This note was originally published in draft form before Gavi’s March 2019 board retreat. You can view the original draft version here.

Introduction

Delivery of Gavi’s mandate—saving children’s lives through equitable access to vaccines—requires both access to vaccines and effective platforms to deliver vaccines to target populations. Broadly, investments to improve these platforms fall into two categories: upstream assistance for procurement and product selection, and downstream support for vaccine delivery.[1] Gavi has historically approached the second category under the auspices of health systems strengthening (HSS) and through technical assistance.

Gavi has steadily increased HSS commitments over time[2] and currently supports a range of activities under its Health System and Immunization Strengthening (HSIS) framework, launched in January 2017. The HSIS framework primarily encompasses HSS, vaccine introduction grants (VIGs), product and presentation switch grants, and operational support for campaigns (Ops), in addition to other broadly defined systems-related support.[3] The HSIS framework was amended in June 2018 to increase flexibility in countries’ HSS support ceilings[4] and, in November 2018, to support measles and rubella routine immunization activities.[5]

The HSS window began as flexible support with minimal monitoring (a “light touch”) and has over time adjusted the stated purpose of, and guidance for, HSS support.[6] Investments in HSS now target health system “bottlenecks” (cold chain, data systems) across four key strategic focus areas (SFAs) measured by five related key indicators, with signs of progress across most (see table 1).[7]

Despite these adjustments, Gavi’s approach to HSS support remains cumbersome for recipient countries and has not demonstrated an obvious or evident causal relationship between investments made and improved coverage rates or stronger health systems.[8] While it is difficult to measure and attribute outcomes at the system level, and although investments to address specific bottlenecks are important, they are small-scale efforts that are affordable within countries’ own budgets and may fail to address systemic incentives issues.

Many of the countries that will be eligible for Gavi support under its next five-year strategy (Gavi 5.0), moreover, have very weak health systems that constrain development and implementation of robust immunization programs.[9] Weak implementation and planning capacity coupled with a growing prevalence of conflicts and displacement further strain health systems and government budgets. Strengthening health systems is a task that presents complex, intertwined challenges, some of which may not fall within Gavi’s mandate or even control. The development of Gavi 5.0, therefore, presents an opportunity to reimagine how Gavi’s HSS support is defined and allocated while complementing efforts towards universal health coverage and strong primary health care.

In this note, we highlight the results of Gavi HSS evaluations, how Gavi has responded to identified challenges and limitations in the HSS proposal and implementation process, and what options are available to enhance the effectiveness of HSS support for Gavi’s core mandate. We also discuss the importance of 4G (Gavi, the Global Fund, the Global Financing Facility, and the World Bank Group) collaboration.

HSS Support in Practice: An Ever-Moving Target

The HSS window was formally launched in 2007, thanks in part to evidence from evaluations that indicated weak health systems adversely affected Gavi’s performance.[10] Gavi’s HSS window has evolved significantly since then, demonstrating both a responsiveness to the need for adjustments in scope and approach as well as an indication of the inherent difficulty in identifying appropriate and feasible mechanisms for strengthening health systems across a range of diverse contexts. Gavi’s focus on supply chain performance, data quality, access and demand, integrated service delivery, and engagement with civil society organizations in the 2016–2020 strategy has helped move the HSS window in the right direction towards more targeted, outcome-oriented support to countries (see table 1). It also positively reflects Gavi’s receptiveness to critiques raised in evaluations and a willingness to take recommendations on board.

Table 1. 2016–2020 Health systems strategic focus areas (SFAs) and key indicators

|

SFA

|

Data | Supply Chain | In-Country Leadership, Management, and Coordination of Immunization Programs | Demand Promotion and Community Engagement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Key Indicators

|

Data quality measured by the proportion of Gavi-supported countries with a less than 10 percentage point difference between different estimates of immunization coverage | Supply chain performance measured by the average score achieved by Gavi-supported countries that have completed WHO’s effective vaccine management assessment | Integrated health service delivery measured by the percentage of Gavi-supported countries meeting Gavi’s benchmark of coverage levels for four interventions—antenatal care and administration of neonatal tetanus, pentavalent and measles vaccines—within 10 percentage points of each other, and all above 70% | Civil society engagement measured by the percentage of Gavi-supported countries that meet Gavi’s benchmarks for civil society engagement in national immunization programs to improve coverage and equity | Coverage with a first dose of pentavalent vaccine and drop-out rate between the first and third dose |

|

2020 Targets[11]

|

53% (47%) | 72% (68%) | 42% (44%) | 63% (18%) | 90% PENTA1; 5% Drop-out (86%; 7pp) |

Source: Authors, based on Gavi website.

