Recommended

Frequent efforts to revise the official development assistance (ODA) accounting rules have raised important questions about the integrity and relevance of what currently “counts” as ODA spending. In this note, we outline a brief history of the evolution of the ODA accounting rules to date, highlighting how – and why – the ODA concept has changed since it emerged in 1969. Doing so provides a starting point for considering whether the current concept of ODA remains “fit for purpose” and whether, or how, the concept could reform to better meet current needs.

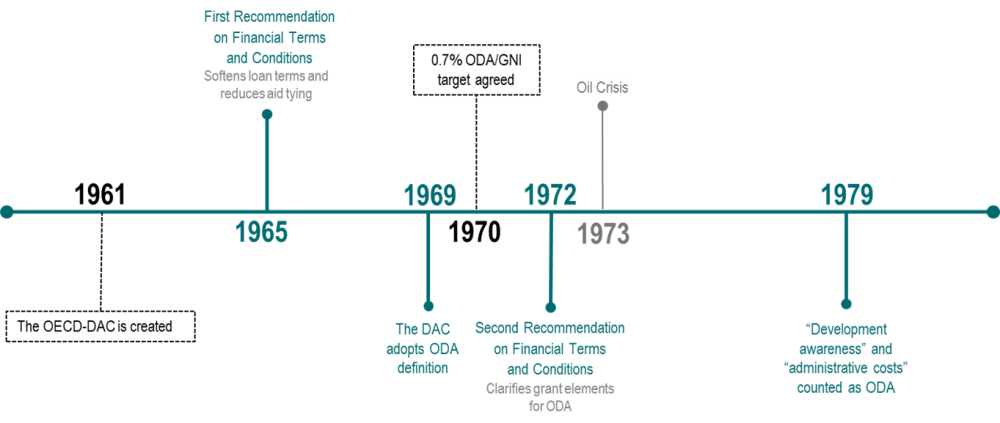

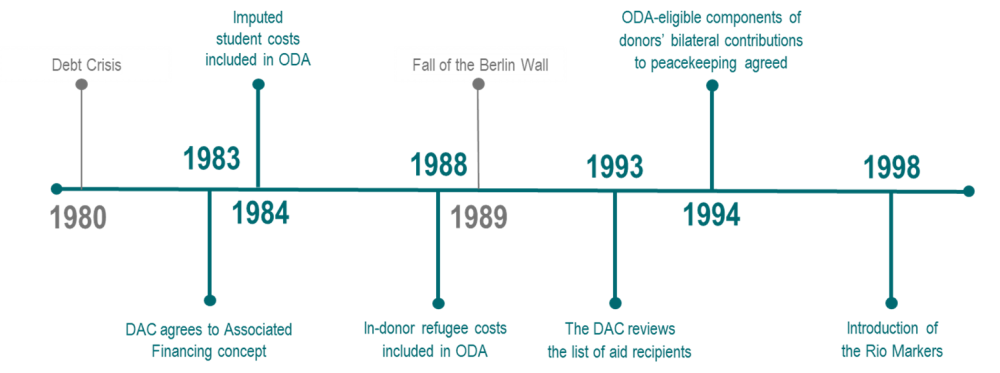

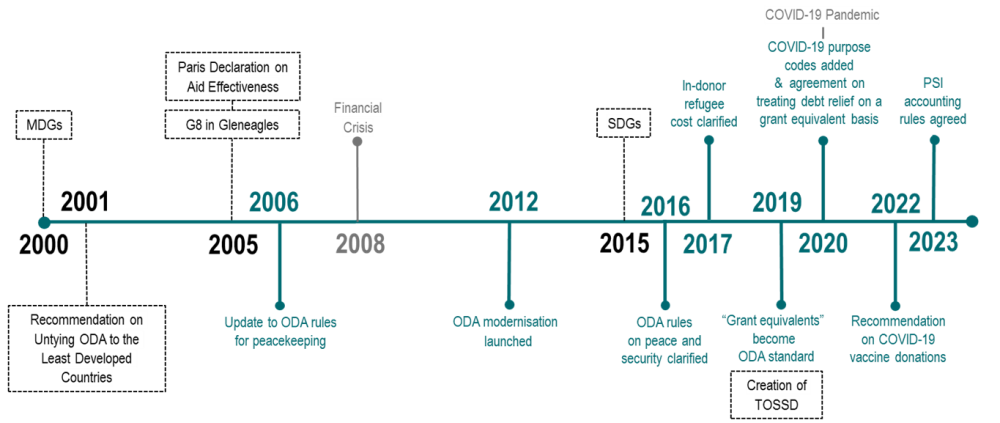

The note proceeds chronologically, with each section corresponding to a unique period in the ODA evolution timeline.

