Recommended

Key Recommendations

- Prioritize gender parity and broader inclusion in political appointments and personnel

- Appoint and empower strong leadership from within the White House and coordinated across relevant agencies

- Commit significant resources and energy to reduce gender gaps and other forms of inequality in low- and middle- income countries through development assistance, including through support to grassroots actors

- Harness a wide range of tools and policies to tackle persistent gaps—from foreign aid to trade, migration, and procurement policies

- Reassert US leadership on global gender equality and inclusion through multilateral fora

Increasingly, policymakers worldwide recognize gender equality—and broader inclusion based on race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, disability status, and other demographic characteristics—as a central plank of the global human rights agenda and a crucial development priority. But rhetoric is yet to be matched by the innovation, dedicated resources, and ambitious political leadership needed to drive meaningful progress. As the world’s largest bilateral donor, and an influential player in multilateral development fora, the United States has an important role to play in ensuring gender equality and broader inclusion are placed at the center of the global development agenda. This requires an intersectional approach: one that recognizes that all women and girls do not form a monolithic group sharing an identical lived experience, but rather face varying and intersecting forms of discrimination rooted in their location, income level, race, disability or migrant status, and other aspects of their identities.[1]

The Biden administration can restore the US government’s reputation as a global leader on gender equality—and take it to the next level through employing an intersectional lens. While the Trump administration emphasized the promotion of women’s economic empowerment, its overall approach to international development set the United States back when it comes to advancing global gender equality more broadly, as well as racial and economic equality at home and abroad. This is apparent in its unprecedented expansion of abortion-related restrictions under the Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance policy,[2] its elimination of funding to the United Nations Population Fund, its announced withdrawal from the World Health Organization,[3] and its promulgation and implementation of highly restrictive migration policies that perpetuate human rights abuses against vulnerable populations, including women and girls.[4]

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated economic recession, as well as racial justice movements across the United States, reinforce the need for a new approach to policymaking, especially where policies have entrenched and exacerbated systemic inequalities. Policymaking that is inclusive in its process and broadly beneficial in its outcomes is needed more than ever to help vulnerable populations weather the current crisis and protect against future ones.

Before COVID-19 hit, women’s labor force participation, access to finance, quality employment, pay, and advancement were all unequal to men’s. The pandemic and global recession are predicted to exacerbate these gaps.[5] Care work disproportionately falls on women and girls, and stay-at-home orders are likely to increase these burdens, play a role in increasing gender-based violence, and disrupt essential health services.[6] By pursuing an ambitious approach to promoting global and intersectional gender equality, the Biden administration can effectively address the COVID-19 crisis and the setbacks it has caused, as well as restore the United States’ credibility as a global leader.

To effectively champion global gender equality and inclusion, the US should increase its own workforce diversity

US government employees working on issues of international development do not yet reflect the backgrounds and perspectives of the US population they are meant to represent. According to a 2020 Government Accountability Office report focused on the US Agency for International Development (USAID), men are still over-represented among senior leaders at the agency.[7] In addition, the proportion of Black women employed by USAID declined between 2002 and 2018, in contrast to the increased hiring of both men and women of other racial backgrounds.[8]

Building on its campaign pledge for gender parity in national security appointments,[9] the Biden administration should set and meet specific targets ensuring that all political appointees, as well as the broader US government workforce, reflect the diversity of the US population in terms of gender, race, ethnicity, disability status, and other demographic characteristics. In setting clear targets and publishing data on progress to achieve them, the US government can improve diversity and inclusion within its own workforce, and in doing so enrich the perspectives brought to development decision-making, as well as broader domestic and foreign policy.

All US development assistance should address relevant forms of inequality

Applying a gender and inclusion lens to US foreign assistance does not require taking money away from US investments in global health, education, infrastructure, peace and security, or other critical areas of development. Instead, it means ensuring funding dedicated to these purposes is spent more effectively—that it is inclusive in its reach and benefits.

