Recommended

In April 2022, the IMF board approved the establishment of the Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST) to provide financial support to countries addressing two key long-term structural challenges, climate change and pandemic preparedness. Almost a year late, the board has approved RST-supported programs for five countries: Bangladesh, Barbados, Costa Rica, Jamaica, and Rwanda, with disbursements starting this month for Costa Rica. In a new paper, we explore the operations of the Resilience and Sustainability Facility (RSF) and draw important lessons to make its lending more effective in the future. Our paper complements earlier CGD analyses exploring the design of RST programs and advising on how RSF programs can address pandemic preparedness.

We conclude that future RST programs could be made more effective through improvements in five areas: ensuring that reform measures are sufficiently deep to bring about a tangible change; making sure that the overall conditionality in RST-supported and accompanying program is not unduly excessive, particularly in low-capacity countries; monitoring climate-related investment spending in countries receiving RST support; increasing climate diagnostic support in countries seeking RST programs; and including measures to prepare countries for future pandemics.

Current RSF arrangements

To understand RSF operations, it helps to first review a few key technical details:

- 143 countries are eligible, including all low-income countries (LICs), all developing and vulnerable small states, and lower middle-income countries (LMICs)

- Access is limited to 150 percent of a country’s IMF quota or up to SDR 1 billion

- Loans have a long maturity of 20 years with a grace period of 10½ years and are provided at highly concessional terms

- LMICs pay a higher interest rate margin than LICs

- RSF is funded through voluntary contributions of SDRs, loans and grants, or any freely usable currency

- $20 billion of funding has been received of the RSF’s $42 billion goal; the IMF expects remaining contributions soon

- Any country receiving RSF financing should have an accompanying IMF-supported program with “upper credit tranche” quality policies

The RSF and accompanying programs have committed over SDR 7 billion to the five countries; SDR 2.5 billion of this is from RST. So far, all reform measures (RMs) in RSF programs—measures that countries are required to implement over the program period—are in the area of climate change, with none in pandemic preparedness. RMs in current RST programs number between 10 and 13, with a median of 12.

