More from the series

Blog Post

This blog is part two of a series on the findings of survey experiments with policymakers in 35 developing countries. Read part one in the series here.

A common concern of the education sector is that the global aid architecture is not fit for purpose: under-funded, lacking in leadership, fragmented and over-burdening of recipient governments. A review of multilateral aid organisations found UNESCO—the UN agency responsible for education—to have the weakest organisational strengths and weakest contribution to international development objectives of all multilateral agencies.

But too much of this debate happens among the global elites, aid donors and international organizations, without the voices of recipients of aid present. One notable exception is the AidData Listening to Leaders survey, from which we draw inspiration.

Last year we conducted a survey of over 900 senior officials (mostly Directors) in Ministries of Education or related government agencies, from 35 low- and middle-income countries. We surveyed them to get their opinions on the state of education aid, as well as their perceptions of and priorities for education more broadly. Here, we present four key findings about their views on global aid donors.

1. Fragmentation of aid is a concern for aid donors, not aid recipients

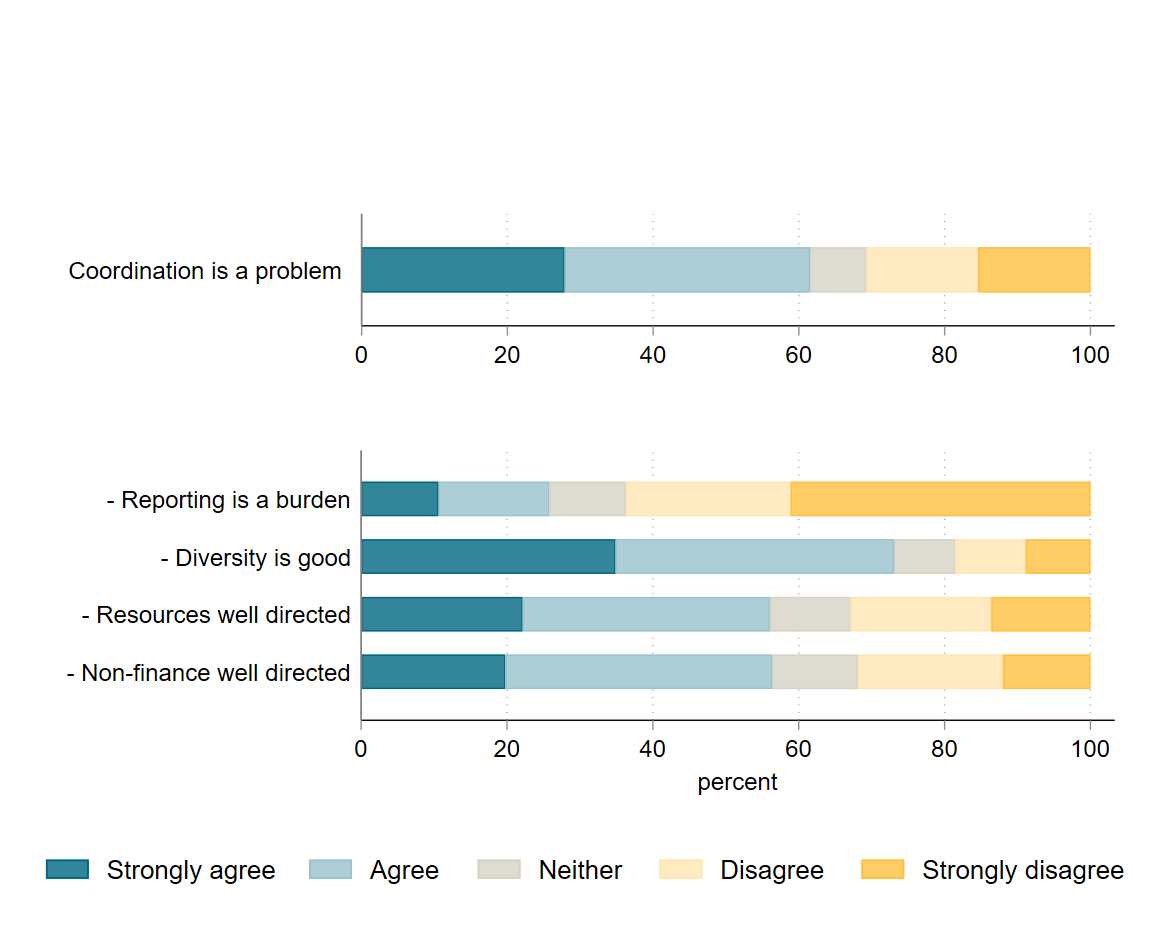

A major concern of aid experts is fragmentation, as discussed in the Paris/Accra/Busan aid effectiveness agenda. Too many donors running uncoordinated projects could lead to duplication or overlap in effort, and neglect in other areas. We find that officials are not so concerned about this. Whilst the majority agree with the statement that coordination is a problem, they are much less concerned when we move away from the abstract concept of coordination and dig into specifics (figure 1a).