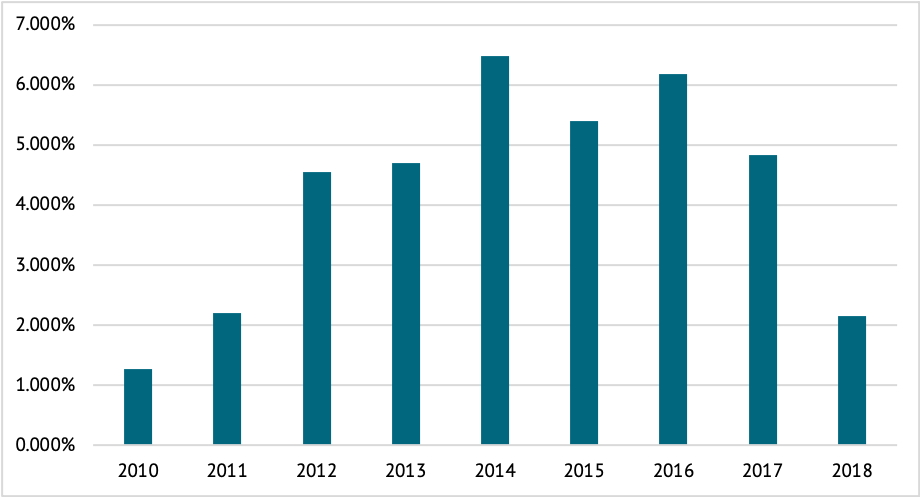

Currently, the United States allocates just 2 percent of its official development assistance (ODA) to projects that principally focus on promoting gender equality and women’s empowerment, and 16 percent to projects that significantly (i.e., as a secondary objective, among others) do so.[10]The percentage of aid principally focused on the promotion of gender equality steadily declined under the Trump administration (see figure 1), but the United States has long lagged behind its peers in gender-responsive foreign assistance.

Figure 1. Aid principally targeting gender equality, as percent of total ODA

Source: Aid projects targeting gender equality and women’s empowerment, OECD CRS.

How can the Biden administration improve this trend? Where development projects supported by USAID, the Millennium Challenge Corporation, the US International Development Finance Corporation, and other relevant agencies have already demonstrated equitable benefits—for example, helping to narrow gender gaps and improve outcomes in access to quality healthcare and education, skills training, agricultural inputs, employment and finance, safety and mobility, and other areas—such projects should be looked to as models of best practice to sustain, scale, and replicate. Where projects have been shown to have unequal benefits—for instance, an infrastructure project that overwhelmingly creates jobs for men and only supports men-owned businesses; or an agricultural project that overwhelmingly targets men as farmers—they should be reworked to ensure women and girls are included and benefit.

The same logic should apply regarding the extension of inclusive benefits towards those living with a disability, migrant and refugee populations, and other groups facing discrimination. By grounding all development spending in intersectional gender analysis, development agencies can ensure that the design, implementation, and evaluation of projects and initiatives will contribute to decreasing forms of inequality that hinder progress.[11]

Critical to this exercise is the collection and publication of project results data, including those documented through rigorous impact evaluations. Establishing an ex ante goal of ensuring that US development financing prioritizes gender equality and broader inclusion is a start, but only comprehensive, disaggregated results data can inform decision-making regarding which types of projects, across agencies and sectors, are having the intended impact. An interagency database housing information on all US development assistance—such as the Foreign Aid Explorer or foreignassistance.gov—should reflect this data and serve as a resource to inform decision-making.

Over time, this approach would enable all development assistance to ensure equitable benefits for women, girls, and other groups facing systemic discrimination. As reflected below, the United States has quite a lot of progress to make before even reaching the OECD donor average of aid targeted at promoting gender equality (35 percent), let alone the top performer position (currently held by Iceland, at 94 percent).

Figure 2. Total gender-focused aid as a percent of total ODA in 2018

Source: Aid projects targeting gender equality and women’s empowerment, OECD CRS.

When allocating more inclusive ODA, “to whom” matters as much as “how much”

In the present system, too little money is flowing directly to local actors best versed in communities’ specific priorities, needs, and constraints. In 2018, the United States allocated just $4.4 million to local women’s organizations in low- and middle-income countries.[12] In contrast, USAID alone allocated about $1.5 billion to a single private sector firm.[13] Whereas overall gender-focused aid stands at 18 percent of total US official development assistance, aid to women’s rights organizations is just 0.01 percent of total ODA, or 0.078 percent of gender-targeted ODA.

