Recommended

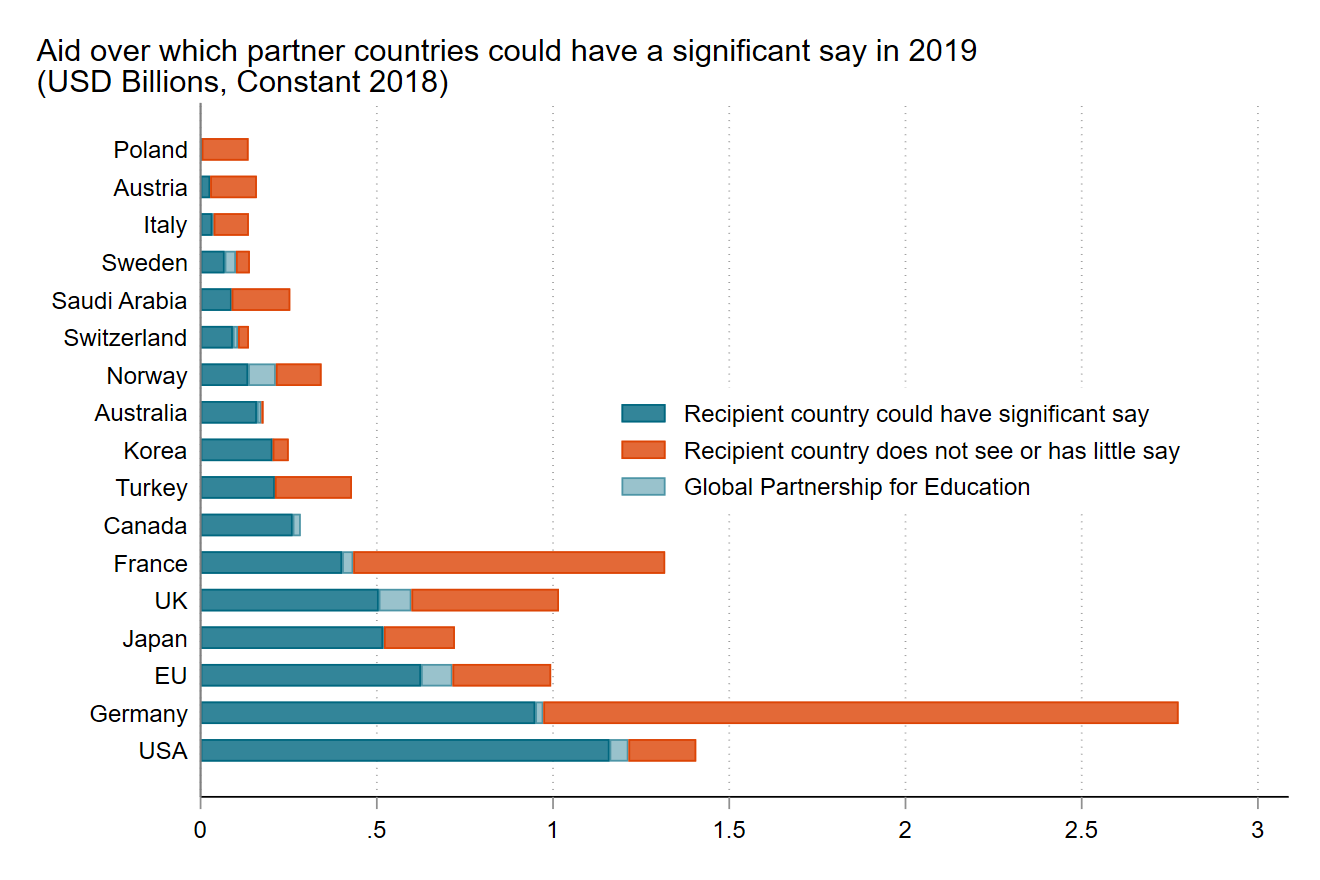

At a recent education conference, experts took turns identifying the common education interventions they’d throw in the trash if they could! Vouchers for private schools, donor interference in education systems, and the artificial link between children’s age and the curriculum they’re taught were all floated. But what about providing training for teachers on the job?

Teacher professional development (PD) is a catch-all term for activities that seek to boost teachers’ skills once they’re already working in the profession, including everything from focused coaching by a more experienced teacher to sitting in a hotel ballroom watching an ironically unengaging PowerPoint presentation about being a more dynamic teacher.

It’s definitely not without issues.