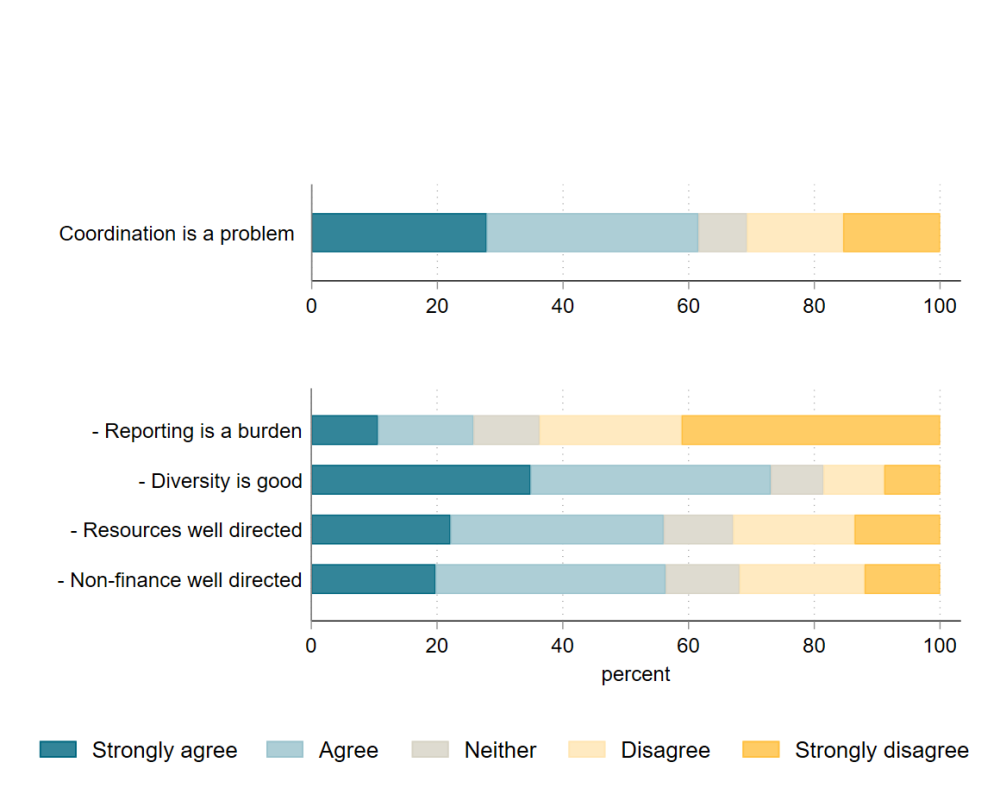

Most disagree that reporting to development partners is a burden, while a majority think that aid resources, both financial and non-financial, are well directed. And a strong majority agree that having a diverse range of development partners is actually a good thing. In some countries, where there are only one or two major donors working in education, governments can have little influence over their investments. With more donors around, governments have a better shot of a constructive dialogue with at least some of them. Only a few respondents said that they spend too much time with any specific donor (figure 1b).

These are all signs that coordination, though sometimes challenging, is in fact working.

2. Aid recipients value technical advisors at about $8 million each

Beyond money, an important function of international donors is to provide good advice to developing country partners. In fact a review of World Bank engagement has found that non-lending instruments (advice) can be more influential than lending instruments (money). This is particularly important for the many countries where domestic finance for social sectors dramatically outweighs donor money.

Donors spend large sums on advice and technical assistance for partner governments.he World Bank alone spends around $200 million per year on providing advice to developing countries, for instance. Total spend on technical assistance from Development Assistance Committee (DAC) donors makes up 6 percent of all bilateral aid, or around $4 billion per year (OECD, 2017). It’s challenging to measure the impact of technical advisers, but we were able to measure the financial value that officials place on them.

In a series of discrete choice experiments—designed to mitigate social desirability bias—we asked officials to choose between bundles of projects, with different education topics and varying amounts of funding and technical assistance. Using the 4,500 choices they made, we were able to calculate that the inclusion of a technical advisor in a project increased the chance of an official choosing that bundle by more than 10 percent. We can also infer the value of that single technical adviser at about $8 million. However, officials perceive that technical advisers have diminishing returns: the inclusion of two technical advisers is worth less than one. Perhaps policymakers don’t want to have to adjudicate between two different sources of advice (figure 2a).

