Recommended

Blog Post

REPORTS

Over the past few decades, Spain’s engagement with Latin America[1] has been inconsistent and improvised, characterized by fluctuating investments, waxing and waning geopolitical ties, shifting aid priorities, abrupt exits, and polemic debates. But the relationship between Spain and Latin America has also been substantial and even prosperous; shaped by the many changes in the 1990s, when the region started to move away from authoritarian regimes and experienced a broad push towards privatization while Spain accelerated its international outreach and the European Union (EU) became a key actor.

Despite ups and downs, Latin America is both a systemic risk and a boon to the Spanish economy.[2] In 2018, a quarter of IBEX 35[3] companies’ revenue came from Latin America, and a significant portion of the banking system’s earnings are tied to the region. In 2021, a third of Banco Santander’s revenue and half of BBVA’s originated in Latin America[4]. A potential recession in major Latin American markets would be severely damaging for Spain’s financial system. While these concerns are not currently materializing, a further worsening of external conditions—i.e., a significant contraction in advanced economies and/or China—or internal features—i.e., losing inflation expectation anchors and/or sociopolitical turmoil—could trigger new crises in the region.

In Latin America, challenges loom. The COVID pandemic was a massive human and economic hit that highlighted structural deficiencies and set back poverty and education. Firms have substantially decreased investment, and while debt overhang has not been as problematic as many expected, businesses in the region face an accelerated need to digitize, reallocate resources, and recover employment (for a detailed account of firms’ and labor markets’ situation and recommendations for policymakers see this recent CGD-IDB report). Increased poverty has erased the gains of the last 12 years, taking the region back to 2010 levels (32 percent of people live now in poverty), and extreme poverty has risen to mid-1990s levels. Inequality is also increasing—on average, Latin American children have lost 1.5 years of education, according to a World Bank and UNICEF report. Moreover, a FAO analysis found that hunger has increased by 4 million people and has doubled since 2015 and an ECLAC study showed that Latin Americans have lost three years of life expectancy due to the pandemic.

Already sluggish growth prospects have deteriorated further, and the IMF now forecasts 2.3 percent average growth for the next 5 years (2023—2027), the lowest amongst emerging and developing regions by at least 1.3 percentage points (with the exception of war-impacted Europe). Productivity challenges have been exacerbated by the pandemic, as firms have decreased in size, investment dropped, human capital was lost, and informality rose.

On the upside, the commodities boom is a positive shock to the region as most countries are net commodity exporters and their external financing needs are low, for now[5]. While the impact will be heterogeneous, and recent experiences suggest that boons are sometimes wasted in Latin America, many countries will still benefit.

In recent times, the relationship between Spain and Latin America—a strong bilateral foreign direct investment-led relationship complemented by multifaceted cultural, migratory, and political ties—has also changed substantially. Shifting geopolitical alliances, the ongoing energy crisis, and the reshaping of global value chains post-COVID only emphasize more the intricacy and importance of Latin America for Spain (and Europe). Further, Spain is leading the preparation of a EU-Latin America summit in the second half of 2023, when it will hold the Presidency of the Council of the EU, and hopes to revive stagnant free trade agreements—particularly with Mercosur—and refresh the relationship between the regions.

Given these prospects and the direct importance of Latin America for Spain’s own economy, it is the ideal time for Spain to develop a new approach across global development tools, i.e., foreign direct investment (FDI), foreign aid, and multilateral engagement and cooperation. Latin American policymakers, after a wave of discontent and elections, have renewed mandates; and the lack of leadership of the US in the region (too focused on specific topics and with little capacity to successfully convene decisionmakers and achieve substantial commitments) has created a void.

Stability and growth in Latin America are in Spain’s national interest, and relevant for the EU as a whole—new strategies that go beyond historic ties and good intentions can be a win-win in both geographies. This note lays out a brief history of investment and aid flows and suggests new directions for Spain in the coming years.

Spanish direct investment in Latin America: Essential but volatile

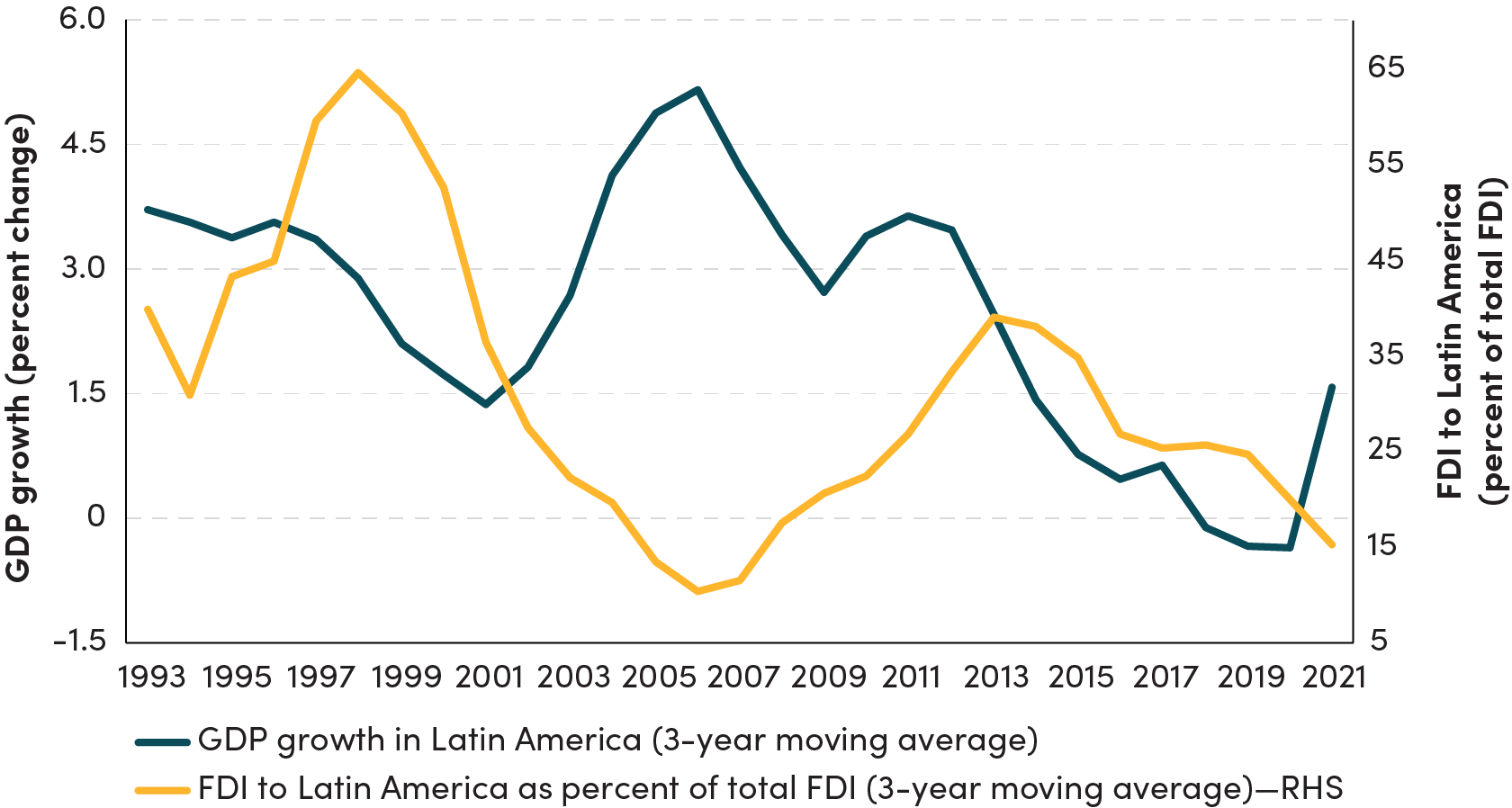

Not surprisingly, given the region’s history of capital outflows and sudden stops, Spanish FDI has fluctuated substantially over time. Figure 1 shows the 3-year moving averages of Spanish FDI in Latin America (as percentage of total Spanish FDI) and the region’s GDP growth since 1993. In the last 30 years, there is no clear correlation between the proportion of Spanish FDI and the growth rates in the region. If anything, Spanish FDI has been procyclical with a certain lag, especially in recent years, moving in the same direction as Latin America’s—and Spain’s—GDP growth.