The 2016 and 2018 meta-reviews of evaluations of HSS support, however, as well as recent Independent Review Committee and Full Country Evaluation (FCE) reports, indicate that issues with Gavi’s design, implementation, and monitoring of HSS support have not been sufficiently addressed over time, and ongoing challenges continue to undermine the effectiveness of this window (see box 1).[12] The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation’s (IHME) 2016 FCE Annual Dissemination Report, for example, cited “complex, time-consuming, and poorly understood processes of applying for HSS support” as a key ongoing issue for all four FCE countries that adversely affect the outcome of HSS grants throughout the entirety of the application, approval, and implementation phases.[13]

Box 1. Recommendations from 2016 meta-review

- Gavi to critically consider key aspects of the scope and objectives of HSS support.

- Gavi to provide complete information and improve clarity on HSS window, requirements, and processes for countries.

- Gavi to consider the most appropriate delivery model for HSS support and whether a more “hands-on approach” may be required for some countries.

- Gavi to conduct a critical assessment of how best to circumvent implementation delays.

- Gavi to consider the appropriate monitoring of HSS grants.

- Where HSS funding is channeled through partners, greater clarity is required on processes.

- Gavi to proactively clarify and provide guidance on reprogramming and reallocation of funding.

Source: Meta-Review of Country Evaluations of Gavi’s Health System Strengthening Support

Since the publication of the first meta-review in 2016, Gavi has introduced a series of changes in its guidelines as well as mechanisms for HSS-related support (broadly defined) that attempt to address identified weaknesses (namely recommendations 2, 5, and 7 in Box 1). The introduction of the HSIS framework in 2017, for example, along with the Country Engagement Framework and Targeted Country Assistance under the Partner Engagement Framework, are intended to enable greater tailoring of support to individual country needs, greater stakeholder participation, and streamlining of application processes to overcome recurrent challenges identified in evaluations. Box 2 summarizes several key adjustments Gavi has made since 2016, which broadly reflect an attempt at clearer design and implementation guidelines for recipient countries relative to pre-2016 guidelines.

Although these changes reflect Gavi’s acknowledgement of the underlying challenges with the HSS window, issues remain with Gavi’s HSIS framework. The most recent meta-review, published in early 2019, renews several of the preceding meta-review’s findings, including the ubiquitous challenge of financial sustainability beyond Gavi support.[14] And although the new meta-review highlighted enhanced collaboration and engagement with stakeholders during the proposal process, it also identified a growing problem of “channeling funds through Alliance partners…[which] may undermine national ownership and oversight.”[15] None of the six countries’ HSS support evaluations analyzed in the last meta-review are able to document the impact of the investments made under the HSS window nor the modifications introduced since 2016 (the HSIS framework, PEF, and JA).[16] While this may simply be a result of these reforms occurring too late in the evaluation period to make a difference or be accounted for, the continued absence of information as well as the lag in the implementation of changes nevertheless signals that the process has not yet generated a measurable impact on health systems or vaccination coverage rates.

Challenges on the Horizon

HSS support remains poorly defined with health system “bottlenecks” difficult to pinpoint

A total of 56 countries currently have active HSS grants, of which 10 countries have been approved for HSS support through the new Country Engagement Framework process introduced in 2016.[17] A coherent articulation of what activities are supported by the HSS window, however, remains elusive, and on a fundamental level, it is unclear what HSS support is intended to achieve. Although health system “bottlenecks,” or principal barriers to achieving vaccine coverage and equity, are referenced as areas countries should prioritize in their proposals for Gavi support, bottlenecks are primarily and somewhat vaguely defined in terms of Gavi’s strategic focus areas as well as in terms of specific populations and geographies.[18] The 2016 FCE cross-country report recommended Gavi explore “concrete and user-friendly tools and processes that support evidence-informed assessments of immunization bottlenecks” to inform HSS design; it is unclear whether Gavi has made progress in this area since 2016, though it has been reported that the greater difficulty lies in developing appropriate solutions for the bottlenecks identified.[19] Notably, for many countries—including FCE countries—these procedural changes will have a limited impact on existing HSS grants; that leaves 46 countries, or 82 percent of countries with active HSS grants, that are not necessarily benefitting from Gavi’s reforms and that may be experiencing ongoing challenges in implementation and monitoring of HSS support.[20]