Figure 2a. Officials are more than 10 percent more likely to choose a project if it includes a technical adviser

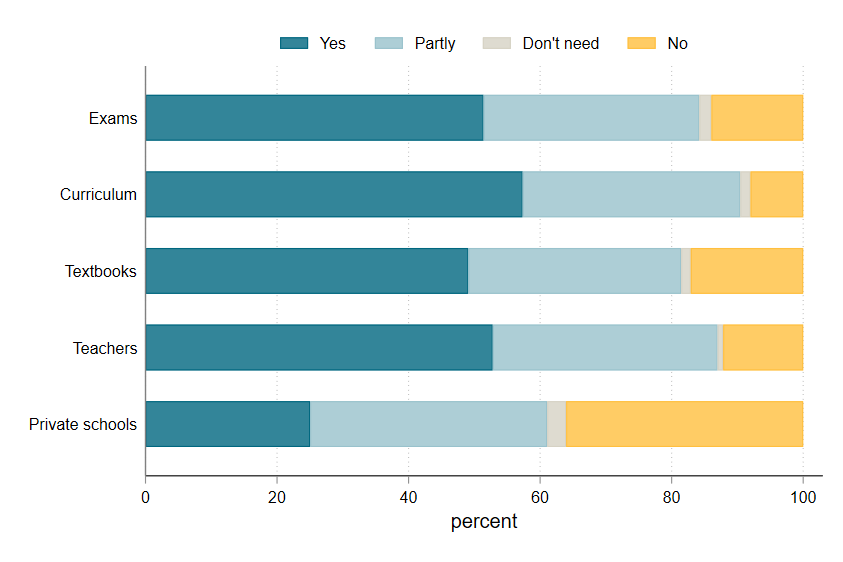

Alongside placing a high monetary value in it, we find that generally officials are content with the advice that they get from donors. This is true of all five policy areas we ask about—particularly on exams, curriculum, textbooks, and teachers (figure 2b). A sizable minority, though, are not content with advice from donors on private schools. We aren’t able to say whether this is due to the quality or (lack of?) quantity of advice, but it is present both in countries with small and large shares of children in private schools.

3. Keep writing your education policy reports—someone, somewhere, may be reading them

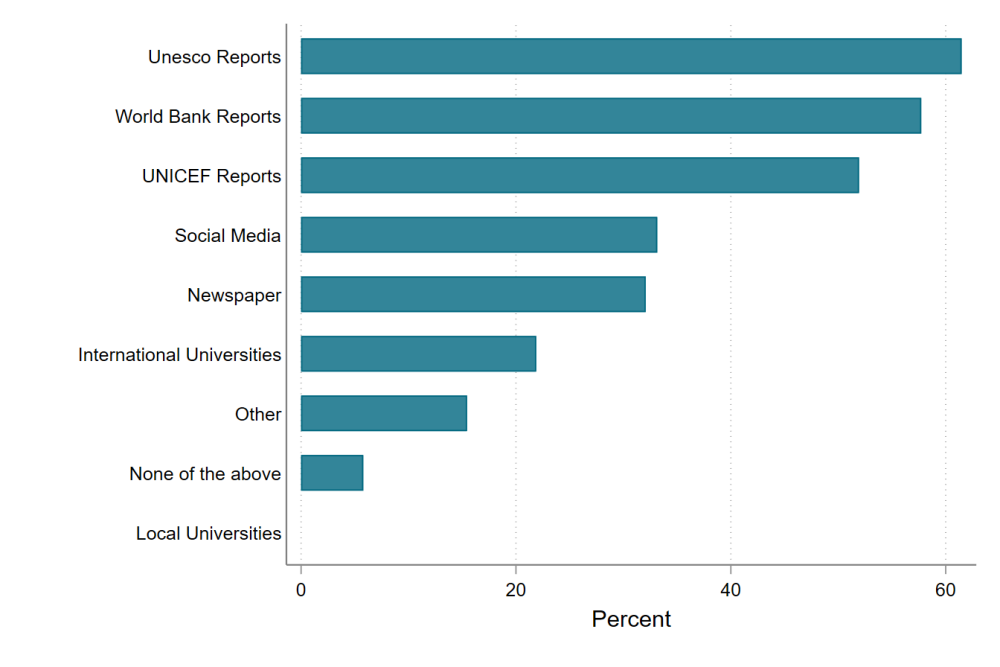

A 2014 report found that 31 percent of World Bank policy reports are never downloaded. This matters as a large share of spending goes on knowledge products. Our findings are more positive and will have report-writers in the big education agencies breath a sigh of relief. The majority of officials in our sample do read reports by all of the major international organisations in education—UNESCO, World Bank and UNICEF. They are much less likely to have looked to universities, either local or international, for ideas on education policy (figure 3).