On average, over 60 percent of Spanish FDI went to Latin America between 1996 and 2000, which is largely but not entirely driven by Repsol’s purchase of YPF in Argentina in 1999 for 16 billion dollars, but only 15 percent of FDI went to the region between 2003 and 2007. Volatility continued during the commodities’ boom and a decreasing trend started after a second peak over 40 percent in 2014. In 2021, a mere 14 percent of Spanish FDI went to Latin America.

Figure 1. Latin America’s GDP growth and Spanish FDI to Latin America (3-year moving averages; 1993-2021)

Source: IMF (October 2022 World Economic Outlook) and Spain’s Ministry of Industry, Trade and Tourism (DataInvex).

Despite these major oscillations, Spain’s FDI has been significant in the region. In the 1990s, with the expansion and consolidation of democracy and the push for privatization in many countries, large Spanish firms expanded to the region—and most became multinationals in Latin America[6]. By the late 1990s, Spain was the largest investor in the region and between 2005 and 2020, it has consistently been the second largest country of origin of FDI for the region, behind the US. Currently, Spanish companies have significant investments in the hospitality business and in the banking sector, where three Spanish banks’ subsidiaries are amongst the ten largest banks in Latin America. Moreover, this relationship goes both ways, as Latin America’s “multilatinas”[7] are also investing heavily in Spain, their preferred destination behind the US.

The expansion of Spanish investment was natural, but quickly became a bumpy road. The much-discussed Repsol-YPF case in Argentina is paradigmatic. In 2012, after being majority holder for 13 years, Repsol, which had become one of the ten largest oil producers in the world, lost control of YPF—a previously publicly owned company—when the Argentine government nationalized it amidst claims of lack of investment. In 2014 Repsol and the Argentine government reached an agreement, and Repsol received 5 billion dollars in compensation. The most ambitious expansion by a Spanish company ever almost ended with a diplomatic crisis and a huge shock to the second-largest non-financial corporation in Spain by revenue.

While the Repsol-YPF story is the most well-known, it is not an exception. Iberia also invested heavily in Argentina in the 1990s, buying the main national airline, Aerolíneas Argentinas, only to sell it shortly after to the Spanish Group Marsans. The Argentine government then expropriated Aerolíneas Argentinas, and, as in the YPF case, was ordered to pay compensation in 2019. Telefónica (the largest phone, internet, and TV provider in Spain) sold most of its business in the region in 2019, keeping a significant presence only in its main market, Brazil. Recently, Iberdrola (the third-largest energy company in Spain) has been facing major pressure from the Mexican government, finding itself in the middle of a controversial energy reform[8]. Spanish construction firms have been involved in large infrastructure projects—most notably, the expansion of the Panama Canal or the subway in Lima—that, as of 2021, had resulted in arbitrage litigations for 4.8 billion dollars[9]. Moreover, the fact that six Spanish firms, more than any other OECD country, are “black-listed” by the World Bank for corrupt practices is not particularly encouraging.

Traditionally, international firms in Latin America have been impacted by severe currency depreciations, political instability, and/or lack of judicial safety—a recent paper shows how economic policy uncertainty in Latin America hurts commercial ties and decreases exports and FDI. Now, the pandemic has accelerated a retreat in FDI (Figure 1) and the mismanagement of the multiple resulting crisis has not made the business environment more attractive, despite the unusual appreciation of many Latin American currencies in 2022. Yet, Spain’s presence in Latin America remains significant, and opportunities abound as economic activity recovers post-pandemic, digitalization efforts foster financial inclusion, and the tourism industry picks up strongly. Further policy action to improve business climate and reduce risks would be welcomed by both governments and private firms.

