Recommended

On December 11, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) will hold its end of the year board meeting to select which countries will be eligible for MCC’s FY2019 funds. As we do every year, CGD’s US Development Policy team has been monitoring how countries perform on MCC’s scorecards, and examining the political climates and—where relevant—previous MCC program performance for countries likely to be up for debate. In addition, we’re thinking through how MCC’s new authority to pursue regionally-focused investments could impact partner selection this year. Here are the key questions on our minds about this year’s selection process and our predictions for which countries will be chosen next week.

This Year’s Key Questions

1. MCC can now pursue regional compacts—how will the board think about eligibility?

This past spring, with passage of the AGOA and Millennium Challenge Modernization Act (H.R. 3445), Congress gave MCC the authority needed to pursue regionally-focused programming. The change allows MCC to have up to two concurrent compacts with a single country, permitting the agency to pursue both a standard, bilateral compact with a country as well as a separate regionally focused investment coordinated with similar programming in neighboring countries. This marks an important evolution for MCC, which is now better placed to address critical—and potentially high return—cross-border constraints to growth.

Regional programs will be more complex and riskier than MCC’s standard bilateral programs. And there are a number of questions the agency will need to answer as it seeks to use its new authority. The first questions the agency will need to tackle involve selection.

MCC has issued assurances that all countries involved in a regional investment will need to pass the scorecard and maintain good policy performance. While the legislation doesn’t specify that the regional projects that concurrent compacts fund must link only to other MCC-eligible countries, MCC is likely looking, at least at first, to create links among its current partners. The decision to pursue a regional program, however, will need to rely on more than the geographic proximity of one or more scorecard-passing countries. MCC will need to have a sense of where regional opportunities exist and a good grasp on whether neighboring countries are likely to work together well to address them. With bilateral compacts, programming decisions are made only after a country is made eligible. The selection process for regionally focused compacts will require greater upfront prospecting to explore possible programming to identify where high-impact, mutually agreeable investments might exist. But there’s only so much that can be done at this stage. MCC can’t spend money, conduct analyses, or start working with countries to identify priorities before countries are eligible. So the board must determine the best regional bets based on the information it has available.

The board may address the uncertainty about viable regional investments by selecting several contiguous countries. This would allow MCC to pursue more in-depth prospecting and analysis to determine which pairings or groupings among those selected represent the most feasible regional opportunities (i.e., high return projects, mutual interest and commitment by all prospective parties). This increases the chance that it will end up with at least one or two good investments.

It also means that not all countries selected for a concurrent compact may end up as part of a regional investment. The idea that not all eligible countries would proceed to a compact isn’t really new for MCC. The agency’s original vision was that once countries were picked, they would then compete among themselves for who could submit the best investment proposals. In practice, however, political pressure and/or pressure to expend funds has led MCC to sign a compact with essentially every eligible country whose relationship hasn’t been curtailed due to deteriorating policy performance or issues with the bilateral relationship. Of course, the search for viable regional investments won’t be a process of inter-country “competition” as much as it will be one of identifying where the best opportunities lie. But if the board does indeed decide to select more countries for potential regional investments than it thinks MCC might fund, it should be aware of past dynamics around pressure to fund the countries it picks. That’s a bit of a risk. But the approach of selecting multiple prospective regional partners—knowing up front that not all may ultimately become part of a program—may be the best approach to identify good projects between or among groups of countries that are willing and able to collaborate.