The Biden administration can lead the way in increasing investments in organizations that are locally rooted and operated by those who know their contexts best, many of whom are currently on the front lines providing critical support services in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and global recession.[14] One challenge (including to past efforts to promote local ownership, such as the Obama administration’s USAID Forward reform initiative, and the Trump administration’s New Partners Initiative) is current procurement and reporting systems, which are often inaccessible and/or overly burdensome to local civil society organizations, which are much smaller than international firms and NGOs and limited in financial resources. Procurement procedures and reporting requirements should be made proportional to organizations’ capacity, and technical assistance to seek bids and report on progress should be provided.

How can this be done? Models are available—including from Canada’s Equality Fund, the Netherlands’ Leading from the South Fund, and a variety of philanthropic foundations—through which donors can support preexisting women’s rights networks and funds (e.g., regional women’s development funds, the Global Fund for Women, Mama Cash, Prospera) as intermediaries that can facilitate connections to local organizations and lend assistance in navigating procurement and reporting requirements.[15]

This is one area that will require new funding to ensure success. For reference, the Netherlands’ Leading from the South Fund is a $46 million (€40 million) investment, which amounts to 0.8 percent of the Netherlands’ overall ODA for 2019.[16] Canada’s Equality Fund is a $288 million ($300 million CAD) investment, which amounts to about 5 percent of Canada’s overall ODA for 2019.[17]

If the US were to just match the Netherlands’ 0.8 percent allocation of ODA to local women’s organizations, this would mean allocating $270 million to local women’s organizations in low- and middle-income countries. If it were to match Canada’s, this figure would be $1.7 billion.

“Beyond aid” approaches can increase US ability to promote global gender equality and inclusion

Aid interventions in isolation are limited in their ability to tackle the systemic barriers that individuals in low- and middle-income countries face, and the United States has a range of additional foreign policy tools at its disposal that can contribute to this end.

This holistic approach to promoting gender equality and inclusion in low- and middle-income countries would be unprecedented. Previous administrations have established largely aid-focused initiatives tackling particular aspects of inequality in a piecemeal fashion: for example, the Trump administration launched the Women’s Global Development Prosperity Initiative (W-GDP), which uniquely focused on women’s economic empowerment. While an emphasis on areas such as providing access to finance for women entrepreneurs was welcome, the administration’s decision to cut support for other areas of women’s empowerment, including sexual and reproductive health and rights, undermined the initiative’s key objectives.[18]

The Obama administration also adopted something of a piecemeal approach, launching Let Girls Learn, for example, which focused attention on girls’ education. And while the Obama administration can be credited with looking to advance global gender equality more broadly through its installation of the first Ambassador-at-Large for Global Women’s Issues, the White House Council on Women and Girls, and the launch of its Global Strategy to Empower Adolescent Girls, it could have gone farther in prioritizing global gender equality in other areas. For instance, the administration missed an opportunity to integrate gender lens investing in OPIC’s portfolio or focus greater attention on promoting gender equality in the context of trade deals. Even in areas where the administration had strong political will, it sometimes lacked sufficient resources to realize its goals (see financing data above). The Biden administration has the opportunity to place intersectional gender equality front and center as a core priority—and do so in a way that harnesses all relevant levers of foreign policy.

For example, as reflected in the Women’s Economic Empowerment in Trade Act recently introduced by Senators Bob Casey (D-PA) and Catherine Cortez Masto (D-NV), US trade agreements can be harnessed to narrow global gender gaps, in part through giving trade preferences to countries that afford women and girls equal rights under the law—and thus arguably more equal access to the benefits of such agreements.