1960-1979: The creation of official development assistance

The concept of ODA was formalized in 1969, as members of the newly created OECD-DAC sought to bring consistency and clarity to growing flows of “development assistance.” Emerging in the aftermath of the Second World War, early development flows were largely ungoverned, lacking both an agreed definition of the purposes or types of finance that counted as “assistance”, as well as a standard metric for measuring the volumes of flows provided.[i] By the 1960s, the growing importance of development cooperation as an ongoing function of provider countries, partly to “confront the ‘Sino-Soviet economic offensive,’”[ii] necessitated the creation of the DAC as a space to consolidate a community of “Western” donors to discuss and generate standards for development practice and finance. Defining what “counts” as development assistance was high on the DAC’s early agenda, with initial discussions – which resulted in the First DAC Recommendation on Financial Terms and Conditions (1965) – focused on defining the terms and concessionality of development loans, before formally agreeing to the new concept of ODA in 1969.[iii] This definition distinguished ODA from other development flows based on concessionality and development-oriented motivation,[iv] as “the flow of grants and soft loans from the donor’s public sector for developmental purposes, net of repayments of capital, but disregarding interest.”[v]

The years that followed saw several efforts to refine the new ODA definition. This included decisions made during the 1972 “Second DAC Recommendation on Financial Terms and Conditions”, which added a “minimum level of grant element” that would be needed for financing to qualify as ODA.[vi] This decision stemmed from the recognition that the existing terms lacked a precise numerical test to exclude non-concessional loans from being categorized as ODA. While the DAC Statistics Group produced a series of simulations to assess the effect of different concessionality thresholds, they settled on 25% for pragmatic reasons – it was the highest threshold with the fewest repercussions on the ability for countries to meet the 1969 definition and on commitment volumes.[vii] Moreover, the DAC began to clarify the actions that “count” as ODA soon after the 1969 decision. In 1971, the DAC reached an agreement in principle to include administrative costs of operating development programmes as ODA, with further decisions made in 1974 and 1979.[viii] Similarly, following a surge in interest in promoting development activities at home in the years following the adoption of the 0.7% ODA/GNI spending target (agreed in 1970), the DAC also agreed to include “development awareness” activities in provider countries as ODA eligible in 1979.[ix]

1980-1999: Revising what “counts” under ODA

Throughout the 1980s, changes to the ODA accounting rules responded to shifting economic and political circumstances which followed the 1980s debt crisis. Notably, the global economic slow-down and subsequent wave of neoliberal politics in donor countries raised concern that ODA was increasingly being used to “gain commercial advantage” for provider countries,[i] including through tying and subsidizing export credits in a manner that threatened to “water down” the ODA concept.[ii] In response, the DAC agreed to a new statistical concept of “associated financing”, which aimed to safeguard the “development orientation” of ODA by stipulating that only the grant or soft loan portion of flows could be counted as ODA when concessional resources are combined with other official flows, export credits, or other non-concessional transactions.[iii] The following year, imputed student costs were added to ODA accounting rules, despite being previously dismissed by the DAC on the understanding that in most cases “the intake of students from developing countries was a response to general political considerations or policies related to the education system, rather than a specific concern to foster development.”[iv] Indeed, by the mid-1980s, declining public funding for higher education incentivized the recruitment of foreign students – partly through development assistance programs – with higher education constituencies pushing for such reform.[v] In 1988, the DAC agreed to rules for reporting the first year of costs associated with refugee hosting as ODA. The decision came despite reservations concerning the “developmental motivation” of such spending – with some questioning whether the economic benefit of refugee hosting is greater for the country of origin or the host country[vi] – and leading some donors to initially choose not to report in-donor refugee costs.[vii]

