Growing interest in whether and how blockchain technology can help address a variety of social and economic challenges has given rise to a community of thinkers, innovators, and policymakers working to explore the technology’s implications for social impact and development.

On one level, things are happening quickly in this space. Over the last two years, the largest development organizations have begun to examine how using the technology might help them meet their goals. This includes the World Bank, which established a Blockchain Lab in 2017; the United Nations, which reports that 15 UN entities are carrying out blockchain initiatives; the Inter-American Development Bank, which is exploring the use of blockchain as a platform for asset registries; and USAID, which recently a published a primer on the topic.[1] Several humanitarian non-profit organizations (NPOs) are also evaluating blockchain as a potential platform for aid distribution and developing their own proofs-of-concept. This is all happening as the number of start-ups pitching ideas continues to grow and distributed ledger models continue to evolve.

Despite these advances, however, the number of pilot projects underway remains quite small. While this could be just a matter of timing—many of the organizations mentioned above are now reviewing project proposals—it may also reflect hurdles to implementation that have received insufficient attention to date.

Given that blockchain technology is still in an early stage of development, it makes sense that most discussions about its use have focused on its potential rather than obstacles. Too often, however, boosters of the technology have overstated its capabilities and failed to consider obstacles to adoption. This imbalance has led to unrealistic expectations about what blockchain solutions can do, how easy they will be to implement, and how quickly they can scale, if at all. The result has been a widening gap between expectations and reality that has naturally led to growing skepticism.

The best way to address these doubts is to take them head on and to rebalance the conversation away from starry-eyed accounts of the technology’s promise and towards the obstacles that are likely to slow implementation and the steps that must be taken to overcome them.

This brief essay explores a key but often overlooked hurdle to using blockchain solutions, which is the complexity that decentralized solutions necessarily introduce. At times, the benefits of such solutions appear to exceed the added cost of complexity but often they do not. With this tradeoff in mind, the paper considers two use cases, digital ID and health supply chain management. Finally, the paper offers recommendations about how the development community can shift the conversation in a more useful direction.

Understandable excitement leads to unrealistic expectations

Enthusiasm over the potential of blockchain technology to address a wide variety of social and economic challenges is largely based on the notion that it allows for “trustless collaboration.” This widely held view is captured in a recent report co-published by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the company Blockchain, which states that “the decentralized, transparent, verifiable nature of [blockchain] means we can trust people and organizations precisely because trust is no longer an issue.”[2]

The notion that the technology can substitute for trustful relationships is, in most cases, misguided. By solving the “double spend” problem, the original blockchain outlined by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2008 removed the need to rely on trusted intermediaries to oversee the transaction of digital assets. However, when the problems we want to solve involve changes in the real “off-chain” world, the need for human agency, and therefore trust, remains.[3] For example, creating a blockchain-based land registry does not remove the need to trust the bureaucrats who upload land titles because, like all databases, blockchain does nothing to improve the reliability of inputs. At best, the technology can enhance trust in some relationships by increasing the transparency and immutability of transactions and records.

It is also important to recognize that, while early excitement about blockchain focused on the transformative potential of public, permissionless networks like Bitcoin and Ethereum, interest and investment has shifted strongly towards permissioned ledgers, in which only verified parties can participate. These closed networks are much more likely to help centralized actors achieve efficiency gains than they are to lead to their displacement.

The Cost of Complexity

As noted above, much of blockchain’s appeal rests on the often-mistaken notion that it can remove the need to rely on trusted third parties. Yet even when the assumption holds, moving from a centralized to a decentralized solution always comes at the cost of added complexity.

This increased complexity can take different forms. At the most basic level, moving from a system in which a single actor verifies who owns what to one in which many actors share this responsibility requires using a consensus protocol, even the most efficient of which adds delay.

Likewise, moving from a system in which a trusted third-party stores data in a centralized “silo” to one in which data is stored on a distributed network often requires adding layers of encryption to control who can see what. While some of these encryption approaches are no more complex than those used by centralized databases, others, like those that rely on zero knowledge proofs, are more computationally intensive.[4] In addition, the cost of permanently storing documents on an ever-growing blockchain will inevitably force organizations to develop off-chain storage solutions, which will further complicate how data is managed and secured.

Additional layers of complexity may be required depending on use case. For example, using blockchain as a platform for digital ID raises the question of how individuals manage their private keys.

