Recommended

Nearly half of the global population of international migrants are women. COVID-19 is highlighting labor shortages in women-dominated professions and the consequences these shortages have for pandemic relief.

In key receiving countries in Europe, North America, and Asia, more women than men are migrants. Given their concentration in “essential” professions such as healthcare, childcare, domestic work, and food production and processing, women migrants’ contributions to host countries are more obvious than ever before, and are projected to become increasingly important (particularly in OECD countries) in the future.

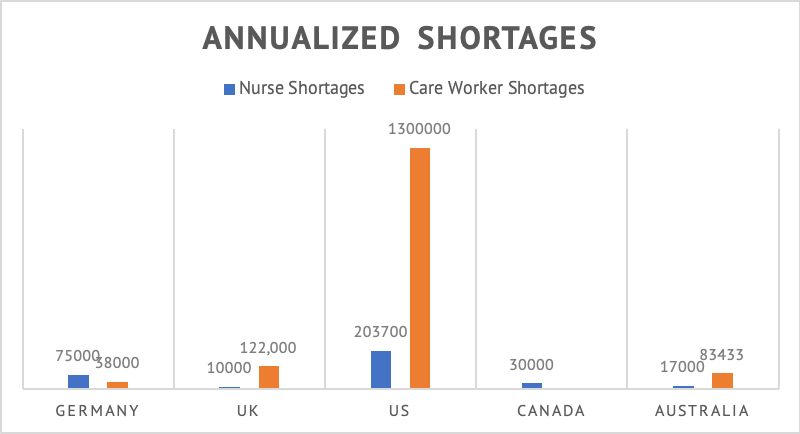

The numbers are stark. The nursing sector, for example, has long been a key employer for migrant women, and is likely to become even more so. As the figure below shows, on an annual basis, nursing shortages in some countries will be in the tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands. In the broader care work sector., the shortfall will be even starker; so much so ) that the president of the German Care Work Council has said “we will certainly have to look for carers abroad.” The vice president of policy of the US Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute went ever further, saying “it is impossible to imagine that the sector would survive without immigrants.”

Labor shortages on the COVID-19 frontlines

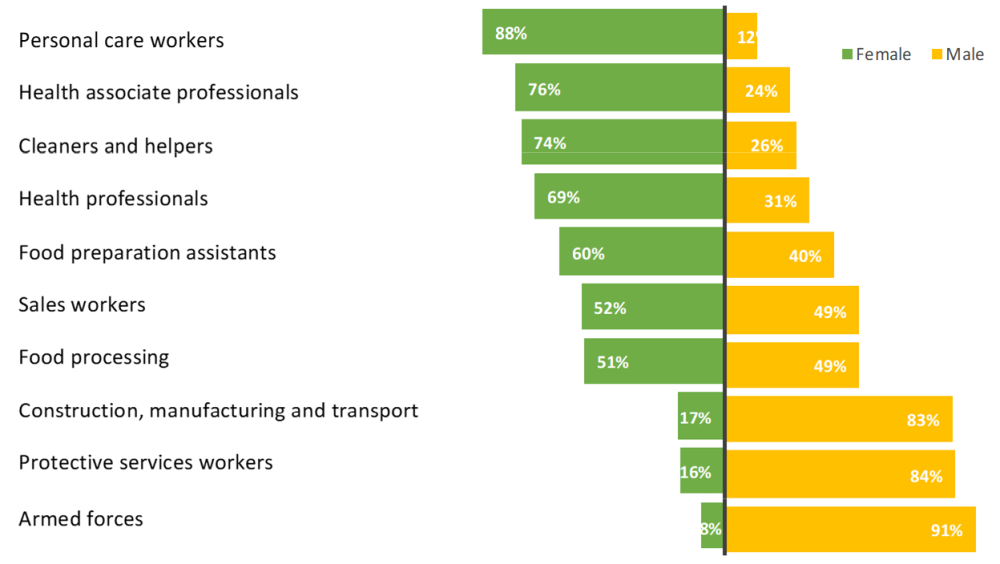

COVID-19 is highlighting the importance of these women-dominated sectors. In the US, one in three jobs held by a woman is designated “essential,” as work that ensures people are healthy, safe, and have access to services that address their basic needs, like food, transport, and childcare. Inequality is persistent, and women of color are more likely to hold these essential jobs than anyone else. In Germany, a stark 75 percent of all essential jobs are performed by women.

