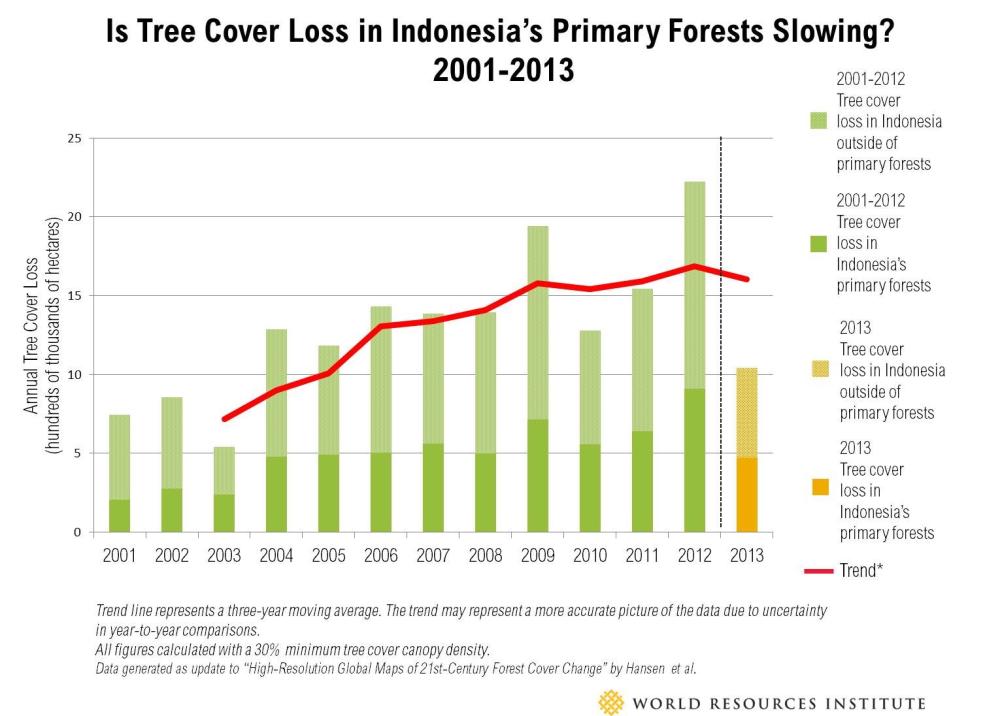

This week, World Resources Institute’s Global Forest Watch released new data showing that Indonesia’s deforestation rate declined significantly in 2013.[1] Based on satellite imagery analysis conducted by a team at the University of Maryland, Indonesia lost just over a million hectares of tree cover of in 2013, compared to double that the previous year.

Although the rate is still high, the decline is great news for the planet in terms of reduced climate emissions, as well as for the millions of Indonesians who rely on forest goods and services for their well-being.

What caused the decline? And what are the prospects that good news in 2013 will prove a robust long-term trend? At this point, we can only speculate on the answer to the first question – more on that below. But in the meantime, a new CGD Policy Paper sheds light on the second question. It suggests that the new administration of President Joko Widodo will have to move quickly to institutionalize the fight against deforestation initiated by his predecessor.

A Glass Half-Full

In November 2014, I accompanied CGD President Nancy Birdsall and Senior Fellow Bill Savedoff on a trip to Indonesia to understand the impacts of Norway’s pay-for-performance agreement with the Government of Indonesia to reduce climate emissions from deforestation. In our new paper, we report on the results of our inquiry.

In the agreement, concluded at the head-of-state level in 2010, Norway pledged up to $1 billion in return for results in reducing deforestation, the major source of Indonesia’s greenhouse-gas emissions. The agreement specified that during an initial phase, Indonesia would establish a new agency reporting to the president, and impose a moratorium on new forest licenses. Progress took longer than expected, but by the end of 2013 the Government of Indonesia had put these and other building blocks into place.

Perhaps as important, the agreement also raised the visibility and strengthened the hand of domestic constituencies for forest-related reforms, including those related to recognition of indigenous rights and combatting corruption. But the rate of deforestation stayed high and even increased through 2012, so there has been no payment for performance from Norwegian funds.

So what caused the decline in 2013?

