Recommended

Press Release

In a recent CGD working paper, I showed how a simple indicator constructed from a small set of economic and institutional variables was able to identify in 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent global shocks, those emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) that would be most economically and financially affected if an external shock were to materialize. The countries that this indicator identified as the least resilient in 2019 had either defaulted or were close to default by 2022.

How stable do emerging markets look now, in 2023? Which countries would be most and least resilient if another global adverse shock were to happen? After all, in its recent assessment of the world economy during the annual meetings last month, the IMF raised the alert about important headwinds for EMDEs, including the persistence of high interest rates that will keep the international cost of financing high for a long time. Most importantly, there are also large uncertainties and risks—including on oil prices—resulting from geopolitical developments, not least the recent turmoil in the Middle East, which analysts show has potentially large global recessionary effects.

Luckily, a good part of the data used to calculate the Resilience Indicator comes from the IMF World Economic Outlook, which has just been updated. Together with recent data from the World Bank and some other national sources, we are in a position to update the Indicator for the emerging markets group. In December, as more data becomes available, we will also be able to update the Indicator for developing countries.

How do countries look in 2023 when compared to 2019?

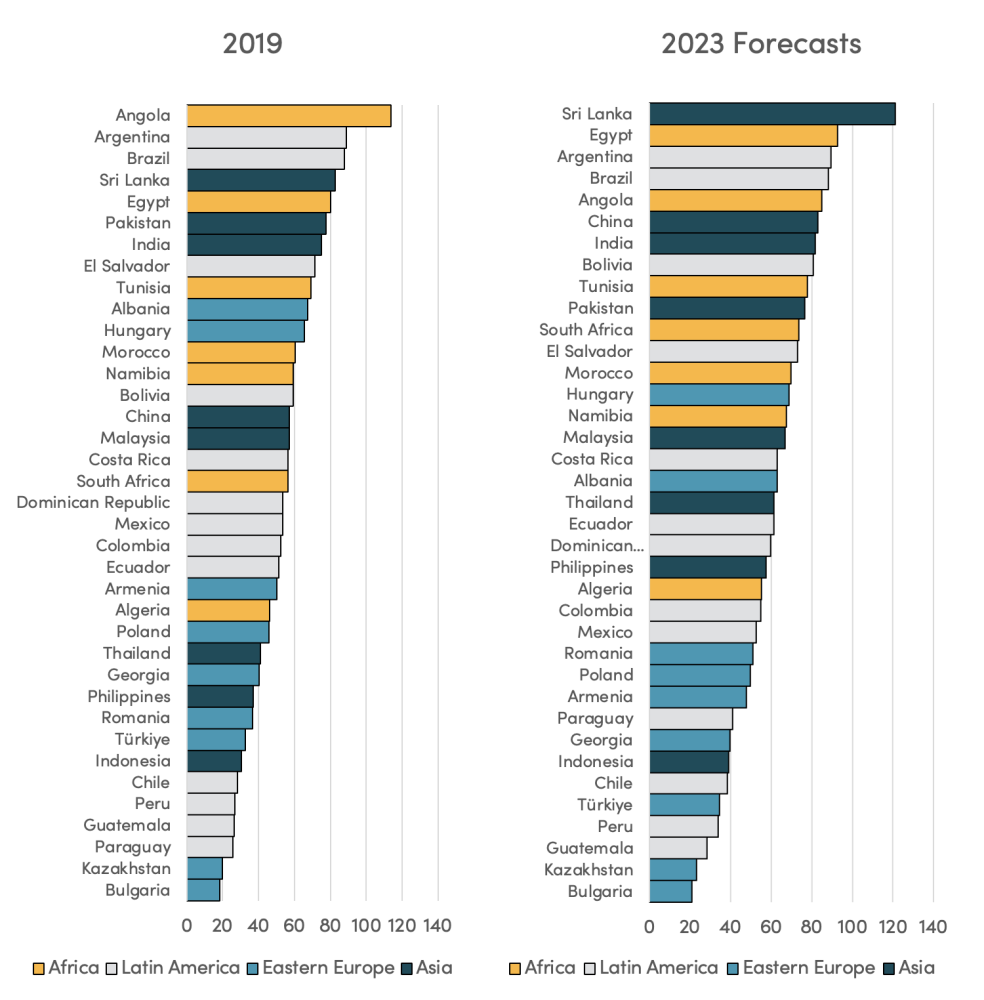

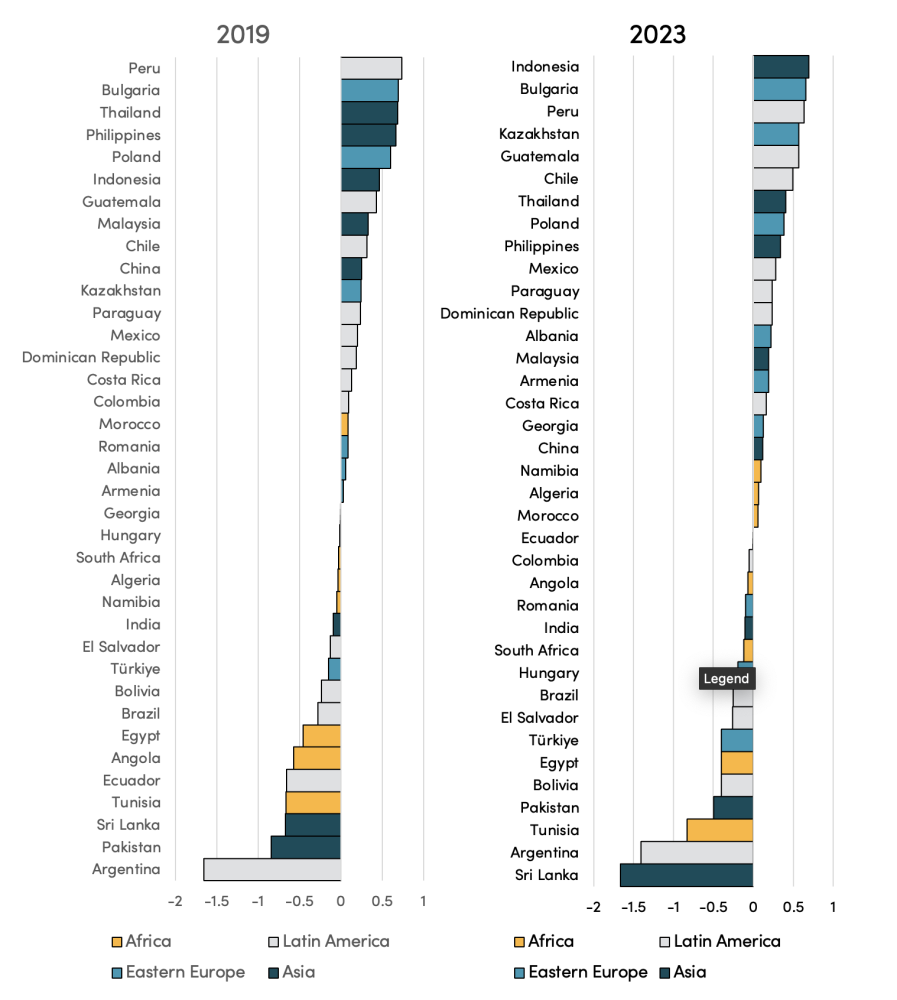

