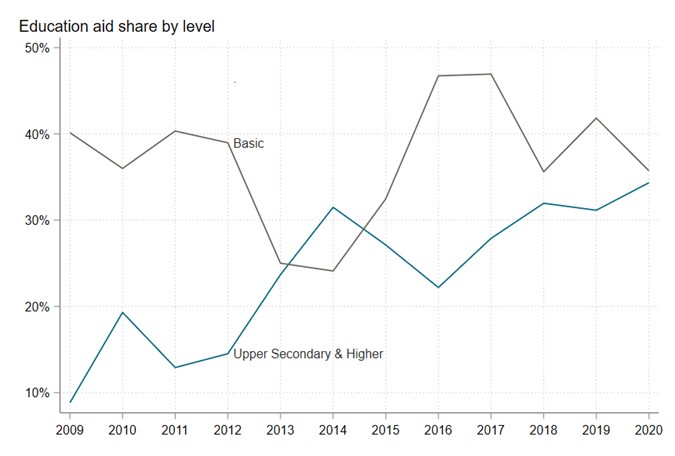

Yet Germany’s approach to global education is unusual. As a simple indicator Germany spends only 10 percent of its education aid on basic education while other G7 members spend close to 50 percent. And, despite its strong reputation for international cooperation, Germany ranked 26 of 29 countries in QuODA 2021 for core support to multilaterals.

In this blog we dig deeper into Germany’s approach to education aid and consider the ways in which its development architecture works.

1. Germany is unusual in the way it spends its education aid

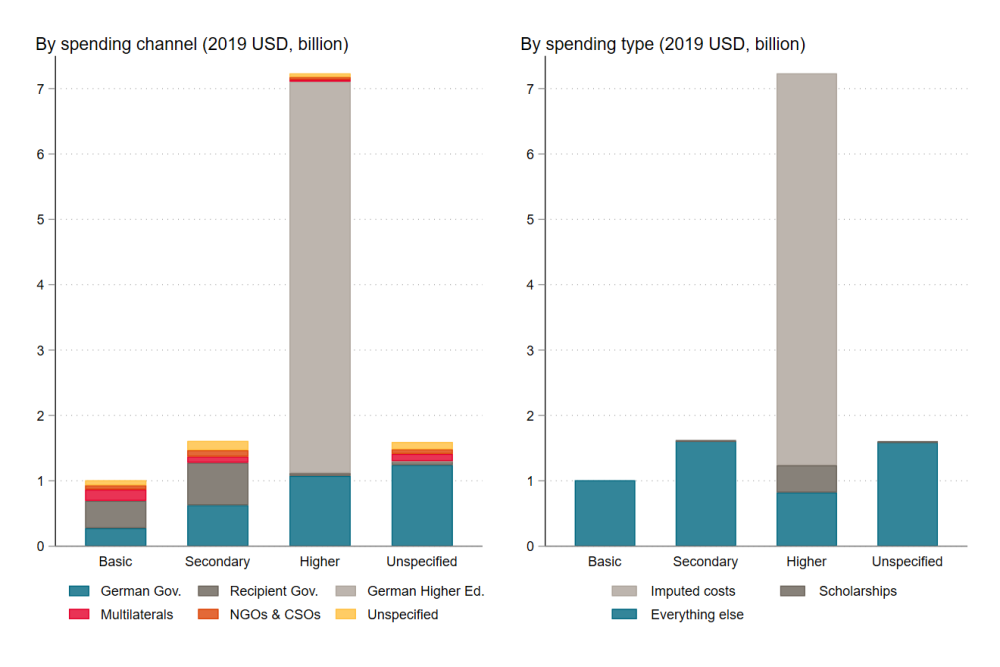

The principle underpinning Germany’s education aid spending is that its engagement is most effective when it “can draw on a wealth of experience and successful models in our own country… as is the case with Germany’s dual system of vocational education.” This is reflected in the large majority of spending that Germany routes to higher education—seven times as much as it spends on basic education. And it’s important to be clear up front how its aid to higher education breaks down.

First, scholarships—covering travel, insurance and living costs—are awarded for international students to study in Germany (6 percent of higher education spending). These amounted to $414 million over the past 5 years, covering about 5,000 scholarships each year. While these students are studying in German universities, the government will also ‘impute’ the costs of their tuition as aid (it is not a service that comes for free, although it is free for the student).

