Recommended

Makhtar Diop, former minister of finance in Senegal and current vice president for infrastructure at the World Bank, has been tapped to be the next head of the International Finance Corporation, the World Bank Group’s private sector investment arm. This is welcome news: Diop’s experience and talents can help steer IFC towards greater development impact during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. And as with his predecessor, Philippe Le Houérou, Diop’s experience in the Bank should better integrate the private sector function with the institution’s broader development aims.

Diop’s experience in the Bank should better integrate the private sector function with the institution’s broader development aims.

In the last few months under the interim leadership of Stephanie von Friedeberg, the IFC has responded with speed and scale to help its existing clients through the COVID-19 crisis. The Corporation offered $8 billion in fast-track financial support in loans and trade finance to firms and banks that were already working with the IFC. Doubtless Diop’s first priority will be to further develop the Corporation’s work in responding to the global economic fallout of the pandemic.

But looking beyond the next few months, the managing director inherits a corporation that still faces two old, linked challenges that predate COVID-19: first, scale and focus, and second, chasing deals rather than chasing development. Dealing with these issues will be vital both to an effective response to the economic legacy of the pandemic and making sure the corporation delivers on its promise as a development institution.

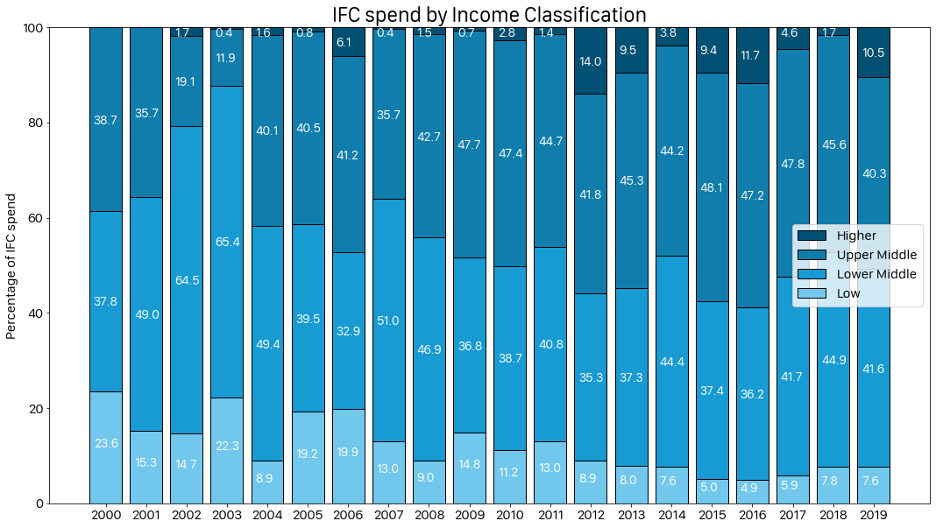

We’ve reported before that the IFC does most of its investing in larger and richer developing countries: India, China, Russia, Turkey, and Brazil. But these are also places where the Corporation is a bit player.

In Brazil, for example, the IFC’s summed investment from 2000 and 2019 amounts to $50 per capita, which pales in comparison to foreign direct investment per capita of $9,444 over that same period.

The countries where the IFC is large enough to make a real impact are also the countries where its support is most needed: smaller, poorer economies. And the IFC has promised to increase its commitments in the Bank’s IDA countries and fragile and conflict-affected states to 40 percent of its portfolio by 2030. But it is failing to deliver. Between 2000-2017, an average of 28.6 percent of IFC investments were in countries that were IDA status at the time of investment. In 2019, that declined to 24.1 percent.

The IFC’s failure to pivot reflects a culture that still favors deals over development impact.

The IFC’s failure to pivot reflects a culture that still favors deals over development impact: rather a big, simple investment in Brazil than a small, time-consuming project in Burundi. The “deals over development” culture also affects the impact of the projects the IFC does support. Take the energy sector: in his experience both as World Bank vice president for Africa and for infrastructure, Diop will have seen the harm done by unsolicited, non-competitive, and opaque power purchase agreements. He’ll know that the World Bank has consistently advised against that approach thanks to expensive failures in countries including Ghana, Tanzania, and Kenya. And yet unsolicited power deals accounted for an average of 37 percent of the megawatts the IFC co-financed between 2015 and 2019. And the IFC keeps on financing sole-sourced power projects, usually shrouded in secrecy, sometimes throwing in a subsidy on top. Given that, it isn’t surprising the available evidence suggests that the IFC is failing to convert its investments into development impact at the sectoral level.

Prioritizing the wants of client companies over the needs of poor people in poor countries also helps explain why the IFC simply ignored compliance failures when it disagreed with the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO), the independent accountability mechanism for IFC and MIGA which responds to complaints from project-affected communities.

Under Le Houérou, the organization made progress towards focusing on the poorest countries and taking development impact more seriously alongside competitive, capped, and transparent subsidy use. But the corporation still has a very long way to go to flip the culture to a priority on development.

The new managing director should prioritize the real clients of the IFC—not private companies but developing countries and the people who live in them.

Diop’s leadership should focus on ensuring far greater transparency and competition in the IFC’s approach and sticking to investments that meet World Bank approved standards in those areas—particularly where subsidies are involved. More broadly, the new managing director should prioritize the real clients of the IFC—not private companies but developing countries and the people who live in them. That would mean working with governments to help deliver private sector solutions that fit within development and industrial strategies and working with communities to ensure IFC financed projects sustain livelihoods. A vital first step will be implementing the findings of the independent external review of the IFC environmental and social accountability mechanisms. Makhtar Diop has a significant opportunity to deliver billions in finance for development in the countries that need it most. We hope he grasps it.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: GFDRR / World Bank Disaster Risk Management