Overall number of conditions

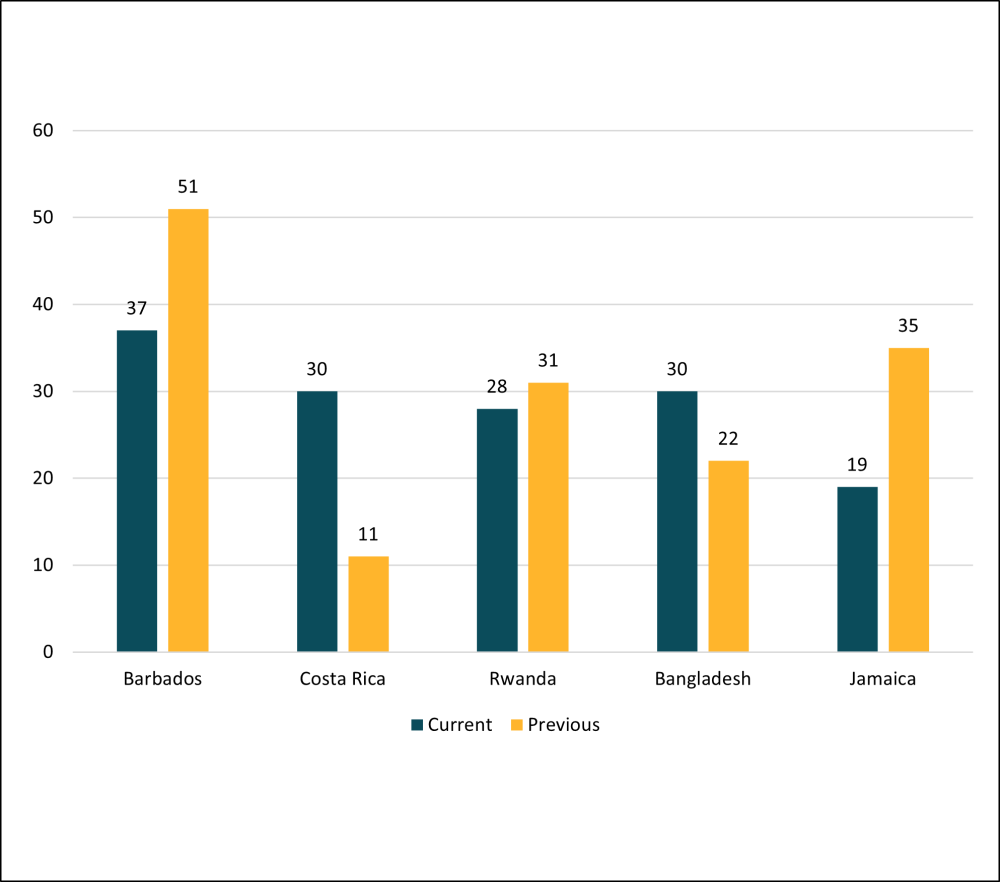

The overall number of conditions in RST-supported programs combined with accompanying IMF programs have increased in two countries (Costa Rica and Bangladesh) compared to previous IMF-supported programs (Figure 1). They declined in two countries (Barbados and Jamaica) and remained broadly unchanged in Rwanda. Countries with relatively weak implementation capacity may find it difficult to implement a larger number of conditions during the program period.

Only one country has cross-conditionality between the RST-program and accompanying program. In Bangladesh, the periodic adjustment in petroleum prices is both a structural condition (SC) in the accompanying program and an RM in RST program.

Figure 1. Conditions in current and previous programs

Sources: RST, EFF, ECF, PLL, SBA, and PCI documents.

Note: Prior programs are 2018 EFF for Barbados, 2009 SBA for Costa Rica, 2019 PCI for Rwanda, 2012 ECF for Bangladesh, and 2016 SBA for Jamaica.

Nature of climate conditionality

An RST-supported program is expected to focus on five key areas: climate mitigation, climate adaptation, climate finance, public investment management (PIM), and public financial management (PFM). Table 1 gives the share of each in five approved programs.

Table 1. Key climate action areas in five RST-supported programs

|

Country |

Climate Adaptation |

Climate Mitigation |

Climate Finance |

Public Investment Management |

Public Financial Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Barbados |

2 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

3 |

|

Costa Rica |

0 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

|

Rwanda |

0 |

0 |

4 |

3 |

6 |

|

Bangladesh |

0 |

0 |

6 |

2 |

3 |

|

Jamaica |

0 |

3 |

5 |

1 |

3 |

|

Total |

2 |

9 |

21 |

8 |

18 |

When combined with PIM, PFM broadly defined dominates with slightly less than half of all measures. In this respect, RST-supported programs are no different from other IMF-supported programs in low- and low-middle income countries, where PFM conditionality has been dominant. This indicates the potential for cross-conditionality between an RST-supported program and the concurrent IMF arrangement. PFM conditionality played a key role in IMF programs designed to facilitate debt relief to heavily indebted low- income poor countries in 2000s.

