Recommended

This post was first published on the blog of the Labor Mobility Partnerships (LaMP) project.

Current migration systems encourage migrants to take on debt and service providers to behave poorly, undermining the development impact of labor mobility. We propose a Migrant Welfare Fund that partners with impact investors to pay service providers for outcomes in connecting migrants to jobs, creating a rights-respecting and self-financing system.

The challenge

Mobility is one of the most powerful forces for poverty alleviation; migrants can increase their income by six to fifteen times simply by performing the same job in an overseas labor market. However, current international migration systems not only fail to realize the benefits but also, in some cases, cause considerable damage. Migrants often pay significant sums for the opportunity to work abroad. A report by a Verité, a US-based NGO, found that workers from Latin America and Asia paid service providers (i.e., agents) between US$3,000 and $27,000 to secure visas to the US, while the World Bank reports that South Asian workers regularly pay US$3,000 to $4,000 for jobs in Gulf Cooperation Council countries. These payments are made upfront, forcing migrants to either sell off assets or take on debt. The debt often comes with high interest rates, sometimes so high that migrants are required to continue working abroad way beyond their visa period simply to pay off these debts.

Worse still, migrants pay into this system without any assurance that they are getting what they’re paying for. Migrants often arrive in the receiving country to find that the job is not as expected, or the pay not what they were promised. Verité reported that 43 percent of the Nepali migrants they interviewed signed a different contract upon arrival at the receiving country with different terms to those they agreed to before migrating, and 36 percent never signed any contract. In the worst cases, the migrants arrive to find that there is no job.

What’s going wrong? First, the system of upfront payments creates no incentive for service providers to find quality employment for migrants. Second, there is a lack of transparency and accountability throughout the migration process—these are inherently cross-border operations, with different actors and different regulations on each side of the border, and no single entity responsible for ensuring the quality of the process from start to finish.

The solution often offered (indeed required by International Labour Organization Convention 181) is to make these services free for migrants. To date, zero-fee recruitment exists at small scale, with “ethical recruitment” firms placing small numbers of migrants relative to the rest of the recruitment industry, and in places where total bans on recruitment fees have been implemented have often pushed services into the black market.

Zero-fee recruitment does not solve the problem for three reasons:

-

It ignores migrants’ incentives and willingness to pay; they stand to make vast gains and view the fees as an investment.

-

It ignores the fact that there are real costs associated with the services, and (as is common in many contexts) if there is no other payer, it is impossible for a reputable organization to build a viable business model.

-

It relies solely on governments’ ability to regulate and enforce transactions over which they in practice can exert little control.

The proposal

We propose an alternative model—one that focuses on re-aligning incentives such that service providers are rewarded for supporting and sustaining migrants in quality employment, with controls and quality assurance throughout the migration process. Such a system should be preferred if it (1) results in better outcomes for the migrants, and (2) is financially sustainable.

