Future generations are (currently) blameless, our actions leave them in peril, but we can do something about it. All of this is utterly true of climate change, and it is why rich countries (that disproportionately pollute) should take the lead in paying for climate change mitigation and adaptation. But the same is true of global poverty. The world’s poorest people are poor through no fault of their own: overwhelmingly their poverty is a result of where they live. Our actions leave them in peril: not least, we forcibly prevent them from moving to places where they would be considerably better off. And we can do something about it. That is one reason why (at the very least) rich countries should take the lead in development finance. Even in the era of COVID-19-induced economic turmoil, the rich world can afford both of these obligations. But, instead, donors are trying to pretend they are meeting them through double-counting declining finance in a way that’s bad for both climate and development.

Some recent IMF estimates put the costs of limiting global warming to 2 degrees Celsius as low as 1 percent of global GNI. Even if rich countries were to deliver 0.7 percent of their GNI to ODA—more than doubling current aid volumes—and then add in the full 1 percent of global GNI for (low-end) climate mitigation costs, that would come to a little more than 2 percent of rich-country GNI. That’s equivalent to about a year’s economic growth.

New and additional?

Leaders in rich countries have repeatedly suggested that they know they can afford both obligations to the world’s poorest and to future generations: they regularly recommit to making progress towards the 0.7 percent aid target and they promise climate-friendly policies at home (which would take up the considerable majority of the IMF’s 1 percent) as well as “new and additional” financing to help developing countries bend the curve on global greenhouse gas emissions.

Of course, the more worldly among us might take it as given that when a president or prime minister stands up to announce they are providing billions of dollars in additional funding, what they mean is that they are providing billions of dollars in funding that was already there. But I’m still naive enough to be disappointed by the creative energy donor countries are putting into efforts designed to make them look like they’re doing more to tackle global challenges while they’re really doing less: reducing assistance and debasing the value of what they still provide.

Accounting tricks in aid…

Andrew Rogerson and Euan Ritchie note that the new rules on how debt counts as ODA “could potentially inflate the ODA numerator over the next several years with tens of billions of dollars of accounting entries, corresponding to few or no additional resources actually provided to developing countries.” And Rogerson and Ritchie report that in the UK, aid flows actually reaching developing countries (country programmable aid) increased at about the same rate over the long period 2005–2018. Much of the boost to the budget provided by the legislation mandating 0.7 percent of GNI to ODA in 2012 was spent in the UK, with country programmable aid around 0.19 percent of GNI in 2012 and around the same 0.19 percent of GNI in 2018—a trick accomplished by measures including reclassifying existing domestic research and development activities as ODA. One might hope that the announced cuts to UK ODA will at least be accompanied by a reversal of that process. My optimism burns like a spent wick in the rain.

But I’m still naive enough to be disappointed by the creative energy donor countries are putting into efforts designed to make them look like they’re doing more to tackle global challenges while they’re really doing less: reducing assistance and debasing the value of what they still provide.

…and climate finance

That’s before we even start on climate finance, where donors are trying to meet a significant part of their pledges through aid projects. Back to Rogerson and Ritchie: “The UK has also stated that climate finance will be on top of existing ODA commitments [but] the UK’s legal requirement to spend at least 0.7 percent of GNI on ODA has consistently been treated as a ceiling as well as a floor: the UK has hit 0.7 more or less exactly since 2013. As such, new climate mitigation initiatives introduced since then and counted as ODA are clearly not on top of existing ODA commitments.” Since 2013 the UK has committed around £6 billion in international climate finance and another £1 billion to the climate-mitigation-focused Ayrton Fund. As the climate commitment was first made in 2009 and the legal obligation (recently abandoned) to 0.7 percent was only made in 2012, you might want to argue that the funding is “additional over 2009.” But when UK aid is reduced to 0.5 percent of GNI this year, around where it was in 2009, that claim is going to look increasingly hollow.

That’s a sign donors are gaming climate finance, as well. Euan Ritchie and Atousa Tahmasebi report projects where disbursements in earlier years were recorded as having no climate mitigation focus, but disbursements in later years on the very same project claiming climate mitigation as a “significant focus.” Look at the UK again: budget support to Pakistan’s Khyber Pukhtunkhwa Province for education was suddenly classed as being significantly about mitigation half-way through the project.

As it happens, support for education might be a rather powerful tool to help developing countries deal with climate adaptation. Ten years ago, David Wheeler and colleagues noted that empowering women through improved education reduces household vulnerability to weather-related disasters. They suggested “neutralizing the impact of climate-induced extreme weather events by 2050” could be achieved by “educating an additional 18 to 23 million young women at a cost of $11 to $14 billion annually.” The broader point: development is the best way to reduce the harms that climate change will bring—harms that will be greatest in the world’s poorest countries.