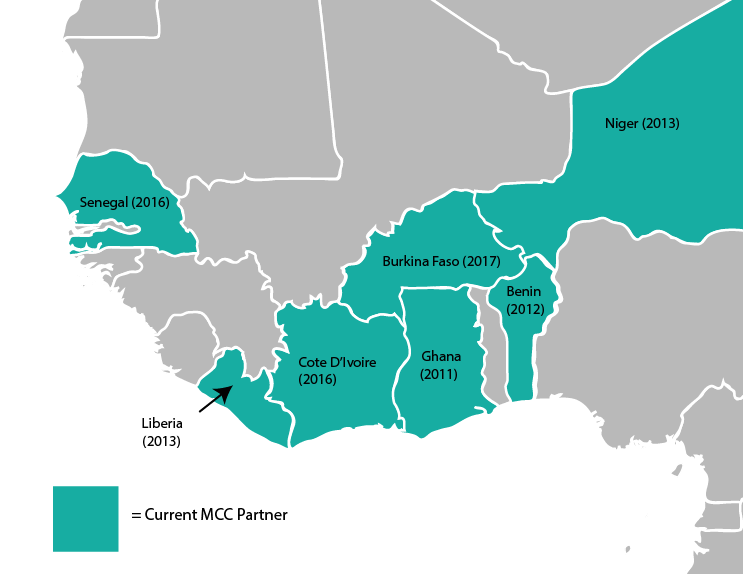

In terms of where a regional investment might take place, MCC is almost certainly eyeing West Africa, where the agency has a number of current partnerships with contiguous countries.

West African countries with current MCC compacts with the year compact development began

Source: Author’s visualization

2. Will MCC select a country for a third compact for the first time?

For the first year, MCC is faced with a serious decision about whether to select a country to develop a third compact. MCC has selected several countries for second compacts over the last several years, but with some second compacts closing out, or getting close, the prospect of third compacts has become a live issue.

MCC’s authorizing legislation permits the agency to enter into one or more follow-on compacts with a country. However, some stakeholders have had reservations, believing the need for continued MCC investment suggests failure of previous investments and/or that a longer-term partnership erodes one of MCC’s distinctive features—the five-year time clock. As we’ve written previously, these arguments are misguided, and entering subsequent compacts makes very good sense for MCC.

While there was some ambitious rhetoric associated with MCC’s creation, compact success does not mean “transforming” a country; in fact, “transformation” is an unrealistic definition of what success for any aid program might achieve. A successful MCC program is one that helps a country address some important constraints to sustained increased economic activity. Additional compacts can build upon these or tackle others. Subsequent compacts also don’t mean indefinite support. All compacts have a fixed five-year timeframe, which forces a clear exit point, and creates a juncture at which MCC must assess whether to pursue another partnership. In other words, subsequent compacts are in no way automatic. Partnerships that do extend beyond a single compact can capitalize on institutionalized relationships and strengthen MCC’s aid effectiveness practices—rigorous approaches to country ownership, good governance, transparency, cost-effectiveness, and results—as part of that relationship. And finally, the fact remains that if MCC is to stick to its mandate of working only with relatively well-governed, poor countries, the best future partners will be among the set of countries with which it is already working. MCC is currently partnering in some form with nearly two-thirds of the countries that meet its scorecard criteria (most of the rest are tiny islands or have governance issues that raise significant concern—even when passing the scorecard). And, as the graph below shows, very few new countries meet these criteria in any given year. Simply put, if MCC’s current partners maintain good governance and demonstrate commitment to successful implementation of their prior compact, it makes little sense to disqualify them from further support solely on the basis of having concluded a compact in the past.

Number of Countries Passing MCC's Eligibility Indicator Criteria for the First Time

Source: Author’s visualization

That said, MCC should enter the world of third compacts cautiously. Congressional and other stakeholders have sought assurances that the bar for second compacts be higher. And indeed it is—only 12 of the 29 countries that had a first compact have gone on to become eligible for second compacts. Third compacts will undoubtedly be expected to be exceptional, too. So the live question for this year’s meeting will be whether there are any countries that make the grade. Only two countries are in the running, given the timing of their second compacts—Cabo Verde, whose second compact concluded at the end of last year, and Georgia, whose second compact will end in July. Given the scrutiny any third compact choices will likely receive, tiny Cabo Verde is an unlikely candidate to be at the vanguard of a potential new cohort. Georgia could be a possibility; we discuss the related issues and offer a prediction below (spoiler: we’re guessing it won’t be picked this year).

Another route to a third compact could be through regional programming if a country picked for a regionally-focused concurrent compact is implementing a second compact. While this would be a somewhat different scenario than having a third compact of the “traditional,” purely-bilateral sort, it could nonetheless mark an initial inroad into third compact territory. And it’s a possibility this year.

