Recommended

At the Global Education Summit this summer Prime Minister Boris Johnson asserted that investing into education was “the single best investment we can make in the future of humanity.” In line with this stance, the Foreign Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) is a staunch ally to the World Bank in its efforts to address learning poverty. But the UK is not putting its money where its mouth is and its recent expenditure reports show it has disproportionately cut aid to basic education.

Even before the UK government abolished its commitment to spend 0.7 percent of gross national income (GNI) on foreign aid, huge cuts were made to spending on aid. In July 2020, then-Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab announced that £2.9 billion would be cut from the 2020 aid budget, three months into the 2020 fiscal year. As our colleague Ranil Dissanayake predicted, cutting aid mid-year would always be messy.

But now that the UK government has published its actual spending for the 2020 fiscal year, we can see just how messy, particularly when it comes to education. What’s more, the cuts do not reflect the stated priorities of the UK government.

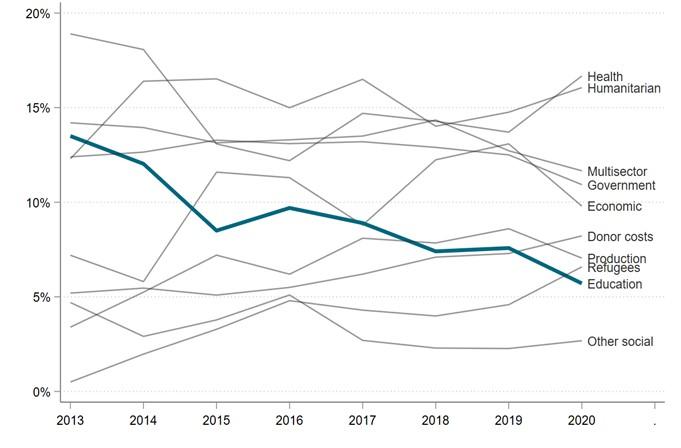

Education aid has decreased as a share of UK aid spending

Education has not fared well over the last several years. From a high of around 14 percent of UK aid spending in 2013 — and despite girls education being a priority for the government over the whole of this period —education spending constituted just 6 percent in 2020. Overall, aid for education remains much lower than aid allocated, for instance, to government and health sectors. Protecting health, humanitarian and refugee spend may well have been the right thing to do in the most recent years. But nonetheless the de-prioritisation of education is stark.

Figure 1. A steady decline in education prioritization

Source: Statistics on International Development, UK FCDO.

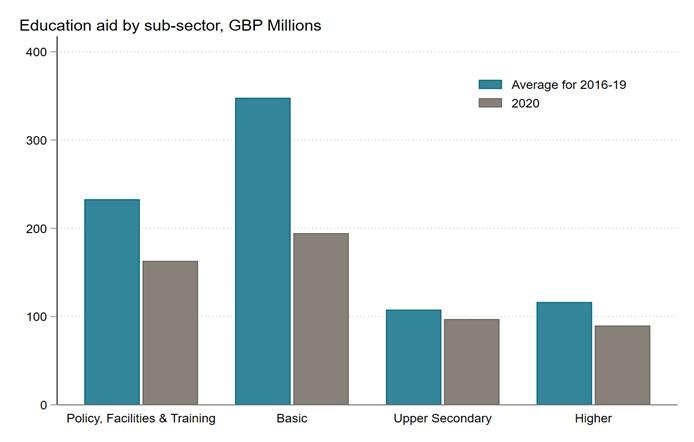

Basic education – primary education and foundational learning – took the greatest hit in the 2020 aid cuts