The World Bank chart below depicts the essential professions where women are leading the charge: care workers, nurses and health workers, cleaners and helpers.

Source: World Bank

These sectors already have labor shortages, made worse during the current crisis. Nursing shortages have already hampered countries’ ability to weather this outbreak. This issue also prevails in care for the elderly, as facilities have been epicenters of the virus, highlighting the importance of long-term residential care workers who are predominantly women, including high numbers of migrant women.

The COVID-19 era is giving us a glimpse of what will continue to happen if we don’t create better systems to address shortages. We can already see how damaging shortages are, not only during this crisis, but also for longer-term pandemic preparedness and countries’ overall social and economic well-being.

Building gender-responsive migration pathways

In realizing that massive shortages in essential women’s work sectors have already begun, we should begin to address them. A key element of preparedness is building better pathways to help migrant laborers enter sectors with shortages. Building these pathways must happen in a way that recognizes that migrants will be mostly women.

While women’s migration is becoming increasingly important, migration pathways have not become gender-responsive to address women’s specific needs and constraints. Migration policies that are framed as “gender neutral” disproportionately, and adversely, affect women in practice. Gender-responsive migration pathways would take into account women migrants’ unique needs, constraints, and opportunities, and the particular household impacts of women’s migration.

Women’s needs, constraints, and opportunities

1. Address constrained migration pathways in women-dominated sectors.

Restrictions imposed on migrants’ admissions into host countries can disproportionately block women’s migration, particularly when targeted sectors are not recognized as “skilled” professions (despite requiring training).

Nurses, care workers, and, in some cases, domestic workers, require specialized training and certification, but in many countries are not included under skill categories qualifying for visa status. For example, Switzerland has no official pathway for migrants to work as domestic workers, which doesn’t prevent women from joining the migrant workforce, but rather means a larger undocumented population.

Further, women-dominated sectors have lower pay and fewer labor regulations compared with other sectors, reflecting the fact that care work is undervalued. This imbalance impacts migration opportunities where wages are used as a proxy for skills. In the UK, for example, care workers fall under the wage threshold to be eligible for a visa in the points based system (as do nurses, though they have recently received exemption), and despite also being on the frontlines of COVID-19, visas have not been extended for care workers in the same way they have for doctors and nurses.

Better policies would start with all host countries conducting a gender analysis of current migration restrictions to determine the extent to which women’s migration is disproportionately constrained, and reforming their systems accordingly. Countries should consider removing migration restrictions based on wage and skill level, understanding that skill-based restrictions disproportionately bar women from migrating and may be based on flawed valuations of types of work. Such restrictions prevent host countries from addressing shortages in essential sectors (e.g., child and eldercare). A migration system based purely on labor market demand would be better for the economy while also resulting in better outcomes for women.

Where migration opportunities continue to be determined by skill level, policymakers can adapt the migration system to account for the different professional and life trajectories of women. For example, Denmark recognizes carers as skilled professionals, and Canada accounts for differences in life-courses between men and women, recognizing that because women disproportionately act as primary caregivers in their own households, they need allowances for part-time work and time out of the workforce.

2. Correct for poor recognition and use of skills.

Highly educated women migrants are more likely than men to end up in jobs that do not correspond to their education level and qualifications. For example, women employed as domestic workers or care workers often have higher levels of education than what their positions call for, but are unable to use their qualifications to get an appropriate job. This may be driven in part by a discriminatory preference for native workers in sectors where women are concentrated, which focus on relational work such as support, service, and caring labor. As a result, women are not only penalized by being trained in less-valued, lower-paid occupations, but further penalized as migrants by ending up in lower-skilled positions than their qualifications due to their ethnicity and migrant status.

