Recommended

Blog Post

The Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) has been busy working toward a new regional approach to its economic growth mandate. In 2018, Congress granted MCC authority to pursue “concurrent” compacts with a single country, enabling the agency to undertake a separate, regionally focused compact alongside a typical bilateral agreement. This was an important advance for MCC. While the agency often invests in sectors with inherent regional implications like transportation infrastructure or energy, MCC was, until the passage of the new law, limited, in practice, to bilateral operations. Even when these bilateral compacts invested in activities relevant to regional integration (e.g., roads), it was nearly impossible for MCC to coordinate programming with any neighboring MCC-eligible countries since the timing of their respective compact development processes rarely overlapped.

MCC pushed hard for several years for concurrent compact authority to enable the pursuit of regional compacts. Now that the agency has it, Congress is almost certainly expecting the agency to deliver. Over the last two years, MCC has selected an initial set of countries and identified some potential high-impact, cross-border investments. But the process hasn’t been entirely smooth with the COVID pandemic slowing things down, as well as some hiccups around country participation.

It’s also become increasingly clear that while regional compacts represent an important new tool in MCC’s toolbox, they’re likely to remain a limited part of the agency’s overall portfolio, in large part because of MCC’s country eligibility requirements. This blog outlines the limitations and poses some questions the agency will need to address when considering its next regional investments.

MCC’s (potential) first regional investments

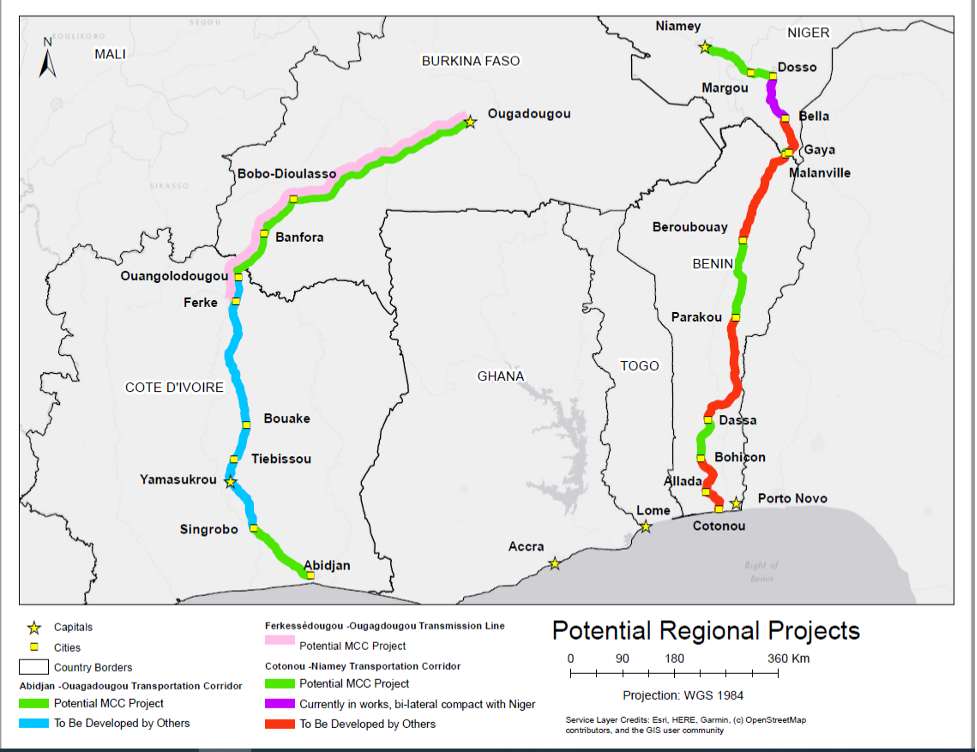

In late 2018, MCC selected Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, and Niger as the first set of countries to take part in one or more regional compacts. Within a year, the agency dropped Ghana from the list after the country failed to fulfill conditions under its existing bilateral compact. Working with the remaining West African countries and other partners in the region, MCC has identified two potential investments to support: (1) rehabilitating a transport corridor between the capital cities of Benin and Niger, and (2) building/upgrading a power transmission line between Côte d’Ivoire and Burkina Faso. MCC is also in the early phases of exploring a project to rehabilitate a transport corridor between Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso and Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, though this one is less well-developed at this point.

Potential regional compacts

Source: Millennium Challenge Corporation, as presented at an Oct. 20 CGD event; status of projects to be developed by other donors may have since changed.