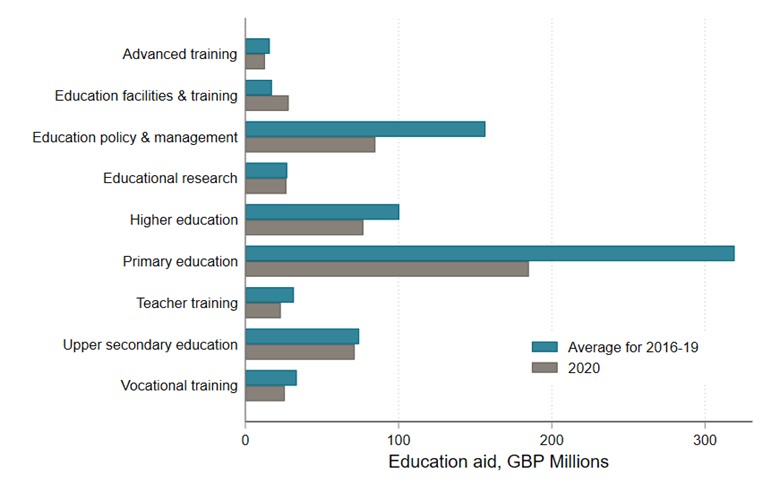

Given the FCDO’s claims on prioritising global education, it’s surprising that it is aid to basic education that suffered most during the first round of aid cuts. Between 2016 and 2019 basic education received around £350 million per year. This figure fell to £195 million in 2020. For upper secondary and higher levels, cuts have been far more modest.

Figure 2. Within the sector, the largest cuts are to basic education

Source: Statistics on International Development, UK FCDO. Note: all values are nominal, as reported by the UK Government.

As a consequence, the UK government spent pretty much the same amount on basic education as it did on upper secondary and higher education in 2020 (about 35 percent each). An argument could be made that this is a one-off, brought on by the need to make substantial cuts last year. If so, supporters of basic education might hope for a bit of a rebound in 2021.

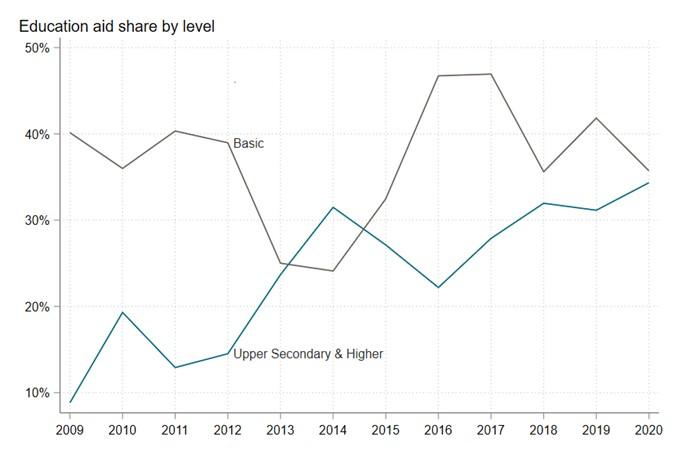

But it also fits into a decade-long trend towards more UK government spending at higher levels. This is not the “wrong” way to spend the budget, per se, but it is puzzling given the policy direction over that period.

Figure 3. Not a one-off, an increasing emphasis on higher education levels

Source: Statistics on International Development, UK FCDO.

Within basic education, aid to primary education was not protected

When we break it down further, the main share of the cut comes out of primary education. Education policy and management — the largest part of which is also used to support primary education — also loses out. On a more positive note, spending on education research has been protected.

Figure 4. Undercutting policy priorities

Source: Statistics on International Development, UK FCDO. Note: all values are nominal, as reported by the UK Government.

Coming back to what to protect when faced with the pressure to cut. At the highest level, aid to the health sector, humanitarian work and refugees appears to have been protected. This may have been the right thing to do in the current context.

Applying the same logic to education though, in the context of global school closures, learning losses in foundational skills, and inflated rates of repetition and dropout, doesn’t it follow that aid to the lower levels of schooling should be protected at all costs? That means primary, pre-primary and anything that supports this, including teacher training and facilities. But this is not what has happened. Instead, it is aid to basic education where the UK government cuts have been the deepest.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.