Recommended

Next week the finance ministers of the G20 countries will meet to discuss the global economic response to COVID-19. Our colleagues, and those at ODI, have called for a major scaling up of development finance in response to the pandemic. Leaving aside the pressing matter of coronavirus finance for a moment, to date, there has not been a comparable measure of government-provided development finance, with the OECD’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) only available for 13 of the G20. With a global pandemic and response, a comparable measure will be more important than ever before to ascertain the resources provided by countries in their international development efforts. In this blog, we use our new measure–Finance for International Development (FID)–to look at the G20’s finance for development and consider which countries can step up their financial contribution, both during COVID-19 and beyond.

Our new measure goes beyond ODA’s coverage in measuring financial contributions of 40 major economies, including each G20 country, and includes all cross-border finance for development on a grant-equivalent basis (from loans with a concessional element, to pure grants and multilateral contributions). Using this measure, and comparing it to the differing income levels (measured by average income per head) of the G20 countries, we find that there are eight countries who are providing less than half the FID we would expect given their individual income levels: Argentina, Australia, China, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia, the Republic of Korea, and the US. This suggests scope for larger contributions.

Given the scale of the of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is likely that many of the G20 countries will see their economies shrink in the coming year, and may face political pressure to focus their economic attention inwards. But the increased need in the developing world is large and urgent. We urge those countries providing higher-than-typical amounts to maintain their absolute value in the coming months and years, and for the remainder to step up their efforts.