3. What’s the budget outlook and how will it constrain choices?

One of the odd features of MCC’s selection process is that since the appropriations process is rarely complete by the time of the December board meeting, the pot of money that countries are selected to draw upon is often unknown at the time they are selected. This puts a bit of guesswork into the board’s calculations. The president’s FY2019 budget request for MCC is $800 million, around 12 percent lower than last year. Congress ignored the president’s lowball request from last year, but it’s hard to say how the numbers will ultimately play out. There is a question of whether—and to what extent—MCC’s new concurrent compact authority could require additional resources.

MCC cannot afford to select all the countries that pass the scorecard (nor would they all be top choices for reasons of size and policy performance). As always, the board will have to prioritize. On average, the board picks three new compact partners a year, but this may be a bigger year. First of all, MCC is no longer pursuing a compact with the Philippines, so a chunk of money from previous years can be reallocated to other countries developing compacts; this frees up more of this year’s money for new selections. In addition, the possibility of concurrent compacts will likely boost the number of eligible countries over and above the set of bilateral choices.

4. How will this administration’s foreign policy priorities influence choices?

MCC’s largely transparent, evidence-based selection process was intended to depoliticize eligibility decisions. And the record of past selections shows that policy performance is indeed the main criterion for eligibility. But while US geopolitical interests haven’t trumped MCC’s focus on good governance, they almost certainly factor to some degree into compact eligibility decisions.

For example, the Trump administration has expressed interest in expanding US engagement in the Indo-Pacific region, noting US interests in growing economic ties and responding to the rise of China. MCC’s board will likely weigh those broader US government priorities when evaluating plausible contenders for eligibility in the region. None are completely straightforward choices. Sri Lanka is up for reselection to continue compact development, but its political environment has recently turned tumultuous. Indonesia, in the running for a second compact, is huge and aid is a less significant flow. And, as always, there are several tiny Pacific Islands that pass or come close to passing the scorecard. MCC has always passed over these for eligibility, despite their good scorecard performance, due (presumably) to limited opportunity to affect growth in a tiny economy. We’re guessing that rationale will continue to prevail, though the administration’s interest in the Pacific may shift the conversation somewhat.

A Brief Overview of How MCC’s Selection Process Works

For more detail, see MCC’s official document or our short synopsis (see section “How the Selection Process Works,” p. 2-4).

-

MCC’s country scorecards provide a snapshot of a country’s policy performance compared to other low- and lower-middle-income countries. To “pass” the scorecard, a country must meet the performance standards on 10 of the 20 indicators, including the Control of Corruption indicator and one of the democracy indicators (Political Rights or Civil Liberties).

-

The scorecard is only the starting point. The board also considers supplemental information about the policy environment, as well as whether MCC could work effectively in a country, and how much money the agency has.

-

Once a country is selected as eligible for a compact, it must typically be reselected each year until the compact is approved (usually 2-3 years).

-

A country implementing a compact can be considered for a subsequent compact if it is within 18 months of completing its current program. When evaluating countries for subsequent compacts, MCC looks for improved scorecard performance (especially on the governance indicators) and considers the quality of the previous partnership.

Countries that Pass MCC’s FY2019 Scorecard Criteria

| Lower Income Countries | Lower Middle Income Countries |

|---|---|

| Benin | Bhutan |

| Burkina Faso | Cabo Verde |

| Comoros | Georgia |

| Côte d’Ivoire | Indonesia |

| Gambia | Kiribati |

| Ghana | Kosovo |

| India | Micronesia, Fed. Sts. |

| Lesotho | Mongolia |

| Malawi | Philippines |

| Nepal | Sri Lanka |

| Niger | Tunisia |

| Pakistan | Vanuatu |

| Sao Tome and Principe | |

| Senegal | |

| Tanzania | |

| Timor-Leste | |

| Togo | |

| Zambia |

MCC Eligibility Predictions for FY2019

Below are our predictions for FY2019 MCC eligibility. We don’t cover all 70 candidate countries since over half of them have low enough scorecard performance to make them unlikely picks. Instead we restrict our analysis to countries that:

-

pass the scorecard criteria, except those not in the running for any kind of eligibility decision, because they are currently implementing compacts (while being outside of the timeframe for subsequent compact eligibility) and are unlikely prospects for a concurrent regional compact.