Perhaps the biggest challenges raised by shifting from centralized to decentralized models relate to legal and regulatory considerations. In the first instance, companies interested in using the technology must determine how they can comply (if at all) with existing data security and privacy laws. In the second, policymakers must consider whether to change existing laws to facilitate the use of decentralized models. As Graglia and Mellon note, “blockchain is unusual in that it is a social technology, designed to govern the behavior of groups of people through social and financial incentives. It is therefore inherently political.”[5] For that reason, developing reforms aimed at supporting decentralized approaches could take a significant amount of time and be contentious.

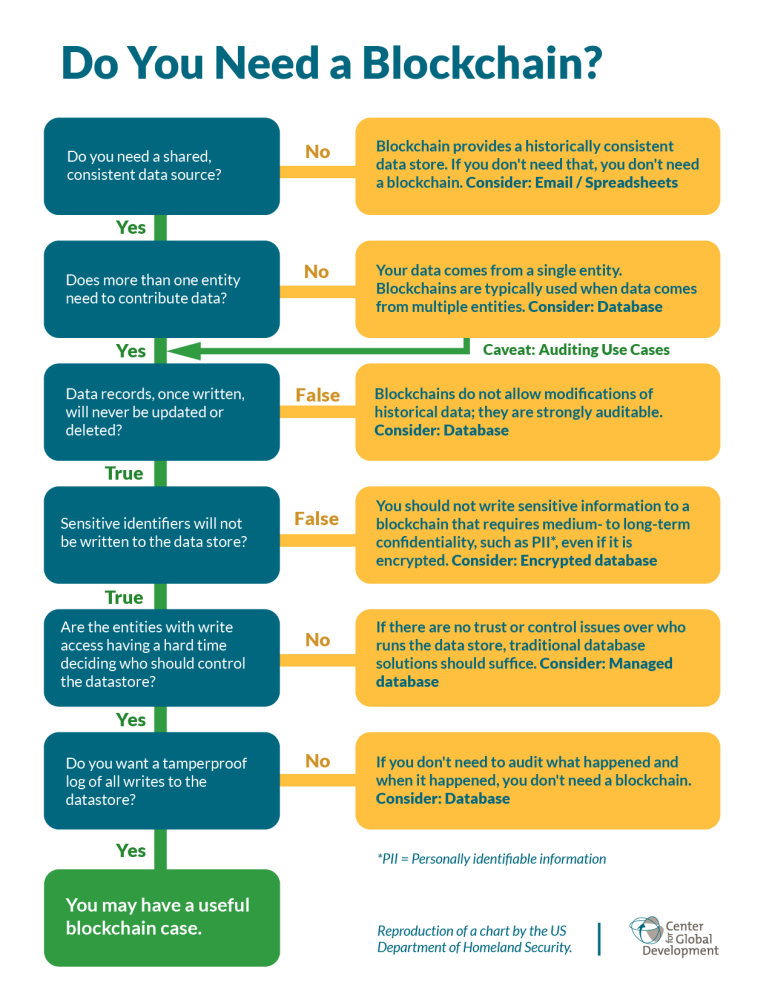

Whether the benefits of using a decentralized model exceed the added cost of complexity ultimately depends on the use case in question. In recent years, a variety of decision models have been created to help guide the process of weighing these tradeoffs (a recent iteration, this one produced by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, is presented in Figure 1).[6] In general, these suggest that, in the vast majority of cases, organizations are better off using simpler (i.e., centralized) database models. Below we explore two development use cases through this tradeoffs lens.

Use Case #1: Providing a platform for refugee IDs

1.1 billion people, roughly 1 in every 7 in the world, lack proof of their legal identity. This problem disproportionately affects children and women from rural areas in Africa and Asia, and is even more acute for the world’s more than 21 million refugees.[7] Without legal identification, it can be difficult to access health and education services, open a bank account, get a loan, and vote.[8] Governments have also become increasingly interested in providing digital legal ID, as recent advances in technology have made it easier to do so, and as the share of business conducted online grows.

At the same time, there is growing concern worldwide about the vulnerabilities associated with the storage and use of personal data by governments and companies. Many believe that both problems could be solved by using a self-sovereign identity (SSI) approach to ID. This model aims to shift control to individuals by allowing them to “store their own identity data on their own devices, and provide it efficiently to those who need to validate it, without relying on a central repository of identity data.”[9] Until recently such a solution was technically infeasible, but blockchain technology appears to make it possible.

