Recommended

Some changes in leadership are more risky than others. The selection of the successor to Philippe Le Houérou, who leaves the IFC in October, is a prime example of a high-stakes decision. This decision has far reaching consequences for an institution that has to excel if the value of multilateral development bank finance for the private sector is to be credibly established. This is not a time for a choice governed by nationalist interest, geopolitics, or political horse-trading.

The IFC is an institution in transition, and Le Houérou has been at the center of that transition. His objective has been to put development at the center of its mission: in the way it selects investments and measures its impact, in the trade-offs it makes between impact and financial performance, and in the role it plays inside the World Bank Group. His shareholders have supported him, including by agreeing to a capital increase, which very much depended on his vision and credibility

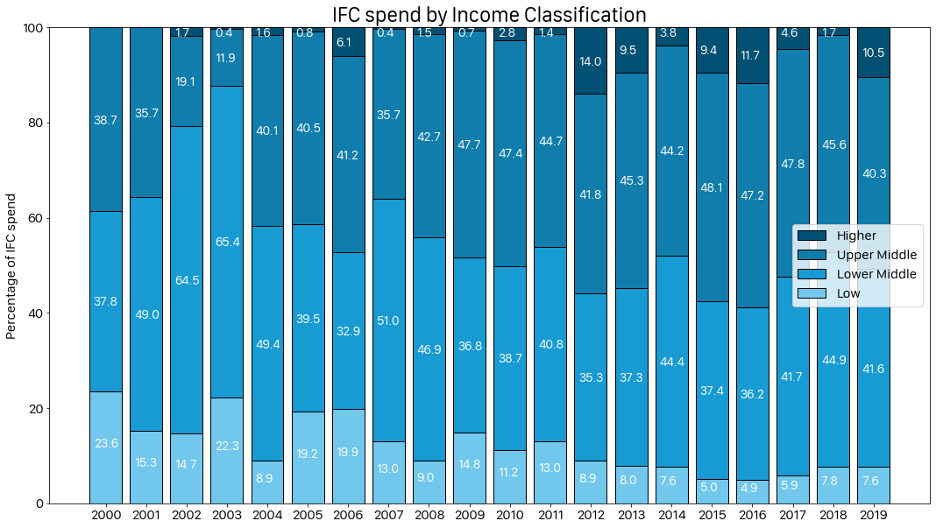

But while the ship has started to turn, it has a long way to go and it has not yet locked in the new course. As CGD colleagues have shown, the IFC’s volume of operations in poor countries is still much smaller than in upper middle-income countries, where investment opportunities are easier to find but where IFC’s “additionality” can be hard to demonstrate.

Boosting operations in poor and fragile countries to meet the targets set under the capital increase agreement requires a comprehensive strategy and fundamental change. Under the Le Houérou presidency, the IFC has pursued:

- change in its commercial banking culture to elevate the importance of development impact, including through staff performance incentives;

- change in the ex ante criteria for investment selection;

- a major new focus on “upstream development”, both investment climate changes and individual project development, to boost the supply of bankable investments;

- a clear rationale for deciding when finance should support the private sector vs. governments;

- a new enhanced voice for the IFC in shaping World Bank Group country and regional strategies to prioritize policies and institutions needed to support private sector development; and

- managers and staff who understand what is necessary for success in the poor parts of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

So this is an institution in the midst of rebuilding its foundation but not yet reaping most of the gains. The progress is therefore fragile and could stall or reverse if the wrong leader is selected. Add to that the risks and challenges of responding to the pandemic. It is critical this time, in contrast to its performance in the global financial crisis, that the IFC mount a strongly countercyclical response. All, including shareholders, profess to favor such a response, but let’s see how they react to inevitable balance sheet damage as IFC’s existing clients struggle and it becomes even harder to find projects with market returns in poor/fragile states. Navigating these treacherous straits will require a leader with clarity of vision, political skill, courage, and resolve, but also the personal credibility to convince staff that she has their back.

Navigating these treacherous straits will require a leader with clarity of vision, political skill, courage, and resolve, but also the personal credibility to convince staff that she has their back.

Beyond broad leadership skills, the head of IFC needs a wide-ranging set of abilities and experience hard to find in one individual:

- Deep empirical knowledge of private sector development;

- Understanding of the development finance institution (DFI) financial model;

- Understanding of commercial capital markets and investors, as well as impact investments and impact investors;

- Experience in engaging effectively with developing country governments on their policies and institutions;

- Experience in engaging effectively with developed world governments on their decisions about aid and DFI capital contributions;

- Experience in low-income, frontier, and fragile markets; and

- The ability to manage change in a large bureaucracy with offices around the world, and to attain its rightful place within the World Bank Group.

By all means there must be, and easily can be, women among the short list of serious candidates. No process that purports to be merit-based would exclude the excellent women development finance leaders that have emerged in both the public and private sectors, though some are perhaps less well known than their male peers.

Finally, there is the question of the IFC’s capital adequacy looming just over the horizon. Subscriptions and contributions under the capital increase agreement are already lagging those of the World Bank. One thing shareholders could do now to ease risks and pressures on the IFC is to accelerate their capital contributions. Realistically, though, down the road, if the IFC does respond at scale to the pandemic and fulfill expectations for the major portfolio shift and expansion in more difficult and riskier countries and operations, a case for an additional capital may well emerge. It will take a trusted, well-respected leader as well as a strong track record to make that case effectively: one more reason to choose carefully and wisely now.

The new CEO will be appointed by the IFC’s Executive Board on the recommendation of President Malpass. This is a time for President Malpass and the shareholders to put qualifications, experience, and demonstrated track record first. They cannot afford distractions. It will be hard enough to find someone with the exceptionally broad skill set needed. No less than the future of the IFC and its global impact at a time of urgent need depend on the right decision.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: World Bank Photo Collection/Flickr