Let’s start by looking at some of the components of the Indicator.[1] Across a sample of 37 countries, emerging markets are now more vulnerable than in 2019 on an overall basis. The scars of the 2020-2022 shocks that started with the COVID pandemic and the subsequent multiple shocks, such as Russia’s war on Ukraine and the US Fed’s increases in interest rates, are deep and have weakened emerging markets’ economic and financial conditions.

Here are the facts:

-

In 2019, only 4 countries (Tunisia, Pakistan, Argentina, and Sri Lanka) had ratios of external financing needs (as measured by short term external debt plus current account deficits as a proportion of international reserves) above 100 percent. Now, 12 of the 37 countries we examined, or about one third, are in that position.

-

Close to 60 percent of the countries ranked by the Indicator have fiscal deficits above 4 percent in 2023, almost double the number that did in 2019.

-

The proportion of countries passing the (allegedly dangerous) threshold of a 60 percent public-debt-to-GDP ratio sharply increased from 30 percent in 2019 to 54 percent in 2023—consistent with larger fiscal deficits.

Figure 1. General government debt in emerging markets (as percentage of GDP)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook and Staff Reports

-

In line with the global inflation problem that began in 2021, only 6 countries now have inflation rates within the range of their central banks’ announced targets: Brazil, Bolivia, Dominican Republic, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Paraguay. In 2019, 20 countries, or more than half of the countries in the Indicator, had inflation rates within targets.

So, what countries are the least resilient today?

