Recommended

Last month, CGD launched the findings of the Gender Equity in Development Finance Survey, which in its first round examined 16 development finance institutions’ approaches to integrating gender into their external investing and advisory services and their internal policies and practices.

Andia Chakava, Investment Director at the Graça Machel Trust, joined our launch event to share her reflections on the survey’s formulation and findings. Here we further unpack reactions to the survey’s findings, place them within the broader context of the private investment landscape, and highlight opportunities for improvement to move the field forward.

First, a few key takeaways reflected in the survey data:

1. Room for growth: DFIs’ internal policies and practices

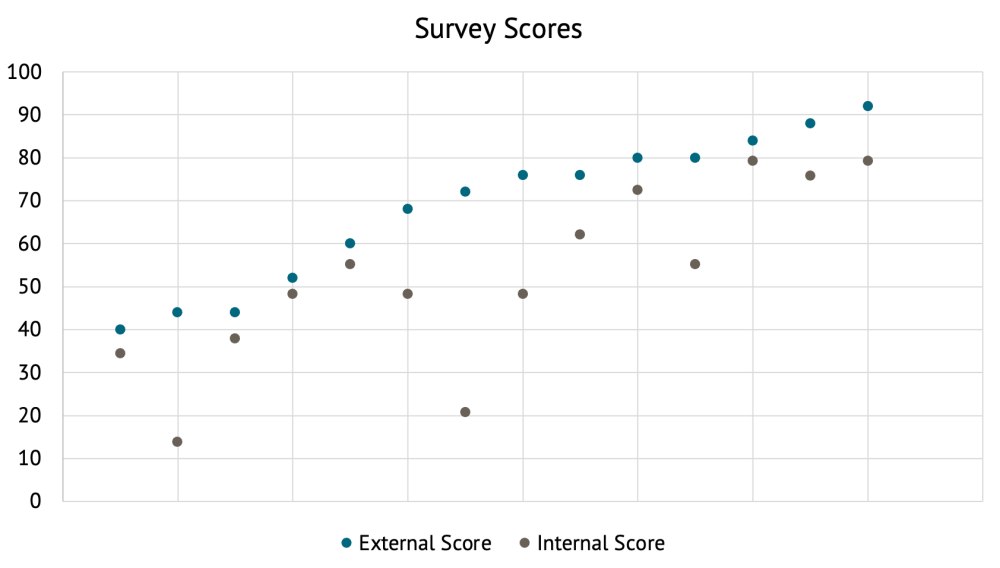

Across the board, DFIs’ internal scores were lower than their external scores, with the average external score sitting at 68 percent, compared to 52 percent on the internal side. Differences ranged from 4 to 51 points, and even a DFI’s appearance as a top performer regarding external policies and practices did not imply an equally strong performance on the internal side.

For example, on the topic of training, though a majority of DFIs (69 percent) offer gender lens investing training to their clients and partners, most (81 percent) do not currently require their own investment teams to undergo this sort of training, a reality that ultimately risks limiting their efficacy in gender lens investing, as well as their credibility in meaningfully committing to this agenda.

2. A need for gender-balanced leadership and investees

According to a 2019 Equileap report on gender equality, in over 3,500 globally listed companies, women continue to overwhelmingly occupy lower-level positions, with only 10 percent of companies having gender-balanced boards (defined as including 40 to 60 percent of each gender), and 6 percent having gender-balanced executive teams. Among these companies, women made up just 36 percent of the workforce. Worse still, in the private equity and venture capital industry, only 15 percent of senior investment teams are gender balanced and nearly 70 percent are all men.

Development finance institutions perform slightly better than their private counterparts, with women making up on average 31 percent of boards, 33 percent of senior management, and 29 percent of investment committees. That said, there is still ample room for improvement among DFIs to ensure that women are equally represented in their own workforces, especially among senior leadership, and in their investment portfolios.

Increasing investments in women will widen the deal sourcing pool and integrate a diversity of perspectives into due diligence processes and portfolio management. Women entrepreneurs tend to hire more women, and according to Graça Machel Trust research on growth barriers affecting women entrepreneurs in East Africa, at least 50 percent of women-owned businesses offer products and services that cater to other women (an underserved market segment). Just seven percent of private equity and venture capital is currently invested in women-led businesses, but women invest in almost twice as many women-led businesses than men do as deal partners.