The 1990s saw only minor changes to ODA accounting related to the inclusion of bilateral contributions to peacekeeping, which followed an expansion of peacekeeping missions in the years after the end of the Cold War.[viii] Notably, DAC members agreed to count bilateral contributions on the proviso that: 1) amounts claimed were net of UN compensation and “normal costs” of keeping forces at home, and 2) only select costs related to governance and democracy promotion (elections, training police, human rights promotion) or the “demobilization of soldier, disposal of weapons and demining” could be counted.[ix] While the ODA rules remained otherwise unchanged, the decade saw two peripheral changes to ODA eligibility and monitoring. First, the dissolution of the former Soviet Union prompted a 1992 review of the DAC recipient list to add new recipient countries (e.g. Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan) and recognize a new category of “countries in transition” – including high-income countries such as Estonia, Poland, and Slovak Republic – which could receive “official aid”, but not ODA.[x] Second, to help monitor commitments made during the 1992 UN Rio Earth Summit, the DAC introduced the “Rio markers” in 1998 to monitor member’s development finance activity in relation to the objectives of the Rio Conventions on biodiversity, climate change, and diversification.[xi]

2000-2024: The expansion and modernization of ODA

The 2000s similarly saw only minor adjustments to the ODA rules – namely related to peacekeeping – at a time when the focus was primarily on increasing the quantity and quality of ODA to meet the new Millennium Development Goals. Specifically, reforms to ODA accounting included small changes to reporting directives for “technical cooperation and civilian support to security systems reform” in the aftermath of 9/11,[i] and a 2006 agreement to count 6% of multilateral contributions to UN peacekeeping as ODA, building on reforms made in the prior decade.[ii] Perhaps more notably, the 2000s saw clear advances towards better defining ODA effectiveness with the 2001 adoption of the Recommendation on Untying ODA to the Least Developed Countries[iii] and the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness. Despite few changes to the ODA definition throughout the decade, concerns over prior reforms to ODA accounting had prompted long running efforts – beginning in 1996 – to develop a new measure of the subset of ODA over which recipients have significant control.[iv] This measure, called “country programmable aid” (CPA), was finalized in 2007. Indeed, in light of commitments to expand the quantity of ODA – including at key moments such as the first Financing for Development Summit and the G8 in Gleneagles – CPA was finalized at a time when DAC members faced growing incentives to broaden ODA accounting to meet new quantity targets.

During the 2010s, the ODA accounting rules underwent substantial reform as part of the DAC’s efforts to “modernise” ODA alongside major changes in the development landscape. First, responding in part to new financial realities – namely, that low interest rates in the wake of the financial crisis meant that even non-concessional loans met the ODA tests (i.e. 25% grant element and 10% discount rate) – and donor incentives to “count” loans made at market rates as ODA to meet volume commitments made in the prior decade, a key aim of the modernisation agenda was to correct for the overcounting of ODA-eligible loans.[v] To do so, the DAC agreed to “overhaul” the ODA concept during its 2014 High-Level Meeting, deciding that from 2019 onwards, headline ODA figures would be measured as “grant equivalents” rather than “net flows”.[vi] Given that the grant equivalent system would also have implications for how providers reported debt relief of ODA loans, in 2020, the DAC agreed to similarly report debt relief on a grant equivalent basis.[vii] While the adoption of the grant equivalent approach aimed to correct for overcounting, the approach has been widely criticised for overestimating the “true value” of ODA loans,[viii] and the potential to double-count “risk” in the application to debt relief.[ix] Second, the combination of tightening public budgets in the aftermath of the financial crisis, and pressures to use ODA to leverage private finance in efforts to scale-up funding for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) led DAC members to explore methods of including more investments in private sector development as ODA. While negotiations on “private sector instruments” (PSIs) initially stalled, in 2023, the DAC agreed to a method for counting either capital increases to institutions that extend PSI (namely, donor development finance institutions), or individual activities under a range of PSI modalities (i.e. loans, equities, guarantees, mezzanine finance, etc.) as ODA.[x] The PSI rules similarly sparked concern, with some arguing that the new rules could functionally allow donors to “score ODA for their commercially viable investments”.[xi] Alongside these changes to ODA accounting, recognition that ODA measurement captured only part of the development finance story, particularly alongside calls for greater private sector contributions to sustainable development and in light of growing flows from countries beyond the DAC, sparked efforts to create a new statistical measure – called Total Official Support for Sustainable Development (TOSSD) – to capture a wider array of resources available to promote sustainable development in developing countries.[xii]