But there is a second, far larger, bucket of ‘imputed’ tuition costs (83 percent). University is fee-free in Germany (in all but one state) making it attractive for international study. In 2019 there were 163,540 students from aid-eligible countries studying in Germany. The implicit tuition cost for every single one of these students is counted as aid. This is permitted by the OECD, so long as a few conditions are met including that “the presence of students reflects the implementation of a conscious policy of development co-operation by the host country”. Which in Germany’s case, it does. It’s really this part, the imputed tuition costs for people who choose to study in Germany, that propels Germany’s education aid.

And third, everything else (11 percent). Including things like technical cooperation to develop vocational training programmes, research prizes, programs to improve university tuition and facilities in recipient countries and so on.

Figure 1. Where did the last five years of German education aid go?

Source: OECD-DAC CRS data for 2015-2019. Note: Figure shows the total USD disbursement over the period 2015-2019, shown in 2019 USD.

2. Germany has spent over $1.5 billion on international scholarships in the past decade, but we know very little about the impact of these programs

Germany’s preference for higher education scholarships and funding for international students is frequently criticised. Very large sums are allocated to a few individuals. And those that are eligible are likely to be from the richest backgrounds in their home countries. Men are more likely to have received a scholarship financed by German aid (but this has improved over time).

On the other hand, evidence on the role of migration in development suggests that scholarships could actually be a great buy. For each additional year of higher education funded by a scholarship we can expect large labour market returns. And more migration enabled by a scholarship can generate income increases of several hundreds of percent. Educational migration is likely to substantially benefit the country of origin, via remittances or by encouraging others’ investments in schooling. There are also benefits to the host country if graduates remain there following their scholarship—indeed Germany’s Minister for Economic Affairs stated earlier this month that the country will need more immigration to prevent severe labour shortages.

But the thing is, despite Germany’s outlay, very little evidence has been generated on the causal impacts of aid-financed scholarships. There have been “tracer studies” and alumni surveys. But even the best of these seem to go no further than reporting on the outcomes of scholarship winners who elected to complete the survey. We know a fair bit about the benefits of international migration and the returns to schooling in one's home country, but very little about the potential for aid-financed scholarships as a development tool.

Germany can and should do much more to collect, share and use information on scholarships. This should include data on applicants and recipients, how they were selected and the short- and long-term impacts on them as well as their families and communities. Then we can investigate how recipients’ employment prospects change on completion, how a choice to remain in Germany affects that, how this differs by gender and so on.

It might also prompt a rethink of the aid-eligibility criteria, which run against some of the latest empirical evidence. For instance, for tuition costs in a donor country to count as aid, the current DAC reporting directive requires “special measures against brain drain; and support for the reintegration of students into their home country.” And where students are granted the right to stay in Germany after completing their studies, their tuition costs are not counted as aid.

3. German education aid favours richer countries

Just over half of Germany’s education aid stays in Germany, channelled to local governments to cover tuition costs. But because each dollar that covers tuition is linked to a foreign student on a university course, the geographical allocation of German education aid is driven by the choices of millions of households in low- and middle-income countries.

Over the past five years, international students in Germany—from aid-eligible countries—have mostly come from North Africa, Latin America and South Asia. And middle income countries account for the majority of these, including large numbers from Brazil, China, Egypt, India, Iran, and Pakistan. Few students come from sub-Saharan Africa. Even among scholarship holders which Germany can target as it pleases, the value awarded to countries in sub-Saharan Africa is small.

The German government’s choice to use aid to fund tuition in German universities disadvantages women and girls. There is no doubt that the option to study fee-free enables more international educational migration. But as a consequence, Germany gives up most control over who benefits. And what we see is many more male students travelling to German universities. The overall gender parity index of those benefiting from aid-financed German tuition (0.7) is on par with the most recent gender parity index in Afghanistan’s primary schools (0.7). This is not the case in every country (see, e.g. China, Ukraine, Madagascar) but it’s considerably worse among most low and lower-middle income countries (see e.g. India, Pakistan, Sudan, Nigeria).

Figure 2.

