Recommended

Blog Post

The European Commission has quietly announced that it now has major ambitions to recruit international workers for its green transition. This is sensible, necessary, and can be positive for all involved. It will, however, face challenges. This blog reviews the EU’s goals, and suggests ways to go about fulfilling them.

The EU’s green skills crunch

The EU’s green skills gap is “enormous” according to a European Parliament Policy Study. Labour shortages across sectors key to the green transition doubled from 2015 to 2021. The EU’s solar strategy has recognised that there are already skill gaps, and industry actors have warned of an “unprecedented skills shortage”: more than 500,000 additional workers will be needed by 2030. Spain’s solar industry is currently unable to take on more projects, despite government assistance, due to workforce shortages. In Germany, 60 percent of electrical contractors have vacancies, and a shortage of over 200,000 skilled workers has been identified. France will need at least 100,000 more workers by 2030 to meet building renovation targets. Swedish solar installation companies will need nearly 30,000 more workers over the next five years. Internal upskilling and reskilling will be important, but as will be seen below, this is already recognised to be insufficient.

Reviewing the development of EU green mobility thinking

Faced with these challenges, the EU’s thinking on green-skilled mobility has gone from absent to urgent. Its 2020 European Skills Agenda stressed the importance of the ‘green transformation’ and mentioned the importance of targeted migration pathways, but did not tie the two together. But only two years later, in April 2022, the Commission published a communication arguing migration is “an investment in the economy and the society as a whole, supporting the EU’s green and digital transition, while contributing to making European societies more cohesive and resilient.”

And in early 2023 the European Commission’s ‘Green Deal Industrial Plan for the Net-Zero Age’ recognises that skills are a key impediment to the EU’s green transition and that the union will “facilitate access of third country nationals to EU labour markets in priority sectors” through the creation of an EU Talent Pool, allowing the recognition of third-country nationals’ qualifications and matching with skill gaps.

A consultation on the EU Talent Pool is now active. The consultation’s briefing note recognises that “extensive shortages” of skills necessary for the green transition “are likely to continue acting as barriers to growth”,and that “labour migration must be part of [the] policy mix if the EU is to meet current and future labour market demands and respond to demographic trends.”

The EU’s goals

The EU faces an urgent green transition, a tight labour market, and an ageing population. Migration can contribute to addressing all three, but firms wanting to recruit workers often struggle to do so:

- Qualified third-country nationals outside the EU can lack adequate channels for accessing EU employers: it is difficult for third-country nationals to identify suitable opportunities and apply for a job before migration

- Firms lack the ability to assess the genuineness and comparability of foreign qualifications

- Policymakers don’t have a fully accurate vision of labour markets, and therefore face challenges in targeting labour visas to sectors and skills

The proposed EU Talent Pool would act as a resource for both potential migrants and employers in three key sectors: the digital sector, healthcare, and the green sector broadly speaking. It would:

- Collect profiles of candidates meeting individual criteria for the EU Blue Card (work and residence permit)

- Hold profiles of external job-seekers, with related documents and links to external qualification profiles

- Provide access to national contact points, which would mediate consultation and search of profiles

- Collate and advertise jobs vacancies to candidates applying to the pool

According to the Commission’s Green Deal Industrial Plan, this would complement the EU Skills Agenda’s aim of facilitating recognition of qualifications, allowing a ‘fast track’ for recognition and immigration of workers with needed skills.

Challenges in sourcing green-skilled workers

Migration is an area of shared EU-state competence, and the any expansion of migration programs will have to overcome this political challenge. But there are also practical issues with the talent pool. It is being developed under the assumption that ‘build it, and they will come’. The trouble here is that the issue is one of both demand and supply.

