Recommended

WORKING PAPERS

Developing Asia as a region has experienced rapid growth over the past three decades. What have these episodes of sustained growth meant for income inequality? Has the region had “inclusive growth,” meaning growth which saw incomes rise without inequality increasing, or has inequality gotten worse? To address this query, we delve into the determinants of inclusive growth across 16 developing Asian countries*, comparing them with other developing and developed nations.

Our findings reveal that inclusive growth is more likely to occur in developing Asia when direct taxation and social benefits are redistributive in nature. Moreover, higher per capita expenditures on healthcare and education contribute to this inclusivity. Well-targeted social benefit programs tailored to lower-income segments of population emerge as a crucial driver of inclusive growth.

Comparative analysis: developing Asia versus other regions

Noteworthy parallels and distinctions emerge in the determinants of inclusive growth between Asia and the economies of other developing regions, as well as between developing Asia and the more developed Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) region. Just as it is in the countries of developing Asia, higher government spending on public health is associated with an increased likelihood of inclusive growth in other developing nations and LAC. Furthermore, education spending emerges as a significant factor in driving inclusive growth in other developing countries.

Nevertheless, specific differences set developing Asia apart from these regions. Notably, fiscal redistribution enhances the chances of inclusive growth in countries in developing Asia, contrary to developing countries overall, where it tends to hinder such prospects. This favorable outcome for developing Asia can be attributed to its wider implementation of social insurance and assistance programs, especially in the Central Asia region. These findings also underscore that the design of social protection initiatives in developing Asia has a relatively muted negative impact on labor market efficiency and equitable distribution of growth benefits among lower-income households.