Governments should invest in job placement programs for migrants to ensure that women are not disproportionately under-employed, and that labor market needs are met in a way that maximizes human capital potential. While such services play an important role for both men and women, they can be designed in a gender-responsive way to ensure equal benefits across genders. For example, employment services seeking to support women migrants may consider incorporating women as job counselors trained in the unique considerations of women migrants; conducting outreach to employers as well family members during the job search process to ensure family support for women’s work; and tying outcomes-payments to women’s job placements.

3. Address vulnerable working conditions.

In general, women are more likely to work in temporary, part-time, low-skilled jobs than men. Women migrants are overrepresented in sectors such as hospitality, domestic work, and care work, where workers are far more vulnerable as a result of being employed in a private or semi-private sphere.

The vulnerability of these workers has been even more evident in the COVID-19 era: in Lebanon, multiple cases have appeared where domestic workers are trapped in their abusive workplace, as they are not able to go to a shelter or to get on a plane home.

In response, support services should be instituted (or where present, scaled) to ensure that women migrants have recourse in the face of sexual harassment or abuse in their employment contexts, as well as, where possible, opportunities to engage in collective bargaining efforts to strengthen the quality of their labor conditions.

Support services for women migrants need to be designed in a way that accounts for these vulnerabilities, and in particular accounts for their constrained movement and communication. This means that each service should have multiple ways to contact them, ranging from private access points (i.e., hotlines and online submissions) to public access points (i.e., counselors or contact boxes in public spaces frequented by migrant domestic workers such as grocery stores, religious communities, consulates, remittance sites). Local governments should set up safe houses so that the worker can leave an unsafe situation without needing to leave the country, and migration systems should allow workers (particularly those in vulnerable employment) to change employers without leaving the country.

4. Expand and enforce migrant women’s rights

Forty percent of countries do not offer protection for domestic workers within national labor laws. Where they are included in labor laws, domestic workers are often offered fewer rights and protections than workers in other occupations. Even when women migrants have legal rights, they are less likely to be enforced than the rights of men migrants, as a result of women working in more isolated sectors and being less aware of their rights.

Policymakers should strengthen protections for domestic workers to align them with those for workers in other sectors, while adapting these protections to consider the unique risks of the sector. Migrants should have access to affordable legal services and be informed of their legal rights as part of their integration into host countries.

5. Consider and address Potential household/societal impacts (positive and negative)

Migration can be incredibly powerful for women, not only by offering far higher income than they could have made at home. Being able to migrate can help women increase their autonomy, reduce gender inequality, and strengthen their bargaining power within the home. In turn, women migrants can also influence social norms in their host countries and communities.

Other benefits research has shown that women migrants exhibit closer ties to family members at home than men, and that remittances from women migrants are more “reliable,” in that they change less with changes in income, and exhibit more altruistic patterns, since women’s remittances respond significantly to emergencies at home (whereas men’s do not).

However, there are also unique consequences of women’s migration to family structures, and these too should be considered in designing gender-responsive migration systems. While men may take on more unpaid care responsibilities when a female family member migrates, it is more common that this burden falls to other women in the household. Migration policies and programs today pay little attention to these wider impacts, in part because very little is known about them.

Policymakers should prioritize gender analyses of migration pathways to ensure they account for women’s needs and constraints, including a focus on implications for families. Gender-responsive migration systems should support families to account for the broader household effects, and to facilitate beneficial connections to home communities. These systems could include the provision of free or subsidized quality childcare services to ensure women migrants’ children are properly supported, as well as engagement programs that encourage men to absorb caregiving responsibilities typically designated to women.

What's good for women migrants and their families is ultimately good for health systems and other essential sectors in host countries, and economic stability and vitality in home countries. Whether in longer-term pandemic preparedness efforts, or in broader decision-making, gender-responsive migration pathways must be a priority.

Thanks to Helen Dempster for comments.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Dominic Chavez/World Bank