The Resilience Indicator, whose methodology can be found here, ranks countries according to their economic strength to withstand and deal with adverse external shocks. Higher values of the Indicator denote greater resilience. Computing the indicator for 2019 and 2023 yields the following results:

Figure 2. Resilience Indicator 2019 vs. 2023

First a clarification: the values of the indicator are not comparable across time, not least because the interval is open-ended; namely there are no defined limits to the value of the indicator. At each point in time, what the indicator tells is the macroeconomic strength of a country relative to its peers. Why does it matter? Because evidence shows that investors strongly differentiate between emerging markets, and that these differentiations are based on the behavior of fundamentals. Countries with the weakest fundamentals at the time an adverse shock hits would suffer the most. In other words, initial conditions matter, and they matter a lot! A complete assessment of resilience across countries requires analyzing the overall Indicator as well as its components.

These are some key results:

-

The most vulnerable countries in 2019 continue to be so in 2023. Argentina, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Tunisia have very large and unsustainable large public debt ratios. Sri Lanka is quite notable since unsuccessful negotiations to secure debt relief from China, its largest bilateral lender, are delaying the country’s much-needed access to IMF funding. In both Argentina and Pakistan, very large fiscal deficits and debt ratios (including debt with multilateral organizations) combine with ramping up inflation (and hyperinflation in the former). And in Tunisia, averting default has become tougher, especially since an agreement for an IMF program is yet to materialize. Argentina, Tunisia, and Sri Lanka (together with Türkiye) also share the dubious honor of having the highest ratios of external financing needs among countries in the sample. In these four countries, it’s hard to envision a return to prosperity without a major relaxation of the debt burden.

-

If one were to name “the most weakened country”, it would be China, which was in the top ten in the ranking in 2019 and fell to 18th in 2023. Local public finances have been strained by the country’s real estate crisis, which is reflected in the mounting public debt that now stands as the fifth highest among our sample of countries. Ongoing weakening of investors’ confidence could weigh on China’s slowdown, which would further impact the fiscal stance.

-

Although it is not among the most vulnerable countries, the Indicator does not deliver good news for Colombia. The country’s economic fundamentals deteriorated significantly from 2019 to 2023, which shows in the worsening of its position in the ranking from 16th to 23rd. Colombia’s external debt as a ratio of GDP sharply increased (by almost 20 percentage points) in that period, and inflation, while declining, has remained stubbornly high; indeed much higher than its Latin American peers using an inflation-targeting regime to control inflation.

-

Indonesia, Bulgaria, and Peru, the top three countries in the ranking, were also among the relatively strongest economies in 2019. Thailand is no longer in the top three, but, at the 6th position, it is still among the most resilient countries in the group.

-

Regarding the most improved countries, Ecuador and Angola stand out, but some clarification is needed. While Angolan indicators point to sustained improvements, Ecuador shows signs of a reversal of resilience.

-

Angola ranked very low in 2019, the 6th lowest position in the ranking. However, in my recent working paper, I flagged that the country had started a large fiscal adjustment in 2018 to address the unsustainable debt path. While the fiscal correction was not timely enough to prevent Angola’s sharp increase in default risk following the external shocks of the early 2020s, the continuation of these efforts has allowed a sharp reduction of the country’s external debt ratio and rating agencies have upgraded its sovereign debt liabilities. Although weakened by the quality of its institutions (a component of the Indicator), Angola now places close to the middle of the pack in the Indicator.

-

Ecuador’s position in the ranking has also improved significantly (it rose 11 places from the 5th worst position in 2019), but this reflects an erratic trajectory that needs to be monitored with care. The 2022 estimation of the Resilience Indicator (not shown here) placed Ecuador at an even higher position than in the 2023 ranking on the strength of a macro program initiated in 2021. However, important fiscal slippages and the weakening of the country’s institutional quality are reversing its gains in resilience. If this were to continue, it’s possible that the resilience indicator for 2024 will place Ecuador at a much lower position.

-

The usefulness of the resilience indicator is that it provides a warning signal that could help countries and the international community to prevent a crisis before it happens. By unpacking this straightforward resilience test, policymakers could identify where they should focus their efforts now, so they are better prepared if a worsening of global economic and financial conditions were to materialize.

[1] The Indicator has six components: (a) external financing needs; (b) external indebtedness; (c) fiscal balances; (d) government indebtedness; (d) deviation of inflation from target; and (e) institutional quality.

Nayke Montgomery was responsible for data collection, analysis and visualization, and research background

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.