In practice, what Gavi supports under the HSS banner is difficult to pinpoint and varies significantly depending on when an HSS application was submitted and what countries identify as priorities (which, again, is influenced by Gavi’s guidance in effect for HSS support). Liberia, for example, applied for HSS and Cold Chain Equipment Optimization Platform (CCEOP) support in September 2016 using the new Program Support Rationale (PSR) with five clearly articulated strategic objectives in line with Gavi’s core strategic focus areas and HSS key indicators.[21] Each strategic objective identifies the health system bottlenecks it intends to address. India, meanwhile, submitted a proposal in April 2017 for HSS support that focuses on routine immunization strengthening through four implementing partners, UNDP, WHO, JSI, and UNICEF.[22]

Box 2. Key changes since 2016

- Introduction of Health System and Immunization Framework (HSIS)

- Introduction of Country Engagement Framework (CEF), or portfolio planning

- Introduction of Partners’ Engagement Framework (PEF), which includes Targeted Country Assistance (TCA)

- Transition to Joint Appraisals from Annual Progress Reports, an in-country annual review of implementation progress

- Addition of Grant Performance Frameworks (GPF) with standard and tailored indicators

- Streamlining of HSS, vaccine, and CCEOP support through introduction of Programme Support Rationale (PSR) template

- Introduction of Program Capacity Assessments (PCA), a financial assessment tool

On the other hand, Zimbabwe’s HSS support, approved in the 2016–2017 period, is referenced in Gavi’s Mid-Term Review report as an exemplar of better targeting support towards low-coverage subnational areas. There are no HSS proposal documents in Zimbabwe’s country hub for this period, however, making it difficult to ascertain the funding mechanism and core objectives for this support.[23] Indeed, four of the 10 countries that have used the CEF process in this period do not have the pertinent HSS support proposal documents on Gavi’s website as of March 2019, and four others are either primarily or exclusively for CCEOP support.[24]

Frequent changes to frameworks and implementation delays undermine the clarity and relevance of HSS support

Even as guidance has improved, the inherent complexity of efforts to strengthen health systems combined with poor planning and implementation capacity in-country presents a quandary for the relevance of Gavi’s HSS support as a whole.[25] In particular, the prevalence of reprogramming or reallocation of HSS funds—reported in 9 of the 14 evaluations in the 2016 meta-review—indicates that HSS grants do not maintain relevance over time. While priorities and needs may evolve significantly over the lifespan of an HSS grant (making flexibility in programming of funds important), applications for new HSS support under the Programme Support Rationale now require countries to take a three- to five-year view of Gavi support.[26] Requiring countries to take this long-term view while also knowing that implementation is likely to be delayed by a year or more creates potentially ex ante irrelevant programming. With some countries repurposing their HSS grants for cold chain equipment (CCEOP) and with technical assistance via Targeted Country Assistance[27] to complement Gavi’s HSS support and New Vaccine Support, it is evident that HSS support applies to challenges in routine immunization and vaccine introductions. The definition of HSS support, however, has been tweaked nearly annually, making it hard for countries to understand what the HSS window covers.[28]

Ongoing process-related issues, as well as gaps in communication regarding delayed timelines, also contribute to frequent disbursement and implementation delays. In Uganda, for example, the 2016 FCE Annual Dissemination Report projected that disbursement delays (and lack of clear communication about the delays) would result in temporary cessation of HSS-funded activities due to HSS funding gaps.[29] Gavi HSS support has also, in some instances, supplanted domestic financing for operational costs, meaning that disbursement delays can hinder service delivery. These frequent changes and lack of clear indicators of success also make it difficult to monitor the impact of HSS investments over time. For example, the supply chain performance and civil society engagement indicators’ 2020 targets were only developed at the end of 2018, with no 2015 baseline available for the civil society engagement indicator. And while the introduction of Grant Performance Frameworks and the Program Support Rationale template may eventually provide a clearer window into the impact of HSS investments, subnational indicators feature in less than half of the 56 countries’ active HSS grants.[30]

The under immunized and underserved will overwhelmingly reside in Gavi-eligible countries with weak health systems in the next strategic period