Spanish aid in Latin America: An odd and old special relationship

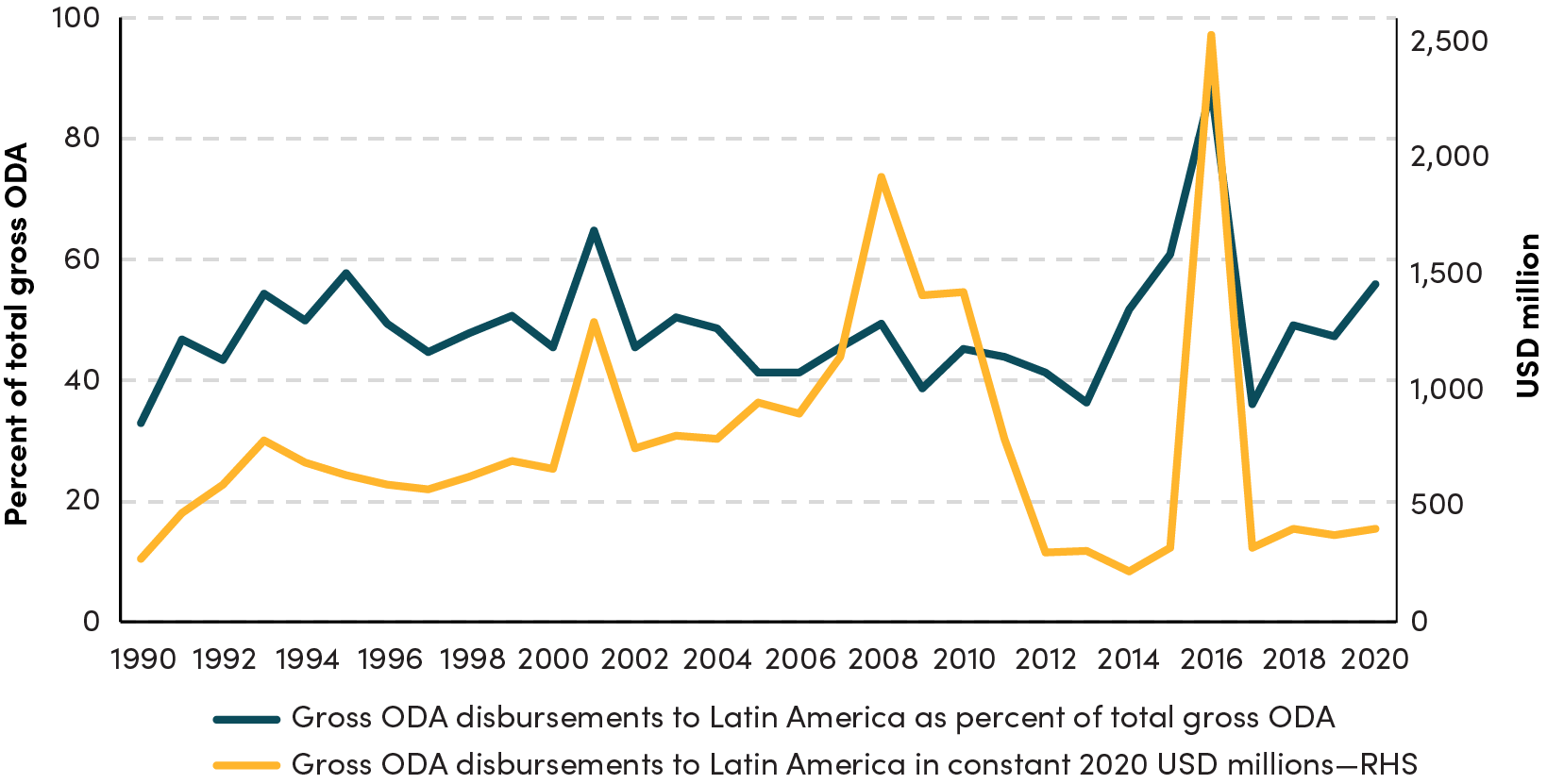

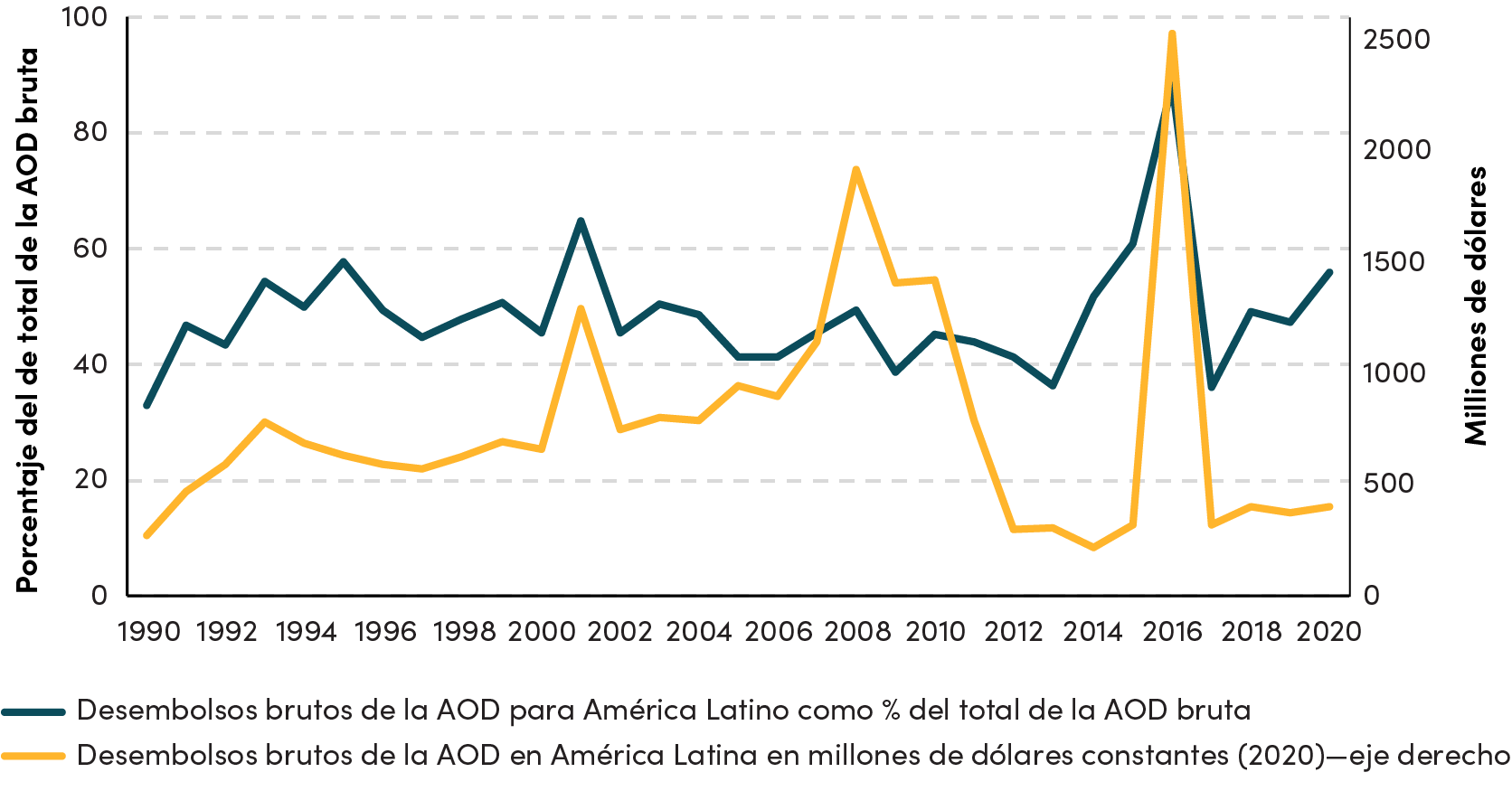

Official development assistance (ODA) provided by Spain has not been as volatile as FDI, at least when measured in terms of the proportion destined to Latin America relative to other regions, but the lack of a clear strategy and a significant budgetary reduction post 2008 crisis (Figure 2) have stifled Spain’s public involvement in the region. The fluctuations in absolute terms are considerable and suggest deeper structural issues with the way aid is managed in Spain. In relative terms, the country has been historically among the last in Europe in aid provision as a percentage of GDP—and ODA almost disappeared during the Global Financial Crisis.

In addition, priorities and the way in which aid is disbursed have changed. A report by the Real Instituto El Cano discusses a renewed emphasis on northern Africa, the increase in ODA channeled through the European Union (EU), and new areas of focus like security. Indeed, when including Spanish aid that is channeled through and managed by EU institutions into the calculation, Latin America only received 23 percent of total aid in 2019 (compared to the 47 percent of the total disbursed through Spanish institutions).

Figure 2. Spain’s gross ODA disbursements to Latin America (1990-2020)

Source: OECD (International Development Statistics).

Note: 2016 is such an extreme outlier because of a 1.5 USD billion debt relief operation in Cuba.

However, the ties remain relevant and Spain’s cooperation with Latin America has a historic basis. Out of the ten countries that received the most Spanish aid in 2020, six were Latin American (Colombia, Venezuela, El Salvador, Peru, Guatemala, and Honduras) and Spanish cooperation in the region even precedes the establishment of a dedicated global aid agency. The origin of this relationship shows how Spanish international cooperation and development aid are intrinsically linked to Latin America. The history of international development in democratic Spain dates to 1977 when the current Spanish Agency for International Cooperation and Development (AECID, Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional y Desarrollo) was the Ibero-American Center for Cooperation (CIC, Centro Iberoamericano de Cooperación), which later was renamed Institute for Ibero-American Cooperation (ICI, Instituto de Cooperación Iberoamericana). In 1988 the ICI became the AECI (the development "D" would only be added to its name in 2007). But amid all these acronyms, the Latin American (or Ibero-American) component of Spain’s aid program was diluted.

Now, a new law for “cooperation, sustainable development, and global solidarity” to replace the current one from 1998, is being discussed in the parliament. This review of Spain’s priorities and goals in development aid could change the AECID’s by-laws, allow the creation of a Spanish fund for sustainable development, and establish a legislative mandate to devote 0.7 percent of GNI to aid. These are much needed changes and a positive step forward, but the proposed legislation has flaws. As Gonzalo Fanjul argues, no one can say this is an “audacious” law: it does not renew the governance structure, it ignores decentralized cooperation, and, so far, it has lacked broad-based support in the parliament. In addition, aggregate numbers do not fully back up this apparent interest in more and better ODA; in its 2022 Development Cooperation Peer Review, the OECD criticized Spain for not having achieved the goal of allocating 0.4 percent of its GNI to ODA by 2020 (it only provided 0.2 percent) as well as several aspects of the proposed law. The 2023 budget improves this number to 0.34 percent but remains below targets. Others have also decried the lack of a comprehensive reform to the current aid system and the scarce interaction with other actors, including a disregard of the private sector role.

However, the capacity and potential for collaboration are there—Spain was the seventh largest donor of COVID vaccines in the world and the second to Latin America, and has supported Latin America in initiatives like COVAX—which makes the lack of ambition for reform and the absence of specific goals and plans for broader, more intense engagement with Latin America all the more frustrating.

Next, we further discuss why this is a unique opportunity to strengthen this relationship and outline some actions to increase and improve FDI and ODA, which should be considered state policies that are agreed and supported by both the government and opposition parties.

More and better investment and cooperation: Why now?

A structured and strategic engagement to channel investment and aid: leveraging the EU and international financial institutions

Developing a long-term view about how to engage with Latin America that aligns private interests, improves ODA disbursements, and solidifies economic and commercial ties is paramount for Spain. But, again, signals about the intent and capacity of doing so are mixed: the current Spanish strategy for foreign action for 2021-24 does not take a deep look at the region and, yet, reviving the relationship between the two regions by hosting a EU-Latin America summits—which have not taken place since 2015[10]—is one of the main international goals of Spain for 2023.

This strategy has two cornerstones that are already in place and that should be key for advancing any FDI and ODA policy: the European Union and international financial institutions (IFIs).