Composition of conditions

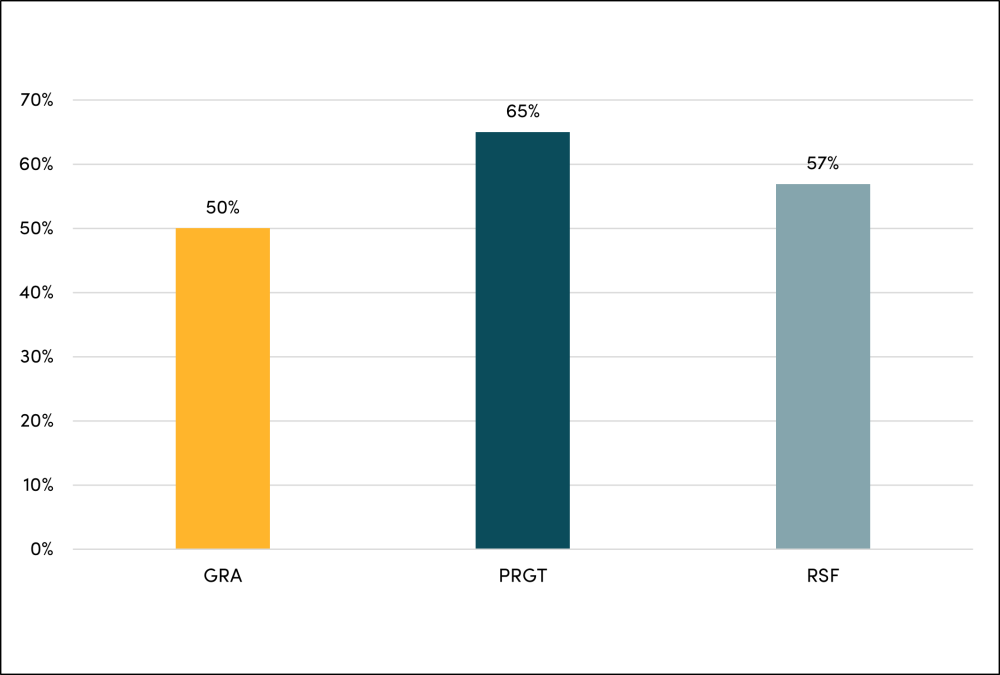

The composition of RMs in RST arrangements is like SCs found in other IMF programs supported by GRA (General Resources Account) and PRGT (Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust) resources. As found in prior research, fiscal SCs dominate GRA and PRGT-supported programs, with more than two-thirds of all conditions classified as fiscal (Figure 2). A similar picture emerges in RST-supported programs’ RMs—excluding SCs of accompanying programs, where fiscal RMs constitute three-fifths and financial sector RMs make up one-fourth. The most common fiscal RMs call for incorporating fiscal risk resulting from climate change into the budget and strengthening guidelines for project selection. Financial sector RMs center on climate proofing of the financial system.

RST-supported programs provide a list of RMs without highlighting their relative importance in the program design. The lack of prioritization of RMs is an important omission because resources from RST are disbursed only after the completion of a successful program review and not at the time of program approval. In the absence of prioritization, it would give the IMF undue leeway on whether to conclude the review.

Figure 2. Share of fiscal SC/RM in total SC/RM

Sources: Gupta (2021) based on 131 programs implemented during 2008 and 2019; various RST documents.

Depth of conditions

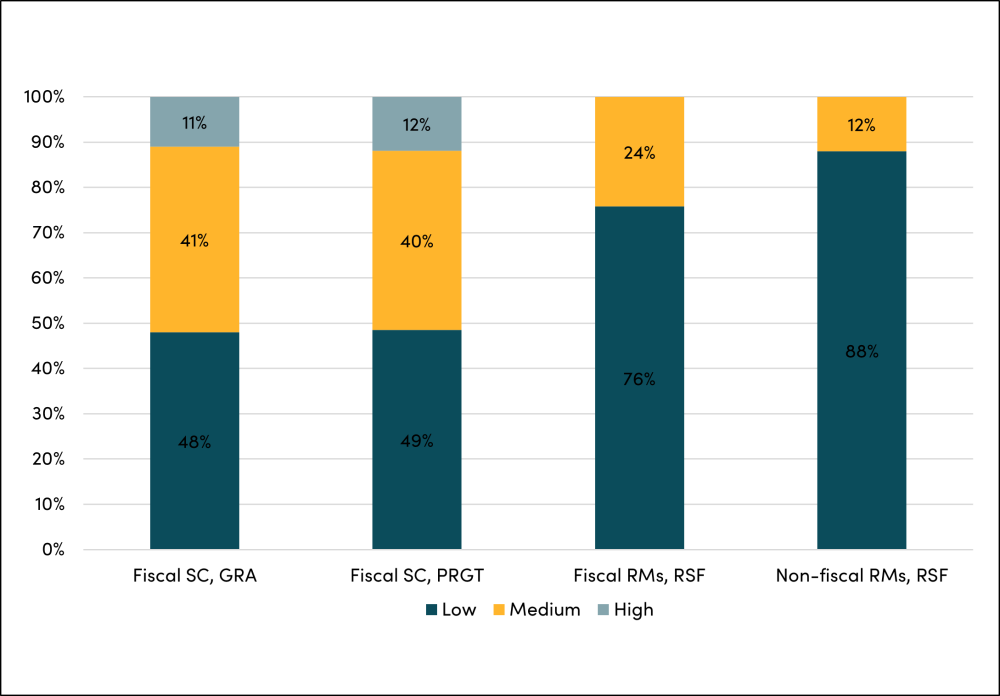

Following the methodology used in IMF’s 2018 Review of Program Design and Conditionality, RMs in RSF programs can be classified as high-, medium-, or low-depth measures. High-depth reforms entail permanent institutional changes, such as legislative changes (parliamentary approval of the new VAT law), or have a long-lasting impact (e.g., civil service reforms). Medium-depth reforms lead to a significant change but are one-off in nature (e.g., budget approval or one-time change in tariff/tax rates). Finally, low-depth reforms do not bring about a change by themselves but are steps toward a change that can pave the way for more critical reforms.