Migration is another powerful force for global development, with economic returns to migrants, the families they leave behind, and both destination and source countries. There is also significant evidence of social remittances from migration flows: migrants transmit attitudes from destination to sending countries in a manner that can improve norms and behaviors in areas from democratic accountability to gender equality.[19] By taking into account the greater barriers faced by women migrants (as well migrants coming from particular geographic locations, or racial, ethnic, or religious backgrounds, or education levels) when formulating migration policies, the Biden administration can harness the US migration system to better promote global gender equality and inclusion. For example, recognizing that the vast majority of workers entering the United States on H1-B visas are men,[20] the Biden administration can work to correct the currently gender-biased immigration system, and in doing so ensure that the US economy’s needs for migrant workers are met in an inclusive way.[21]

Finally, USAID, MCC, DFC, and other US agencies have the capacity to promote gender equality not only through the projects they implement but also through the firms and employees they hire. The Biden administration can build on existing (but small-scale) preference programs focused on veterans and people of color by ensuring that US agencies promote increased equality in procurement channels. For example, agencies can institute positive incentives for contractors that are women-owned, employ a diverse workforce, and/or promote equitable workplaces, as well as supporting outreach and technical assistance for entrepreneurs from diverse backgrounds to build capacity and increase their access to procurement channels.

Leadership and structures empowered to produce results will be required

The Biden campaign has already committed to create a new White House Council on Gender Equality, chaired by a senior member of the Executive Office of the President.[22] This new council should take an intersectional approach to its work, considering how gender intersects with other demographic characteristics to compound inequality and discrimination. The council should be given a clear mandate to coordinate across relevant agencies and with Congress, as well as sufficient resources to accomplish this goal. In this way, the Biden administration can ensure that its focus on promoting global gender equality and inclusion moves beyond political signaling to contribute to meaningful progress.

The US should improve its multilateral engagement on these issues

Building on its campaign pledge to push for the ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women, the Biden administration has the opportunity to restore the United States’ reputation as a strong multilateral collaborator on issues of equality and inclusion. The year 2021 offers a concrete platform for engagement and a reemergence of US leadership on global gender equality in particular: the “Generation Equality Forum,” which marks the 25th anniversary of the Fourth World Conference on Women and the resulting Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. President Biden or Vice President Harris could lead a delegation to the Forum and set the tone through making ambitious commitments in a global arena, encouraging others to follow suit.

A second area for multilateral engagement relates to improving development finance and results data focused on gender equality and broader inclusion. Currently, donor governments including the United States report their data to the OECD Development Assistance Committee, using its gender policy marker to signify that a particular project has a gender focus or component, or to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) using its gender marker.[23] These systems can be strengthened to ensure that all donors are employing the markers in a consistent manner, as well as through the integration of an intersectional lens—one that provides additional insights into how donor investments address other forms of inequality rooted in location, migrant, or disability status, and so on. The Biden administration can work in partnership with the OECD Gendernet and IATI teams, as well as other donor governments prioritizing the promotion of global gender equality and inclusion, to strengthen reporting systems and promote multilateral accountability on these issues.

Policy recommendations

The Biden administration has a unique opportunity to renew US global leadership in tackling systemic inequality. Reclaiming the leadership mantle in this area will require swift and assertive action—and is inseparable from our own domestic recovery and resurgence. Tackling gender inequality and other forms of discrimination holding the United States back at home cannot be separated from our outlook towards and approach to engaging with the rest of the world. A renewed and revitalized commitment to global gender equality and inclusion, reflected in the concrete actions proposed here, offers a way to make that ambitious vision a reality.

To deliver on this critical agenda, the Biden administration should:

- Set and pledge to fulfill gender parity and broader inclusion targets in appointments and personnel across government.

- Establish a White House Council on Gender Equality and Inclusion, with a dedicated budget and director to manage efforts across relevant agencies and engage with Congress.

- Commit that all US foreign assistance spending will integrate considerations of gender equality and inclusion, including through prioritizing support to local women’s organizations.

- Conduct a full review of the gender and broader inequality implications of US foreign policy, including trade, migration, and public procurement to identify areas where reform is needed.

- Increase and improve multilateral engagement on these issues, including through harnessing the 2021 Generation Equality Forum as an opportunity to reestablish US leadership on global gender equality and inclusion.