-

are up for reselection to continue compact development.

-

don’t pass the scorecard but come close enough to be considered for threshold eligibility.

Click on any country name below to read a brief analysis and rationale for our prediction.

First compact eligibility, new selection

Kosovo (possibly)

MCC’s relationship with Kosovo has been a bit complicated. When Kosovo first passed the scorecard, in FY2016, MCC’s board selected Kosovo for compact eligibility. The next year it failed again, and the board downgraded it to a threshold program. Since then, however, Kosovo has passed the scorecard, giving it a 75 percent passing record over the last four years. Kosovo is currently implementing the second largest threshold program in MCC history ($49 million), but MCC has selected countries for compacts in the midst of threshold program implementation before.

Still, it’s not an entirely obvious choice. Kosovo’s per capita income is just $5 under the ceiling that determines whether a country can be candidate for MCC funds, raising the risk that it might not be among the pool of MCC countries in future years. Proximity to the income threshold can complicate things, not least from an optics perspective, but it’s not an insurmountable hurdle since Kosovo could still use funds from the year(s) it was eligible. (Relatedly, the rigid ceiling on MCC candidacy is pretty insensible.) And it’s helpful that Kosovo may be able to move relatively quickly toward compact signing, having already completed the required constraints to growth analysis as part of its threshold program development. But income-related “graduation” is not the only risk. While Kosovo has developed a solid scorecard passing record, its Control of Corruption score is subject to more volatility than many countries. There isn’t much underlying data that feeds into it—few sources cover Kosovo—so small changes can be amplified, causing bigger swings in scores, even in the absence of actual changes in governance quality.

On the other hand, Kosovo is also one of the poorest countries in Europe, a region where MCC has historically had limited presence. It’s also a good friend of the United States, which has supported the small nation since the 1990s and was among the first to recognize Kosovo’s independence in 2008. And Kosovo has long been interested in an MCC partnership. There probably aren’t many years left for MCC to select Kosovo before its income becomes too high. This may be the year.

Second compact eligibility, new selection

Indonesia (possibly)

Indonesia has been an MCC partner since signing a threshold program in 2006. Its first compact closed in early 2018, putting it squarely in the running for a second compact. As far as scorecard performance goes, Indonesia’s story is a good one. In FY2010, Indonesia moved from the low-income country pool to the more competitive lower-middle income country pool and failed the scorecard…for years. It passed for the first time last year, and passes again this year, with a solid-looking upward trajectory on the Control of Corruption indicator (which had given it trouble in the past). MCC looks for “improved scorecard policy performance” for second compact eligibility, and Indonesia fits that bill nicely.

That said, Indonesia isn’t a slam dunk. Some might point to its first compact performance, noting it wasn’t able to complete the programmed activities, leading to a deobligation of $52 million. But Indonesia’s first compact suffered from questionable decisions and poor design, and there’s no reason to believe these factors would similarly plague a future compact—especially since it is likely to focus on different areas. The bigger issue is the question about the potential impact another major MCC investment could have. It’s the fourth most populous country in the world with an economy that receives trillions of dollars of foreign direct investment each year, making aid—even a large grant from MCC—small potatoes.

That said, Indonesia is a strategic partner of the United States, and the Trump administration has expressed a particular desire to expand US engagement in the Indo-Pacific and boost the United States’ economic presence in the region to counter China. With few other current prospects for eligibility in the region, Indonesia may be an attractive option this year.

Malawi (probably)

Malawi wasn’t selected last year—the first year it was up for second compact consideration—but at that time the government had nearly a year left of its first compact and MCC may have preferred to keep the focus on successful implementation. Now that the compact—which focused on improving the country’s power sector—is completed, it will likely be considered differently.