One reviewer of a paper on professional development wrote “I thought [teacher professional development programs] were already discounted thirty years ago”! The reviewer isn’t without basis for their skepticism. One of us evaluated a large-scale teacher PD program in China. Our evaluation was entitled, “Does Teacher Training Actually Work?” The answer, in this case, was no. And a program that trained teachers in Costa Rica on how to work in a more student-centered way actually resulted in lower test scores for students.

But the same can’t be said for all teacher training. A program in Uganda that showed teachers how “to teach students to think like scientists” boosted the students’ pass rates on their primary school leaving exam by about 50 percent! Coaching teachers in South Africa dramatically boosted reading proficiency.

A recent report on the most cost-effective approaches to improve global learning revealed an interesting pattern. While “general skills teacher training” showed little effect on its own, teacher training showed up again and again as a crucial element of the most effective interventions. Among the “good buys” in that report was a nationally implemented literacy program in Kenya that included teacher PD, and a program helping remedial students after school in the Gambia, which relied on regular coaching of para teachers (locally hired, literate and numerate but only briefly trained individuals). And a “review of reviews” of educational research in low- and middle-income countries found that certain types of teacher professional development (individualized, repeated, focused on helping teachers learn a particular tool) were among the most consistently recommended interventions to boost learning.

The reason it’s hard to say whether teacher PD is good or bad is because teacher PD isn’t just one thing. The ineffective PD program in China mentioned above was “overly theoretical” in its content and “rote and passive” in its delivery. The effective coaching program in South Africa involved “ongoing, individualized observation and feedback.” These kinds of differences suggest that whether or not teacher PD is effective depends on both its content and its delivery.

So what distinguishes a good PD program from a bad one?

We dug through dozens of studies of teacher PD programs to try and figure this out. Then we compared the characteristics of good PD programs to the characteristics of large-scale PD programs implemented by many countries. We document our findings in our recently published paper, “Teacher Professional Development around the World: The Gap between Evidence and Practice.” Here are three things we learned.

Lesson 1: The details of teacher PD programs matter, but they often go unreported

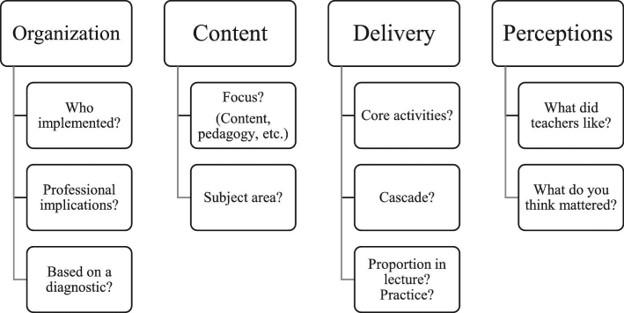

The first thing we did was draw on both theoretical and empirical literature to build an instrument to make it easier to describe teacher PD programs in detail. The instrument—the In-Service Teacher Training Survey Instrument (called the ITTSI and yes, there’s a brief version called the BITTSI)—initially collected data on three categories of characteristics: organizations, content, and delivery (Figure 1). (Later, when we started interviewing the implementers of teacher PD programs, we added one more section: perceptions.)

Figure 1. A survey instrument to facilitate description of teacher professional development programs

Source: Popova et al. 2021

As we read dozens of evaluations of teacher PD programs, we found that on average, only 50 percent of the characteristics covered by our instrument were available in the studies! It’s tough to understand why a program works or doesn’t work if you don’t know much about the program. It’s not that the information didn’t exist; we went on to interview the implementers of many of the programs and were able to boost that number to 98 percent.

If you’re evaluating a teacher PD program and want your study to help the world understand more about what works and what doesn’t, tell us more about the program in the paper (even in an appendix).

Lesson 2: Successful programs and unsuccessful programs are designed differently

Once we got all the information we could about these programs, we compared programs with bigger student learning gains with programs that had smaller student learning gains in order to identify the characteristics of successful programs.

Organization, content, and delivery all make a difference.

First, organization matters: teacher PD programs where participation is linked to some sort of career incentives (like promotion, salary, or status increases) have higher student learning gains. It should come as no surprise that incentives matter, and teachers investing in their own skills is no exception.

Second, content matters: programs that have a specific subject focus are associated with better results. It’s much more effective to teach a teacher better pedagogical skills for math or for science than to teach better pedagogical skills in general.

Third, delivery matters: programs that incorporate lesson enactment into the training deliver better results. It’s not enough for teachers to know some new method in their heads; they need opportunities to practice those methods before they get back to their classrooms. Another element of delivery that came up in interviews with PD program implementers was that follow-up visits to teachers, to observe them and reinforce their new skills, were among the most effective elements of PD programs.