The European Union component should be naturally forefront in any strategy of international engagement. Spain should champion Latin America in Europe, emphasize its role as a gateway to the European market, and facilitate the channeling of European investment and aid to Latin America. The same way that Spanish firms became international firms in Latin America, many Latin American firms could see Spain as their first step towards expanding in other regions. Spain has been vocal about the European slowdown in the development and enacting of free trade agreements, particularly with Mercosur (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay) and with Chile and Mexico. Continuing to push for these types of agreements should be a policy priority for Spain. Indeed, Latin America has recently proven to be a valuable ally, partially compensating the supply chain disruption of the war in Ukraine by increasing its grain exports to Spain. Further, Europe can be a less controversial partner for the region, as it is somewhat apart from the geopolitical tensions associated with Chinese investments.

Beyond the EU-Latin America summit, broadly reinvigorating other recurrent multilateral meetings with Latin America, including the Ibero-American Summits, is low hanging fruit for Spain. The Spanish government has an opportunity to lead in the organization of such international meetings—especially after the US has experienced difficulties in doing so. And Spain should incorporate lessons learned from the EU-Africa summit earlier this year. Notwithstanding, it is often not clear what the goal of such meetings is—a good approach could be to have dedicated summits on topics in which Spain might have a comparative advantage, like global health where Spain has a major biotech and epidemiology offer, and a health system with much to teach the rest of the world. These should not be just photo-ops for policymakers but help develop new and improve existing channels for sharing knowledge. Without political support and coordination these conferences always risk being disappointing, but they can be critical in certain areas. A good example was the creation of the Ibero-American Epidemiological Observatory in the 2021 summit. Concrete action in all these meetings should be the number one priority for all the actors involved.

In addition, IFIs can help Spain effectively channel FDI and ODA[11]. Spain ought to take advantage of the full potential of the IFIs, organizations with know-how, research capabilities, experience building public and private alliances, and substantial funding capabilities.

In the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the main multilateral institution in the region, Spain has a mere 1.96 percent of the voting share (just 0.1 percentage points more than France and Germany). But given shared history and evident self-interest in Latin America, Spain should lead the European block in the IDB, perhaps spearheading a new corporate strategy and a capital replenishment to meet the moment of overlapping crises and stagnation in structural reforms needed to galvanize growth and human capital, and to address global challenges like climate change and pandemic preparedness.

Further, the head of the private sector arm of IDB (IDB Lab) and the director for Latin America of the International Finance Corporation (IFC) of the World Bank Group are Spanish nationals. Again, the human capital and the common interest is there, but a push from the corresponding authorities is needed.

Engaging with other regional institutions should also be on the agenda. The Latin American Reserve Fund (FLAR) is growing, and Spain should support this kind of initiative in any way possible. While Latin American countries have improved central bank independence, supervisory quality, and some countries have even implemented Basel III protocols to improve macrofinancial stability, much work lies ahead—and the COVID pandemic was a reminder of the importance of buffers in a region with very limited fiscal space. Helping implement countercyclical policies should always be on the agenda. Similarly, generating better and more relevant evidence for policy reforms and program adjustments to enhance efficiency is also sorely needed—a regional consortium for evidence and evaluation backed by the IDB could be part of the agenda ahead.

Spain should develop and implement action plans for FDI and ODA that align operational measures with strategic goals regarding Latin America—leveraging the EU and its bilateral relation with the region and the IFIs capabilities is a must to make these plans successful and sustainable.

Foreign direct investment

The first and foremost goal of FDI policy should be to focus on sustainable projects and initiatives that can have structural impacts—and, thus, change lives generationally. Long-term projects in strategic industries will strengthen ties and reduce the volatility that has characterized FDI in the region.

It has been reported that the EU could announce an investment package of about 8 billion dollars in the 2023 summit. Where should these funds go? There are multiple sectors of common interest, and the Spanish government has recently been pushing for Spanish firms to lead in crucial industries that could be particularly appealing for Latin America. The mix of a strong public initiative, the European financial power, and solid private capabilities could have many positive spillovers in Latin America. Three areas of particular relevance are green hydrogen, gas distribution, and semiconductors. For instance, on green hydrogen, the EU has partnered with Chile to improve investment opportunities on this field, noting that Chile could become a global leader in green hydrogen production and Spain is planning a 7 billion dollars investment in this area; and, on semiconductors, the Spanish government will have an investment of about 11 billion dollars based on European funds to strengthen and develop this industry. The ongoing energy crisis in Europe and the always present climate emergency make such efforts a no brainer.

Exchange programs to share knowledge across Latin American and Spanish/European firms and facilitating SMEs investment could consolidate this relationship. So far, large firms have led the international expansion of the Spanish private sector, and IFIs like the IDB have continued to focus on these types of companies. While large firms are crucial and valuable partners, programs that foster SMEs cooperation and investment, helping medium-size firms internationalize in Latin America would solidify economic ties.

ODA and development policy

According to the most recent Commitment to Development Index (CDI) from CGD, and out of 40 advanced economies, Spain ranks 20th overall, being in the top-10 in the investment and environmental policy categories. However, the CDI notes that the development finance component is lagging and that Spain’s finance for international development was only 0.18 percent of GNI (the CDI average is 0.29). At the current pace, it will take 4 more years to reach the goal of devoting 0.5 percent of GNI to ODA that the government set for 2023, and the government would be barely on track to reach the objective of 0.7 percent by 2030.

While these meager numbers depict the broader issue of lack of investment in development, the focus should be on quality over quantity. The 2022 OECD-DAC peer review noted that Spain needed to “streamline financial cooperation modalities,” and refocus on multi-year funding along with shorter approval and reporting processes and more focus on outcomes than inputs.

A revamping of Spanish ODA priorities can start by focusing policy on global public goods and aiming to strengthen partnerships between Spain and Latin America. On global public goods, IFIs have taken the lead, and their efforts in climate change mitigation (where the Amazon in key) and pandemic preparedness should be commended and supported. However, Spain—and Europe—should look at Latin America not as mere aid recipients but as crucial allies on these issues. Not one Latin American country had completed a self-assessment of pandemic preparedness with the World Health Organization or the Pan American Health Organization prior to COVID, despite dealing with the earlier Zika outbreak poorly, illustrating the need for further work in this area. In addition, Spanish ODA could support vaccine and medicine manufacturing in the region, aim to coordinate scientific and technology exchanges, and focus on sustainable investments to fight climate change.

To conclude, Spain’s relationship with Latin America can be mutually beneficial or stale and insignificant. There is already a shared background and multiple ties that have constructed a complicated but potentially positive connection. Now, the timing is right for Spain to launch new strategies and a new framework of bilateral, multilateral, and multiregional engagement with Latin America, in which Spain should embrace its dual role as bridge and protagonist.

[1] While acknowledging the region’s diversity, the note broadly refers to Latin America and the Caribbean. Spain’s engagement—in terms of foreign direct investment, aid, and political ties—has been focused on the larger countries, particularly Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico, which is potentially part of the problem. Expanding the outreach to other countries, recognizing the region’s diversity, and developing sustainable ties would be crucial to improve current relations along the lines suggested in this note.

[2] Indeed Latin America is the only region for which the central bank of Spain publishes biannual reports on the economic situation.

[3] Spain’s main stock market, composed of its 35 largest companies.

[4] 31 percent in South America and 3 percent in Mexico for Santander; and 45.6 percent in Mexico and 8.7 percent in South America for.

[5] With some exceptions like El Salvador.

[6] And some firms’ involvement started considerably earlier—Iberia’s first flightto Buenos Aires was in 1946, and MAPFRE, the largest Spanish insurer, started its internationalization in Colombia in 1984.

[7] Companies that operate in multiple Latin American countries.

[8] Spanish firms, like Fenosa in Dominican Republic in the early 2000s, faced complicated exitsfrom the local electricity sector.

[9] Spanish construction firms had around 30 percent of the market share in the region and almost 50 percent of their international revenue come from Latin America in 2019 and 2020.

[10] And were supposed to occur every two years.

[11] Partnerships with other development finance institutions can also be a powerful tool.