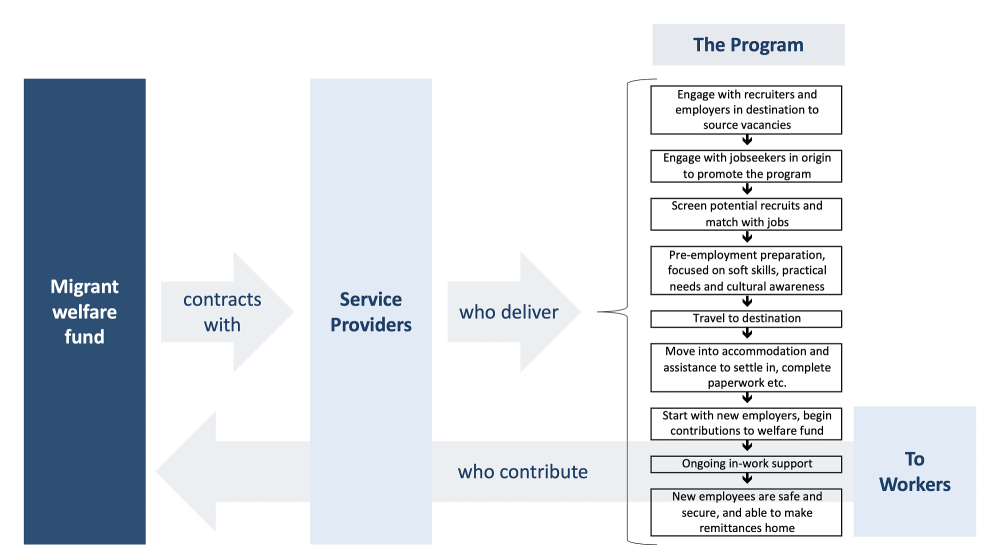

In our model, a rotating fund is established, covering the cost of job finding, migrant preparation/training, job/workplace audits and worker protection, settling in, and in-work support, as well as the necessary government institutions for protections and oversight. This Migrant Welfare Fund would be similar to those currently seen in some sending countries (such as the Philippines, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka) but with a number of key differences.

The Migrant Welfare Fund will have much wider scope and impact. It will not be tied to ancillary services only. It will facilitate large-scale labor migration. It will use outcome-based contracting to align the incentives of workers, employers, and governments.

The initial investment for the rotating fund and for its administration will be made by social investors. The services to migrants will be delivered by service providers contracted by the fund administration. Crucially, these providers will have outcomes-based contracts—with payments tied to the quantity and quality of jobs they help migrant workers to secure.

Migrants who successfully find and sustain quality employment through these service providers will contribute a percentage of their salary while abroad back into the fund. This contribution will repay the investors, cover the cost of ongoing in-work support, and fund the service providers to support the migration of future workers.

We anticipate that five years into the operation of a given fund, it would be able to support an annual outflow of 50,000 new migrant workers (growing to 100,000 in 10 years), with the fund administering around US$190 million of annual transactions. The total social investment per fund would be staged and is likely to be around US$50 million.

The advantages

Such a system would offer several advantages over existing models. It would:

-

Align the incentives of service providers with those of migrants: In this model, both service providers and migrants succeed when the migrant sustains quality employment abroad, thus aligning incentives rather than relying on regulations and enforcement, which work against the incentive structure.

-

Improve quality and demand-orientation of services: When providers are incentivized by outcomes, they are encouraged to take an individualized, localized approach to the needs of workers and employers and to innovate in the quality of their services.

-

Improve development outcomes for migrants: This model eliminates the issue of migrant indebtedness as workers no longer pay upfront, and never pay more than a pre-agreed percent of salary.

-

Build in transparency: By building in a long-term relationship between the migrant, the service providers, and the fund, we create the opportunity for feedback on the quality of support and of employment, which is absent in existing systems.

-

Link services across borders and enhance protection: By making one actor responsible for overseeing the entire migration process, we align the system across borders and build in protection for workers.

Next steps

For this system to be financially self-sustainable, it must be competitive with the existing market of service providers. This may prove difficult—in many countries, the market is very entrenched, to the point of even having political protection. We believe that over time, the lower costs, transparency, and quality of services would lead prospective migrants and employers to favor this model. However, in the short term, the dynamics are not easy to predict.

Because of this, we propose starting with a pilot contract, alongside work to establish the fund. A pilot program will aim to assist 3,000 workers to secure and sustain jobs overseas over the course of 18 months, with a cost of around US$6 million (to be funded by one or both governments or a donor). The pilot will build an evidence base on the outcomes possible in this delivery model. It will inform further refinement of the costing model and the structure of the Fund and its services, and build interest among social investors and service providers.

Several corridors have been identified as potentially promising and interested, and could be ready to pilot in 2020. Interested in partnering and/or seeing a detailed presentation on the Migrant Welfare Fund? Contact Rebekah Smith at rsmith@cgdev.org to learn more.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.