While the 2010s also saw minor revisions to eligibility and accounting rules related to peace and security[xiii] and in-donor refugee costs,[xiv] as well as the creation of a new purpose code for migration in the wake of the Syrian civil war and growing refugee flows,[xv] further questions about ODA accounting emerged in the early 2020s with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. In response to resources mobilized to counter the impact of COVID-19, DAC members agreed to introduce a new purpose code for tracking COVID-19-related activities in 2020.[xvi] The following year, the DAC issued guidance on how to count COVID-19 vaccines donations as ODA-eligible activities, recommending that members count donated doses using the price of USD 6.72 per dose.[xvii] The decision to count vaccine donations as part of ODA budgets was controversial, with some members arguing that excess vaccine donations should not be considered ODA eligible.[xviii]

Is today’s ODA a credible measure of development effort?

The evolution of the ODA accounting rules highlights a series of sometimes contested decisions that raise questions about ODA’s continued credibility as a measure of solidaristic finance to support the welfare and development of lower-income countries. While the initial conceptualization of ODA stressed “development-orientation” and “concessional” characteristics as defining factors, changes to both the activities that “count” as ODA – such as the inclusion of imputed student costs, in-donor refugee spending, and surplus COVID-19 vaccines – and how ODA is measured – through the introduction of grant equivalents – have raised concerns that both guiding principles have been eroded over time. On “development orientation”, the development value to lower-income countries of finance which remains in donor countries (e.g. in-donor refugee spending, student costs) has been an ongoing source of contention, especially when spikes in in-donor spending – including in the wake of crises in Ukraine and Palestine – displaces other cross-border flows (i.e. when overall ODA budgets remain flat).[xix] Similarly, the recent ODA modernization process raised a series of concerns regarding the concessionality pillar of ODA reporting, with some arguing that the discount rates applied to ODA loans, debt relief, and PSI, “are so high that they almost guarantee that every conceivable loan or guarantee, no matter how profitable, will score positive ODA”.[xx]

Part of the challenge is undoubtedly linked to the DAC-led nature of ODA decision-making, which means that the accounting rules necessarily prioritize the incentives of providers without seeking input from partner countries about whether changes would be considerable acceptable – or beneficial – from their perspective.[xxi] As many have pointed out, the result is a system where DAC member interests dominate ODA rule-making, leading to a majority of changes that expand the activities which can be counted as ODA (see Annex 1), without necessarily growing the finance that delivers value for partner countries. Indeed, the evolution of ODA highlights a persistent trade-off between accounting changes aimed at increasing the quantity of ODA, several of which occur around major volume commitments, and the dilution of ODA's quality – or integrity – in terms of the development value that funding offers to partner countries. Going forward, key questions about the future of ODA will likely need to consider not only technical questions about what should count in the ODA statistic, but also whether ODA governance systems should be reformed to allow for more participatory decision-making that also considers the preferences of recipient countries.

Conclusion

In a shifting development landscape, where donors are asked to respond to complex interrelated crises, often through ODA, DAC members will likely face additional pressures to expand what “counts” under ODA reporting. However, deciding whether and how ODA should reform, will likely depend on first-order questions related to the role that ODA is expected to play alongside other sources of development finance, and whether the current accounting rules leave ODA well positioned to achieve its intended aims. While these questions are still open for debate, they remain critical for informing the future of ODA and the changes necessary to ensure its continued relevance and credibility.