Durante las últimas décadas, el vínculo de España con América Latina[1] ha sido inconsistente e improvisado, marcado por fluctuaciones en las inversiones, lazos geopolíticos que han sufrido altibajos, cambios en las prioridades de ayuda y cooperación, salidas empresariales abruptas y debates polémicos. Pero la relación entre España y América Latina también ha sido próspera; definida por los numerosos cambios que se produjeron en la década de 1990, cuando la región comenzó a liberarse de los regímenes autoritarios y experimentó un fuerte vuelco hacia la privatización, mientras España aceleraba su proyección internacional y la Unión Europea (UE) se convertía en un actor clave.

A pesar de estos vaivenes, América Latina es la vez un riesgo sistémico y una fuente de oportunidades para la economía española.[2] En 2018, una cuarta parte de los ingresos de las empresas del IBEX 35[3]procedían de América Latina y una gran parte de los beneficios del sistema bancario está vinculada a la región; por ejemplo, en 2021, América Latina contribuyó a un tercio de los ingresos del Banco Santander y a la mitad de los del BBVA[4].Una posible recesión en los principales mercados latinoamericanos sería muy perjudicial para el sistema financiero español. Aunque estas preocupaciones no se están materializando actualmente, un mayor deterioro de las condiciones externas—por ejemplo, una contracción significativa en las economías avanzadas y/o en China—o de las internas—como la pérdida del anclaje de las expectativas de inflación y/o una mayor agitación sociopolítica—podría desencadenar nuevas crisis en la región.

En América Latina se aproximan desafíos. La pandemia del COVID tuvo un gran impacto humano y económico que puso de manifiesto deficiencias estructurales y provocó un retroceso en términos de pobreza y educación. Las empresas disminuyeron sustancialmente la inversión y, aunque el aumento de la deuda no ha sido tan problemático como se esperaba, el sector privado necesita avanzar en sus procesos de digitalización, reasignación de recursos y recuperación del empleo (para mayor detalle sobre la situación de las empresas y los mercados laborales véase este nuevo informe de CGD y el BID que incluye recomendaciones para los responsables políticos). El aumento de la pobreza ha frenado los avances conseguidos en los últimos 12 años; los indicadores han retrocedido a los niveles de 2010 (actualmente, el 32 por ciento de las personas de la región viven en la pobreza) y la pobreza extrema se ha incrementado hasta alcanzar los niveles de mediados de los 90. Por su parte, la desigualdad también está aumentando: de media, los niños latinoamericanos han perdido 1,5 años de educación, según un informe publicado por el Banco Mundial y UNICEF. Además, un análisis de la FAO reveló que el número de personas que padecen hambre se ha incrementado en 4 millones entre 2020 y 2021 y se ha duplicado desde 2015 y un estudio de la CEPAL mostró que América Latina ha perdido tres años de esperanza de vida debido a la pandemia.

Las perspectivas de crecimiento, ya de por sí bastante modestas, se han deteriorado aún más y el FMI prevé un crecimiento medio del 2,3 por ciento para los próximos 5 años (2023-2027), el más bajo entre las regiones emergentes y en desarrollo en al menos 1,3 puntos porcentuales (con la excepción de la Europa emergente, afectada por la guerra). Los problemas de productividad también se han agravado por la pandemia, ya que las empresas han disminuido su tamaño, la inversión se ha reducido, se ha perdido capital humano y ha aumentado la informalidad laboral.

Por otra parte, el auge en el precio de las materias primas tiene un impacto positivo en la región, ya que la mayoría de los países son exportadores netos de materias primas y, por el momento, las necesidades de financiación externa son bajas[5]. Pese a que este impacto será heterogéneo, y a que experiencias recientes sugieren que a veces las épocas de bonanza se desaprovechan en América Latina, muchos países se podrán beneficiar de ello.

En los últimos tiempos, la relación entre España y América Latina—una sólida relación bilateral impulsada por la inversión extranjera directa (IED) y complementada por diversos lazos culturales, migratorios y políticos—también ha variado sustancialmente. Los cambios en las alianzas geopolíticas, la actual crisis energética y la reconfiguración de las cadenas de valor mundiales tras la pandemia del COVID no hacen sino acentuar la complejidad e importancia de América Latina para España (y Europa). Además, España está liderando la preparación de una cumbre entre la Unión Europea y América Latina en el segundo semestre de 2023, cuando ejercerá la presidencia del Consejo de la UE, y donde espera reactivar los acuerdos de libre comercio estancados—en particular con Mercosur—y volver a impulsar la relación entre ambas regiones.

Dadas estas perspectivas y la importancia directa de América Latina para la propia economía española, es el momento idóneo para que España desarrolle un nuevo enfoque a través de herramientas de desarrollo global, como la IED, la ayuda exterior y la cooperación multilateral. Los responsables políticos latinoamericanos, tras una oleada de descontento y elecciones, tienen nuevos mandatos; y la falta de liderazgo de EE.UU., demasiado centrado en temas específicos y con poca capacidad para convocar con éxito a los responsables de la toma de decisiones y lograr compromisos relevantes en la región, ha generado un vacío.

La estabilidad y el crecimiento en América Latina son de interés nacional para España y relevantes para la UE en su conjunto: nuevas estrategias que vayan más allá de los lazos tradicionales y las buenas intenciones pueden favorecer la prosperidad en ambas geografías. Esta nota presenta una breve historia de los flujos de inversión y ayuda y sugiere nuevas direcciones para España en los próximos años.

