A broad array of international actors agrees that many developing countries desperately need to collect more tax revenue.

The IMF has proposed minimum corporate tax rates. The World Bank has lent out over $10 billion for 60 projects around the world from 2005 to 2015 with the explicit goal of increasing tax revenues. The G20 has highlighted the importance of increasing tax-to-GDP ratios to achieve the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. And even under the Trump administration, USAID has emphasized domestic resource mobilization—the preferred euphemism for tax in development circles—under its new motto of “a journey to self-reliance,” in which countries are to be gradually weaned off foreign aid.

But one part of the World Bank is pushing in the other direction.

Measuring the cost of taxes, while ignoring the revenue

The Doing Business report is the World Bank’s most popular publication. The index at the heart of the report is based on a range of questions about a hypothetical company with 60 employees: How much would it cost to register the business? How long would it take to get an electricity connection? Do businesses have to pay workers a minimum wage and overtime? (The Bank agreed to drop that one under pressure from the US.) And notably: are profits taxed? Answers are scored and aggregated, then used to rank countries—and many of those countries have responded.

For better or worse, the Doing Business rankings matter. Rwanda devoted a whole government agency to improving its ranking. India’s Narendra Modi made India’s rise from 142nd to 77th into a campaign talking point, and this past year World Bank President David Malpass launched the Doing Business report at Mohammed bin Salman’s “Davos in the Desert” to celebrate Saudi Arabia topping the list as the world’s leading reformer. As the Bank’s Independent Evaluation Group reported in 2017, “the tax payment aspects of the Doing Business indicators (payments, time, and total tax rate for a firm to comply with all tax regulations) generally guide the business tax work that often includes drafting and enacting tax laws.”

The methodology of the “paying taxes” component of the Doing Business ranks countries based on the total tax bill faced by a hypothetical firm—profit or corporate income tax, property taxes, health insurance mandatory pensions, and compensation schemes. The higher the bill, the lower the score.

The Director of Development Economics at the World Bank who oversees Doing Business embraces the implication of the rankings that less tax and smaller mandated pension and health payments are always a good thing. When asked about the tax indicators at a panel at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, DC in December 2019, Simeon Djankov replied:

“…in Mozambique, in Pakistan, in the vast variety of countries around the world, is it true that if they manage to raise more taxes, they would actually without any corruption and with great efficiency invest? No! They’re going to steal this money.”