Malawi—one of the lowest income countries in the entire candidate pool—maintains exceptional scorecard performance. It’s passed the criteria for 12 years in a row—a record matched by only four other countries. And it passes 18 of the 20 indicators this year. How MCC interprets its somewhat vague second compact criteria of “improved scorecard policy performance” will matter, however. While the important governance indicators don’t demonstrate a clear upward trajectory, they’ve been steadily high. MCC did briefly suspend Malawi in 2012 due to democratic backsliding, but the country quickly reversed course, leading MCC to reinstate the program after a few months. And Malawi does pass a couple of additional indicators than it did when it started its first compact. Considering how rare consistently good scorecard performance is, it would be entirely justifiable for MCC to assert that Malawi meets the higher second compact bar. One wild card is the country’s presidential election coming in May next year. The board will likely choose Malawi for a second compact anyway, and proceed slowly with compact development until the new administration comes on board.

Concurrent compact eligibility for regional program, new selection

Benin (possibly)

Benin is a consistent scorecard performer, having passed eight of the last nine years. It’s also been a long-time partner of MCC. It’s currently implementing its second compact, focused on the power sector. Benin’s solid scorecard record, its proximity to other MCC compact countries, and its work on power—a sector MCC has mentioned as good bet for its regional investments—make it an attractive choice.

Burkina Faso (possibly)

Burkina Faso is currently developing a second compact, but due to its central location among MCC compact countries in West Africa (it shares borders with all of the countries listed in this section), it may be a contender for a concurrent compact that would have a regional orientation. In theory, because Burkina Faso’s standard compact is still under development, any regional-focused activities could presumably be built into that package. But if the country is to be part of a regional program, it would probably make more sense to select it for a concurrent compact specific to the regional investment so as not to hold up progress on the original compact.

Côte d’Ivoire (possibly)

Côte d’Ivoire is a major West African economic hub with the third biggest economy in the region. If MCC is eyeing West Africa for its first regional investments, Côte d’Ivoire is almost certainly on the agency’s mind. It’s also become a consistent performer on the scorecard, having passed the last five consecutive years. MCC is likely to weigh the consistency of good governance heavily for regional investments. When an investment requires the participation of multiple countries, backsliding in any one of them—to the point that MCC might have to curtail engagement—creates more far-reaching consequences. Côte d’Ivoire signed a compact in late 2017 focused on transport and secondary education. The board may select it to begin developing a concurrent compact linked to a related investment in a neighboring country—perhaps Ghana or Burkina Faso.

Ghana (possibly)

Ghana is another major locus of economic activity in the region, with the second largest economy in West Africa. The country has also passed the scorecard every single year but one, a record matched or surpassed by only two countries. For regional investments, MCC will almost certainly want to prioritize countries with relatively reliable records of good governance since backsliding by any party to a regional investment—to the point that MCC might need to cut them off—would create problems for all involved. Ghana is also geographically well-situated. Two of its neighbors—Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire—have strong scorecard performance and are either currently developing a compact (the former) or are under consideration for a concurrent compact (the latter). Ghana is currently implementing its second MCC compact (focused on power and scheduled to conclude in 2021), so a concurrent compact would quietly make Ghana the first recipient of a third compact. For that, it seems a solid choice.

Niger (possibly)

Niger is currently implementing its first MCC compact, a program focused on water and agriculture. And despite being among the most fragile of MCC’s compact countries (by these measures at least), it has passed the scorecard for the last eight years in a row. It doesn’t share a border with the two big economies, Côte d’Ivoire or Ghana, but it’s connected to both Benin and Burkina Faso and may have potential as part of a regional investment.

First/second compact eligibility, reselection to continue compact development

Burkina Faso (probably)

First selected for a second compact in 2016, Burkina Faso passes the scorecard for the eighth year in a row, and is likely to be re-selected to continue developing its compact. MCC recently performed a constraints to growth analysis in the country, which highlighted two specific constraints: cost, access, and quality of energy, and a less skilled workforce. The MCC and Burkina Faso teams are now developing additional analyzes and concept notes for work in both sectors.

