Recommended

Event

Global Health Supply Chains: The Role of Private Wholesalers & Distributors in Improving Access to MedicinesIn many LMICs, the market of pharmaceutical wholesalers and distributors is extremely fragmented, with too many intermediaries and small, inefficient firms. China and Tanzania provide two examples of reforms.

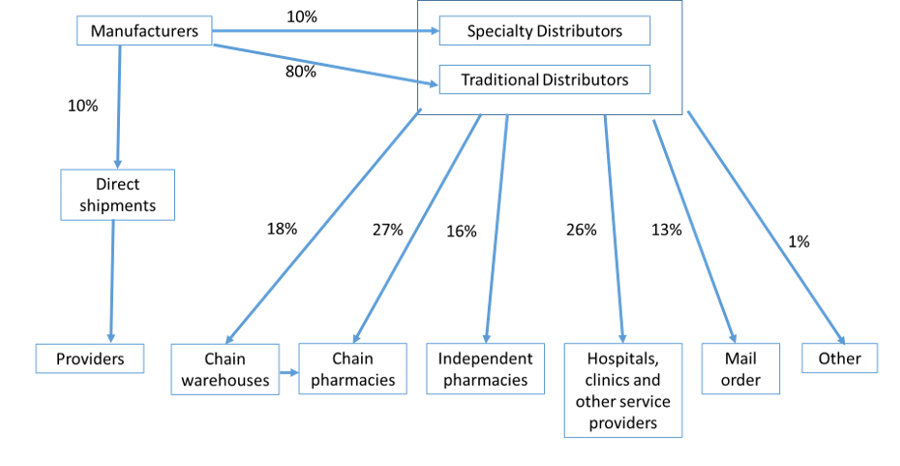

Pharmaceutical distribution around the world is organized in slightly different ways, but in all OECD countries private wholesalers and distributors make frequent (daily or sometimes twice a day) deliveries to supply medicines and health products to hospitals, clinics, and retail pharmacies. Some hospitals and retail pharmacy chains buy directly from manufacturers and receive deliveries through manufacturer-appointed logistics companies, but most of the drugs distributed in the US and EU are delivered by private wholesalers and distributors.

Figure 1. US pharmaceutical distribution channel.

Source: Yadav and Anupindi 2018. Case study in FIP Report on Pharmacists in the Supply Chain, 2018

Pharmaceutical wholesaling/distribution is a highly consolidated industry in most OECD countries. In the US, for example, three large wholesalers/distributors—McKesson, Cardinal, and Amerisource-Bergen—control over 90 percent of pharmaceutical distribution.

Typically, we assume that competition in the marketplace is good for consumers and good for industry-level productivity. It forces “creative destruction” where new businesses (and business models) replace outdated ones. In many areas of the healthcare market, a high degree of market concentration is indeed a key concern as it may be a significant contributor to higher prices. However, in pharmaceutical wholesaling and distribution, a reasonable degree of concentration may in fact be beneficial to consumer welfare.

The benefits from a more consolidated pharmaceutical wholesaling/distribution industry arise from a range of factors. The share of fixed costs and the value of the product relative to its weight/volume are both quite high in the pharmaceutical distribution business. Providing “fine-mesh” distribution reach to every corner of a geographically large market (such as the US) requires significant capital investments in distribution warehouses and information technology. It also requires fixed investments in skill development in the areas of procurement, forecasting, distribution, logistics, and financial management. As a result, there are large economies of scale in pharmaceutical wholesaling and distribution.

Before the new wave of highly automated company-run distribution centers started emerging in the e-commerce sector in the last decade, the most automated warehouses were those run by one of the large pharmaceutical distributors. Decades of investments in information technology and warehouse automation have made pharmaceutical distribution centers run by large wholesaler/distributors the hallmarks of efficiency. Pharmaceutical wholesalers and distributors operate with very thin gross margins. US wholesalers and distributors are reported to have margins of 3.7 percent across all drugs, although it varies significantly by generic or branded product. Gross margins of European distributors fall within the same range. Thus, consolidation in the wholesaling/distribution segment isn’t necessarily increasing markups but is in fact improving efficiency. (That said, there may some potential downsides when the wholesaler market reaches an extremely high degree of consolidation.)

Wholesaling and distribution in low- and middle-income countries

That’s the case for high-income countries, but let’s switch gears to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). In most LMICs there are too many wholesalers, meaning the market is too fragmented. Wholesalers/distributors have to recover their fixed costs over a relatively small volume base. Sub-scale wholesalers/distributors either shirk from making fixed capital investments in warehousing, IT, skill development, and transport infrastructure; or charge higher gross markups. Few wholesalers/distributors have national distribution reach and a multi-layered channel emerges in which a national wholesaler sells onward to a sub-wholesaler, who then sells to another sub-sub-wholesaler and so on. In some regions, there can be as many as six intermediaries to reach the retail pharmacy or clinic. Each channel intermediary charges a markup, creating a much wider wedge between ex-manufacturer price and the retail price. Multiple channel intermediaries also create challenges related to accounts receivable collection.

Figure 2. Lack of national distribution reach creates additional layers in the distribution networks (and additional markups) of most low- and middle-income countries.

LMIC drug regulators who are stretched for resources find it harder to audit and enforce quality in such a fragmented and multi-tiered wholesaling/distribution market.