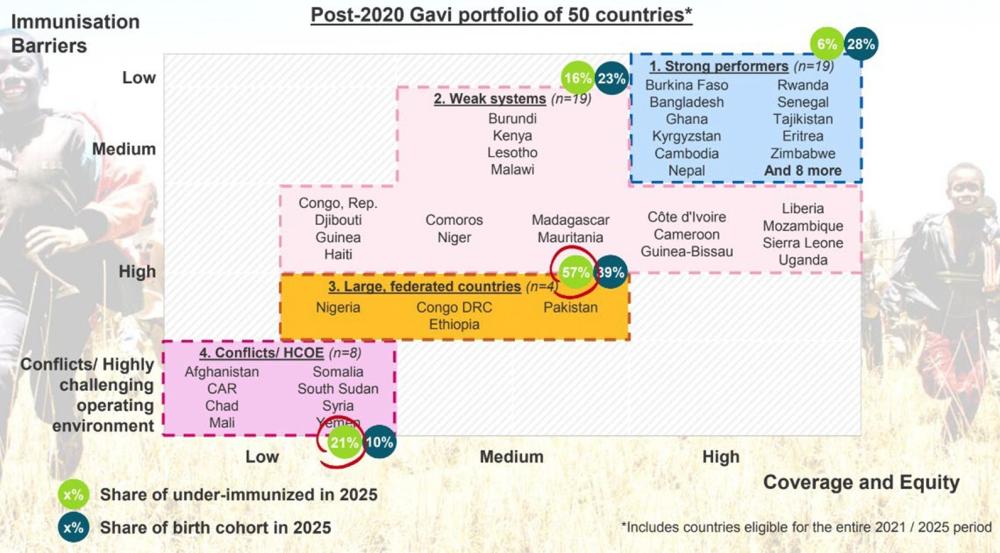

Among the 50 countries that remain Gavi-eligible during the next strategic period,[31] 19 are identified as having a weak health system (38 percent).[32] More than half of the under-immunized population (57 percent) and nearly 40 percent of the eligible birth cohort will live in just four countries in 2025, which have also been identified as having weak systems: Nigeria, DRC, Ethiopia, and Pakistan.[33] These weaknesses can but are not always reflected in vaccination rates -- Nigeria, a country with 197 million people, had an estimated 42 percent DTP3 coverage rate as of 2017, for example.[34] Pakistan, however, had an estimated DTP3 coverage rate of 75 percent in 2017 (though of course, at the provincial levels, variances may be more significant, as is the case with Ethiopia[35]).[36]

Figure 1. High concentration of under-immunized in countries with weak systems

Source: March 2019 Gavi Board Retreat, segmentation presentation.

As Gavi doubles down on its aim to reach the “fifth child,” it will have to do so in the context of increasingly fragile and weak governance settings. Country-level challenges affect all aspects of the health system; according to WHO, there is a global shortfall in excess of four million health workers and only 11 percent of African country governments adequately allocate resources for health in national budgets.[37]

The question therefore is how to address the challenge of under immunization in countries with weak health systems and where government may or may not be the best entity to deliver.

HSS support is small, slow to disburse, and channeled mainly to international partners

The majority of HSS grants are less than $5 million (per year),[38] representing a relatively small fraction of many countries’ health budgets. It is unclear whether these grants can be truly catalytic as envisioned. The stronger oversight mechanisms and guidance frameworks mentioned above have also resulted in disbursement delays due to country program management and capacity issues; HSS grants take, on average, more than 12 months to be disbursed after they are approved.[39] To prevent potential implementation delays, Gavi now channels two-thirds of HSS support through WHO and UNICEF and places partner staff in-country through Targeted Country Assistance, posing risks to country ownership and sustainability.[40] This reliance on external actors to oversee HSS support necessitates a rethink of the Gavi’s positioning of HSS support, including a more clearly articulated framework for collaboration with partners in-country.

Recommendations for Gavi’s Future Approach

1. Increase clarity, focus, and relevance by reframing Gavi investments as Vaccine Delivery Support

Creating an enabling environment for vaccine delivery is essential for achieving Gavi’s mission. Vaccination is a vertical program, however, and Gavi’s current HSIS framework should focus on vaccine delivery more explicitly, given that activities supported by the HSIS framework in practice constitute vaccine delivery and immunization systems. As an obvious starting point, Gavi 5.0 should reframe HSS support as “Vaccine Delivery Support” to better speak to the purpose of this window and eliminate the multiple and confusing windows and acronyms. Gavi’s current guidelines for requesting new support, published in February 2019, include a definition of HSS support closer to this reality, while also indicating that Gavi will work towards a “portfolio view” of all Gavi support in-country.[41] While this portfolio view is critical to ensure all of Gavi’s support makes sense from a 10,000-foot view and contributes to sustainability in programming and financing, the purpose and intended outcomes of HSS funding itself also need to be made more explicit and intentional from an institutional perspective.

In the next strategic period, Gavi should articulate a more clearly defined and coherent scope and approach to the HSS window that enables greater investment in sustainable vaccine delivery through this reframing. This should include revisiting both the problem definition underlying Gavi’s HSS window and the Alliance’s thinking around how to solve the problem so that the HSS window creates strong and clear incentives for vaccine delivery and coverage.