Total G20 Finance for Development

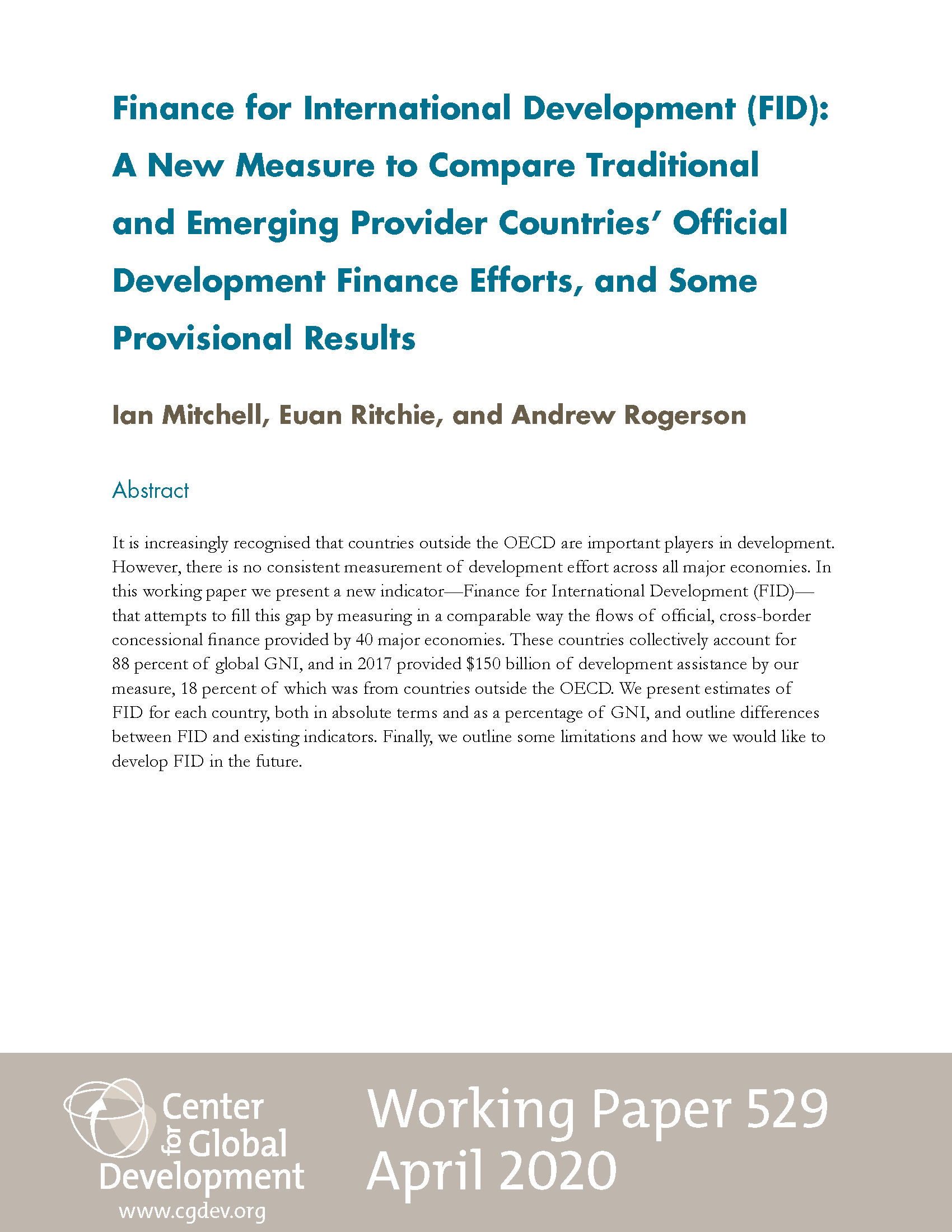

Our newly published working paper on FID estimates the grant-equivalent of official cross-border development finance consistently across 40 countries, including each of the G20 (except the EU).

Our analysis shows that, collectively, the G20 countries provided just 0.19 percent of their total income in FID (although this hides a wide range: from 1.02 percent for Turkey to 0.04 percent for China). The latest available figures (for 2017) show this amounted to $120 billion, against economies generating more than $63 trillion ($63,250bn). The country-by-country estimates are below, alongside countries’ Gross National Income (GNI).

G20 Finance for Development Summary (2017)

| FID | Multilateral | GNI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| G20 | $120bn | $36bn | $63,250bn |

| % GNI | 0.19 | 0.06 |

Source: Authors analysis of OECD CRS, official country documents, and academic estimates.

We also calculate the share of FID that goes to the core resources of the multilateral system–that is, the UN (including the WHO), the World Bank and regional banks, including newer ones like the New Development Bank and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. This accounts for under a third of total FID, at $36bn, or just 0.06 per cent of countries’ output. Put another way, for every $100 generated by the G20 economies, just 6 cents goes to the core costs of the international system. As the COVID-19 pandemic response highlights, many challenges that the world faces are truly global in nature, and therefore multilateral institutions have a key role. These numbers should be far higher if the multilateral system is to be well prepared for further challenges.

Our measure is different from (and lower than) the OECD’s Official Development Assistance measure (ODA), which includes in-country spending and is not produced for seven of the G20 (who are not members of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC)), which is used to measure progress to the UN’s development goal of 0.7 percent of GNI per country. We see that as an important goal, though one that only applies to “developed countries.” As we include a broader set of major economies–not just the richest–under half the group qualify. For countries at an earlier stage of development it is not reasonable to expect to the same level of international contributions. Below we take this difference into account.

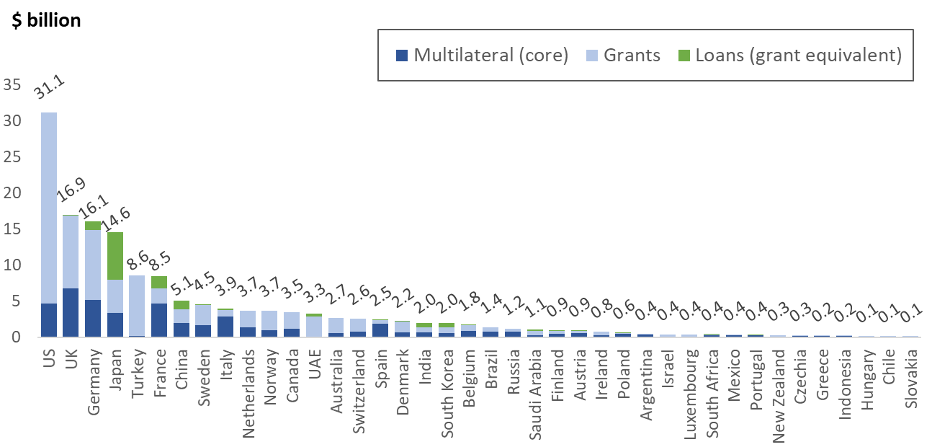

Finance contributions and income per head

Countries with higher per head incomes are able to contribute a higher percentage of this income internationally. Even for countries that met the UN’s 0.7 percent GNI target last year, it’s clear they did so on a pathway with rising income. Looking at 40 countries’ income levels, against their FID contribution, a clear pattern emerges.