Inversión directa española en América Latina: imprescindible pero volátil

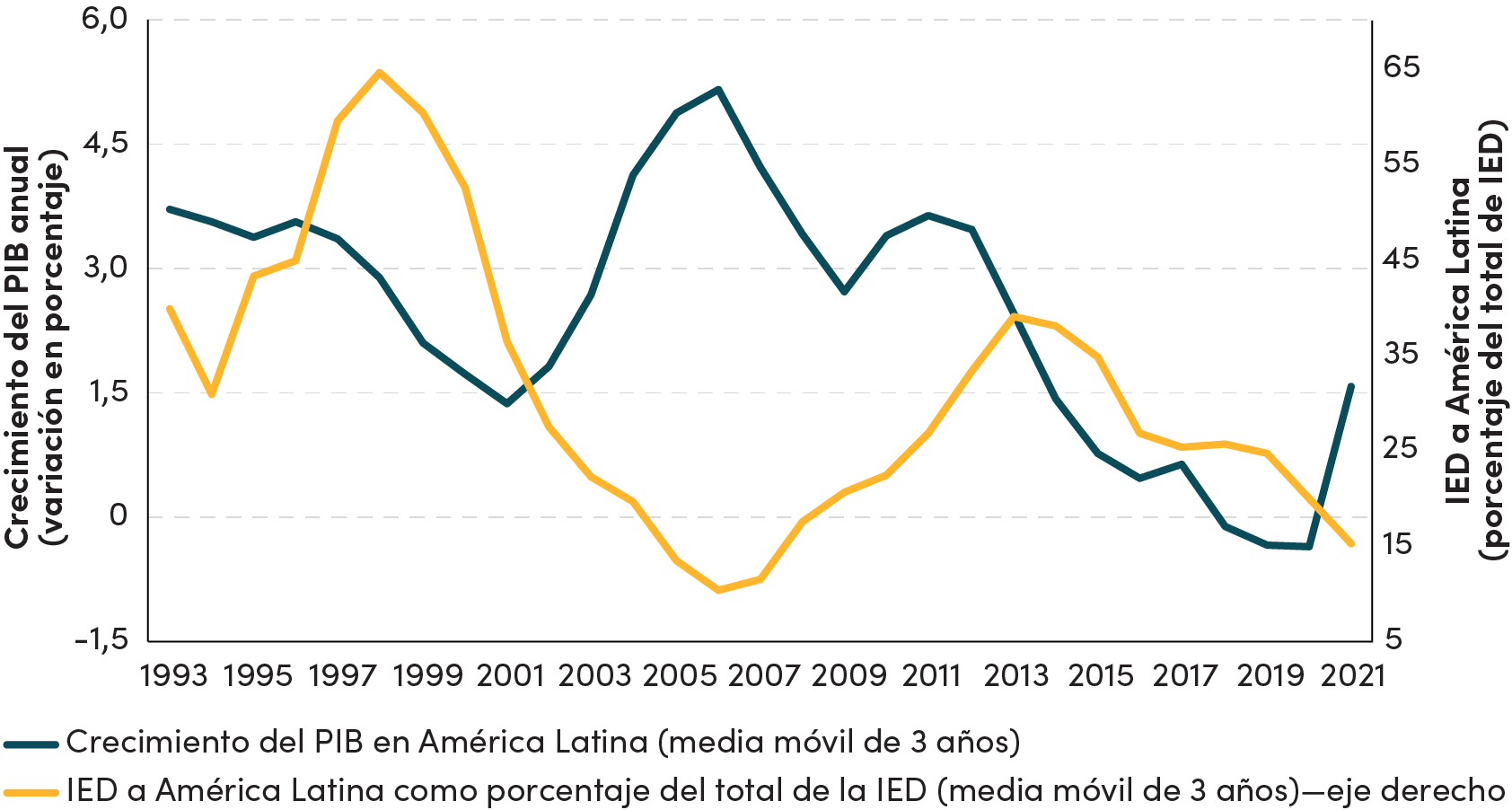

Dado el historial de fugas de capital y “sudden stops” en la región, no es de extrañar que la IED española haya fluctuado considerablemente en las últimas décadas. La Figura 1 muestra las medias móviles de tres años de la IED de España en América Latina (como porcentaje del total de la IED española) y del crecimiento del PIB de la región desde 1993. En los últimos 30 años, no existe una correlación clara entre la proporción de IED española y las tasas de crecimiento de la región. En todo caso, la IED de España ha sido procíclica con cierto retraso, especialmente en los últimos años, moviéndose en la misma dirección que el crecimiento del PIB de América Latina (y de España).

Entre 1996 y 2000, de media, más del 60 por ciento de la IED española se invirtió en América Latina, lo que se debe en gran medida, aunque no totalmente, a la compra de YPF por parte de Repsol en Argentina en 1999 por un valor de 16.000 millones de dólares. Sin embargo, entre 2003 y 2007 sólo se invirtió en la región el 15 por ciento de la IED. La volatilidad continuó durante el auge de las materias primas y se inició una tendencia a la baja tras un segundo repunte superior al 40 por ciento en 2014. En 2021, apenas un 14 por ciento de la IED española se dirigió a América Latina.

Figura 1. Crecimiento del PIB de América Latina y la inversión española en América Latina (medias móviles de 3 años; 1993-2021)

Fuente: FMI (perspectivas de la economía mundial, octubre de 2022) y Ministerio de Industria, Comercio y Turismo de España (DataInvex).

A pesar de estas oscilaciones, la IED de España ha sido muy relevante en la región. En los años 90, con el avance y la consolidación de la democracia y el impulso que muchos países dieron a la privatización, las grandes empresas españolas se expandieron en la región y, de hecho, la mayoría se convirtieron en multinacionales en América Latina6. A finales de la década de 1990, España era el mayor inversor en la región y, entre 2005 y 2020, ha sido sistemáticamente el segundo país de origen de la IED, por detrás de Estados Unidos. En la actualidad, las empresas españolas tienen considerables inversiones en hostelería y en el sector bancario, donde tres filiales de bancos españoles se encuentran entre los diez mayores bancos de América Latina. Además, esta relación funciona en ambos sentidos, ya que las "multilatinas"[7] también están invirtiendo en España, siendo su destino de preferencia por detrás de Estados Unidos.

La expansión de las inversiones españolas ocurrió de forma natural, pero pronto se convirtió en un camino lleno de baches. El polémico caso Repsol-YPF en Argentina es paradigmático. En 2012, después de ser accionista mayoritario durante 13 años, Repsol, que se había convertido en uno de los diez mayores productores de petróleo del mundo, perdió el control de YPF—una empresa que históricamente había sido de titularidad pública—cuando el gobierno argentino nacionalizó la compañía, alegando falta de inversión. En 2014, Repsol y el gobierno argentino llegaron a un acuerdo y Repsol recibió 5.000 millones de dólares de compensación. La expansión más ambiciosa hasta la fecha de una empresa española estuvo al borde de terminar en una crisis diplomática y fue un duro golpe para la segunda empresa no financiera más grande de España en términos de ingresos.

Aunque la historia de Repsol-YPF es la más conocida, no es una excepción. Iberia también invirtió en Argentina en los años 90, adquiriendo Aerolíneas Argentinas, la principal aerolínea nacional, y acabó vendiéndola poco después al grupo español Marsans. El gobierno argentino expropió más tarde Aerolíneas Argentinas y, como en el caso de YPF, fue condenado a pagar una indemnización en 2019. Ese mismo año, Telefónica (el mayor proveedor de telefonía, internet y televisión de España) vendió la mayor parte de su negocio en la región, manteniendo una presencia significativa sólo en Brasil, su mercado principal. Recientemente, Iberdrola (la tercera empresa energética de España) se ha visto sometida a importantes presiones por parte del gobierno mexicano y se encuentra en medio de una polémica reforma energética[8]. Las constructoras españolas han intervenido en grandes proyectos de infraestructuras—entre los que destacan la ampliación del Canal de Panamá o el metro de Lima—que, hasta 2021, habían dado lugar a litigios de arbitraje por 4.800 millones de dólares[9]. Además, el hecho de que seis empresas españolas, más que cualquier otro país de la OCDE, estén en la "lista negra" del Banco Mundial por prácticas corruptas no es especialmente alentador.

Históricamente, las empresas internacionales que invierten en América Latina se han visto afectadas por fuertes depreciaciones de sus monedas, inestabilidad política y/o falta de seguridad judicial; un informe publicado recientemente muestra cómo la incertidumbre de la política económica en América Latina debilita los vínculos comerciales y disminuye las exportaciones y la IED. Ahora, la pandemia ha acelerado la retirada de la inversión (Figura 1) y la mala gestión de las múltiples crisis resultantes no ha hecho más atractivo el entorno empresarial, a pesar de la inusual apreciación de muchas monedas latinoamericanas en 2022. Sin embargo, la presencia de España en América Latina sigue siendo significativa y están surgiendo nuevas oportunidades gracias a que la actividad económica se normaliza tras la pandemia, a los esfuerzos de digitalización que fomentan la inclusión financiera y a que la industria del turismo se recupera con fuerza. Medidas adicionales para mejorar el clima empresarial y reducir los riesgos serían bien acogidas tanto por los gobiernos como por las empresas privadas.

La ayuda española en América Latina: una antigua y extraña relación especial

La ayuda oficial para el desarrollo (AOD) de España no ha sido tan volátil como la IED, al menos en términos de la proporción destinada a América Latina en relación con otras regiones. Sin embargo, la falta de una estrategia clara y una importante reducción presupuestaria tras la crisis de 2008 (Figura 2) han frenado la implicación pública de España en la región. Las fluctuaciones en términos absolutos son significativas y sugieren problemas estructurales más profundos en la gestión de la ayuda en España. En términos relativos, el país ha estado históricamente a la cola de Europa en cuanto a los niveles totales de ayuda como porcentaje del PIB y la AOD estuvo a punto de desaparecer durante la crisis financiera global.

Figura 2. Desembolsos brutos de la ayuda oficial al desarrollo de España en América Latina (1990-2020)

Fuente: OCDE (Estadísticas de Desarrollo Internacional).

Nota: El pico registrado en 2016 se debe a la condonación de la deuda de Cuba por 1.500 millones de dólares.

Además, las prioridades y la forma de desembolso de la AOD han ido cambiando. Un informe del Real Instituto Elcano trata el nuevo enfoque en el norte de África, el aumento de la AOD canalizada a través de la Unión Europea y las nuevas áreas de interés, como la seguridad. De hecho, al incluir en el cálculo la ayuda española canalizada y gestionada por las instituciones de la UE, América Latina sólo recibió el 23 por ciento del total de la ayuda en 2019 (frente al 47 por ciento del total desembolsado a través de las instituciones españolas).