2. Develop and implement a clear set of criteria and framework for how Gavi makes allocation decisions under a health systems window

With total HSS support disbursements steadily increasing, Gavi should also consider developing a clearer and more transparent framework for how it makes allocation decisions for the total available funding under the HSIS umbrella and what kinds of activities HSS funding is intended to support. In the 2016–2020 strategic period, $1.3 billion has been allocated to HSS out of $2.1 billion total for HSIS programs (14 percent and 22 percent, respectively, of Gavi’s entire forecasted expenditure for this strategic period), yet it is difficult to discern what that money will in practice support given both the lack of insight into and lack of consistency in outcome and activity tracking across countries.[42]

To overcome the limited leverage and impact of existing funds, a possible solution could expand on performance-based funding in Gavi’s toolkit of modalities, looking to Salud Mesoamerica or the Nigeria Governor’s Immunization Leadership Challenge as examples.[43]

Gavi should also be explicit and transparent about how and when it decides to channel HSS support through partners and should develop a clear framework for when significant amounts of funding will be diverted from country governments.[44] This could also enhance clarity on timelines and implementation plans from the country perspective.

This increased clarity in what HSS support covers would ensure alignment with countries’ health budget allocations tailored to individual country needs and challenges at the subnational level, maintaining flexibility in approach while also introducing a greater degree of accountability (as Gavi has done with the Fragility Policy[45]). It would also assist with articulating the concrete problems HSS support is meant to solve while maintaining enough flexibility when course corrections are needed.

3. Develop a policy framework with the Global Fund and the Global Financing Facility to ensure the Vaccine Delivery Support framework aligns with their broader HSS programmatic and financial priorities

While a systems-level perspective is needed in Gavi’s approach to ensuring coordination and complementarity of investments across the global health ecosystem, the broad goal of health system strengthening is beyond the scope of Gavi’s core mandate. Enhanced collaboration among the biggest funders in global health—including the Global Fund and the World Bank’s Global Financing Facility—will be essential in addressing the complex challenges ahead, with coordinated approaches in different countries key to successful interventions.[46]

While the Gavi Board has identified the “HSS agenda” as a promising ingredient in reaching the under-immunized and achieving universal health coverage, it should also carefully weigh its unique value add against the total HSS pot.[47] Of the Global Fund’s overall support, for example, 27 percent goes towards “building resilient and sustainable systems for health,” with many overlapping priorities.[48]

Gavi 5.0 should pursue a more coordinated approach with other HSS donors to ensure complementarity of investments, looking to recent examples such as the 4G Initiative (of which Gavi is a part), potentially even specific HSS-related commitments as part of 4G. Gavi should also examine its sharp increase in funding for in-country staff, partner or otherwise, to ensure that its technical assistance does not supplant training and capacity building of local staff.[49] Gavi could do this by working with countries to develop more robust planning processes for eventual transitions (as recommended in the 2016 FCE Annual Dissemination Report).

For example, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative’s (GPEI) anticipated winding down of vaccine-preventable disease surveillance support (among all other forms of support) has potentially enormous implications for certain countries with increasing emerging disease threats. As part of Gavi’s involvement in the global health security agenda, it could work with partners to invest in surveillance systems, which HSS support does (in theory) fund already. As part of a menu of what HSS support can cover, and in line with what Gavi decides HSS support is intended to achieve, targeted investments in surveillance could bolster preparedness and response in some of the most vulnerable countries in the next strategic period.

4. Consider demand-side approaches to address constraints and drive coverage improvements

In a recent study of 15 countries transitioning from Gavi support, 92 percent reported vaccine hesitancy, indicating that this dangerous growing trend warrants attention in Gavi 5.0.[50] Although the study was limited to transitioning countries, vaccine hesitancy[51] and other demand-related issues are likely to loom large in the next strategic period, including potential opportunity costs that may be poorly understood and/or reflected in HSS proposal design. If immunization is to serve as a primary platform for achieving universal health coverage and primary health care aspirations, and if hard-won gains in coverage and equity are to be sustained, it will be imperative for issues on the demand side to be identified and addressed in designing Vaccine Delivery Support grants.

Recent evidence suggests that vaccination uptake-focused interventions, such as education campaigns, financial incentives, task-shifting, and laws, can have a sizable impact on immunization.[52] Gavi should work with country governments and other partners to scale up proven interventions to accelerate coverage rates and attain and sustain herd immunity. Gavi should also consider developing relevant indicators at the subnational level in partnership with countries that will help identify barriers to vaccination and potential context-appropriate behavioral interventions, among others.

