Does a stand-alone Department for International Development have a long-term future? What is the role of DFID in facilitating other British government departments and other UK organizations to assist developing countries? What is its role in influencing the policies of other Whitehall departments?

These questions are being asked not by me but by the UK Parliament’s International Development Committee (terms of reference here). The mere fact that they are raising these questions is interesting (and alarming to some people). But in all the evidence submitted to the inquiry, I haven’t yet found any that supports the idea of merging DFID back in to the Foreign Office.

Alex Evans and I have submitted evidence about DFID’s future role. We contend that to eliminate poverty the development agency of the future is going to have to work more on a broader range of challenges, including fragile states, inclusive growth in middle income countries, and global risks (like climate change). Our full evidence is here.

Because these are long-term processes of structural change, they are problems for which no aid agency has easy solutions. None of these challenges will be solved by aid, though aid can certainly make a contribution.

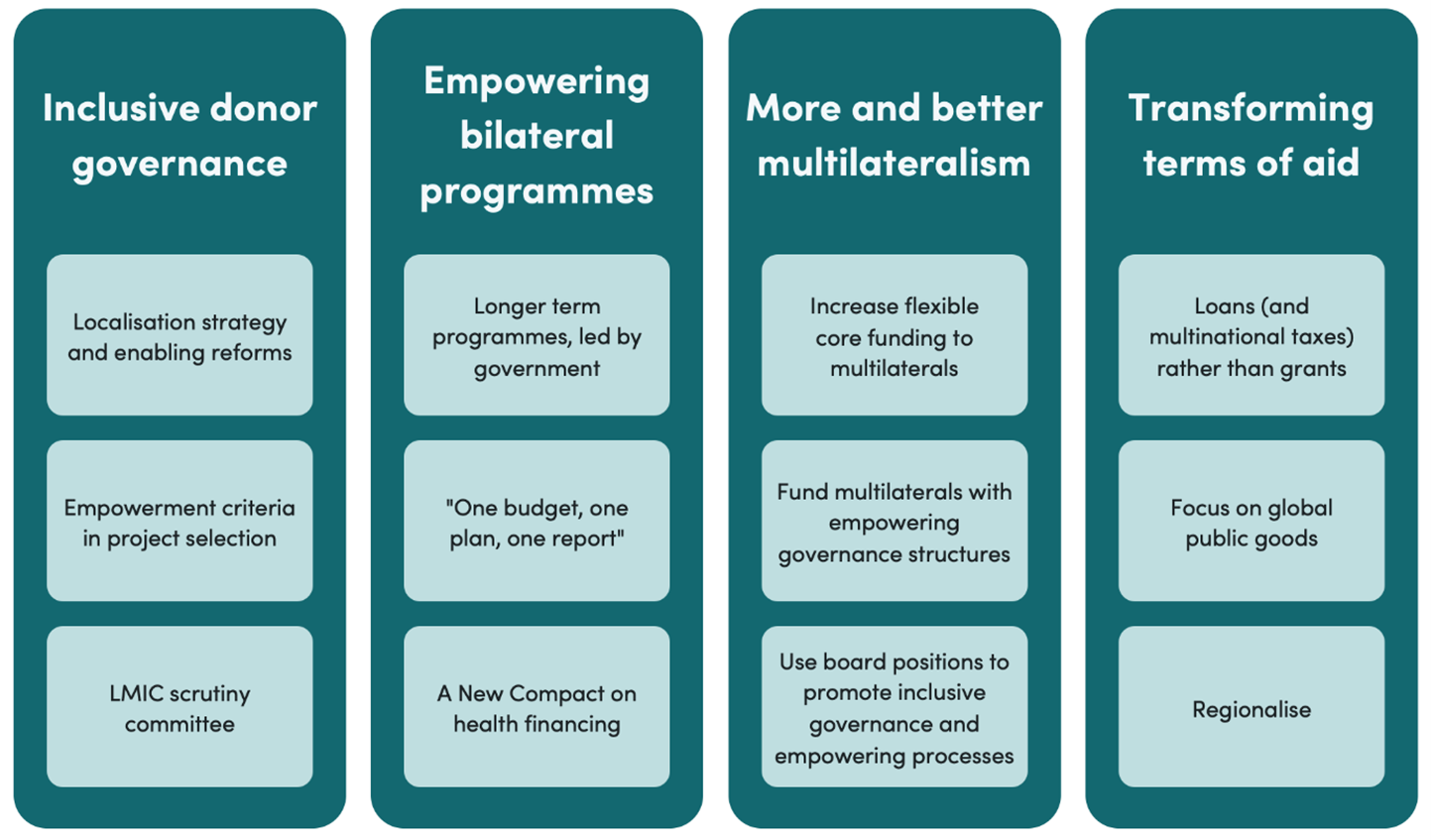

We argue that the development agency of the future will have to focus much more on the “beyond aid” agenda, both abroad and at home. DFID will increasingly need to influence British policy on issues such as international tax cooperation, fighting corruption, opening markets, limiting arms sales, supporting good quality international investment and supply chains, improving the benefits of migration, improving financial regulation, creating and sharing new technologies, and protecting our shared environment and natural resources. DFID will also have to work within government for Britain’s long-term interest in shared global prosperity, effective global institutions and environmental sustainability, and for the public’s concern for the world’s poorest and most marginalized people.

Hardly anyone disputes the need to have the Treasury scrutinize policies within government, with its distinct perspective of protecting the public’s long-term interest in sound public finance from short-term spending pressures, and of protecting the economy from rent-seeking by powerful vested interests. DFID should have an analogous role working with other departments, to protect the long-term interest of British citizens in shared, sustainable global prosperity from short-term political or commercial expediency. Neither the Treasury nor DFID should expect to win every issue they contest; but both have an essential role collaborating with, and if necessary challenging, other government departments.

To have any chance of being able to improve these broader policies it essential that DFID remains separate government department with its own seat in the Cabinet. If it were installed in the Foreign Office, DFID would be relegated to running an aid programme. USAID has almost no influence on broader US policies affecting the developing world. But as my 2005 Working Paper on the history of DFID concluded, it is the mandate – rather than the structure – of development agencies that determines whether they are or can be effective in this ‘beyond aid’ agenda.

If we want DFID to become the development agency of the future, we need to do more than protect its institutional independence. DFID can only operate with the mandate it is given. Ministers, Parliament, and the broader policy community will need to give DFID the political mandate and support it needs to play this critical role, and DFID will need to do more to earn that position.

As well as a memorandum on the future of DFID, I have also submitted evidence (with Theo Talbot) on why “beyond aid” matters for development (which was described in a previous blog post) and (with Petra Krylova) an analysis using CGD’s Commitment to Development Index of how UK policies shape up, how they have changed over time, and how they compare to the policies of their peers, which is the topic for another blog post.

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.