Donors give arbitrary income lines a lot of power in determining funding allocation. This issue is particularly true in the health sector, where organizations like the GAVI Alliance (GAVI) and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM) determine how much support a country will get based on its income status. But the income level of a country alone should not make a country ineligible or less eligible for donor funding – especially when estimates of such income levels can change overnight.

Due to new purchasing power estimates released this week by the International Comparison Project, GDP per capita numbers have indeed changed overnight. And that means that country income classifications –and aid eligibility designations – will be on the move too. As a result, less health aid will go to the countries that need it most.

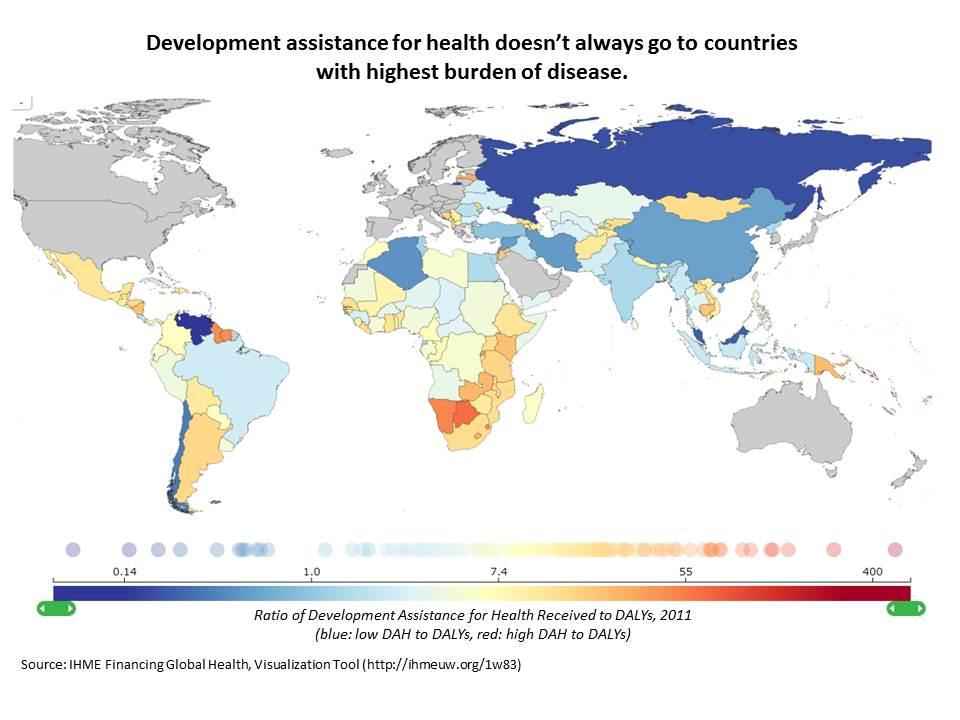

Disease burden is concentrated in countries now classified as middle-income. Because of this income classification, these countries are less likely to be eligible for health aid. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation’s recent report finds that many countries with the highest disease burdens do not receive most development assistance for health. They write: “of the countries with the top 20 DALYs, only 13 are among the top 20 recipients of [aid].”

Both GAVI and the Global Fund are grappling with how to adjust to this (rapidly) changing landscape.

Since November 2009, GAVI has implemented a “graduation policy” for countries whose GNI per capita crosses an eligibility threshold. That is, a country can no longer apply for new vaccine or cash-based program support once they moving past a certain income line.[1] Depending on the specific vaccine, countries have access to the lower GAVI price for a period of time after graduation.[2] But there are cases where GNI per capita of a graduator looks pretty close to an eligible country, like Ghana (eligible with GNI per capita of $1,550) and Uzbekistan (ineligible with GNI per capita of $1,720).

Similarly, the Global Fund’s new allocation methodology scales the amount of money a country is eligible to receive by GNI per capita, effectively reducing the amount available to middle-incomes. There are provisions for a graduated reduction in “over-allocated” countries in the near-term.

But both policies merit a revisit given our renewed appreciation of the problems of country income classifications as a proxy for anything important.

If disease prevention and control is the goal of donors, then they should allocate where disease burden and coverage gaps are located and where their money can be spent most cost-effectively. And if crowding out domestic spending in health is the concern in middle-income countries, then donors need to create incentives in their own financing for public goods to counter free-riding.

As Sarah Dykstra points out in her blog: “if the new PPP numbers suggest anything it is that the quality of health or education or access to services associated with a given income has just gone down.” We’ll be watching to see how donors respond.

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.