In contrast to 131 GRA and PRGT-supported programs implemented during 2008 and 2019, RST-supported programs are dominated by low-depth measures, which constitute around 80 percent of fiscal RMs and 90 percent of non-fiscal RMs. The rest are medium depth (Figure 3). Given the long-term nature of the climate challenge, the fact that these are initial steps by countries to address climate change, and the probable lack of country capacity to implement more ambitious mitigation measures, this result is not surprising. However, the large share of low-depth measures implies the need for follow-up in the RSF or other accompanying programs and provide increased diagnostic support to identify relatively deeper measures.

Figure 3. Fiscal SC/RM by depth

Sources: Gupta (2021) based on 131 programs implemented during 2008 and 2019; various RST documents.

Need for greater diagnostics?

There are three key diagnostic tools that assist RST countries in identifying policy and capacity gaps in preparing for climate transition: the IMF’s Climate Public Investment Management Assessment (C-PIMA) and Climate Macroeconomic Assessment Program (CMAP) and the World Bank’s Country Climate and Development Reports (CCDRs).

Of the five countries currently receiving assistance under RST, three (Costa Rica, Jamaica, and Rwanda) have a C-PIMA and two (Bangladesh and Rwanda) have a CCDR. None has utilized a CMAP. Only Rwanda has received input from both C-PIMA and CCDR, while Barbados have received neither.

In addition to IMF-Word Bank diagnostics, RSF programs have relied to some extent on national climate-related policies to formulate RMs. For example, Bangladesh’s RMs draw from its National Adaptation Plan and Barbados’ RMs draw from its Economic Recovery and Transformation plan.

The lack of diagnostics could contribute to the prevalence of lower-depth RMs. Additionally, even when well-designed processes are put in place as envisioned under RSF reform conditions, countries may not implement them in practice, as observed in PFM. This could lead to full climate benefits not being realized from RM implementation.

Initial lessons

The RST is a welcome addition to the IMF’s lending toolkit for providing long-term financing at highly concessional terms to developing countries to address the structural challenges of the climate transition and pandemic preparedness. However, the limited experience so far suggests ways in which the operations can be strengthened to better achieve program objectives. Here are five suggestions:

-

Pay greater attention to depth of program measures. The share of low-depth RMs is almost double in RST-supported programs as compared to SCs of a typical GRA and PRGT-supported program. Since the objective is to achieve more durable institutional and policy changes in climate transition and pandemic preparedness, it is necessary to move to a larger share of relatively greater depth measures in subsequent RST or other IMF-supported programs. At the same time, RMs should be prioritized to allow a smooth review of RST-supported programs at the time of disbursal of funds.

-

Pay attention to capacity to implement in conditionality design. Our analysis found that the overall conditionality in IMF-supported programs has increased in some countries. This raises the question if these LICs or LMICs have the capacity to implement the larger number of conditions. The number of conditions must be kept in mind especially as countries begin to incorporate pandemic preparedness RMs. Some climate reform conditions may need to be dropped, and a greater use of cross-conditionality between an RST and other IMF programs, particularly in the PFM area, may help reduce workloads and simplify program monitoring.

-

Monitor climate-related public investment. Under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative, the World Bank and IMF boards required countries to regularly report the budget share of poverty-reducing spending in total spending to ensure resources released as a result of debt relief were used for increasing poverty reducing spending. A similar approach could be considered for countries drawing RST resources whose key purpose is to increase investment in climate transition. RSF countries would be required to report the budget share of climate-related investment in total public investment. This should not be a constraint since existing IMF-supported programs require reporting certain types of spending during the program period.

-

Increase support through climate diagnostics. While perfect alignment of diagnostics with program support is difficult to achieve, increased coordination between the two would help countries reap full benefits from the financial support through RST.

-

Focus also on pandemic preparedness. Pandemic preparedness is a long-term priority with strong global public good characteristics. There is little basis to wait for health preparedness guidelines to be developed together with the World Bank and WHO. There is sufficient understanding of policy changes needed to strengthen existing health systems, particularly at the primary healthcare and community level, that countries could implement at this stage. Such measures are needed not only to prepare for the next pandemic, but also to strengthen existing health systems to deliver essential routine services.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Tada Images / Adobe Stock