There is great interest in the development community about whether the SSI model could help to improve the lives of the world’s poorest, with some even suggesting that it could help relieve the migrant crisis.[10] Some of the organizations now exploring the technology’s potential to this end include Microsoft, Accenture, UNHCR, and ID2020. [11] [12]

Under the generic SSI model, individuals use a digital wallet on a blockchain to store certifications from trusted authorities (e.g., banks, credit rating agencies, hospitals, passport authorities) asserting that they possess certain attributes. For example, each person could store the following certified claims in her wallet: “credit rating over 700,” certified by a credit rating agency; “is over 21,” certified by a government; “has blood type B” certified by a hospital. When the user must show that she has certain attributes to service providers (e.g., when she must prove that she is older than 21 to enter a bar; or that she has a credit rating above 700 to obtain a loan), she can share them without sharing any additional personal information.

Storing verified claims on a blockchain create several potential benefits for users. The first is control: SSI could enable a person to manage both who she shares her personal information with and how much information she shares. Such a system could also be more convenient, since it could allow people to provide verified information with the touch of a button rather than having to access and submit a wide variety of documents. Finally, the near-impossibility of tampering with records on a blockchain could provide greater confidence about their authenticity.

Proponents of the model cite several ways that SSI models could improve refugees’ well-being. First, storing ID documents and important records on a blockchain could make it easier for refugees to verify their identity and obtain appropriate services if they relocate (e.g., a refugee who can provide a trusted immunization record could avoid being given the same vaccine in different camps).[13] Using an SSI model could also allow refugees who are unable to obtain a government ID to build a composite identity through multiple claims. Similarly, they could use their digital wallets to store a history of their economic transactions, which would allow them to develop a credit history that could be used to access financing.

While these features are promising, the model also has serious limitations. Most importantly, because the SSI approach continues to rely on trusted third parties—to provide the certifications stored in each person’s digital wallet and store the data on which those claims are based—it does nothing on its own to solve the core challenge of providing foundational IDs. In addition, the portability of IDs generated and stored on a blockchain depends entirely on how many organizations (either on or off the network) are willing accept them. For that reason, getting multiple governments and development organizations to agree on a single SSI approach is a prerequisite to developing an effective model.

The SSI model also introduces complexities that may make it difficult to scale. This includes challenges related to key management. Since a user’s identity is tied to her private/public key pair, a person who loses a key will need to start the identity proofing process from scratch to reestablish their digital identity.[14] The irrevocability of data stored on the blockchain also raises concerns about data privacy, which is crucial when dealing with refugees, who are often politically persecuted. It is therefore important for software developers creating ID solutions to take a “privacy by design” approach.[15]

In sum, while excitement about the SSI approach and the ways it could improve the lives of the world’s most vulnerable people is understandable, the model’s complexity is a major barrier to adoption.

Use Case #2: Managing Health Supply Chains

The World Health Organization estimates that one in ten medical products used in low- and middle-income countries is either substandard or falsified (SF), with most reported cases (42 percent) coming from Africa.[16] This problem stems in part from poor supply chain management, which prevents local health clinics from knowing the provenance of the medical supplies they use. Improving the ability to “track and trace” the movement of medical goods across the supply chain would help to address this problem.

Interest in improving health supply chains is not limited to developing countries. The US Drug Supply Chain Security Act passed in 2013 calls for the development of an electronic, interoperable system to identify and trace the movement of prescription drugs distributed in the country by 2023. The European Union passed similar legislation in 2016. Both initiatives have spurred investment in possible solutions, including blockchain.

Following the lead of companies with large logistical operations like Walmart and Maersk, the pharmaceutical industry is now exploring the technology’s potential for its own supply chains. Over the last year, several initiatives that aim to use blockchain to meet track and trace regulations have been announced, including The MediLedger Project and a collaboration between DHL and Accenture.[17] [18]

The idea of using blockchain technology as a platform for supply chains holds great promise. By providing a single, tamper-resistant ledger on which transactions can be viewed by all actors with appropriate permissions, the technology could reduce many of the frictions and vulnerabilities in existing supply chain networks. Greater visibility over the movement of goods could reduce the costs and time associated with reconciliation, minimize the potential for counterfeiting, expedite recalls, and aid inventory management.