Conclusion

The Gavi Board has acknowledged that a more tailored and country-specific approach is needed to deliver on Gavi’s mission of providing access to life-saving vaccines. The Board has also acknowledged that fiscal and programmatic priorities should be coordinated across mechanisms to better advance shared goals and to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. To better align with Gavi’s core mandate and to better reflect the activities it supports, Gavi 5.0 should rename and redefine the HSS window to more explicitly orient it around vaccine delivery, develop a more coordinated framework for engagement with other global health funders, and work with countries to understand and address demand-related barriers to vaccine delivery.

This note is part of a series on the future of Gavi. You can find the full list of notes here:

[1] This note will focus on the latter; for a discussion of procurement and market shaping issues, see the accompanying note in this series, “Gavi’s Role in Market Shaping and Procurement: Progress, Challenges, and Recommendations for an Evolving Approach.”

[2] HSS support was introduced in 2007, with US$200 million disbursed in 2007-8. The Board has approved $1.3 billion for HSS support in 2016–2020. Health Systems: Scaling Up,” Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance, accessed 18 March 2019, http://gotlife.gavi.org/data/health-systems-scaling-up/.

[3] “Health System and Immunisation Strengthening Support Framework,” Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance, accessed 18 March 2019, https://www.gavi.org/about/programme-policies/health-system-and-immunisation-strengthening-support-framework/.

[4] Specifically, “to increase an individual country’s allocation ceiling for HSS support by up to 25% beyond the total amount of the ceiling calculated based on the HSS Resource Allocation Formula.” Gavi Board Meeting Minutes, 6-7 June 2018, https://www.gavi.org/about/governance/gavi-board/minutes/2018/6-june/minutes/02j---consent-agenda---modifications-to-gavi-s-hsis-support-framework-and-gavi-s-fragility,-emergency-and-refugees-policy/.

[5] Specifically, “operational costs support for M/MR follow-up supplementary immunization activities (SIAs).” Gavi Board Meeting Minutes, 28-29 November 2018, https://www.gavi.org/about/governance/gavi-board/minutes/2018/28-nov/minutes/10g---consent-agenda---gavi-supported-measles-and-rubella-immunisation-activities---amendment-to-hsis-support-framework/.

[6] Gavi, “Health Systems: Scaling Up.”

[7] Systems strengthening is the second strategic goal in the 2016-2020 strategy. Strategic focus areas include supply chain, data quality and use, demand generation, and leadership, management, and coordination. “The Systems Goal,” Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance, accessed 18 March 2019, https://www.gavi.org/about/strategy/phase-iv-2016-20/systems-goal/.

[8] Gavi claims nine countries have transitioned from Gavi support after receiving HSS support (second graphic in this link: http://gotlife.gavi.org/data/health-systems-scaling-up/) without any substantiation of this implied direct link (or even specification of which countries).

[9] Many countries are anticipated to transition from Gavi funding by 2030, including India, Pakistan, Nigeria, and Bangladesh, which are among the largest recipients of Gavi support; Gavi’s portfolio by the end of this period will be composed of—on average—countries with weaker systems (Silverman, Rachel. “Projected Health Financing Transitions: Timeline and Magnitude.” Washington, DC: Center for Global Development, 2019). For a discussion of the impact of projected transitions, see accompanying note in this series, "New Gavi Modalities for a Changing World."

[10] Storeng, Katerini T. “The GAVI Alliance and the ‘Gates Approach’ to Health System Strengthening.” Global Public Health vol. 9,8 (2014): 865-79. http://dx/doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2014.940352.

[11] Parenthetical percentages indicate progress against these targets as reported by Gavi in November 2018. Gavi Board Meeting Minutes, 28-29 November 2018, https://www.gavi.org/about/governance/gavi-board/minutes/2018/28-nov/minutes/03---2016-2020-strategy---progress-challenges-and-risks/.

[12] The 2016 meta-review analyzes 14 evaluations of HSS support completed in 2013-2015 for HSS grants approved before 2012. It also notes that the Independent Review Committee and Full Country Evaluation reports completed more recently support findings of the meta-review, though Gavi’s newer interventions may not be fully reflected in these reports. “Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance: Meta-Review of Country Evaluations of Gavi’s Health System Strengthening Support.” Cambridge Economic Policy Associates Ltd, March 2016. https://www.gavi.org/results/evaluations/hss/health-system-strengthening-evaluations-2013-2015/. The updated meta-review published in 2019 analyzes six additional evaluations of HSS support completed in 2016-2017. “Update to the 2015 Meta-Review of Gavi HSS Evaluations.” Gavi Evaluation Team, 2018. https://www.gavi.org/library/gavi-documents/evaluations/gavi-hss-meta-review--update/.

