Recommended

Globally, up to 40 percent of money spent on healthcare is wasted due to inefficiencies in national healthcare systems. The reasons for this include the funding of inappropriate health interventions, over treatment by clinicians, failure to coordinate care across providers, pricing failures, administrative waste and fraud. Such inadequate and inefficient spending not only leads to greater out-of-pocket expenditure for patients, but can also hinder progress towards Universal Health Coverage (UHC).

India has recently taken a step closer towards UHC by creating the world’s largest national health insurance program titled the Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (AB-PMJAY). The aim of this scheme is to cover the bottom 40 percent of the India population for up to USD 68,000 (₹5 lakh) per family per year via cashless health benefit packages for all types of secondary and tertiary healthcare. To maximise health benefits from AB-PMJAY scheme, there is a need to ensure resources are not wasted and healthcare delivery through the scheme is efficient, equitable and quality assured. This will help tackle catastrophic health expenses that push more than 60 million people into poverty every year in India.

Strategic purchasing—‘the continuous search for the best interventions to purchase, the best providers to purchase from, and the best payment mechanisms and contracting arrangements to pay for such interventions’—can help address inefficient spending and allocate health budget more effectively.

Strategic purchasing can help address inefficient spending and allocate health budget more effectively.

In this blog, we explore three key actions linked to strategic purchasing that India’s AB-PMJAY scheme can apply by leveraging its influence as a major purchaser of services and goods in the country. These same actions are readily generalizable and can replicated by other jurisdictions to save money, improve health and accelerate a country’s journey towards UHC.

1 . Establish an internal Office for Strategic Purchasing

Purchasing agreements in most countries are complex, political processes involving multiple stakeholders, fund flows and governance requirements. Supporting good governance, fair competition and mitigating corruption in purchasing decisions are integral to deriving efficiencies within the healthcare system. However, responsibility of purchasing decisions in healthcare are often left to individual hospitals or healthcare providers who are either uninformed or have little capacity to institutionalise strategic purchasing.

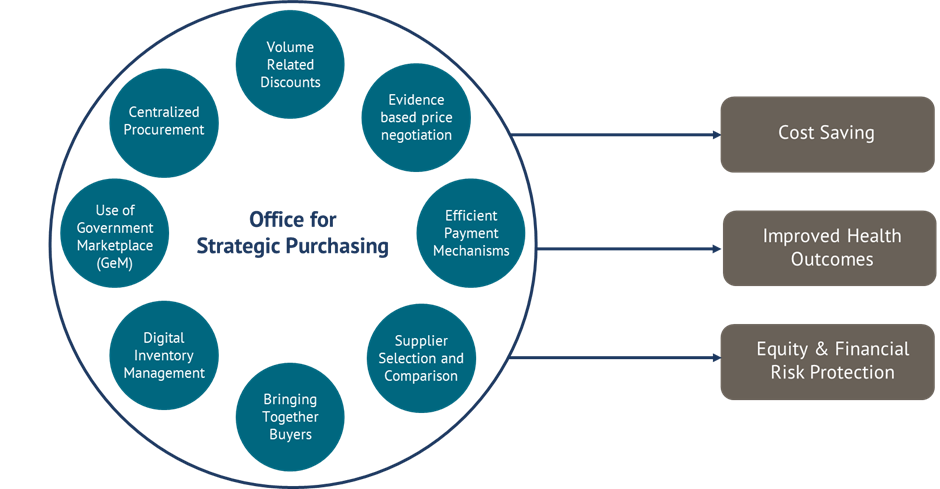

Centralized procurement in the form of an “Office for Strategic Purchasing'' offers a good approach to address this issue. This office would have to have a clear mandate and should establish consistent and predictable institutional processes and structures to make purchasing decisions in a strategic, evidence-based and transparent manner.

Figure 1. The different functions of work an “Office for Strategic Purchasing” is responsible for, and the potential health and economic gains incurred from such functions.

In England, most healthcare goods (including drugs, equipment and PPEs etc.) are bulk-purchased centrally and distributed to providers by NHS Supply Chain, which manages around 4.5M orders a year and aims to carry 80 percent of all NHS purchases by 2022. In Norway, the Drug Procurement Cooperation makes mass procurement of drugs worth USD 93,75,320 million, annually, with an average volume related discount of 30 percent compared to list prices in neighbouring countries.

In India, the National Health Authority (NHA), which is responsible for AB-PMJAY, has a window of opportunity to establish an “Office for Strategic Purchasing''. This office could engage in multiple actions related to purchasing both goods and services, including evidence informed pooled procurement—which would allow the NHA to negotiate lower prices and simplify quality assurance mechanisms. The Office of Strategic Purchasing could also offer centralized framework contracts where long-term agreements are secured and managed on behalf of different states, institutions or medical specialties. Finally, it can also be responsible for supplier selection guided by systems like AB-PMJAY Quality Certification, which considers the ability to deliver guaranteed services, workforce availability, supply chain challenges and compliance with data exchange systems.