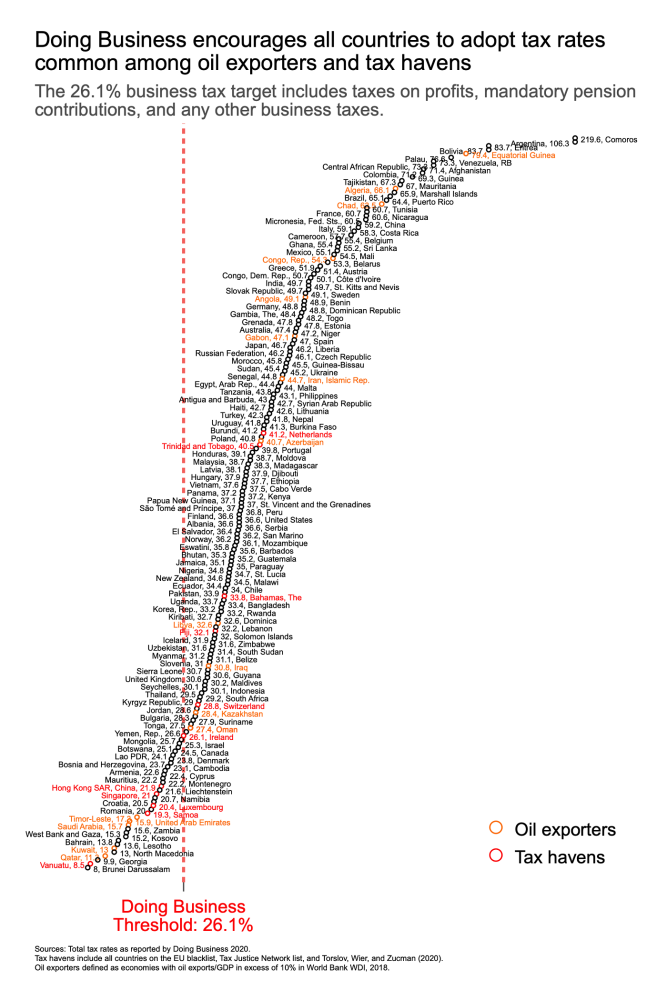

Doing Business originally set the universal ideal tax rate at zero (suggesting the idea that absolutely no country would invest any corporate taxes efficiently—not Pakistan, but also not Denmark, nor Germany, Costa Rica, or Chile). But after a report from the World Bank’s Independent Evaluation Group pointed out the problems with this approach, it raised the target tax rate from zero percent to anything below 26.1 percent of corporate profits. By the World Bank’s own description, “The threshold is not based on any economic theory of an “optimal tax rate” that minimizes distortions or maximizes efficiency in an economy’s overall tax system.” Instead, it’s set arbitrarily at the 15th percentile of all countries circa 2015.

Not many countries can afford tax rates below 26.1 percent of profits, and those that can are disproportionately oil exporters—like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Qatar—and tax havens—like Vanuatu and Samoa, which are on the EU’s blacklist for their lax tax enforcement.

Countries with functioning welfare states tend to tax much more. France comes in at 61 percent and Italy at 59 percent. Germany, Spain, and Sweden all score in the high forties. Even Switzerland and the UK, two very friendly jurisdictions from a business taxation point of view, still run afoul of the Doing Business 26.1 percent threshold. While recent tax cuts in the US brought corporate tax rates down from 35 percent to 21 percent, Doing Business still scores the US at 37 percent due to Social Security and Medicare contributions.

For over a decade, independent experts have been telling the World Bank to drop the tax rate from the Doing Business index

There are several obvious shortcomings with the Doing Business approach to scoring tax systems. The methodology does not consider the progressivity or regressivity of taxes, their incidence on firms or workers, or whether or not tax laws are enforced. Those are sins of omission. But the biggest problem with the index is a sin of commission: the absolute policy stance that lower tax rates are always better.

That absolutism contrasts with considerably more nuanced opinion from other parts of the institution and beyond. A recent blog from the IMF bemoaned that “[o]ver the past 30 years, corporate tax rates in all countries have fallen to very low levels,” for example. “This is a problem on several fronts,” suggests the IMF. It “undermines both tax revenue and faith in the fairness of the overall tax system [and] the current situation is especially harmful to low-income countries, depriving them of much-needed revenue to help them achieve higher economic growth, reduce poverty, and meet the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals.” Previously, the IMF has proposed regional agreements to keep corporate tax rates above a minimum threshold —exactly the reverse of the intent of the Doing Business cutoff.

There is a simple solution to this problem: drop the tax rate indicator.

That’s exactly what two independent reviews have asked the World Bank to do. In its 2008 review of the Doing Business program, the World Bank’s own Independent Evaluation Group concluded that “in order to improve the credibility and quality of the [Doing Business] rankings,” the Bank should “revise the paying taxes indicator to include only measures of administrative burden.”

Another independent panel led by former South African finance minister Trevor Manuel echoed this concern, and wondered why the Bank had failed to comply with the earlier recommendation to drop the tax rates from the calculation, since it “can be implemented at little cost.”

The Panel favours removing the tax rate indicator because, apart from the conceptual issues, a tax rate indicator is not a relevant measure of the ease of doing business in a country (although it does provide an imperfect indicator of the amount of tax paid by businesses).

It is time for the World Bank to follow this advice and drop the tax rate indicator. Perhaps the World Bank could even keep collecting the data on various tax rates around the world, and rather than dogmatically assuming taxation is automatically bad, release the disaggregated tax data to researchers to study the effects of alternative tax policies.

If it strives to be a source of trustworthy economic advice, the World Bank cannot let an isolated unit within the organization guide its tax policy based on a methodologically flawed index. The Bank’s own professional tax team is eager and capable to make more evidence-based, nuanced assessments of tax policy in the Bank’s client countries, and weigh the costs and benefits of generating domestic revenue. Let them get on with their work.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.