WRI speculates that possible reasons for the decline in tree cover loss include:

a moratorium on new licenses for forest conversion, a significant decline in agricultural commodity prices (especially palm oil), corporate zero-deforestation commitments, and the fact that most accessible forests have been cleared already.

It’s important to note that only the first of those – the moratorium associated with the Norwegian agreement -- is a policy lever wielded by the government. A recent paper by my colleague Jonah Busch estimated that the moratorium’s expected impact would have been to decrease deforestation by 3.5% (and certainly not more than 10%) over the course of a decade compared to business-as-usual, because its scope was so narrow: it did not apply to forests that had already been logged, nor in areas already covered by licenses. And even if the moratorium had had a significant indirect chilling effect on forest clearing, presumably that would have shown up in the 2012 numbers.[2]

So unlike in the case of Brazil, which has implemented a range of policy measures to dramatically decrease deforestation over the course of a decade, government action is unlikely to have been the major cause of the 2013 decline in Indonesia.

Because attribution is tricky, we may never know the full explanation behind the 2013 decline, but my hunch is that the following factors probably contributed:

·In February 2013, Indonesia’s largest pulp and paper company, APP, succumbed to pressure from activists, and announced that it was withdrawing its bulldozers from the forest and would no longer source fiber from natural forests. A recent analysis identified the pulp and paper industry as the leading cause of deforestation within permitted concessions in Indonesia.

·In March 2013, the Norwegian pension fund (NBIM) disclosed in its 2012 Annual Report that it had divested from 23 palm oil companies with “unsustainable” business models. This signal that international investors were paying attention was undoubtedly noted by the industry.

·In June 2013, haze from Indonesian forest fires settled over Singapore. Satellite imagery – including maps produced by WRI -- drew the attention of both activists and the Singaporean government to role of commodity-producing firms in causing the fires. Singapore-based Wilmar International, the world’s largest trader in palm oil, came under particular pressure, and announced that it would cut ties with suppliers involved in illegal burning. In December, the company made an extraordinary commitment to rid deforestation from its supply chain, prompting a wave of similar commitments in 2014.

Sustaining the decrease

If voluntary private sector restraint and low commodity prices were indeed key factors in the 2013 decline, government initiative will be critical to ensure that progress is not reversed. Companies that have made commitments to deforestation-free supply chains -- including those that joined the Indonesian Palm Oil Pledge last September -- need complementary policy support if their efforts are to be successful in the long run, especially when commodity prices inevitably rise again.

Although the progress achieved to date under the agreement with Norway is real, it has been built on the fragile foundation of presidential decrees, and is thus dependent on continuing support from the new administration that had just assumed office at the time of our November visit. Indeed, the new ministerial-level agency created in 2013 was folded into the Ministry of Environment and Forestry in January, and its leadership and future direction remain uncertain.

So while news that the rate of forest clearing declined in 2013 is welcome, it is no reason for complacency. There are many ways the Jokowi administration could ensure that the single-year drop is the start of a downward trend rather than an anomaly. Here’s a short list:

- Renew the moratorium (which expires in May) and consider expanding its scope.

- Reform current regulations under which companies risk losing licensed forest areas that they fail to develop.

- Institutionalize the “One Map” process, designed to consolidate and publicly disclose information on forests, concessions, indigenous territories, and other spatial information across sectors.

- Support the Corruption Eradication Commission’s efforts to address forest-related crime, and expand the audits announced in January of palm oil licensees that clear peatlands.

- Rethink biofuel policies that would increase pressure on forests.

- Pilot domestic payment-for-performance, following India’s recently announced intention to include forest cover as a factor in revenue distribution to states.

Here’s hoping that the new government is successful in turning the 2013 drop-off into a long-term success, and that the international community is ready with a commensurate reward when they do.

[2] It’s also possible that the high rates of deforestation in 2011 and 2012 were amplified by the lagged impact of a frenzy of license-seeking just before the moratorium came into effect. Companies scrambled to secure land banks after the new policy was announced in May 2010, but before it was imposed in May 2011 (as described here). It would have taken time for those companies to move from the licensing to the land clearing stage, and by 2013 the surge in land clearing would have been dampened by low commodity prices.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.