3. Investing in new solutions to advance the field

According to Project Sage 3.0, a report by Catalyst at Large and Wharton Social Impact, there are currently 138 private funds raising capital with a gender lens, a number which has doubled since 2017. The increasing focus of these funds had broadened from North America (at 27 percent of the overall pool) to include Latin America, Asia and Sub Saharan Africa. However, due to the novelty of gender lens investing, at least 60 percent of these funds are managed by first time fund managers, and only 25 percent of the gender lens funds reviewed have met their fundraising targets. Are DFIs and other investors ready to accommodate a variety of first-time fund managers focused on gender lens investing and set targets to invest in a certain number of these funds annually?

DFIs specifically need to channel more financing to capital providers in Africa: only 33 percent of small and growing business capital providers operating in sub-Saharan Africa have received some funding from DFIs. On crowdfunding, not a single sub-Saharan African country has enabled debt and equity crowd funding for SMEs with a regulatory framework. Are DFIs and other investors going to start looking more at funding business accelerators, special purpose vehicles which favor mezzanine financing, angel networks and crowd funding initiatives to provide the “missing middle” with more viable solutions?

4. Prioritizing intersectionality

As noted by senior representatives of top-performing DFIs during our launch event, DFIs and other investors can do more to move beyond thinking of women as a monolith. Investors need to remember that women are not homogenous, and that specific efforts must be made to invest in women of diverse backgrounds, including those from different regions and sectors, as well as local indigenous women. Embracing targets that set specific benchmarks from an intersectional perspective, and tracking results against these targets, would accelerate progress.

How can CGD build on the Gender Equity in Finance Survey in its next iteration?

As Andia initially recommended, in future survey rounds, we can consider:

- The specific roles women occupy as senior managers: How many women chair investment committees, or serve as chief executive or chief investment officers?

- The role gender experts play in the investment process: What power and influence do gender experts have within their organizations? Do they sit on investment committees or have a role in approving/rejecting all investment deals?

- The gendered nature of promotion and attrition: Who is getting promoted and who is leaving? According to McKinsey’s 2019 Women in the Workplace report, the middle management pipeline is leaking. The pipeline of women climbing the career ladder will not be sufficient to maintain progress in their representation at the very top of companies. Measuring the average duration of women’s tenure at a firm is a first step to identifying the barriers to their advancement within the workplace.

- How gender intersects with race, ethnicity, age, and other demographic characteristics to better reflect intersectional diversity. A survey by Lelapa of over 100 women fund managers in Africa indicated that 57 percent had experienced racial bias.

Next steps for gender lens investing during COVID-19

Women are concentrated in sectors characterized by low pay and poor working conditions, and, according to a UN Women report, make up 70 per cent of the health and social care workforce, and they are more likely to be front-line health workers, especially nurses, midwives and community health workers. These feminized sectors are the hardest hit by the pandemic. Women are also predominant in the informal economy and rely on daily trading to support their livelihoods.

As part of Graça Machel Trust’s COVID-19 response, it partnered with Absa Bank Kenya PLC and trained over 1800 SMEs during this period to boost their confidence and provide mentorship. About 90 percent of entrepreneurs taking part in these trainings have seen a drop in cash flows due to the pandemic (with 63 percent facing a decline greater than 50 percent of pre-COVID cash flows); 58 percent have had to change their business model to maintain or grow revenues, while a further 15 percent have had to develop new products to cater to a different client base.

Some financial institutions (through guidance provided by their respective regulators like the Central Bank of Kenya) have responded to these cash flow constraints by restructuring loans for existing clients and extending repayment holidays. Gender disaggregated data on this process is opaque and we don’t yet have a clear sense of the gender breakdown of entrepreneurs receiving stop-gap financing and other relief measures. As noted by the 2X Challenge and Gender Finance Collaborative early in the pandemic, DFIs can set a strong example by investing in the collection, review and sharing of gender-disaggregated data that sheds light on this question.

DFIs and other investors can also prioritize:

- Outreach to women’s networks: Women in Investment Africa, Graca Machel Trust, and Boardroom Africa can facilitate DFIs’ increased and deepening engagement with women to ensure their perspectives and experiences are better understood.

- Building on the momentum created by 2X Challenge and other collaborative efforts to collectively implement specific and targeted programs, with an interest in early stage and ‘missing middle’ companies and innovations.

- More first time fund investment: DFIs should not behave like pure commercial investors, but instead utilize their unique position to support more first-time ventures – a way to ensure more women-led firms and funds are included in their investment portfolios.

- Narrowing the inequalities exacerbated by COVID-19 by designing specific gendered responses.

- Building the pipeline of women entrepreneurs to expand the future of investment opportunities.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: iHub/UNDP/Flickr