Sin embargo, los lazos siguen siendo importantes y la cooperación de España con América Latina tiene una base histórica. En 2020, seis de los diez países que más ayuda española recibieron eran latinoamericanos (Colombia, Venezuela, El Salvador, Perú, Guatemala y Honduras) y la cooperación española en la región se remonta incluso a antes de la creación de una agencia de ayuda global específica. El origen de esta relación muestra como la cooperación internacional y la ayuda al desarrollo están intrínsecamente ligadas a América Latina. La historia del desarrollo internacional en la España democrática se remonta a 1977 cuando la actual Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional y Desarrollo (AECID) era el Centro Iberoamericano de Cooperación, que más tarde pasó a ser el Instituto de Cooperación Iberoamericana (ICI). En 1988 el ICI se convirtió en AECI (la "D" de desarrollo no se añadiría hasta 2007). Pero, en algún momento, el componente latinoamericano (o iberoamericano) de los programas de ayuda de España se diluyó entre todos estos acrónimos.

En la actualidad se está elaborando una nueva ley de "cooperación, desarrollo sostenible y solidaridad global" en el Parlamento, que sustituya a la actual de 1998. Esta revisión de las prioridades y objetivos de España en materia de ayuda al desarrollo podría modificar los estatutos de la AECID, permitir la creación de un fondo español para el desarrollo sostenible y establecer un mandato legislativo para destinar el 0,7 por ciento de la renta nacional bruta a la ayuda. Sin embargo, a pesar de ser cambios muy necesarios y que suponen un avance positivo, el anteproyecto tiene algunos defectos. Como señala Gonzalo Fanjul, no se puede decir que sea una ley que destaque por su "audacia": no renueva la estructura de gobierno, ignora la cooperación descentralizada y, hasta ahora, ha carecido de apoyo generalizado en el parlamento. Es más, las cifras agregadas no terminan de sustentar este manifiesto interés por mas y mejor AOD; en el “Peer Review” (Examen de Pares) de la Cooperación al Desarrollo de 2022, la OCDE criticó a España por no haber alcanzado el objetivo de destinar el 0,4 por ciento de la RNB a la AOD para el año 2020 (sólo dirigió el 0,2 por ciento), así como otros aspectos del anteproyecto de ley. El presupuesto de 2023 mejora esta cifra hasta el 0,34 por ciento, pero sigue estando por debajo de los objetivos. Otros autores han señalado también la falta de una reforma integral del modelo actual de ayuda y la escasa interacción con otros actores, incluyendo el sector privado, al que se le ha otorgado un papel marginal.

No obstante, la capacidad y el potencial de colaboración están presentes—España ha sido el séptimo donante mundial de vacunas contra el COVID y el segundo en América Latina y ha apoyado a la región en iniciativas como COVAX—lo que hace que la falta de ambición para lograr reformas y la ausencia de objetivos y planes específicos para una colaboración más amplia e intensa con América Latina sean aún más frustrantes.

A continuación, exponemos más a fondo por qué existe una oportunidad única para fortalecer esta relación y esbozamos algunas acciones para aumentar y mejorar la IED y la AOD, que además deberían considerarse políticas de Estado acordadas y apoyadas tanto por el gobierno como por los partidos de la oposición.

Más y mejor inversión y cooperación: ¿por qué ahora?

Un compromiso estructurado y estratégico para canalizar la inversión y la ayuda: sacar el máximo partido a la UE y las instituciones financieras internacionales

Para España es primordial desarrollar una visión a largo plazo para colaborar con América Latina que coordine los intereses privados, mejore los desembolsos de la AOD y consolide los lazos económicos y comerciales. Pero, una vez más, las señales sobre las intenciones y la capacidad de llevar esta visión a cabo son contradictorias: la estrategia española actual de acción exterior para 2021-24 no considera en profundidad el papel de la región, y, sin embargo, uno de los principales objetivos internacionales de España para 2023 es relanzar la relación entre ambas regiones acogiendo la cumbre UE-América Latina—que no se celebra desde 2015[10].

Esta estrategia tiene dos piedras angulares que deben ser clave para avanzar en cualquier política de IED y de AOD: la UE y las instituciones financieras internacionales.

El componente de la UE debe ser central en cualquier estrategia de política internacional. España puede abogar por América Latina en Europa, enfatizar su papel como puerta de entrada al mercado europeo y facilitar las inversiones y ayudas europeas en América Latina. Del mismo modo que las empresas españolas se convirtieron en empresas internacionales en América Latina, muchas empresas latinoamericanas podrían ver a España como su primer paso para expandirse en otras regiones. España ha mostrado malestar por la ralentización europea en el desarrollo y promulgación de acuerdos de libre comercio, especialmente con Mercosur (Argentina, Brasil, Paraguay y Uruguay) y con Chile y México. Seguir impulsando este tipo de acuerdos tiene que ser una prioridad política para España. De hecho, América Latina ha demostrado recientemente ser un aliado de gran valor, compensando en parte la interrupción de la cadena de suministro derivada de la guerra en Ucrania mediante el aumento de sus exportaciones de grano a España. Además, Europa podría ser un socio menos conflictivo para la región, al estar relativamente al margen de las tensiones geopolíticas asociadas a las inversiones chinas.

Independientemente de la cumbre UE-América Latina, relanzar otras reuniones multilaterales recurrentes con América Latina, incluidas las Cumbres Iberoamericanas, es una oportunidad al alcance de la mano para España. El gobierno español tiene la oportunidad de liderar la organización de estas reuniones internacionales, especialmente después de que Estados Unidos haya mostrado sus limitaciones en este terreno. Asimismo, España puede incorporar las lecciones aprendidas en la cumbre UE-África de este año. Aunque en muchas ocasiones no está claro cuál es el objetivo de estas reuniones, un buen enfoque puede ser el celebrar cumbres dedicadas a temas en los que España tiene una ventaja comparativa, como por ejemplo la salud global, donde España cuenta con una amplia oferta de biotecnología y epidemiología, y un sistema sanitario del que el resto del mundo tiene mucho que aprender. Estas conferencias no deben ser sólo una oportunidad para sacarse fotos, sino que tienen que contribuir a desarrollar nuevos canales para compartir conocimientos y a mejorar los existentes. Sin apoyo y coordinación política, estas conferencias corren el riesgo de ser un fracaso, pero también pueden ser fundamentales en determinados ámbitos. Un buen ejemplo es la creación del Observatorio Epidemiológico Iberoamericano en la cumbre de 2021. Tomar acciones concretas en estas reuniones tiene que ser algo prioritario para todos los actores involucrados.

Por otro lado, las instituciones financieras internacionales pueden ayudar a España a canalizar de manera eficaz la IED y la AOD.[11] España debe aprovechar todo su potencial, al tratarse de organizaciones que tienen conocimientos técnicos necesarios, capacidad de investigación, experiencia en la creación de alianzas públicas y privadas y una gran capacidad de financiación.

En el Banco Inter-Americano de Desarrollo (BID), la principal institución multilateral de la región, España sólo cuenta con un 1,96 por ciento de la cuota de votos (apenas 0,1 punto porcentual más que Francia y Alemania). Sin embargo, dada la historia que comparten y el patente interés propio en América Latina, España debería liderar el bloque europeo en el BID, quizás incluso encabezando una nueva estrategia corporativa y una dotación de capital para hacer frente a la situación actual de crisis superpuestas y al estancamiento de las reformas estructurales necesarias para impulsar el crecimiento y el desarrollo y también para abordar retos globales, como el cambio climático y la preparación ante futuras pandemias.

Además, el director del brazo del sector privado del BID (BID Lab) y el director de América Latina de la Corporación Financiera Internacional del Grupo del Banco Mundial son de nacionalidad española. De nuevo, el capital humano y el interés común están ahí, pero es necesario el impulso por parte de las autoridades correspondientes.