[13] FCE countries include Bangladesh, Mozambique, Uganda, and Zambia. Gavi Full Country Evaluations team. “Gavi Full Country Evaluations: 2016 Annual Dissemination Report. Cross-Country Findings.” Seattle, WA: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2017. http://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/policy_report/2017/Gavi-FCE_Cross-Country-Report_2017.pdf..

[14] “Update to the 2015 Meta-Review of Gavi HSS Evaluations,” Gavi Evaluation Team.

[15] “Update to the 2015 Meta-Review of Gavi HSS Evaluations,” Gavi Evaluation Team.

[16] “Update to the 2015 Meta-Review of Gavi HSS Evaluations,” Gavi Evaluation Team.

[17] Many of these countries submitted applications before Gavi’s introduction of Country Engagement Frameworks and Program Support Rationales, making it somewhat difficult to understand how the rollout of changes impacted these 10 countries. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. “2016-2020 Mid-Term Review report.” November 2018. https://www.gavi.org/library/publications/gavi/gavi-2016-2020-mid-term-review-report/.

[18] “Application Guidelines: Gavi’s Support to Countries.” Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance, February 2019. https://www.gavi.org/library/gavi-documents/guidelines-and-forms/application-guidelines/.

[19] “Gavi Full Country Evaluations: 2016 Annual Dissemination Report,” IHME.

[20] “Gavi Full Country Evaluations: 2016 Annual Dissemination Report,” IHME.

[21] Liberia’s total HSS ceiling for the 2017-2021 period is $11.84 million. “Proposal for PSR (HSS & CCEOP) Support 2017: Liberia.” https://www.gavi.org/country/liberia/documents/proposals/proposal-for-psr-(hss---cceop)-support-2017--liberia/.

[22] India’s phase two of its HSS is for US$100 million. “Proposal for HSS Support 2017: India.” https://www.gavi.org/country/india/documents/proposals/proposal-for-hss-support-2017--india/.

[23] https://www.gavi.org/library/publications/gavi/gavi-2016-2020-mid-term-review-report/

[24] The 10 countries are: Comoros, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Haiti, India, Liberia, Malawi, Sierra Leone, Togo, and Zimbabwe. “Health Systems: Targeting the Underimmunised.” Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance, accessed 18 March 2019, http://gotlife.gavi.org/data/health-systems-targeting/.

[25] “2016 Full Country Evaluations – Alliance Management Response.” Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, 2016. https://www.gavi.org/library/gavi-documents/evaluations/fourth-annual-fce-report-(2016)---gavi-response/.

[26] “Apply for health system strengthening support.” Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, accessed 18 March 2019, https://www.gavi.org/support/process/apply/hss/.

[27] See accompanying note in the series, “Gavi From the Country Perspective: Assessing Key Challenges to Effective Partnership,” for a discussion of challenges with Targeted Country Assistance support.

[28] Indeed, Gavi guidelines as of February 2019 note the countries must “identify opportunities for integration and complementarity of HSS investments with vaccine introductions/campaign activities and other donor funding.” “Application Guidelines: Gavi’s Support to Countries.” Gavi.

[29] “Gavi Full Country Evaluations: 2016 Annual Dissemination Report,” IHME. Uganda is an unusual case: it was approved by Gavi in May 2017 for another round of HSS funding ($30 million committed and $13 million approved), yet no disbursements are reported in the period of 2016–2019 (and only $129,515 disbursed of $6 million committed in 2015). “Disbursements and commitments.” Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, accessed 18 March 2019. https://www.gavi.org/results/disbursements/. However, on Uganda’s country hub, $1.3 million of the $13 million approved for HSS 2 is reported by Gavi as being disbursed. “Uganda.” Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, accessed 18 March 2019. https://www.gavi.org/country/uganda/.

[30] “Health systems: measuring, learning & adapting.” Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, accessed 18 March 2019. http://gotlife.gavi.org/data/health-systems-measuring/.

[31] See “New Gavi Modalities for a Changing World" in this series for a discussion of the implications of Gavi’s eligibility policies and projected transitions.

[32] 27-29 March 2019 Gavi Board Retreat, segmentation presentation.