Source: Authors’ analysis of OECD CRS, official country documents, World Bank data and academic estimates.

The chart shows that, generally, the share of the economy provided for development (x-axis), rises with the average income level in the economy (y-axis).

Exceptions

But there are some notable exceptions to this trend, some that are context specific and reflect particular circumstances. Turkey, through its multi-billion support to refugees in Syria, is making a major financial contribution relative to its economic size and income-level. More generally, India and South Africa also provide more than their peers. However, those countries below the line are providing less than other countries at their income level. The US contribution, which is the largest in absolute terms at $31bn, is small relative to its economy size (0.13 percent) and average income of around $60k. Comparing it to Germany, the US has four times the population (with much higher income)–but the US only provides twice the FID.

The line is not an ambition or target–rather, it is just the average. It suggests that the share of GNI provided for development typically increases by 0.08 percent of national income for every $10K increase in income per head. To be on this line countries don’t need to be especially generous: they would just need to provide what other counties at that income level do.

There are eight G20 countries who are providing less than half the FID we would expect given their individual income levels: Argentina, Australia, China, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia, the Republic of Korea, and the US; and a further six who are also under the line. For example, Brazil and Mexico both have similar income per head. But whereas Brazil contributes 0.07 percent in their income as FID, Mexico contributes less than half that figure: 0.03 percent. If these G20 countries increased their international spending to be in line with the current income-adjusted average, this would add a substantial additional resource. We estimate this would contribute around $95bn per year, and would be a large step towards the funding needed to finance global challenges such as coronavirus, and meeting the SDG targets. Even after these additional contributions, the combined FID contributed by the G20 would be just 0.32 percentage of their GNI: not a big ask for a group that contains the world’s largest economies.

Countries, particularly China, have rightly received plaudits for delivering vital medical equipment to support other countries, and demonstrating the idea that assistance is not charity from rich to poor. But these efforts are a drop in the ocean compared to the real efforts needed from countries. Our CGD colleagues have called for a moratorium on debt repayments–and for a country like China, our figures suggest this could be a way to provide immediate and substantial relief. Softer loan terms could also make a difference to China’s development effort: our colleagues find that while China’s lending terms are softer than commercial, they are still considerably harsher than World Bank concessional lending. Given it’s huge lending portfolio this would make a material difference to their development effort as measured by FID.

New G20 leadership

As the world deals with a major pandemic, the need for FID will be greater than ever. Most of the G20 will see the size of the economies (and GNI) shrink, but the absolute value of the contributions will be important to maintain, and for those already providing below typical levels, there is a compelling case to increase this contribution. To ensure its effectiveness and coordination, we would argue that at least half of that should be provided through multilateral organisations.

Of course, domestic politics will be challenging–but politicians will need to make the case that needs in poorer countries are even greater, and that a global pandemic requires it to be controlled globally.

We are grateful for comments on this blog from Andrew Rogerson and Mark Plant, any errors and views are those of the authors.

More details on G20 Finance for International Development and support to multilaterals

| Country | FID (USD million) | FID% GNI | Multilateral % GNI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 416 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Australia | 2,687 | 0.21 | 0.05 |

| Brazil | 1,426 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| Canada | 3,462 | 0.21 | 0.07 |

| China | 5,138 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| France | 8,499 | 0.32 | 0.18 |

| Germany | 16,075 | 0.43 | 0.14 |

| India | 1,971 | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| Indonesia | 181 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Italy | 3,950 | 0.20 | 0.15 |

| Japan | 14,553 | 0.29 | 0.07 |

| Mexico | 370 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Russia | 1,165 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| Saudi Arabia | 1,103 | 0.16 | 0.05 |

| South Africa | 385 | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| South Korea | 1,970 | 0.13 | 0.04 |

| Turkey | 8,571 | 1.02 | 0.02 |

| United Kingdom | 16,862 | 0.64 | 0.26 |

| United States | 31,108 | 0.16 | 0.02 |

| Total G20 | 119,892 | 0.19 | 0.06 |

Source: Authors’ analysis of OECD CRS, official country documents, World Bank data and academic estimates. See FID working paper for full details.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.