Tip: Hover over a country to see a detailed breakdown or elect from aid for scholarships, aid for tuition in Germany and student gender

Source: OECD-DAC CRS data on aid payments from Germany to recipient countries for 2015-2019, inclusive. OECD data on international students studying in Germany. Note: USD figures are totals over the period 2015-19, in constant 2019 USD. Student counts are also totals over the period and should be interpreted as student-years spent studying in Germany. Differences in course type, duration and graduate destination lead to small deviations in the ratio between Germany’s imputed-tuition-based aid allocated to student-sending countries and the number of students from that country who are studying in Germany.

What this also means is that Germany’s allocation of education aid rises with the income level of the recipient (n.b. this is also true if we look at German aid across all sectors or if we look at German non-scholarship aid). The richer the recipient, the higher the share of German education aid, on average. With large shares going to geopolitically important middle-income countries including China, India, Turkey, Iran and Egypt. For all other donors combined, the share of education aid falls with country income level.

Figure 3. Germany’s education aid rises with the income level of the recipient

Source: OECD-DAC CRS data for all education aid received. World Development Indicators for GDP per capita. Note: shown for the five years 2015-2019, with selected countries highlighted.

4. Is Germany really a big supporter of multilateralism?

The German government and its people promote multilateralism. Yet at the same time, observers have challenged the country’s credibility in these statements, pointing to the tension between its convictions and its own selective compliance with them.

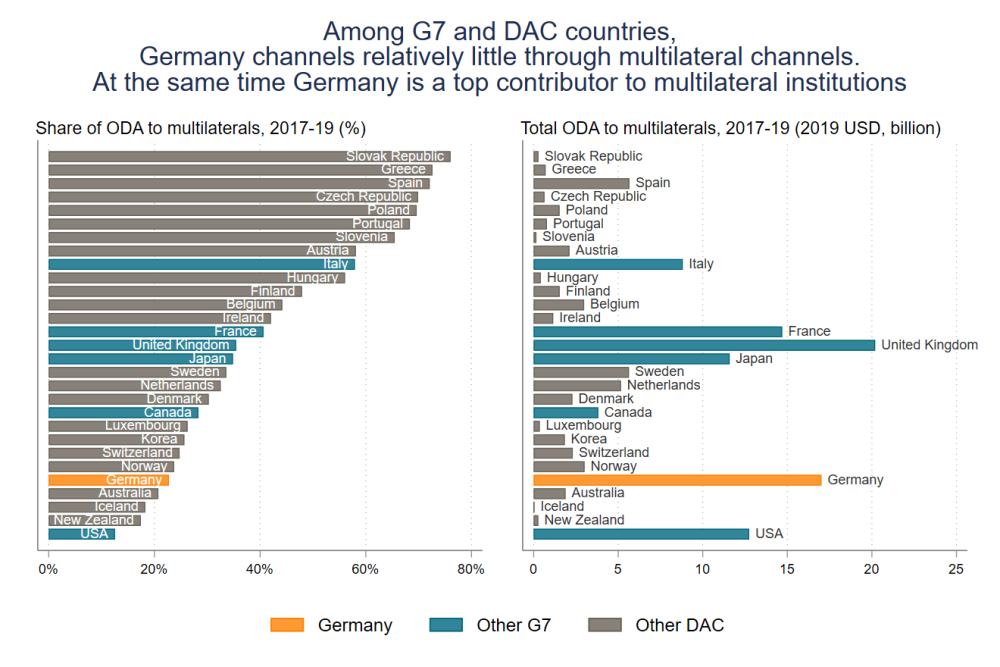

These criticisms are supported by information on aid flows. Latest data show that Germany ranks 6th of the G7 members and 25th of the 29 DAC members in terms of the proportion of aid it channels through multilaterals. Among G7 members, only the United States—which has shown disdain for multilateral settings—ranks lower.

Figure 4. Two interpretations of Germany’s funding for multilaterals

Source: OECD Development Finance Data. Table 14. “The flow and grant equivalent of financial resources by DAC members to developing countries and multilateral organisations”.

Donors also channel bilateral aid via multilateral institutions like UNICEF, to advance common goals. Even here, Germany sends a much smaller share of its aid via multilateral channels than other G7 members (Figure 4, left panel). Particularly in the education sector. Given that a donor is more likely to delegate to a multilateral that shares its preferences, or where it can influence their policies, Germany’s atypical preferences and limited political clout, may go some way to explaining these figures. Germany’s spending choices don’t seem to match its rhetoric.