Other sectors are also facing worker shortages, and will be competing for the green-skilled workers available internally. The green sector hasn’t had a positive wage premium for several years. Workers with transferable skills areas are likely to be attracted to sectors where premiums remain—including the digital sector. They will also be sought by the fossil fuel industry. The 2023 Global Energy Talent Index, which surveys over 10,000 renewable energy industry workers, found that 78 percent of those workers were offered a new job last year. 87 percent said that they would consider leaving their new role; 51 percent were happy to move to the oil and gas sectors, and 59 percent citing pay differences as a key factor in decision-making. The fossil fuel sector is currently highly profitable and investing in new infrastructure. It, too, can offer a wage premium that green sectors currently cannot.

The EU is not alone in looking for green-skilled workers. Other Global North countries are competing for the same skills as well. The US, for example, currently has essentially no domestic offshore wind workforce; it expects to require over 80,000 offshore wind workers by 2030 to meet targets. It also needs at least a million more electricians over the next decade. In the UK, workforce constraints are “the biggest single threat to the UK’s huge offshore wind ambitions”, with the same problem reported in numerous other sectors.

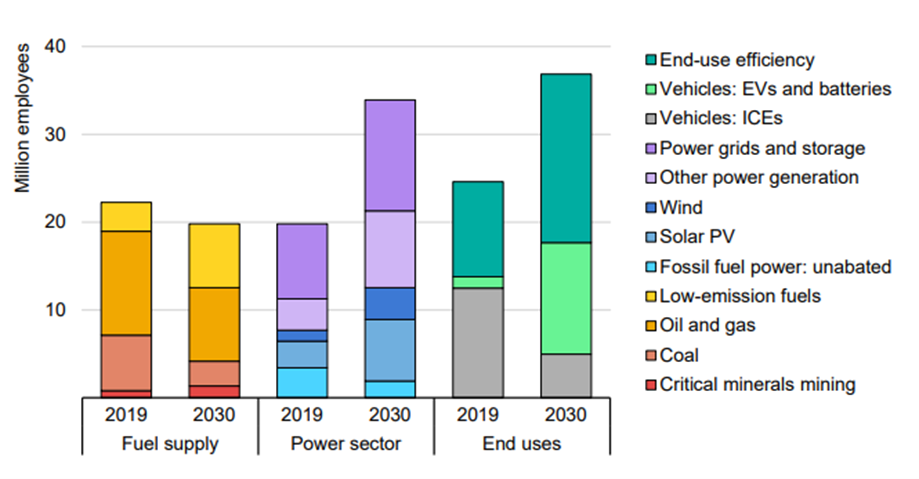

If there is considerable alternate demand for workers, even more serious is the absolute shortage workers with the desired skills. The International Energy Agency estimates employment in green sectors worldwide needs to increase from 33 to 70 million between 2021 and 2030 to achieve climate goals.

Global energy sector employment by technology in the Net Zero Emissions by 2050 Scenario

Source: IEA, 2023.

How to go about it

Because there is no reservoir of green-skilled workers with few prospects outside the EU, the Talent Pool is not enough to deliver the tens of thousands of workers needed. To the extent it does succeed, it risks creating a harmful drain of green-skilled workers out of sending countries, slowing green transitions elsewhere.

The EU should pair training with migration, an idea alluded to in the Talent Pool briefing note.

The first step in such a process is to identify the sectors requiring skilled workers, and the skills needed. In some areas this has already been undertaken; in others more work is required.

The second step is to assess whether countries exist where there are surpluses of workers in those areas. This is unlikely to be widespread, but may be the case in some sectors. India’s Skill Council for Green Jobs has been effective in training green-skilled workers, for example. It may have trained an excess of solar workers from 2019-20 (although a solar industry recovering from COVID-19 and buoyed by recent government investments may already have created sufficient demand to employ these jobseekers).