Lesotho (probably)

Originally chosen for a compact in 2013, MCC reselected Lesotho last year after a two-year deferral from the board, due to concerns about political instability and challenges in the military and security sector. After marked improvements, MCC moved forward in allowing Lesotho to develop a compact, and it’s a safe bet for reselection again this year. The government and MCC are currently working on a constraints analysis that is expected at the end of 2018.

Senegal (probably)

Senegal was selected for a second compact in FY2016, and continues to perform well on the scorecard. MCC recently submitted the proposal for a compact worth $550 million that will focus on strengthening the energy and electricity sectors. The agency has signaled the compact will be presented to the board this year.

Timor Leste (probably)

MCC selected Timor Leste to develop a compact last year, and the country passes the scorecard once again. A recently completed constraints analysis identified unsustainable fiscal expenditures, an uncompetitive exchange rate, weak economic policies and institutions, and low human capital as the country’s primary challenges. The compact is expected to focus on one or more of those areas.

Tunisia (probably)

Tunisia passes the scorecard for a third year in a row. After conducting a constraints analysis, the Tunisian government is preparing concept notes on the three identified constraints: excessive market controls of goods and services, excessive labor market regulations, and water scarcity. Per MCC, the compact is estimated to cost $292 million, and MCC anticipates it will be presented to the board in June 2019.

Threshold program, new selection

Ethiopia (possibly)

Ethiopia has never passed the scorecard, falling well short on the critical democracy indicators, as well as many others, so it may seem to be a surprising choice for this list. But with the unprecedented transition underway (that’s not yet reflected in the indicators), it’s not as far-fetched as it might seem. In the span of the last six months, the new prime minister has released thousands of political prisoners, lifted bans on opposition parties and the media, cracked down on corruption, made peace with rival Eritrea, privatized state-owned enterprises, appointed a cabinet of 50 percent women, and more. With a limited pool of new partner countries emerging, MCC may be interested in supporting this transition and beginning to develop a partnership with a new country—one that happens to be a major US ally, strategic partner, and aid recipient. A threshold program would allow MCC to actively engage on a limited basis while monitoring whether a deeper engagement may make sense in the future.

Threshold program, reselection

The Gambia (probably)

After the country’s democratic transition in 2017, the Gambia quickly emerged as a contender for a threshold program. MCC selected it last year and has been developing a threshold program. It is likely to be reselected this year. Though the Gambia passes the scorecard for the second year in a row, MCC will probably continue with a threshold program rather than moving quickly to a compact as the country’s transition to consolidated democracy further advances.

Countries that pass the scorecard but are unlikely to be selected

Federated States of Micronesia, Comoros, Kiribati, Sao Tome de Principe, Bhutan, Vanuatu

All have passed the scorecard in several prior years but have been passed over for eligibility, presumably because of their small size (all have populations under a million). Though MCC does not have an official minimum size requirement for compact eligibility, the board has demonstrated a preference against the selection of small countries.

Cabo Verde

Cabo Verde is also small (population 540,000), but, unlike the small countries listed above, it has had a long partnership with MCC, completing its second of two compacts in November last year. If the board were to select Cabo Verde again it would be for a third compact, but because third compacts will be expected to be rare and special, it would be risky for MCC to pick tiny Cabo Verde as the vanguard of a potential new cohort of third compact partners.

Georgia

Georgia is a plausible contender to be the first country selected for a third compact. It regularly passes the scorecard and has been a solid partner through the first two compacts. It’s also an important strategic ally. We’re guessing the board won’t pick it this year, however. When the board meets, Georgia will have eight months left of its second compact, and in recent years the board has preferred to hold off on decisions about subsequent compacts until the current programs are closed or almost closed. Georgia is also just below the income ceiling for MCC candidacy, raising the risk that it might “graduate” out of MCC candidacy soon. Though MCC can continue to work with countries that exceed the income threshold, as long as they use funds from the fiscal year(s) in which they were eligible, doing so has, in the past, required some extra explanation…and convincing of reticent congressional stakeholders.