Sources

Bracho, Gerado. “Diplomacy by Stealth and Pressure: The Creation of the Development Assistance Group (and the OECD) in 51 days.” In Origins, Evolution, and Future of Global Development Cooperation: The Role of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) edited by Gerardo Bracho, Richard Carey, William Hynes, Stephan Klingebiel, Alexandra Trzeciak-Duval, 149-246. Bonn: Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik, 2021. https://www.idos-research.de/uploads/media/Study_104.pdf

Bracho, Gerardo, Richard H. Carey, William Hynes, Stephan Klingebiel and Alexandra Trzeciak-Duval. “Concluding Thoughts.” In Origins, Evolution, and Future of Global Development Cooperation: The Role of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) edited by Gerardo Bracho, Richard Carey, William Hynes, Stephan Klingebiel, Alexandra Trzeciak-Duval, 578-589. Bonn: Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), 2021. https://www.idos-research.de/uploads/media/Study_104.pdf

Carey, Richard. “Development, development cooperation, and the DAC: epistemologies and ambiguities.” In Origins, Evolution, and Future of Global Development Cooperation: The Role of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) edited by Gerardo Bracho, Richard Carey, William Hynes, Stephan Klingebiel, Alexandra Trzeciak-Duval, 11-72. Bonn: Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik, 2021. https://www.idos-research.de/uploads/media/Study_104.pdf

Chadwick, Vince. “Sweden Pulls $1B in Foreign Aid for Ukrainian Refugees at Home.” Devex, May 5, 2022. https://www.devex.com/news/sweden-pulls-1b-in-foreign-aid-for-ukrainian-refugees-at-home-103164.

Chadwick, Vince. “US, Netherlands unconvinced on aid eligibility of surplus vax donations.” Devex, December 23, 2021. https://www.devex.com/news/us-netherlands-unconvinced-on-aid-eligibility-of-surplus-vax-donations-102364.

Craviotto, Nerea. “Debt Relief and ODA.” The Reality of Aid Network. N.d. Accessed May 2024. https://realityofaid.org/reality-check/blogs/debt-relief-and-oda/.

Führer, Helmut. The Story of Official Development Assistance. Paris: OECD Publishing, 1996. https://www.oecd.org/dac/1896816.pdf.

Hynes, William and Simon Scott. The Evolution of Official Development Assistance: Achievements, Criticisms and a Way Forward. OECD Development Co-operation Working Papers 12. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k3v1dv3f024-en.

Hynes, William, and Simon Scott. “The Evolution of Aid Statistics: A Complex and Continuing Challenge.” In Origins, Evolution, and Future of Global Development Cooperation: The Role of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) edited by Gerardo Bracho, Richard Carey, William Hynes, Stephan Klingebiel, Alexandra Trzeciak-Duval, 248-271. Bonn: Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik, 2021. https://www.idos-research.de/uploads/media/Study_104.pdf

Knoll, Anna and Andrew Sheriff. Making Waves: Implications of The Irregular Migration and Refugee Situation on Official Development Assistance Spending and Practices in Europe. Stokcholm: Expertgruppen för biståndsanalys, 2017. https://eba.se/en/reports/making-waves-implications-of-the-irregular-migration-and-refugee-situation-on-official-development-assistance-spending-and-practices-in-europe-2/5239/

ODA Reform. “Overcounting the ODA in Loans.” Accessed May 10, 2024. https://www.odareform.org/oda-loans

ODA Reform. “The need to reform the governance of ODA rules.” Accessed May 10, 2024. https://www.odareform.org/oda-governance

OECD. DAC in Dates: The History of OECD’s Development Assistance Committee. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2006. https://www.oecd.org/dac/1896808.pdf

OECD. “Frequently Asked Questions on The Oda Eligibility Of Covid-19 Related Activities.” Updated December 2023. Accessed May 2024. https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/faqs-oda-eligibility-of-covid-19-related-activities.pdf.

OECD. “Frequently asked questions: the modernisation of official development assistance (ODA).” Development Co-operation Directorate. Accessed May 2024. https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/oda-modernisation-faq.htm

OECD. “In-donor refugee costs in official development assistance (ODA).” Development Co-operation Directorate. Accessed May 8, 2024. https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/refugee-costs-oda.htm.

OECD. “The Modernisation of Official Development Assistance.” Accessed March 10, 2024. https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/modernisation-dac-statistical-system.htm

OECD. OECD DAC Rio Markers for Climate Handbook. Paris: OECD Publishing, n.d., https://www.oecd.org/dac/environment-development/Revised%20climate%20marker%20handbook_FINAL.pdf

OECD. Working Party on Development Finance Statistics. “Proposed New Purpose Code For ‘Facilitation Of Orderly, Safe, Regular And Responsible Migration And Mobility’.” DCD/DAC/STAT (2018)23/REV3. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2018. https://one.oecd.org/document/DCD/DAC/STAT(2018)23/REV3/en/pdf

Ritchie, Euan. “Measuring ODA: Four Strange Features of the New DAC Debt Relief Rules.” CGD Blog, September 2020. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/measuring-oda-four-strange-features-new-dac-debt-relief-rules.