But the low proportion of German aid being channelled through multilateral institutions obscures the fact that Germany is still the second largest multilateral donor in absolute terms (Figure 4, right panel). Thanks to its enormous aid budget Germany can both lead in multilateral contributions and retain the flexibility to spend via bilateral channels, with more control. And we may be witnessing a shift in Germany’s relationship with multilaterals too. In May 2021 the German cabinet adopted a Multilateralism White Paper, the main message of which is a push for a “more active and more effective multilateralism”.

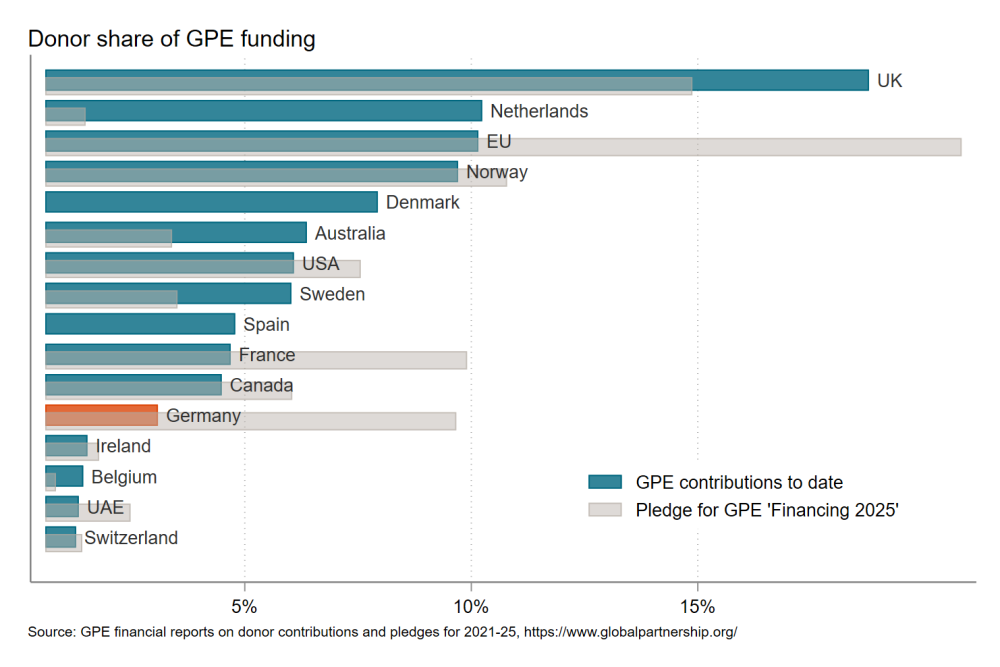

For the education sector the paper claims that, “Germany has the potential and a responsibility to play a greater role in shaping multilateral policy… through these organisations [Global Partnership for Education, Education Cannot Wait, UN agencies]”. It’s no surprise, then, that we see a major uplift in Germany’s pledge to the Global Partnership for Education for the Financing 2025 round. The contribution will see it move up from minor partner to 5th highest contributor. Similarly, Germany recently became the largest contributor to Education Cannot Wait.

Figure 5. Germany is moving from minor partner to top-five funder of the GPE

Source: GPE financial reports on donor contribution for 2021-2025, https://www.globalpartnership.org/

There is much to be learned from Germany’s unconventional approach to global education. And any assessment of the way that it gives aid has to be taken alongside the amount that it gives. Small proportions of enormous quantities are still very large.

But because Germany gives so much, there are several areas where more should be expected. Specifically, Germany needs to do much more to measure the causal impact of enormous outlay on higher education scholarships. In other words, is the use of ODA to fund foreign students in Germany a development best buy, a win for Germany’s higher education sector, or both? There are also indications that the way it spends aid (in particular the large part that goes to tuition in Germany) may not be doing enough to advance gender equality goals.

Germany’s support to global education is as much about the way that it approaches international cooperation as any educational priority. And we’re excited to see what a more active German multilateralism means for education policy as it takes on leadership of the G7 this year.

With thanks to Rachael Calleja and Therese Karger-Lerchl for helpful comments and Laura Moscoviz for research assistance.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.