The structure of the wholesaling/distribution market in many LMICs, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, is detrimental to patients, payers and regulators on the dimensions of availability, affordability, and quality.

Historically, national policymakers have tried to address this issue by creating a single government-owned national wholesaler/ distributor (often called Central Medical Store to reflect the central planning era in which they were created). While in theory this may create the economies of scale which are important for efficient distribution, government-run distributors are often fraught with management and technical inefficiencies. Despite having economies of scale, they lack investments in developing core supply chain skills, management techniques, and IT infrastructure. More generally, the lack of competitive pressure leads to the government run supply agencies falling behind on productivity improvement, technological advances and they start exhibiting many of the problems associated with X-inefficiency of a public sector agency.

How can the wholesaler market be reformed? The examples of two countries show possible solutions to the excessive fragmentation of the market.

China’s distribution market reform

Until the 1990s China had a similar wholesaling market structure, with over 30,000 pharmaceutical wholesalers/distributors, very few of which had national reach. The resulting system had many layers of wholesalers and regional specific sub-wholesalers with challenges similar to those today’s LMICs are facing. However, a decade of reform has led to some degree of consolidation in China’s pharmaceutical wholesaler/distributor market. The regulatory requirements for registering as a wholesaler include warehousing compliant with the Good Distribution Practices certification, cold room storage, and an IT system to track product flow. Those requirements created the conditions for market consolidation. A few large firms such as Sinopharm, China Resources, and Shanghai Pharmaceuticals have emerged as national distributors and the number of smaller, sub-scale distribution firms has decreased. In addition, health reforms in Fujian province included an approach to reduce layers in the distribution system through a “two-invoice” system. This model, which has since been rolled-out nationwide, has made the system more transparent and flatter and forced wholesalers/distributors to have national reach, resulting in further market consolidation.

Figure 3. Overview of the two-invoice system in China.

Tanzania’s Jazia Prime Vendor system

Tanzania has created a system which circumvents some of the problems resulting from excessive fragmentation of the wholesaler market through selective contracting by payers. Under the Prime Vendor program, a district selects a wholesaler, which supplies medicines that are either not available or low in stock at the government-run central supply agency (the Medical Stores Department) directly to districts. Prices are pre-negotiated with the selected wholesaler and quality control checks are carried out. The district pools the orders from health facilities and places an aggregate order to the selected wholesaler . When the program was in an early phase, it led to an increase in the availability of tracer medicines from 69 percent in 2014 to 94 percent in 2018. The approach has since been expanded nationally, allowing facilities to purchase supplemental drugs from pre-selected private wholesalers.

The Prime Vendor program selects a smaller number of better-performing wholesalers who get a share of the market demand from government health facilities. The performance of these wholesalers is monitored quarterly using a composite of performance indicators related to on-time delivery, shelf life of delivered products, and overall customer satisfaction. If those indicators are robustly measured and transparently reported, it would contribute to a consolidation of the market towards wholesalers who are able to deliver better performance and win the Prime Vendor contracts. There are some unanswered questions regarding the long-term governance and market impact of the Prime Vendor system, but it has demonstrated that health facilities can pool their demand and obtain good prices and delivery terms from private wholesalers.

Figure 4. Overview of the Prime Vendor program in Tanzania.

Creating a healthier wholesaler/distributor market: Ideas for discussion

The cases of China and Tanzania are by no means the only examples where private wholesalers/distributors have provided services in health product supply chains in LMICs. There are numerous examples of governments revamping their medicine supply system by engaging with private actors, but these are two illustrative ways to solve for the excessive fragmentation in the wholesaler market. More recently, new technology-based distributors or value-added service providers have entered the market in many LMICs. Their business models are built around creating new ways to work around the excessive fragmentation in the wholesale and retail market.

There is an ongoing debate on whether direct health facility financing through results-based financing or other means can increase the ability of health facilities to purchase medicines directly from private wholesalers. Some studies show that the availability of medicines improves as a result of direct facility purchasing. However, there are continuing concerns about the prices obtained and the quality of products purchased. If there was a way to ensure the quality and system maturity of private wholesalers, along with a way to create framework price contracts, programs like Tanzania’s Jazia system could become a strong complementary source of supply to health facilities when the government-run medical supply agency is unable to provide supplies. Such programs may also create some competition for government medicine supply agencies and perhaps help reduce some of their X-inefficiency. Coupling this with barcode and other IT tools to verify stock receipt and flow will further bolster the effectiveness of wholesaler supply programs. The example of China points to the possibility of a regulatory policy lever: raise the regulatory standards for registering wholesaler and explore other policy tactics like the two-invoice system. Perhaps, it not about choosing one or the other but designing a comprehensive program which can in the long-run create a healthier wholesaler/distributor market: a wholesaling/distribution market which can better serve the needs of the health system and provide frequent deliveries of a full line of high-quality essential medicines.

This post doesn’t cover all the aspects of the market structure of pharmaceutical wholesaling and distribution. But hopefully the arguments above illustrate that engagement with private wholesalers and distributors is an area which deserves far more attention than what it has historically received in the design of global health supply chains.

If you are interested in an engaging and interactive discussion around this topic, join us in-person or via webcast for an event on Monday, Jan. 27th from 3:30 to 5pm. You can find details and registration information here.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.