These aren’t causal claims—there aren’t enough studies for us to be confident about exactly which sets of characteristics drive success. But these associations give clues as to what education systems should be trying (and testing) more of.

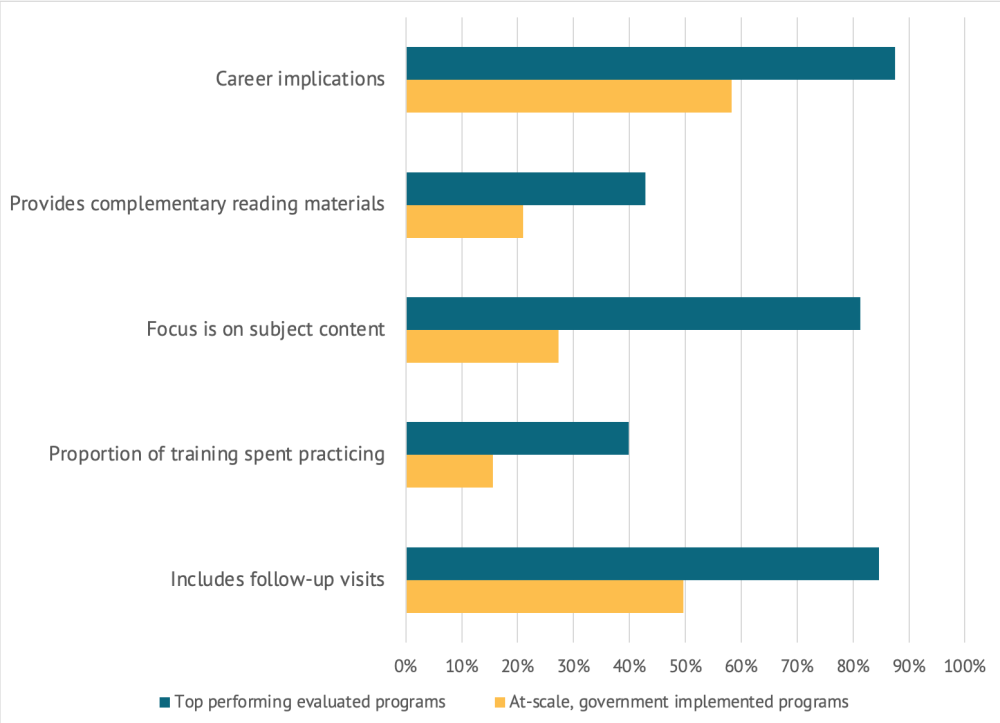

Lesson 3: The teacher training being offered at scale doesn’t have much in common with the training that shows the best impacts

We worked with 14 countries around the world (from Mexico and Moldova to Burkina Faso and Kazakhstan) to identify the characteristics of their major teacher PD programs. Most countries have some sort of teacher PD. But those at-scale, government-implemented PD programs often looked quite different from what evaluations had shown to be successful (Figure 2). At-scale programs were much less likely to include professional incentives to participate in PD, provided fewer opportunities to practice the new skills that teachers were learning, and were less likely to have any sort of follow-up with teachers after the original training. It’s no wonder that national programs like the one evaluated in China proved ineffective or that some experts are ready to toss teacher PD (as they’ve seen it implemented) into the trash.

Figure 2. Differences between top performing evaluated programs and government-implemented at-scale programs

Source: Popova et al. 2021

Of course, doing some of these activities costs more: follow-up visits and complementary reading materials both add to the cost of a program. But others don’t: spending a greater proportion of the training practicing is potentially a cost-neutral design choice. Even those that do cost more invite another possibility: if the budget is fixed, maybe it’s worth providing support to teachers more gradually if it means the support translates into improved student learning rather than wasted time.

Teacher professional development is here to stay. So we may as well do it right.

Even as education systems seek to attract the best candidates and provide them with incentives to do their jobs well, there will always be a need to upgrade the skills of teachers on the job. This will be true as student content is updated, as we learn new, effective ways of teaching, as some teachers forget some of what they know, and as countries rapidly expand secondary education and don’t manage to get every teacher fully up to speed before they enter the classroom.

There are demonstrated, effective ways of boosting teacher skills and practice. It is possible to implement them at scale. Teacher coaching, for example, boosted both teacher practice and student learning in thousands of schools in Peru. The World Bank recently launched a set of resources to support systems in effective teacher PD.

Since teacher professional development is already a line item in most budgets, systems may as well draw on the best evidence to let it deliver on its promise. Both the students and the teachers deserve it.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.