2 . Use health economic evidence to ensure value for money and quality in healthcare delivery

Evidence-informed decision making is a founding principle of UHC and strategic purchasing. Purchasing decisions should incorporate crucial evidence on disease burden, country-specific goals and existing capacities or availability of services within healthcare systems.

Health economic evidence helps mitigate the challenges of goods or services being priced too low or too high. For example, if prices are set too low, it can result in poor quality of services, informal out of pocket payments or denial of service to seriously ill patients. Setting prices too high can jeopardise efficiency, affordability and sustainability of the healthcare system. Health economic evidence derived from traditional or adaptive health technology assessment (HTA) approaches can be used to signal the price at which a product should be procured and will be cost-effective or cost-saving for the national health insurance scheme. For example, the Government of Punjab state of India negotiated down the price of safety engineered syringes using HTA evidence. Similarly in 2016 in Thailand, a price negotiation working group within the government negotiated down the prices of intraocular cataract lenses, essential drugs, and coronary stents, saving around USD 257 million.

Economic evidence incorporated within pre-defined quality indicators based on local Standard Treatment Guidelines (STGs) can also ensure value for money and quality in healthcare delivery. Contracts can be designed to pay for performance, and include disincentives for not adhering to agreed standards of quality care. Here, the ABPMJAY scheme is primed to initiate monitoring of quality indicators which can aid in establishing supplier comparisons or star ratings.

Health economic evidence should also inform what is included in or excluded from health benefits packages. AB-PMJAY has already been using economic evidence and costing data to update their Health Benefit Packages list and inform the reimbursement rates decided for specific health benefits packages. This minimises out-of-pocket expenditure and financial catastrophe for users of AB-PMJAY, and could ensure better uptake of the scheme as healthcare providers are reimbursed appropriately.

The proposed Office of Strategic Purchasing within the NHA could actively engage with Health Technology Assessment in India (HTAIn) and its network of Regional Resource Centres to generate and use health economic evidence in price negotiations, the development and implementation of Standard Treatment Guidelines and health benefit package updates.

3. Digitise strategic purchasing and monitor capacity, performance and quality of healthcare service delivery

Digitalization of inventory management systems can help systematic distribution of drugs, devices and other centrally procured goods to reach all healthcare delivery providers in time. For example, in Tanzania and China, the Jazia Prime Vendor System and China’s distribution market reforms have significantly improved drug availability and access for their citizens.

In recent years, India has been championing the National Digital Health Mission (NDHM), housed within the NHA. The NDHM's mandate is to create a comprehensive digital health infrastructure that connects patients, providers, and other stakeholders to improve health outcomes. It aims to also develop a single updated repository of all the doctors in the nation, with their qualifications, and all the health facilities across India. In essence, the goal of this initiative is to increase transparency and the exchange of information between public and private sectors, facilitate patients’ access to providers and follow-up care (including telehealth), securely store data (and set data security standards), and improve provider accountability. India already has an established government procurement portal, the Government e Marketplace (GeM) housed by the Ministry of Commerce, and a platform to monitor the capacity, performance and quality of healthcare service delivery in real time (especially in areas like reproductive health, maternal and child health and immunisation), the Health Management Information System (HMIS).

The NHA, which houses the NDHM and AB-PMJAY, should encourage collaboration and alignment between these existing systems—which can then be optimized and used to facilitate the seamless procurement, distribution and monitoring of goods or services to healthcare providers in the country.

The proposed Office of Strategic Purchasing could actively use the GeM and develop streamlined trading networks that make negotiating, settlement and delivery more efficient in the AB-PMJAY scheme. The office, in collaboration with the NDHM, could also start using the HMIS and engage other bodies like the Central Medical Services Society (an autonomous public body for procurement and supply chain management of health sector supplies in India housed within the Ministry of Health) to digitally monitor capacity, performance and quality of healthcare service delivery within the AB-PMJAY scheme.

Conclusion

Universal Health Coverage not only requires adequate funding but also necessitates a strategic approach to purchase goods and services to prevent waste and maximise efficiency. Useful methods in the strategic purchasing toolkit could be pooling of resources, evidence guided decision making, efficient procurement and payment mechanisms, augmented with robust quality assurance systems and use of HTA. Responsibility of strategic purchasing must lie with an autonomous and independent office within the public payer that is transparent, accountable and has the necessary governance mechanisms to facilitate such methods.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.