[33] 27-29 March 2019 Gavi Board Retreat, segmentation presentation; See Gavi Board Meeting Minutes, 28-29 November 2018, for earlier version of Figure 1, which identifies Nigeria, Congo DRC, Ethiopia, and Pakistan as having weak systems. https://www.gavi.org/about/governance/gavi-board/minutes/2018/28-nov/presentations/11---gavi-5-0-the-alliance-2021-2025-strategy/.

[34] “Nigeria: WHO and UNICEF estimates of immunization coverage: 2017 revision,” 7 July 2018. https://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/data/nga.pdf. Official country estimates are even bleaker at 33 percent for 2017.

[35] Glassman, Amanda and Liesl Schnabel. “Gavi Going Forward: Immunization for Every Child Everywhere?,” Center for Global Development, 7 February 2019. /blog/gavi-going-forward-immunization-every-child-everywhere.

[36] “Pakistan: WHO and UNICEF estimates of immunization coverage: 2017 revision,” 7 July 2018. https://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/data/pak.pdf.

[37] Adequate in this context is defined as 15% of domestic expenditure, per the 2001 Abuja Declaration. “Health systems: key expected results.” World Health Organization, accessed 18 March 2019. https://www.who.int/healthsystems/about/progress-challenges/en/.

[38] Gavi, “Health Systems: Scaling Up.”

[39] While these mechanisms are an important tool for preventing improper use of funds, the disbursement delays they create illustrate the potential trade-offs with which Gavi must grapple. “Health Systems: Challenges and Lessons Learned.” Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, accessed 18 March 2019. http://gotlife.gavi.org/data/health-systems-challenges/.

[40] “Approximately two-thirds of funding is now being channelled through partners to manage fiduciary risk.” “Health Systems: Challenges and Lessons Learned,” Gavi.

[41] HSS support as currently defined by Gavi’s guidelines aims to “facilitate sustainable improvements in immunization coverage and equity by targeting and tailoring investments to drive immunization outcomes,” which is an update to the definition included in guidelines published in February 2018. “How to Request New Gavi Support.” Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, February 2019. https://www.gavi.org/library/gavi-documents/guidelines-and-forms/how-to-request-new-gavi-support/.

[42] Gavi Board Meeting Minutes, 7-8 December 2016. https://www.gavi.org/about/governance/gavi-board/minutes/2016/7-dec/minutes/05---financial-forecast-and-programme-funding-envelopes/.

[43] See “New Gavi Modalities for a Changing World" in this series.

[44] Afghanistan’s March 2019 decision letter for HSS support, for example, includes the clause: “a proportion of the Annual Amount may be disbursed directly to an agreed implementing agency, such as WHO and UNICEF, rather than to the Country,” yet it is unclear what factors would trigger disbursement of funds directly to partner agencies and what proportion of funds would be affected. “Decision Letter, Afghanistan Health Systems Strengthening Programme.” Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. 19 March 2019. https://www.gavi.org/country/afghanistan/documents/dlpas/decision-letter-afghanistan-hss-2019/.

[45] “Fragility, Emergencies, and Refugees Policy.” Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, accessed 18 March 2019. https://www.gavi.org/about/programme-policies/fragility-emergencies-and-refugees-policy/.

[46] See the Global Action Plan for Health Lives and Wellbeing for All, a joint initiative of 12 global health organizations: https://www.who.int/sdg/global-action-plan/.

[47] Gavi Board Meeting Minutes, 28-29 December 2018. https://www.gavi.org/about/governance/gavi-board/minutes/2018/28-nov/presentations/11---gavi-5-0-the-alliance-2021-2025-strategy/.

[48] “Resilient & Sustainable Health Systems for Health.” The Global Fund, accessed 18 March 2019. https://www.theglobalfund.org/en/resilient-sustainable-systems-for-health/.

[49] “How We Work Together: Quick Start Guide for New Members of the Vaccine Alliance.” Geneva, Switzerland: Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance, 2018. https://www.gavi.org/library/publications/gavi/how-we-work-together/.

[50] Cernuschi, Tania, Stephanie Gaglione, and Fiammetta Bozzani. “Challenges to sustainable immunization systems in Gavi transitioning countries.” Vaccine vol. 36,45 (2018): 6858-6866. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.vaccine.2018.06.012.

[51] See accompanying note in this series, “Vaccine Introduction and Coverage in Gavi-Supported Countries 2015-2018: Implications for Gavi 5.0."

[52] Brenzel, Logan. “Can Investments in Health Systems Strategies Lead to Changes in Immunization Coverage?” Expert Review of Vaccines, 13:4, 561-572, 2014. DOI: 10.1586/14760584.2014.892832.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.