Figure 3. Aid recipients (say they) do read UNESCO and World Bank reports

Note: Officials were asked “which of these sources have you looked at in the last 12 months for ideas on education policy?

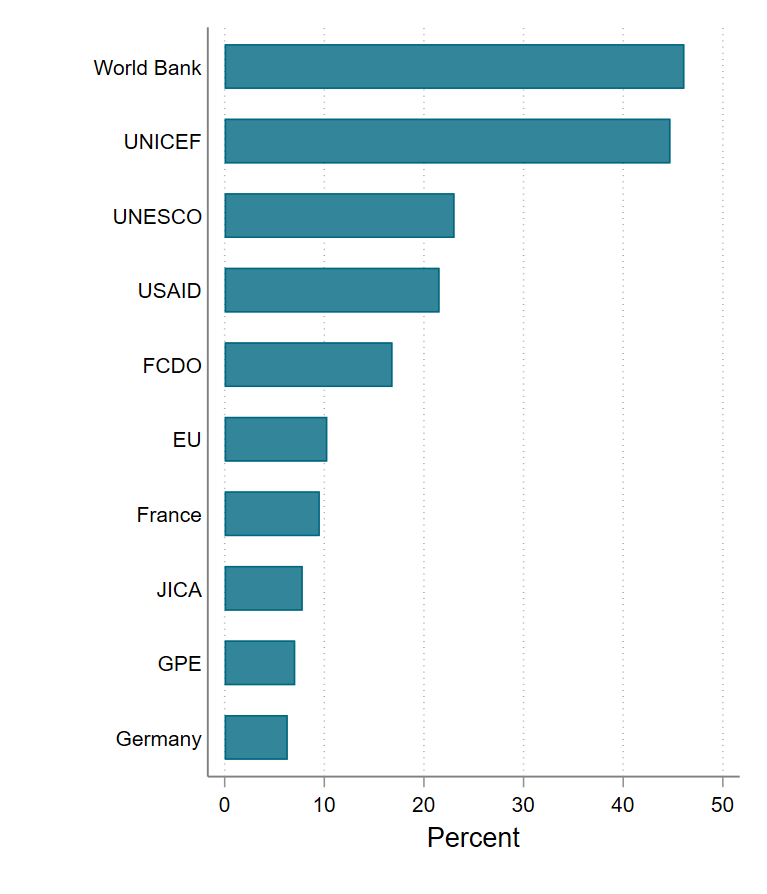

4. The World Bank and UNICEF are the most important donors

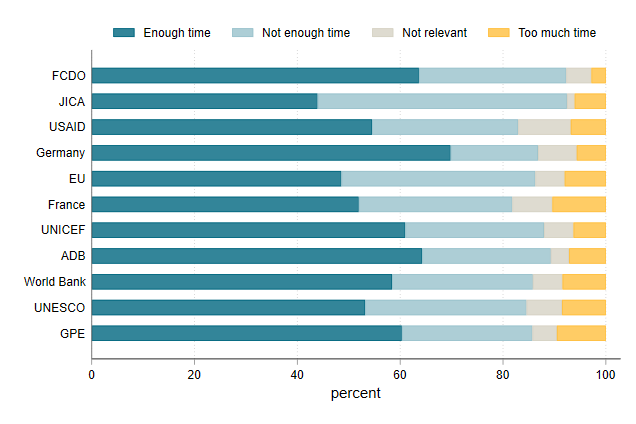

Many of the education policy conversations in Washington and London are about UNESCO, the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) and new funds such as the Education Outcomes Fund. But when we asked officials who they thought the most important development partners working in their country are (leaving “important” to be defined by them, whether by money or influence or something else), the World Bank came first, closely followed by UNICEF (figure 4).

Figure 4. The World Bank and UNICEF are rated as the most important development partners

Note: Officials were asked who the three most important three development partners in their country are.

This might be unsurprising, since the GPE typically operates through the World Bank or UNICEF as their managing grant agent, but it raises questions for the GPE. Does it want to be a fairly invisible provider of finance (that is typically relatively small in the context of national budgets)? Or does it want to have more prominence within domestic policy environments?

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.