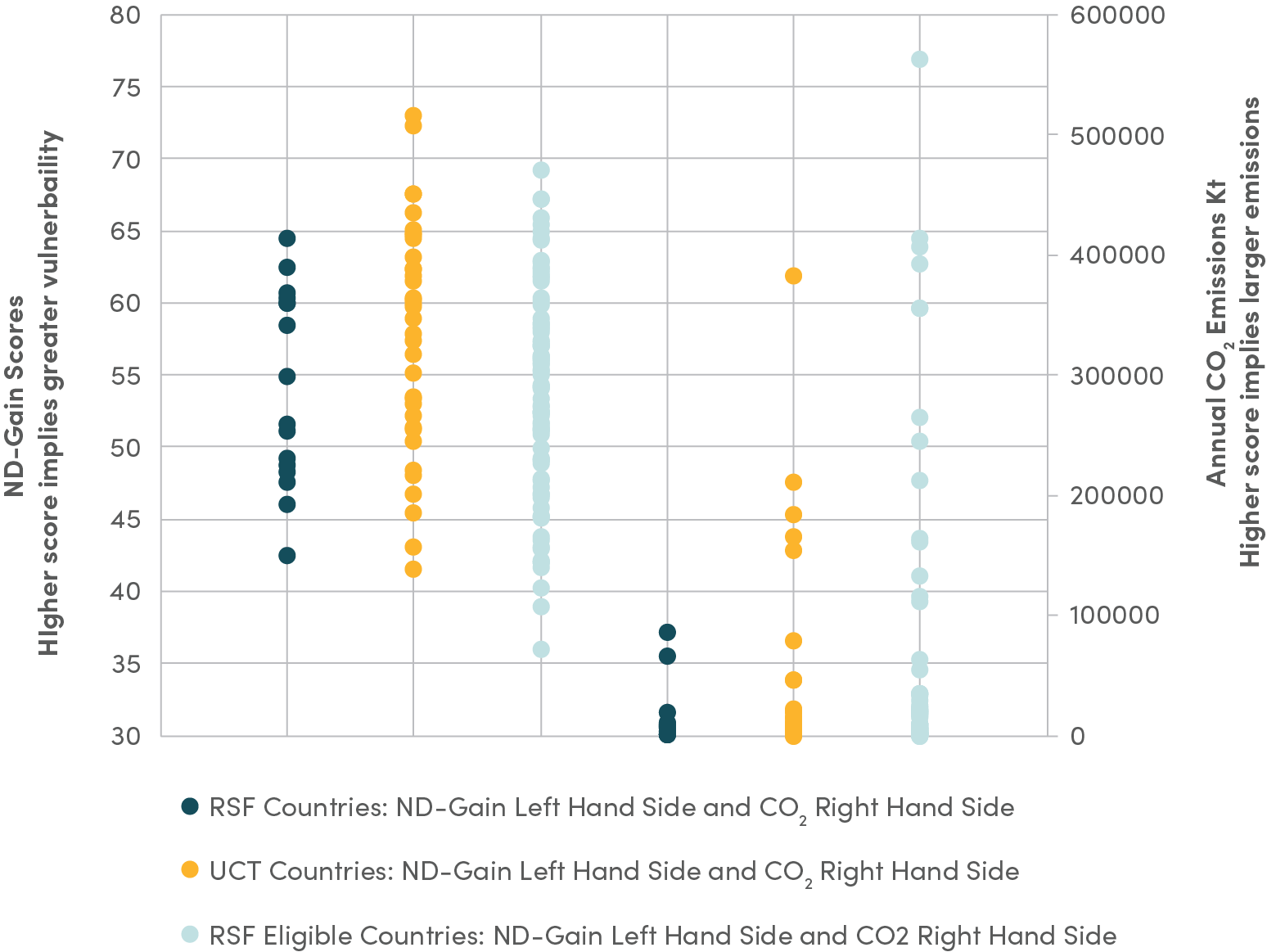

But there is a considerable disconnect between effective development aid and effective climate mitigation. Poor people aren’t major polluters: in fact, low energy consumption is one key reason they are poor. So you can’t solve climate change by focusing on the poorest people. But you can’t solve the most pressing development challenges by focusing anywhere else.

Synergies, or something less?

Donor attempts to double count aid and climate mitigation is going to lead to a lot of money spent on bad climate projects, or a lot spent on ineffective development projects, or quite possibly a lot on projects that are bad at both. Indeed, Ian Mitchell and Matt Juden note that some aid-financed climate projects are reducing emissions at the cost of $10 per tonne of CO2 equivalent averted, others cost closer to $1,000 per tonne. And while I’ve picked on the UK as a donor, other donors are behaving in a similar manner, if anything even worse.

The broader point: development is the best way to reduce the harms that climate change will bring—harms that will be greatest in the world’s poorest countries.

There are surely some projects in poor countries that can have significant local development impact and reduce greenhouse gas emissions as a side effect: perhaps forestry, improving agricultural yields, reducing local pollution, and (some) renewable energy projects. But robbing Peter in pretense of helping his grandson Paul is immoral and ineffective either as an overall aid strategy or a climate strategy.

The first step: Admit you have a problem

Existing ODA and additional finance for climate adaptation should be prioritized on the basis of effective development. New and additional climate finance for mitigation should be prioritized on the basis of its efficiency in reducing emissions. Leaders in rich countries are right to say they can afford to mitigate climate change and help the world’s poorest both at the same time. But if they aren’t going to deliver on that promise, the least they can do is admit it—and stop further damage to aid effectiveness in the meantime.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.