Ritchie, Euan. Mismeasuring ODA— How Risky Actually Are Aid Loans?, CGD Note , November 2020. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/mismeasuring-oda-how-risky-actually-are-aid-loans-0.

Scott, Simon. “Making Nonsense of Aid Measurement.” Development Today, January,2024. https://www.development-today.com/archive/2024/dt-1-2024/making-nonsense-of-aid-measurement.

Scott, Simon. The Accidental Birth of ‘Official Development Assistance’. OECD Development Co-operation Working Papers 24. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2015. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/5jrs552w8736-en.pdf?expires=1709718778&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=019E655EBF741F239CC1DA21E0D077DF.

Scott, Simon. “The Ongoing Debate on the Reform of the Definition of Official Development Assistance.” Brookings, November 18, 2019. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-ongoing-debate-on-the-reform-of-the-definition-of-official-development-assistance

United Nations. “Peace and Security.” Accessed May 13, 2024. https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/peace-and-security

Weiler, Hans N. Aid for Education: The Political Economy of International Cooperation in Educational Development. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre, 1983. https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/eb69434c-937d-4ec5-a316-bba2336e1181/content.

Annex I: Summary of major reforms to ODA and impact on accounting

|

Year |

Change |

Impact on ODA accounting |

|---|---|---|

|

1969 |

First ODA definition |

N/A |

|

1972 |

Tightening of ODA definition: to qualify as ODA, official loans will need grant element of 25% and discount rate of 10% per year |

Reduces total ODA |

|

1979 |

Development awareness and administrative costs counted as ODA |

Increases total ODA |

|

1984 |

Imputed student costs included in ODA |

Increases total ODA |

|

1988 |

In-donor refugee costs included in ODA |

Increases total ODA |

|

1993 |

DAC list of ODA recipients revised to exclude high-income countries |

Reduces total ODA |

|

1994 |

ODA-eligible components of donors’ bilateral contributions to peacekeeping agreed. |

Increases total ODA |

|

2006 |

Agreement on how DAC members’ multilateral contributions to UN peacekeeping |

Increases total ODA |

|

2016 |

ODA rules on peace and security clarified |

Increases total ODA |

|

2017 |

In-donor refugee costs clarified |

Reduces total ODA |

|

2019 |

Grant equivalent methodology becomes standard |

Reduces total ODA |

|

2020 |

New purpose codes for COVID-19 related activities agreed & the DAC reached a consensus on the treatment of debt relief on a grant equivalent basis |

Increases total ODA |

|

2022 |

Guidance for counting vaccine donations issued |

Increases total ODA |

|

2023 |

Private Sector Investment reporting rules agreed |

Increases total ODA |

Source: Adapted from OECD, “Measuring Aid: 50 Years of DAC Statistics 1961-2011” (Paris: OECD, 2011), available from: https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/MeasuringAid50yearsDACStats.pdf

[i] Hynes and Scott, “The Evolution of Aid Statistics,” 260.

[ii] Ibid

[iii] While the issue of untying had been a concern for the DAC since its formation in the 1960s, strong opposition from various delegates at different negotiation rounds meant that it took 30 years for agreement to be reached. See: Richard Carey, “Development, development cooperation, and the DAC: epistemologies and ambiguities,” in Origins, Evolution, and Future of Global Development Cooperation: The Role of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC), edited by Gerardo Bracho et al. (Bonn: Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik, 2021), 25, https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/243086/1/1772133620.pdf

[iv] Ibid, 258.

[v] Hynes and Scott, “The Evolution of Aid Statistics,” 263-264; “Frequently asked questions: the modernisation of official development assistance (ODA),” OECD, accessed May 2024, https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/oda-modernisation-faq.htm

[vi] Hynes and Scott, “The Evolution of Aid Statistics,” 265.

