The post is part of a series documenting ongoing analysis of US agencies’ efforts to incorporate country ownership approaches in their development activities. The authors conducted research in Liberia from January 15 - 24, 2016.

The recent Ebola outbreak in Liberia underscored the need to focus on health systems strengthening and local resiliency. But who should take the lead? As the case of Liberia shows, even in a country still reeling from a health crisis and with perpetually low capacity, there are opportunities for donors to take a more ambitious approach to country ownership and institution strengthening.

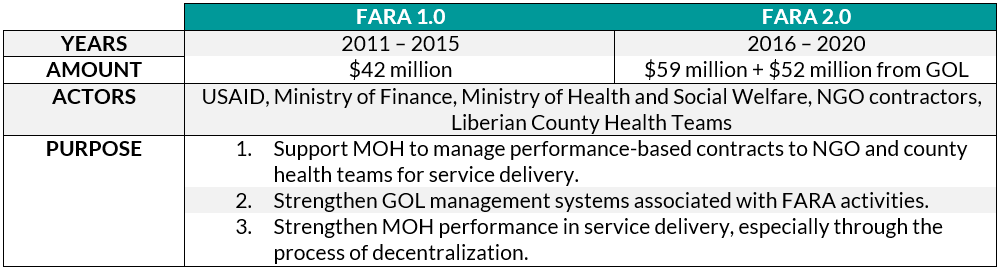

For the last five years, USAID/Liberia has partnered directly with the Ministries of Health and Finance to improve health outcomes and strengthen health systems throughout Liberia. To undertake this partnership, USAID/Liberia made use of a Fixed Amount Reimbursement Agreement (FARA), a financing mechanism that enables the use of country systems, specifically for procurement and financial management, in project implementation. The FARA allows USAID funding to flow directly through Liberia’s Ministry of Finance (MOF) to the Ministry of Health (MOH), rather than the typical USAID arrangement where funding flows through a (often non-local) non-governmental implementing partner.

Liberia’s FARA 1.0 and FARA 2.0

Around the world, USAID uses FARAs to reimburse implementers for agreed-upon deliverables that have pre-determined, fixed costs. USAID typically uses FARAs to reimburse partner governments for delivering material outputs such as roads, schools, or electricity infrastructure. FARAs are rarely used for service delivery outcomes like those envisioned in the Liberia case because estimating the costs of services is far more difficult than physical outputs. What’s more, USAID’s operational guidance recommends using this mechanism for short-term projects of two years or less – a stark difference from the consecutive five-year agreements in Liberia.

So, how did this bold application of government-to-government spending come about in Liberia’s health sector? And what does it say about USAID’s approach to ownership in a country like Liberia, where institutional capacity remains relatively low?

Can an enabling environment and political will encourage ownership?

In the post-conflict period, and specifically since 2006, USAID has worked to strengthen Liberian institutions, including the MOH, in financial management, procurement, and auditing functions. These years of capacity and relationship building between USAID and MOH laid the groundwork for USAID to incrementally shift greater financial responsibility to the Liberian government through the FARA. In addition, the government of Liberia (GOL) demonstrated political will by identifying short- and long-term needs for the health sector, and recognizing the need to strengthen its Ministry of Health to efficiently deliver essential services.

But using Liberian systems required commitment from USAID/Liberia. The Mission needed to adopt a higher level of risk-tolerance as well as expend greater time and resources. While the reimbursement mechanism shifts fiduciary risk to the Liberian government, USAID still faces programmatic, political, and reputational risks. USAID mitigated these risks by focusing on activities in the FARA that the MOH had experience implementing and USAID had experience managing through previous capacity-building activities.

How does greater ownership affect results?

While it’s too early to evaluate how greater country ownership through the FARA will affect outcomes in the health sector, the midterm evaluation of the first agreement (FARA 1.0) offers a few preliminary findings:

- Service delivery didn’t regress, as evidenced through maternal, newborn and child health indicators.

- MOH had greater stewardship and more effective management through FARA implementation.

- There was evidence of cost-savings through the use of MOH financial systems and fixed procurement costs.

Despite these gains, challenges remain. One of the biggest impediments to FARA implementation from the partner perspective is the pre-financing requirement. GOL’s budget is strained, making the process of marshalling the necessary resources for FARA activities a burden. The FARA exacerbates GOL’s liquidity constraints; in a country where development priorities are expansive, it can be difficult for MOF to front the additional resources for health-related FARA activities.

Liberia will continue to benefit from USAID assistance, but the FARA stands as a turning point. Both Liberian officials and USAID staff noted that the agreement reoriented the relationship from donor-recipient to partnership. There are now processes in place for joint decision-making about FARA activities and deliverables, use of Liberian institutions for implementation, and, in FARA 2.0, a financial contribution from GOL towards achieving project objectives. The FARA in Liberia is one example of how USAID is utilizing existing mechanisms in creative ways to encourage greater local ownership.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.