Recommended

The UK is developing a new development strategy, with girls’ education and economic development likely to figure prominently. The government is also prioritising the Indo-Pacific region in its wider international strategy and will need to allocate its aid with partner countries there and in Africa. In this blog, we draw on a new analysis of the UK’s focus on lower income countries, and on Africa—where nearly two thirds of the world’s extreme poor live.

We find that the UK’s focus on the world’s poorest countries has been slipping over the last decade, The UK is giving aid to richer countries on average, and its poverty focus has fallen behind that of the US. Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) figures suggest that the UK is set to fall behind France, Germany, Japan and the US in its support to Africa in 2021/22, with UK Aid going to Africa less than half of what was spent just two years ago in absolute terms. For the first time since 2002, the percentage of bilateral aid spent in Africa will fall to under 50 percent of bilateral, regionally allocable aid.

The Integrated Review makes clear the UK will use a broad set of tools for influence in the Indo-Pacific and that the UK is “committed to the global fight against poverty”. To fulfill that pledge, aid should be focused where need and impact are greatest, and we conclude with three quantified standards for the new development strategy to quickly assess that commitment.

Strong poverty focus historically

As well as being one of few countries to meet the 0.7 percent of gross national income (GNI) aid target for any length of time, the UK also has a strong track record of focusing official development assistance (ODA) where it is most needed. In the accompanying note, we examine the average income of provider countries’ aid partners over time, weighted by the share of ODA each receives. This gives a more nuanced picture of poverty focus than looking at income groups alone, that mask significant disparities in income.

By this measure, the UK’s poverty focus is stronger than other major donors, particularly France and Germany. Whereas the weighted average income of UK’s aid partners in 2019 was around $5,600 (about equal to Ghana’s income), for France it was around $8,300, and for Germany it was $9,300 (more similar to Latin American economies such as Guatemala).

But two caveats cast shade on this positive finding. The first is that the share of the UK’s regionally allocable ODA has been shrinking for over a decade. This is largely because more and more aid is being spent domestically, for example through UK universities. In 2019, the UK spent 36 percent of ODA on projects with no identifiable recipient, far higher than other major donors.

The second is that the gap has narrowed over time. The weighted average income of UK’s aid partners has drifted up over the last decade, and in 2019 was 50 percent above its level in 2009. This is not just because global incomes have increased—the GNI increase in the median aid-eligible countries was tiny, at just 3.4 percent—and means that the typical recipient of UK aid no longer lives within the poorest quarter of the world’s countries.

Focus on Africa slipping

While economic performances have differed across different African countries, Sub-Saharan Africa remains home to 64 percent of those in extreme poverty - those who live on less than $1.90 a day. This is a percentage which is likely to increase over coming decades. It is also the region with the largest gap between financing needs and ability to raise domestic resources, suggesting that external finance (and ODA in particular) will remain vital. Given the relative success of other regions, a reasonable allocation would see an increasing share of ODA allocated to Africa.

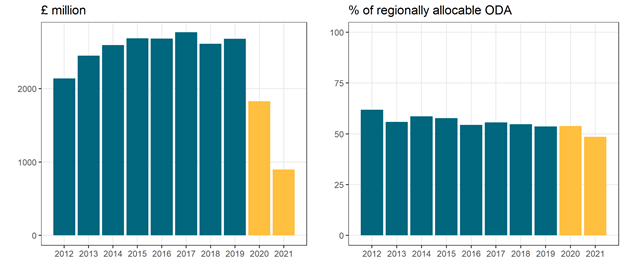

FCDO’s current plan is to do the opposite. For the first time in over 15 years, the percentage of regionally allocable ODA (which has an identifiable recipient) spent in Africa is budgeted to fall below 50 percent. Although the previous foreign secretary stated on April 27th 2020 that “fully 50 percent” of regionally allocable ODA would be spent in Africa in 2021/22, it will be the first year since 2002 in which that is not true.

When coupled with the overall decline in regionally allocable ODA, which has been reduced to make room for dubious accounting items, this will lead to a steep decline in the total amount of ODA going to the continent. FCDO is budgeted to spend £896 million in Africa (regional and country budgets). While some additional ODA will come from thematic spending, it is highly unlikely that this will be enough to prevent a more-than-50 percent decline in the budget relative to 2019. The FCDO’s total 2021/22 budget is similar to its level in 2012 (£8.1 billion, compared to £7.9 billion), but the budget for Africa is less than half.

Figure 1. FCDO aid to Africa (regional and country allocable)

Notes: DFID and FCO combined pre-2020. 2020 and 2021 denote financial years, and only includes aid directly allocated to African countries or regions, and so is not directly comparable to earlier years, as Africa may receive additional aid from thematic allocations.

Source: CRS and FCDO annual report 2021/22

This trend will see the FCDO become a minor player on the continent. After being second only to the US in total ODA spent in Africa (even before considering ODA from other departments) the FCDO is slipping behind Germany, France and Japan. Given a proportional increase in ODA to countries in Asia, this change in focus seems to be driven by the UK’s “Indo-Pacific tilt”. However, as colleagues will argue in a subsequent note, in most countries in the Indo-Pacific region any realistic ODA will be too small to gain the UK any real influence. This goal would be better served by non-ODA instruments, leaving a larger share of ODA for countries that rely on it more heavily. Somalia, for instance, receives ODA worth 38 percent of its GNI and is budgeted to take a 40 percent cut in ODA from the UK. South Sudan receives ODA worth 16 percent of GNI and the FCDO is cutting its budget in half.

Put regional focus top of agenda

The FCDO has set out priority areas for ODA spending, such as girls’ education or trade and economic development. These are worthy goals, but focusing thematically at the expense of location risks diminishing ODA’s potential impact. When you account for diminishing returns to wealth (the fewer pounds you have, the greater the impact of receiving each additional pound) aid spent in richer countries needs to be many multiples more effective than if they were spent in poorer countries.

Having squeezed the aid budget, the UK should be all the more focused on maximising the impact of the aid that remains. Maintaining a focus on the countries most in need is essential. GNI per capita might not be the only measure of need, but it is highly (negatively) correlated with need across a range of areas. If the government wants to improve girls’ education or trade and economic development, the biggest gains will probably be in the poorest countries.

In the coming development strategy, and based on this analysis, we propose three standards to quickly assess whether the Integrated review’s commitment to the global fight on poverty is fulfilled: i) Africa should receive at least half of the UK’s bilateral budget; ii) at least half of the total aid budget should be allocated to specific countries or regions; and iii) for the typical recipient country should be in the bottom quartile of global income.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.