El compromiso con otras instituciones regionales también debe estar en la agenda. El Fondo Latinoamericano de Reservas (FLAR) está creciendo y España ha de apoyar este tipo de iniciativas de todas las formas que sea posible. Aunque los países latinoamericanos han mejorado la independencia de los bancos centrales y la calidad de la supervisión, y algunos países incluso han implementado los protocolos de Basilea III para mejorar la estabilidad macrofinanciera, queda aún mucho trabajo por delante y la pandemia del COVID ha vuelto a recordar la importancia de los colchones en una región con un espacio fiscal muy limitado. Ayudar a aplicar políticas anticíclicas ha de estar siempre en la agenda. Del mismo modo, también es muy necesario obtener datos mejores y más pertinentes para lograr reformas políticas y ajustes de los programas con el fin de mejorar la eficiencia; un consorcio regional de datos y evaluación apoyado por el BID también podría formar parte de la agenda futura.

España debe desarrollar e implementar planes de acción para la IED y la AOD que alineen las medidas operativas con los objetivos estratégicos relacionados con América Latina; es imprescindible aprovechar la relación bilateral de la UE con la región y las capacidades de las instituciones financieras internacionales para que estos planes tengan éxito y sean sostenibles en el tiempo.

Inversión extranjera directa

El primer y principal objetivo de la política de IED debe ser el poner foco en proyectos e iniciativas sostenibles que puedan tener un efecto estructural y, por tanto, un impacto intergeneracional. Los proyectos a largo plazo en industrias estratégicas reforzarán los vínculos y reducirán la volatilidad que ha caracterizado a la IED en la región.

Se ha revelado que la UE podría anunciar un paquete de inversiones de unos 8.000 millones de dólares en la cumbre de 2023. ¿Hacia dónde habría que dirigir estos fondos? Hay múltiples sectores de interés común y el Gobierno español ha estado impulsando el liderazgo de las empresas españolas en industrias clave que podrían ser especialmente atractivas para América Latina. La combinación de una sólida iniciativa pública, el poder financiero de Europa y las grandes capacidades privadas podrían tener numerosos efectos positivos en América Latina. Hay tres áreas que son particularmente relevantes: el hidrógeno verde, la distribución de gas y los semiconductores. Por ejemplo, en lo que respecta al hidrógeno verde, la UE se ha asociado con Chile para mejorar las oportunidades de inversión en este campo, señalando que Chile podría convertirse en líder mundial en la producción de hidrógeno verde y que España está planeando movilizar 7.000 millones de dólares en este sector; y, en lo que respecta a los semiconductores, el gobierno español realizará una inversión de unos 11.000 millones de dólares apoyada con fondos europeos para fortalecer y desarrollar esta industria. La crisis energética actual en Europa y la siempre presente emergencia climática hacen que estos esfuerzos sean ineludibles.

Los programas de intercambio de conocimientos entre empresas latinoamericanas y españolas/europeas y facilitar la inversión de las pymes podrían consolidar esta relación. Hasta ahora, las grandes empresas han liderado la expansión internacional del sector privado español y las instituciones financieras internacionales, como el BID, han seguido centrándose en este tipo de empresas. Aunque las grandes empresas son socios fundamentales y de gran valor los programas que fomenten la cooperación y la inversión de las pymes, ayudando a las medianas empresas a lograr la internacionalización en América Latina, consolidarían los vínculos económicos.

Ayuda oficial al desarrollo y política de desarrollo

Según el último Índice de Compromiso con el Desarrollo (CDI) del CGD, España ocupa el puesto 20 en la clasificación general entre 40 economías avanzadas, estando entre los 10 primeros en las categorías de inversión y política medioambiental. Sin embargo, el CDI señala que el componente de financiación del desarrollo está rezagado y que la financiación de España para el desarrollo internacional fue sólo del 0,18 por ciento de la renta nacional bruta (RNB), cuando la media del CDI es del 0,29 por ciento. A este ritmo, se necesitarán 4 años más para alcanzar el objetivo que el gobierno estableció de dedicar el 0,5 por ciento de la RNB a la AOD en 2023; y el gobierno apenas está camino de alcanzar el objetivo del 0,7 por ciento para 2030.

Si bien estas modestas cifras reflejan un problema más amplio, como es la falta de inversión en el desarrollo, habría que poner el foco en la calidad más que en la cantidad. Un informe de la OCDE señaló en 2022 que España necesitaba "simplificar las modalidades de cooperación financiera" y volver a centrarse en la financiación plurianual, además de acortar los procesos de aprobación y presentar informes más breves y enfocados en los resultados en vez de en las contribuciones.

Una revisión de las prioridades de la AOD española podría empezar por centrar las políticas en los bienes públicos globales y tratar de reforzar las alianzas entre España y América Latina. En cuanto a los bienes públicos globales, las instituciones financieras internacionales han tomado la delantera y sus esfuerzos por mitigar el cambio climático (en lo que la Amazonia es crucial) y la preparación para las pandemias han de ser reconocidos y apoyados. Sin embargo, España—y Europa—deben considerar a los países de América Latina no como meros receptores de ayuda, sino como aliados clave en estas cuestiones. Ningún país latinoamericano había completado la evaluación de su preparación para pandemias con la Organización Mundial de la Salud ni con la Organización Panamericana de Salud antes del COVID, pese a haber tenido dificultades para afrontar el anterior brote de Zika; lo cual muestra la necesidad de seguir trabajando en este ámbito. Además, la AOD española podría apoyar la capacidad productiva de vacunas y medicamentos en la región, tratar de coordinar los intercambios científicos y tecnológicos y centrarse en inversiones sostenibles para luchar contra el cambio climático.

En resumen, la relación de España con América Latina puede ser beneficiosa para ambas regiones u obsoleta e insignificante. El contexto y los múltiples lazos que comparten ambas regiones han generado un vínculo complejo, pero potencialmente muy positivo. Nos encontramos en el momento adecuado para que España ponga en marcha nuevas estrategias y un nuevo marco de compromisos bilaterales, multilaterales y multirregionales con América Latina, en el que España debe asumir el doble papel de puente y protagonista.

Alejandro Fiorito fue investigador asociado en el Center for Global Development

Amanda Glassman es vicepresidenta ejecutiva e investigadora principal del Center for Global Development (Centro para el Desarrollo Global).

[1] La nota se refiere de manera general a América Latina y el Caribe, si bien se reconoce la diversidad existente en la región. El compromiso de España—en términos de inversión extranjera directa, ayudas y vínculos políticos—se ha centrado en los países más grandes, especialmente en Argentina, Brasil y México, lo que constituye potencialmente parte del problema. Ampliar el alcance a otros países, reconocer la diversidad de la región y desarrollar vínculos sostenibles es clave para mejorar las relaciones actuales en línea con lo sugerido en esta nota.

[2] De hecho, América Latina es la única región para la que el banco central de España publica informes semestrales sobre su situación económica.

[3]El principal mercado de valores de España, compuesto por las 35 empresas más grandes del país.

[4] En el caso del Banco Santander, Sudamérica contribuye el 31 por ciento y México el 3 por ciento; y en el del BBVA, el 45,6 por ciento de los ingresos provienen de México y el 8,7 por ciento de Sudamérica.

[5] Con algunas excepciones como El Salvador.

[6] Y la participación de algunas empresas empezó mucho antes: elprimer vuelo de Iberia a Buenos Aires fue en 1946 y MAPFRE, la mayor aseguradora española, comenzó su internacionalización en Colombia en 1984./p>

[7] Empresas que operan en varios países de América Latina

[8] Otras empresas españolas, como Fenosa en República Dominicana a principios de la década de 2000, se enfrentaron a salidas complicadasfdel sector eléctrico local.

[9] En 2019 y 2020, las constructoras españolas tenían alrededor del 30 por ciento de la cuota de mercado en la región y casi el 50 por ciento de sus ingresos internacionales provenían de América Latina.

[10] Y que debía organizarse cada dos años.

[11] Las alianzas con otras instituciones internacionales de desarrollo también podrían ser herramientas potentes.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.