With the threat of antimicrobial resistance on the rise, we are heartened by President Barack Obama’s recent executive order that outlines a national strategy to combat drug resistance, including creation of an inter-agency task force to implement and monitor the plan. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that up to 2 million Americans suffer from antibiotic-resistant infections each year and that 23,000 of them die. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that there were 450,000 new cases of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis globally in 2012, many of them in developing countries. And we know all too well from the Ebola crisis that borders cannot contain dangerous pathogens. Among other things, the strategy calls for improving national surveillance of resistant bacteria and it directs key US agencies to cooperate with the WHO on the global action plan it is developing. Together these actions are important first steps to address drug resistance in the United States and globally.

In support of the national strategy, the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) released a report that recommends increasing investments in stewardship and providing an additional $800 million a year in incentives for drug companies to invest in new antibiotic development. Innovation is certainly important given that the useful life of antibiotics is getting shorter and shorter with the rapid emergence of resistance as highlighted in our 2010 report on drug resistance. But new drugs are also more expensive and it is equally important that we invest in conserving the lifespan of existing drugs.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) took a modest step in that direction last year when it issued voluntary guidance aimed at eliminating the use of antibiotics to promote livestock growth. The livestock industry consumes around 80% of the antibiotics sold in the United States each year. For decades, American producers have administered many of these drugs in the food and water of healthy animals to promote faster growth. But, as noted in a Johns Hopkins University report, regular use of subtherapeutic doses of antibiotics in healthy animals creates prime conditions for the development of drug-resistant microbes.

While a high-level commission funded by the Pew Charitable Trusts recommended phasing out the nontherapeutic use of antibiotics in livestock, the FDA guidance is more modest and has a loophole that could severely undermine its utility. As we pointed out in a blog post last year, the FDA still allows producers to use antibiotics to prevent livestock disease, not just when it is medically required to treat infections. This loophole has been exploited before. In the Netherlands, farmers switched from growth promotion to disease prevention as the rationale for using antibiotics in livestock until the government adopted more stringent regulations. Moreover, since the FDA guidance does not require producers to report which antibiotics they are using in which animals for what purposes, it is virtually impossible to know whether the directive is having the desired effect.

Unfortunately, it does not appear that the new executive order rectifies these problems. The PCAST report merely echoes the FDA guidance on eliminating the use of antibiotics for livestock growth promotion. On the crucial issue of monitoring antibiotic use, the report recommended that the FDA continue to monitor sales to the livestock industry, as it does now, and “where possible,” monitor actual usage. To date, the livestock industry has strongly resisted detailed reporting of this type. As the White House develops the new national strategy to combat antibiotic resistance, we hope more systematic monitoring of antibiotic use in livestock will emerge as part of it. That is the only way to know how big a problem the livestock sector is and what further steps the FDA might need take to address it.

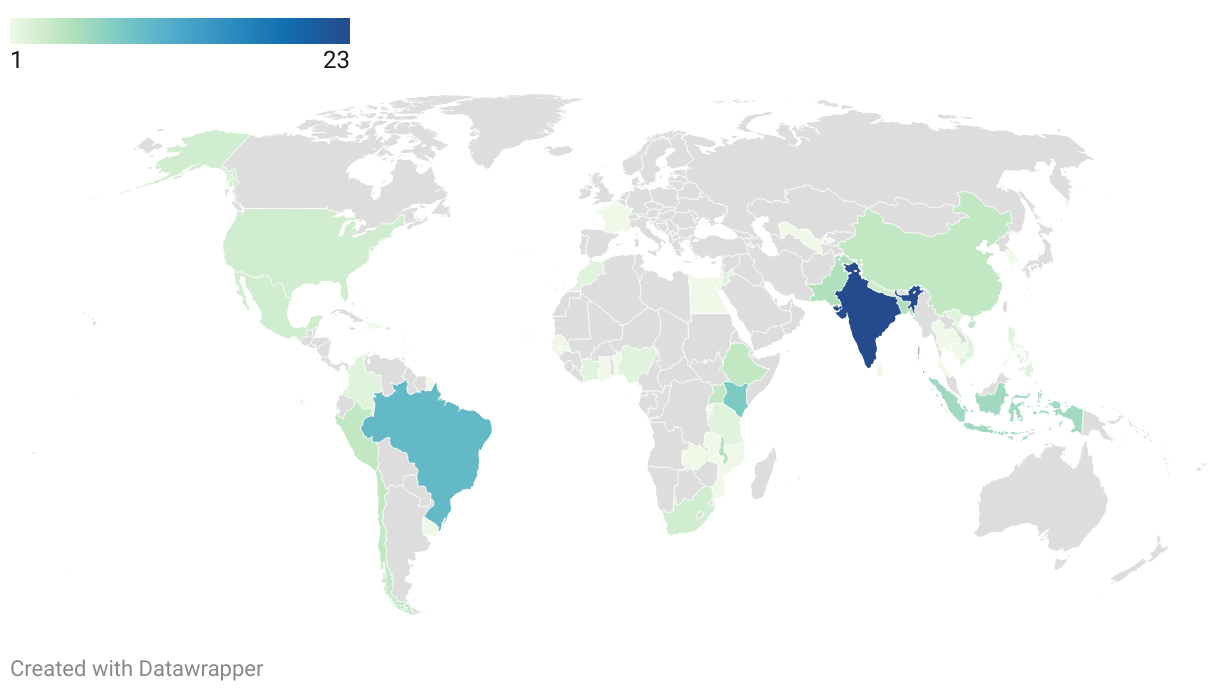

Finally, combating drug resistance is a global challenge and we welcome the president’s call to coordinate US efforts with WHO and other relevant organizations. China is believed to use four times more antibiotics on animals than the United States, but data in China are even harder to find than the US or Europe. As part of WHO’s Global Action Plan, we hope to see an international agreement on principles for responsible livestock production, beginning with the rigorous monitoring of antibiotic sales and use.

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.