Supply chains also meet many of the criteria set forth in Figure 1 regarding when a blockchain solution may be useful, including the involvement of multiple actors who need both “read” and “write” database access, the desirability of a tamperproof log of transactions, and a potential inability to trust a single actor in the supply chain to store the data. And while the technology cannot fully substitute for trust between supply chain partners (e.g., those at the end of the supply chain must still trust pharmaceutical manufacturers to provide accurate information about the ingredients they use), it can enhance it by providing “a single source of truth” that has been agreed to by all actors on the network.

Recording health supply chain data on a shared ledger could also unlock new capabilities not possible under the current model in which data remains siloed in individual companies. For example, pharmaceutical companies could analyze aggregated data to predict stock-outs before they happen and better monitor disease outbreaks in real-time. Using a blockchain platform in combination with electronic sensors at different stages of the supply chain could also help to monitor and verify that vaccines have been stored at appropriate temperatures.

Perhaps the most critical obstacle to achieving this vision is meeting the pharmaceutical industry’s demand for data privacy. To date, manufacturers and distributors have been unwilling to share commercially sensitive data with one another. Solving this problem requires the use of permissions secured by encryption, which adds a layer of complexity. For example, the company Chronicled (which runs The MediLedger Project) is using zero proof theorems which allow “transactions to be publicly verifiable without having to contain sensitive information.”[19]

Before a blockchain can serve as a supply chain platform, several prerequisites must also be met. The most basic is the need to assign a unique identity (i.e., serial number) to each product in the supply chain through a process called “serialization.” While this process sounds simple, it requires a high degree of coordination around a set of (ideally global) standards. The next step is making sure that all actors on the supply chain have the ability to scan products and make use of the data provided. Most experts believe that establishing industry-wide serialization will take years to complete.[20]

Another necessary prerequisite is a supportive legal environment. Experts in the highly regulated health sector are just beginning to consider how decentralized models fit with the existing legal framework and what reforms might be needed to enable new approaches. To state the obvious, companies are unlikely to use a blockchain-based platform until they have confidence that it meets these regulations. At the same time, policymakers will only pursue reform once they have developed expertise about decentralized models. This again points to the need for patience, as well as education.

Despite these challenges and the likely long period of transition, supply chain management appears to be an area where the benefits provided by blockchain technology could exceed the cost of complexity. Determining this will ultimately depend on information gleaned from conducting pilot projects.

Conclusion

Whether using a decentralized governance model is worth the added cost of complexity depends entirely on the attributes of the case in question. While the costs appear to outweigh the benefits in most instances, there are a few areas in which blockchain technology could help us address longstanding challenges in new and more effective ways.

Given the development community’s interest in exploring the technology, it is important to set a course that allows for effective experimentation and learning. Here are a few suggestions for how to move the discussion forward in a more useful direction:

- Get specific. There is a glut of “blockchain for development” surveys, including this essay, and none are terribly useful.[21] Since blockchain models and the value they provide differ greatly across use cases, analysis should focus on specific applications. This will require pairing sector specialists with technical experts, ideally with a policy person in the mix.[22]

- Get real. Blockchain boosters often exaggerate the technology’s capabilities and overlook hurdles to adoption, leading to unrealistic expectations. Similarly, there is a tendency for blockchain enthusiasts to assume that centralized solutions are always second-best (or worse) and that trust is always lacking. These assumptions should be questioned in every use case.

- Get data (and share it). Blockchain start-ups are often quick to publicize their pilot project “successes,” while failing to provide metrics to support their claims. Without this data, the development community will struggle to determine what approaches are most likely to work and at what cost. Organizations that fund pilot projects should require the start-ups they partner with to collect and report this data.

- Cultivate patience. In many ways, getting the technology right is the easy part. The more difficult challenges involve getting multiple actors to agree to a common set of standards and establishing legal and regulatory compliance. Doing both will require answering complicated questions with little precedent like who owns data stored on a blockchain, who is liable, and what is needed for the data to be accepted by all parties. For this reason, going from pilot to scale will take much longer than is commonly acknowledged. The development community can accelerate this process by conducting more pilots, collecting and sharing more data, and having more conversations about what an enabling regulatory framework could look like.