[vii]“The modernisation of official development assistance (ODA),” OECD, accessed March 10, 2024, https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/modernisation-dac-statistical-system.htm#:~:text=The%20grant%20equivalent%20is%20the,the%20amount%20of%20money%20extended. Some have noted that changes to the debt relief rules could lead to double counting, as rescheduled or cancelled loans could already have been counted in ODA figures at the time of issue (see Nerea Craviotto, “Debt relief and ODA”, The Reality of Aid Network, n.d., accessed May 2024, https://realityofaid.org/reality-check/blogs/debt-relief-and-oda/)

[viii] Euan Ritchie, Mismeasuring ODA— How Risky Actually Are Aid Loans?, CGD Note (London: Center for Global Development, 2020), https://www.cgdev.org/publication/mismeasuring-oda-how-risky-actually-are-aid-loans-0; “Overcounting the ODA in Loans,” ODA Reform, accessed May 10, 2024, https://www.odareform.org/oda-loans

[ix] Euan Ritchie, “Measuring ODA: Four Strange Features of the New DAC Debt Relief Rules,” CGD Blogs, September 2020, https://www.cgdev.org/blog/measuring-oda-four-strange-features-new-dac-debt-relief-rules

[x] Simon Scott, “The ongoing debate on the reform of the definition of Official Development Assistance”, Brookings, November 18, 2019. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-ongoing-debate-on-the-reform-of-the-definition-of-official-development-assistance

[xi] Simon Scott, “Making nonsense of aid measurement,” Development Today, January 4, 2024, https://www.development-today.com/archive/2024/dt-1-2024/making-nonsense-of-aid-measurement

[xii] Hynes and Scott, “The Evolution of Aid Statistics,” 262; “What is TOSSD”, TOSSD, accessed May 2024, https://www.tossd.org/what-is-tossd/

[xiii] Namely, agreeing to six ODA eligible security items including: “(1) management of security expenditure; (2) enhancing civil society’s role in the security system; (3) child soldiers; (4) security system reform; (5) civilian peace building, conflict prevention and conflict resolution; and (6) small arms and light weapons” (see Bracho et al. p. 410).

[xiv] Including clarifying the meaning of “refugee” and different categories of refugee, specifying the twelve-month rule, and defining eligibility of specific cost items (see OECD, 2017). OECD, “In donor refugee costs in ODA,” accessed May 2024. https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=IN-DONOR_REFUGEE_COSTS#:~:text=ODA%20in%2Ddonor%20refugee%20costs,on%20in%2Ddonor%20refugee%20costs

[xv] “The Modernisation of official development assistance (ODA), OECD, accessed May 2024, https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/modernisation-dac-statistical-system.htm; DAC Working Party on Development Finance Statistics,

“Proposed New Purpose Code For “Facilitation of Orderly, Safe, Regular and Responsible Migration and Mobility,” DCD/DAC/STAT (2018)23/REV3, May 2018. https://one.oecd.org/document/DCD/DAC/STAT(2018)23/REV3/en/pdf

[xvi] OECD, “Frequently Asked Questions on the ODA Eligibility of Covid-19 Related Activities, “updated December 2023. https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/faqs-oda-eligibility-of-covid-19-related-activities.pdf;

[xvii] For more details see: DAC Working Party on Development Finance Statistics, “Valuation of donations of excess COVID-19 vaccine doses to developing countries in ODA – update for 2022 donations,” DCD/DAC/STAT(2022)33, 2022, https://one.oecd.org/document/DCD/DAC/STAT(2022)33/en/pdf

[xviii]Vince Chadwick, “US, Netherlands unconvinced on aid eligibility of surplus vax donations,” Devex, December 23, 2021, https://www.devex.com/news/us-netherlands-unconvinced-on-aid-eligibility-of-surplus-vax-donations-102364

[xix] As was recently the case in Sweden, for instance, see Vince Chadwick, “Sweden pulls $1B in foreign aid for Ukrainian refugees at home,” Devex, 2022, https://www.devex.com/news/sweden-pulls-1b-in-foreign-aid-for-ukrainian-refugees-at-home-103164;

[xx] Scott, “Making nonsense of aid measurement.”

[xxi] “The need to reform the governance of ODA rules”, ODA Reform, accessed May 2024, https://www.odareform.org/oda-governance

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.

Image credit for social media/web: Dilok / Adobe Stock