Additional reading

Charles Kenny and Megan O’Donnell, 2017. Using Trade Agreements to Support Women Workers. CGD Blog. Center for Global Development.

Charles Kenny and Megan O’Donnell, 2016. Why Increasing Female Migration from Gender-Unequal Countries is a Win for Everyone. CGD Note. Center for Global Development.

Megan O’Donnell, 2020. From Principles to Practice: Strengthening Accountability for Gender Equality in International Development. CGD Note. Center for Global Development.

Megan O’Donnell, Alex Farley-Kiwanuka, and Jamie Holton, 2020. Donor Financing for Gender Equality: Spending with Confusing Receipts. CGD Blog. Center for Global Development.

Lyric Thompson, Gayatri Patel, Gawain Kripke, and Megan O’Donnell, 2020. Toward a Feminist Foreign Policy in the United States. International Center for Research on Women.

With thanks to Shelby Bourgault for data calculations and visualizations.

[1] Intersectionality is defined as the “interconnected nature of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender as they apply to a given individual or group, regarded as creating overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage.” Crenshaw, Kimberle, "Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color," Stan. L. Rev. 43 (1990): 1241.

[2] Zara Ahmed, “The unprecedented expansion of the global gag rule,” Guttmacher Institute. April 28, 2020.

[3] Liz Ford and Nadia Khomami, “Trump administration halts money to UN population fund over abortion rules,” The Guardian. April 4, 2017; Steve Hollands and Michelle Nichols, “Trump cutting funding to WHO over virus,” Reuters. May 29, 2020.

[4] Michael Garcia Bochenek, “US: Family separation harming children, families,” Human Rights Watch. July 11, 2019.

[5] Kristalina Georgieva et al., 2020. The COVID-19 Gender Gap. IMF Blog. International Monetary Fund.

[6] Kate Power, 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the care burden on women and families, Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy; Amber Peterman and Megan O’Donnell, 2020. COVID-19 and Violence against Women and Children: A Second Research Round Up. CGD Blog. Center for Global Development.

[7] Government Accountability Office, 2020. USAID: Mixed Progress in Increasing Diversity, and Actions Needed to Consistently Meet EEO Requirements.

[8] Ibid.

[9] The Leadership Council for Women in National Security, Committing to Gender Parity in National Security Appointments.

[10] OECD DAC Creditor Reporting System (CRS), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=CRS1.

[11]Precedent for this recommendation lies in the Women’s Entrepreneurship and Economic Empowerment Act, which already requires that gender analysis inform USAID programming. This recommendation calls for the integration of an intersectional perspective, and a broadening of this mandate across all US development spending.

[12] OECD DAC Creditor Reporting System (CRS); OECD DAC, 2019. Aid in Support of Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment: Donor Charts.

[13] USAID, 2019. Foreign Aid Explorer: The official record of U.S. foreign aid, https://explorer.usaid.gov/.

[14] Amber Peterman and Megan O’Donnell, 2020.

[15] Megan O’Donnell, 2019. From Principles to Practice: Strengthening Accountability for Gender Equality in International Development. Center for Global Development.

[17] Equality Fund. “Equality Fund: Funding Feminist Futures,” https://equalityfund.ca/.

[18] Liz Ford and Nadia Khomami, 2017; Steve Hollands and Michelle Nichols, 2020.

[19] Charles Kenny and Megan O’Donnell, 2016. Why Increasing Female Migration from Gender-Unequal Countries is a Win for Everyone. CGD Blog. Center for Global Development.

[20] Ashley Parker, “Gender Bias Seen in Visas for Skilled Workers,” The New York Times. March 18, 2013 .

[21] Rebekah Smith and Megan O’Donnell, 2020. COVID-19 Pandemic Underscores Labor Shortages in Women-Dominated Professions. CGD Blog. Center for Global Development.

[22] “The Biden Agenda for Women,” https://joebiden.com/womens-agenda/.

[23] Megan O’Donnell, Alex Farley-Kiwanuka, and Jamie Holton, 2020. Donor Financing for Gender Equality: Spending with Confusing Receipts. CGD Blog. Center for Global Development.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.