India

India regularly passes the scorecard, but neither it nor MCC—not to mention many members of Congress—think a compact is an appropriate tool for the bilateral partnership. India is, after all, the world’s seventh-largest economy and a foreign aid provider, not to mention its over $300 billion in foreign exchange reserves. MCC and India have, however, discussed how they might collaborate on MCC’s programming in South Asia, including in Nepal and Sri Lanka.

Philippines

After a long history with MCC, last year the Philippines notified the agency that it was not interested in continuing to pursue a second compact, after years of negotiations and development. The government of the Philippines’ announcement came after MCC deferred selecting the Philippines for FY2017 due to “concerns around rule of law and civil liberties” (in particular, concerns about the president’s support for the extrajudicial killings of thousands of people suspected of involvement in illicit drug activity) and was poised to reassess the situation again in FY2018. Nothing has fundamentally changed since last year’s decision that MCC and Philippines part ways, making it an unlikely choice this time around.

Sri Lanka (up for reselection to continue compact development, but a deferral is likely)

Sri Lanka was among the first set of countries MCC ever selected, but the relationship came to a halt in late 2007 due to the country’s civil war. The relationship restarted in FY2016 when MCC selected it for a threshold program and deepened the following year when the board made Sri Lanka eligible for a compact. Because Sri Lanka conducted a constraints analysis as part of developing a threshold program, the compact proposal has advanced quickly and is already in late stages of development. The program is expected to focus on transportation and commercial land use and is estimated to cost $450 million.

However, recent political turmoil will make Sri Lanka a topic of serious conversation at the board meeting. In a constitutionally questionable move, Sri Lanka’s president removed his prime minister and replaced him with the former president, who is popular for bringing about the end of the country’s civil war, but whose tenure was marred by accusations of human rights abuses. Loyalists of the former president/now prime minister have undermined opposition to his return to power by pushing for parliament to be dissolved to prevent a no confidence vote on the matter, and to delegitimize the body when it did convene and vote against him. As the situation escalated, tens of thousands of people have been protesting in the capital. The political situation is quickly evolving, and there may be some definitive resolution before the board meets on the 11th that would point to a firm call for MCC to make. But it’s more likely that MCC will defer a decision on whether to reselect Sri Lanka (as it did in response to political turmoil in Lesotho) until more clarity on the trajectory of events emerges.

Tanzania

MCC suspended its partnership with Tanzania in 2016 due to the flawed and unrepresentative conduct of a 2015 election in Zanzibar, as well as moves by the government to stifle dissent and control information. There has been no marked improvement in any of these areas in the past year.

Togo

Togo passes the scorecard for a third year in a row. Nevertheless, last year, MCC flagged concerns with the political rights and civil liberties environment. Though the situation improved enough for MCC to proceed with approving a threshold program with Togo earlier this year, the agency noted it would “continue to closely monitor citizens’ rights to freedom of expression and association, and due process in light of recent events.” MCC is likely interested in sticking to threshold program implementation while it monitors events. Furthermore, while Togo passes the democracy hurdle on the scorecard, the current president has run the country since 2005, and his father for decades before him. MCC will need to weigh whether having one family in charge of the country for 50 years complies with the spirit of its eligibility criteria before deciding to select Togo for compact eligibility. It’s unlikely to be a choice the board makes this year.

Zambia

Zambia’s first compact concluded in November 2018, so it could be in the running for a second compact this year. It seems unlikely to be selected. Though it passes the scorecard for the eleventh straight year, it shows slight downward trends on several key governance indicators, rather than the “improved scorecard policy performance” MCC looks for when deciding about second compact eligibility. The scorecard scores seem to reflect the political environment. In mid-2017, Zambia’s president declared a state of emergency, shut down the country’s most independent newspaper, and intimidated opposition figures. In addition, several European donors recently announced they were withholding funds due to concerns about corruption and mismanagement, and the IMF suspended its program with Zambia early this year due to excessive borrowing and macroeconomic instability. These concerns, plus competition from several other relatively strong prospects for compact eligibility this year, suggest the board will likely give Zambia a pass this year.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.