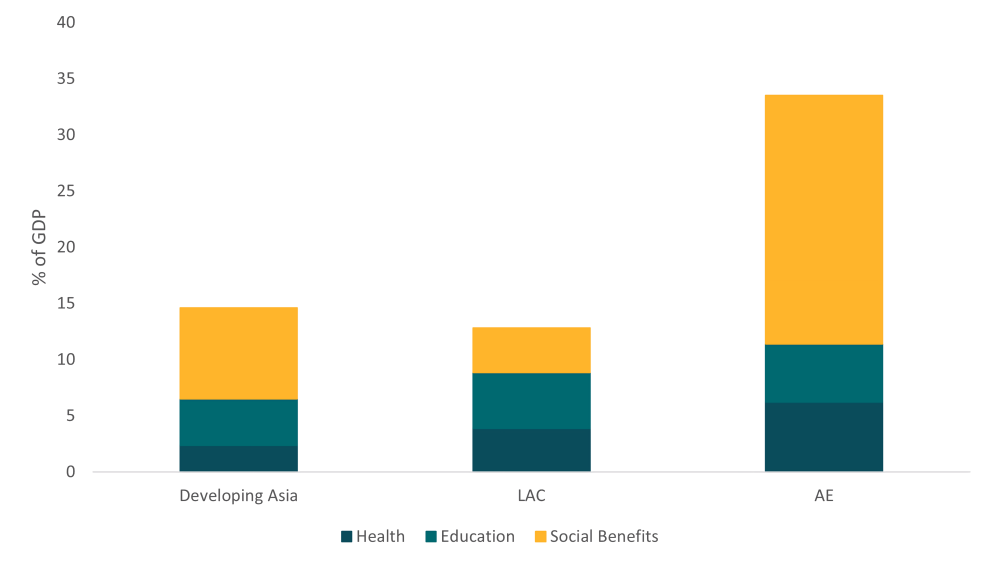

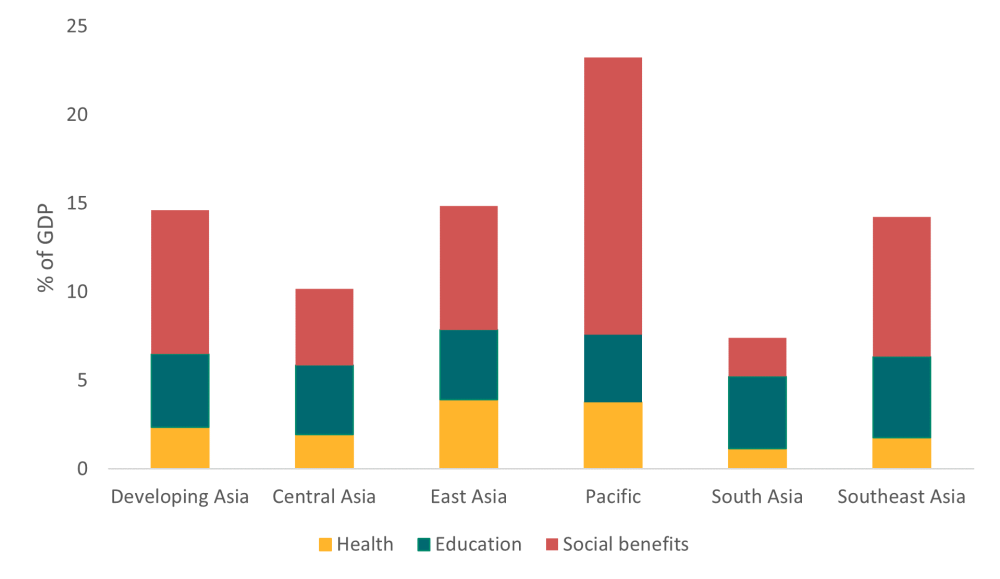

Outlays on social benefits, health, and education in developing Asia

A comparison of spending patterns in developing Asia vis-a-vis advanced economies and LAC reveals interesting trends. As shown in Figure 1, relative to LAC, developing Asia allocates more resources to social benefits and less to education and healthcare. However, spending levels substantially lag that of advanced economies, with social benefits lagging the most. Noteworthy differences across different categories of social spending (health, education, and social benefits) are observed within developing Asian regions, with higher health expenditures in East Asia and the Pacific, and lower health spending in South Asia, except for education (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Government expenditure by function across country groups, 2014–2018

AEs = advanced economies, GDP = gross domestic product, LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean.

Sources: Authors’ calculations using World Economic Outlook database; World Development Indicators; and, for advanced economies spending on social benefits, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Figure 2. Social spending by region in developing Asia, 2014-18

Sources: Authors’ estimates using World Economic Outlook database and World Development Indicators accessed August 2021

In developing Asia, income inequality generated by market forces (that is, the level of income inequality in a country before taking into account the impact of government taxes and social benefits) is lower than it is in LAC and advanced economies, as indicated by the lower Gini coefficient the first column of Table 1. Taxes and social benefits, however, achieve only a modest level of redistribution in developing Asia, reducing the Gini coefficient by about 4 percentage points, compared to a reduction of about 18 percentage points in advanced economies. This is because of the limited use of the personal income tax and property taxes in developing Asia, as well as the modest size of social benefits. While the targeting of social benefits in developing Asia is better than many other developing regions, it is still limited, dampening its potential to redistribute income.

Table 1. Redistributive effects of fiscal policy

(latest available data)

|

Gini Coefficient, Market |

Gini Coefficient, Net |

Redistributive Effect of Fiscal Policy (Market–Net) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Developing Asia |

42.7 |

38.4 |

4.2 |

|

Latin America and the Caribbean |

48.1 |

45.4 |

2.6 |

|

Advanced economies |

48.3 |

30.4 |

17.6 |

Note: Calculations based on latest available data for each country over the years 2010–2020. Developing Asia comprises 38 countries, Latin America and the Caribbean comprises 26 countries, and advanced economies comprises 30 countries. The redistributive effect of fiscal policy is the difference between the market income Gini coefficient and the net Gini coefficient.

Source: World Income Inequality Database.

In summary, we find that developing Asia does a better job than other developing regions in the targeting of its social benefits, which is reflected in the positive impact of fiscal redistribution on achieving inclusive growth. Nonetheless, low levels of spending and limited targeting of benefits have blunted the full redistributive potential of these outlays. Expansion of both the coverage and targeting of social assistance programs could help make social spending more conducive to inclusive growth.

* Only 16 countries are included in the econometric analysis because of data availability. They are: Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, Sri Lanka, India, Indonesia, Lao P.D.R., Malaysia, Maldives, Nepal, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Fiji, China, and Mongolia.

Benedict Clements is a professor at the Universidad de las Américas in Ecuador.

Joao Jalles is an Associate Professor at the University of Lisbon.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Aleksandar Todorovic / Adobe Stock