I am grateful to the following people for taking the time to review this paper and provide their insights: Susan David Carevic, Alan Gelb, Rachel Alexandra Halsema, Paul Nelson, Stela Mocan, John Polcari, and Aaron Sparks.

[1] Nelson, Paul. USAID. “A Primer on Blockchain.” https://www.usaid.gov/digital-development/digital-finance/blockchain-primer

[2] Blockchain Company and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) “The Future is Decentralized. Blockchains, Distributed Ledgers, & the Future of Sustainable Development.” 2018. https://www.blockchain.com/whitepaper/index.html

[3] Steve Wilson makes this point in a 2017 speech here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UH5-wvfVph4&feature=youtu.be&t=348

[4] Samman, George. “The Trend Towards Blockchain Privacy: Zero Knowledge Proofs.” Coindesk. September 12, 2016.

[5] Graglia, J. Michael and Christopher Mellon. “Blockchain and Property in 2018: At the End of the Beginning.” Working Paper for 2018 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty, March 19–23, 2018.

[6] Meunier, Sebastien. “When do you need blockchain? Decision models.” Medium, August 4, 2016 https://medium.com/@sbmeunier/when-do-you-need-blockchain-decision-models-a5c40e7c9ba1

[7] World Bank, ID4D. Identification for Development: Making Everyone Count. May 4, 2017. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/332831455818663406/WorldBank-Brochure-ID4D-021616.pdf

[8]World Bank. 2018. Principles on identification for sustainable development: toward the digital age (English). Washington, DC: World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/213581486378184357/Principles-on-identification-for-sustainable-development-toward-the-digital-age

[9] Lewis, Antony. “A gentle introduction to self-sovereign identity.” Bits On Blocks, May 17, 2017. https://bitsonblocks.net/2017/05/17/a-gentle-introduction-to-self-sovereign-identity/

[10] Warden, Staci. “Can Bitcoin Technology Solve the Migrant Crisis?” Wall Street Journal, June 8, 2016. https://www.wsj.com/articles/can-bitcoin-technology-solve-the-migrant-crisis-1465395474

[11] Accenture. “Accenture, Microsoft Create Blockchain Solution to Support ID2020.” June 19, 2017. https://newsroom.accenture.com/news/accenture-microsoft-create-blockchain-solution-to-support-id2020.htm

[13] Thanks to Susan David Carevic, IT Officer, World Bank Group, for providing this example.

[14] Hall, Blake. “5 Identity Problems Blockchain Doesn’t Solve.” Medium, July 6, 2017. https://medium.com/@blake_hall/5-identity-problems-blockchain-doesnt-solve-ed4badb94398

[16] World Health Organization. “1 in 10 medical products in developing countries is substandard or falsified.” Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. November 28, 2017. http://www.who.int/en/news-room/detail/28-11-2017-1-in-10-medical-products-in-developing-countries-is-substandard-or-falsified

[17] Accenture. “DHL and Accenture Unlock the Power of Blockchain in Logistics.” March 12, 2018. https://newsroom.accenture.com/news/dhl-and-accenture-unlock-the-power-of-blockchain-in-logistics.htm

[18] MediLedger. https://www.mediledger.com/

[19] MediLedger. “The Mediledger Project: 2017 Progress Report.” MediLedger. February 2018. https://uploads-ssl.webflow.com/59f37d05831e85000160b9b4/5aaadbf85eb6cd21e9f0a73b_MediLedger%202017%20Progress%20Report.pdf

[20] Whyte, Joe. “Pharmaceutical Serialization: An Implementation Guide.” Rockwell Automation. October 2017. http://literature.rockwellautomation.com/idc/groups/literature/documents/wp/lifesc-wp001_-en-p.pdf

[21] There are of course exceptions. Two of the better surveys are: Zambrano, Raul. “Blockchain: Unpacking the disruptive potential of blockchain technology for human development.” International Development Research Centre. August 2017. https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/bitstream/handle/10625/56662/IDL-56662.pdf . And: United States Agency for International Development. “Primer on Blockchain.” Paul Nelson. Washington: United States Agency for International Development, 2018. https://www.usaid.gov/digital-development/digital-finance/blockchain-primer

[22] Thanks to Rachel Alexandra Halsema, IT Officer, World Bank Group, for emphasizing this point.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.