Developing regional programs was never going to be easy. Negotiating with multiple partner countries is orders of magnitude more complex than bilateral conversations. And MCC faces the additional challenge of needing to adapt its standard, bilateral-oriented operational model to meet the needs of a new regional workstream. The agency has had to develop somewhat different approaches to identify cost-effective, growth-promoting projects, and is still working through what in-country implementation and coordination structures will look like.

MCC built some risk buffer into its pursuit of its first regional compact(s), starting by initially picking five potential partner countries. MCC understood that some groupings might not work out for a variety of reasons, whether that was an inability to find mutually agreeable, high-impact investments; insufficient cross border cooperation; or the need to pull back from a partnership due to policy declines. Selecting five countries gave MCC a higher chance that at least one or two viable projects would emerge. At this point, the agency is well on track.

The implications of MCC’s country selection system for the future of regional compacts

Selectivity about which countries MCC works with is a key feature of the agency’s model—one that’s helped fuel its long-standing bipartisan support and one that MCC has promised to uphold in its pursuit of regional programming. But this feature also presents significant challenges for realizing a regional model. First there’s the matter of identifying regions in which to invest. In practice, MCC can only work with the set of low- and lower-middle-income countries that meet a standard of performance on the agency’s country scorecards. Very few of these present possible pairings or groupings of contiguous eligible countries. The map below shows the countries that are currently developing or implementing a compact. Outside of West Africa, the only neighboring combinations are Mozambique-Malawi and Indonesia-Timor Leste.

But even sharing a border doesn’t get you all the way there. Eligibility for a regional agreement can be thwarted by setbacks in an existing compact partnership (as we saw with Ghana) or—hypothetically but definitely plausibly—by setbacks in policy performance. After all, MCC has put on hold, suspended, or cut the programs of around 40 percent of the countries it has ever selected, usually due to policy declines. In fact, there’s some risk of this coming to pass within the current set of regional compact candidates. MCC is undoubtedly keeping its eye on Benin, where, over the last couple of years, the government has made moves to restrict political pluralism and participation and curb media freedom. The stakes of responding to policy declines are higher with regional compacts, however. Any decision by MCC to curb its engagement with one country will have potential knock-on effects for the other countries involved in the regional program.

Key questions MCC will face about selecting countries for regional compacts

What would happen to the other party/parties in a regional compact if one country is dropped? MCC doesn’t face an immediate need to answer this question, but uncertainty about the trajectory of policy performance in Benin should prompt thinking about what, hypothetically, would happen to the rest of a regional compact being developed or implemented if MCC must cut ties with one of the countries. Can the agency proceed with the other country’s portion of the compact? The law says only that a country can have a concurrent compact “for purposes of regional economic integration, increased regional trade, or cross-border collaborations.” Investing in one country’s contributions to a regional project (e.g., rehabilitating a portion of road up to a national border) could still plausibly count as fostering regional integration. But would that approach be consistent with expectations for the agency?

Does a regional compact have to tie into another MCC project? In a similar vein, does a regional compact in a country have to link directly to another MCC-funded project across a border? That is, does the regional neighbor have to be MCC eligible? The subset of MCC-eligible countries in a given geographic area may not always make the most sense for a regional investment. Looking just at West Africa, for instance, it’s noteworthy that Nigeria—which is the region’s economic powerhouse but doesn’t pass MCC’s scorecard—can’t be a direct part of MCC’s regional approach. But would an MCC-funded project in an MCC-eligible country that links to an externally funded project in a country like Nigeria yield higher returns than a project that links to another MCC project in a much smaller economy? This seems like a question worth asking and an option that should be on the table. Not being bound to the (very small) universe of contiguous eligible countries would broaden the scope of how MCC could support regional integration and potentially open up higher return opportunities. Of course, regional integration projects that tie into a non-MCC funded project could presumably be done as part of a standard bilateral compact. But concurrent compact authority could allow MCC to take advantage of regional investment opportunities that arise after the bilateral compact is underway.

Does regional have to mean cross border? Looking at the future of regional compacts more broadly, there’s the question of whether countries involved in a regional compact would need to share a border, or whether MCC can conceptualize “region” more broadly. Certainly, the kinds of things MCC often invests in—transportation infrastructure, energy—require physical proximity, but could there be investments in sectors like education/vocational training or trade policy that could be relevant for countries within a region, even if they’re not contiguous? This would also expand the potential pairings/groupings of countries, at least within West Africa—or even the African continent more broadly—where there are several MCC countries.

We’ll continue to watch the development of MCC’s first regional compacts with interest. Looking forward, how far MCC goes with regional compacts will depend in large part on finding regions in which to invest. The agency’s country selection criteria will limit possibilities. But even within these constrained options, there may remain room for creativity in defining what makes a regional project.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Center for Global Development