The third step is to assess which countries could feasibly be partners in a green-skilled training and migration partnership. Consideration should be given to:

- Existing training capacity

- Whether the partner country’s green skill needs are expected to be similar to that of the destination country

- Whether partner country training standards and qualifications are close to those of the destination country

- The GDP of the partner country, and the relative impact of remittances upon development there

- The partner country’s demographics, and the need to create jobs for unemployed young people

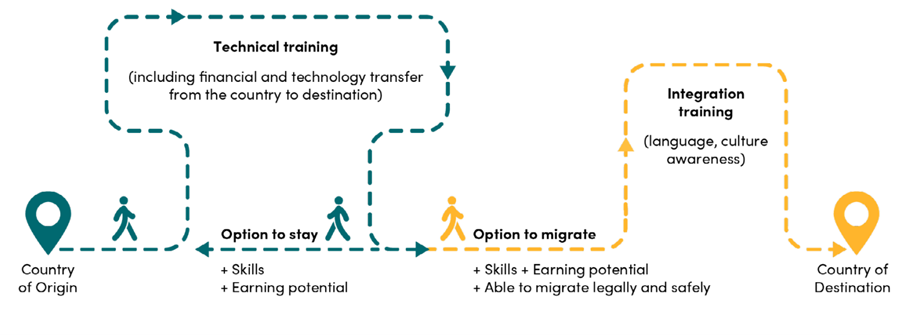

This approach matches the Global Skill Partnership model. In this model workers are trained to necessary standards in the country of origin. Part of the cohort then moves to work in the country of destination, while part stays to work in the country of origin. The migrant cohort works for a pre-determined amount of time in the country of destination, before returning. This provides a triple win: destination countries with needed workers; migrants with skills, money, and knowledge; and the country of origin with remittances and subsidised training of necessary skilled workers. In the case of a green skills partnership, this is elevated to a quadruple win: the climate is a global public good, and training more workers to fill skill gaps benefits everyone, everywhere.

The Global Skill Partnership model

Source: Dempster et al., 2022.

The potential for circular migration within the Global Skill Partnership could be particularly attractive in a sector seeing dramatically falling costs (solar module prices have dropped 99.6 percent since 1976, for example). This means green investments become increasingly attractive over time, and more cost-competitive in lower-income countries. A worker from a sending country would be trained at the expense of the destination country; they would move, earn money, gain skills, and reduce subsequent global adaptation needs by aiding mitigation in the destination country; and then could then return to establish or join a green business in a sector now booming due to reduced technology prices. Providing developing countries with a pipeline of green-skilled workers now would have limited impact: as in India’s experience of solar workers, they will move to other sectors if the capital is not there. Providing them with a reliable pipeline of trained, experienced workers arriving in six or so years, when capital will go further in buying green tech, could be better.

For both development and adaptation, an increased supply of clean energy is crucial. 13 percent of the world’s population currently does not have access to electricity. Access to power is vital to high-productivity firms and can help create hundreds of millions of jobs. In healthcare, distributed renewable energy can provide clinics with light and allow refrigeration for vaccination cold chains. In fragile states which struggle to maintain energy grids, distributed solar can be transformational. Increasing the energy skills base in developing countries is a critical part of the global infrastructure challenge.

Next steps

The European Commission and Member States will need to move fast, but carefully, to avoid missteps and harm to partner countries. Next steps should include:

- Mapping internal green trajectories and skill needs

- Assessing domestic reskilling capacity in different areas

- Mapping external green trajectories and skill-building pipelines. This could involve a drive to establish green skill mapping at the global level

- Analysing existing qualification overlaps between EU Member States and third countries.

- Improving qualification recognition processes for migrants

- Analysing the costs and capacities of training pipelines in third countries to establish where they could be scaled most efficiently as part of a Talent Partnership

- Analysing the development, mitigation, and adaptation impacts of Talent Partnerships with possible partners

- Conducting pilots where efficient and feasible, in preparation for scaling up migration to support EU green sectors

- Preparing to provide capital support to green sectors in countries of origin, to support members of trained cohorts remaining in situ, and to grow sectors elsewhere in preparation for the return of circular migrants

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Adobe Stock