Recommended

Finding coherency in the EU’s migration approach has always been hard. Demographic pressures and labour shortages highlight the need to rethink the restrictive migration policy, while voters preferences and tensions within the bloc on how to deal with irregular migrants highlight how contentious the issue is. Further, among twenty-seven Member States, the goals of some will always be at odds with those of others. Following February’s European Council summit, progress seems harder than ever. There are however still some bright spots. We suggest learning from recent moves made by Germany and Spain, and approaching migration in a more holistic way.

Migration at the 2023 EU summit

Migration received little public and media attention in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the highly contentious issue is back in the spotlight. With the number of illegal border crossings reaching the levels of 2016 and continued issues between Italy and its neighbours relating to NGO-run ships saving migrants in the Mediterranean, migration is back on the agenda. It was therefore not anticipated that the EU leaders’ summit in February would be an easy set of meetings. In anticipatory debates in the European Parliament, MEPs as expected revealed conflicting views. Priorities differed: bolstered borders; faster returns; work on the ‘root causes’ of migration; clampdowns on Mediterranean rescue operations; and, only occasionally, increased legal migration pathways.

The Swedish EU Presidency, presiding for six months, is resistant to migration, reflecting domestic tensions and the new government’s approach more generally. Recent gains by right-wing parties elsewhere have thrust migration further into the spotlight, making progress on a more coherent EU-wide approach harder. In a letter ahead of the meetings, eight countries called for swifter return of rejected asylum seekers and strengthening of the border. At the European Council sessions, leaders ultimately agreed in late-night meetings to focus on strengthening border defence, de facto paying for increased walls, and on accelerated returns.

Competing demands: the reality of a declining workforce vs calls for a restrictive migration policy

In the European Commission’s 2023 communication on migration and asylum, “an ambitious and sustainable EU legal migration policy” was described as “an important component in successful partnerships”, and “urgent [given EU] skills gaps”, highlighting the need for the EU to attract workers from outside the bloc given the demographic outlook on the continent with its declining workforce. In the final statement following the European Council summit, by contrast, migration partnerships with countries of origin and transit—long a key element of EU migration policy—were not mentioned at all. Migration was described as “a European challenge that requires a European response”. The European response, summarised by the headings of the statement, will include:

- Increased external action, seeking to “prevent irregular departures” from other states through border strengthening elsewhere and action to reduce the ‘root causes’ of migration

- Enhanced cooperation on returns and readmissions, using tools like visa restrictions to encourage third countries to accept rejected asylum seekers

- Control of EU external borders, including “affirm[ing] full support for… Frontex”, the EU’s border agency accused of serious human rights violations in a 123-page report

The New Pact on Migration and Asylum, the EU Commission’s 2020 flagship initiative proposed to build a more coherent migration policy across the bloc is relegated to a small paragraph, with its primary focus remaining that of returns.

This is a pity. The EU Talent Partnerships have a lot of potential. They rely, however, on trust between stakeholders brought together to coordinate something that is mutually acceptable. The EU’s approach to labour mobility is, however, not currently one to inspire trust in third countries. In a leaked Commission document on external migration engagement, migration partnerships are presented as essentially a reward for returns. Countries are eligible if they first agree to pre-requisites on returns and externalisation. To give more respect to partners, and have a greater chance of successful outcomes, it may be better to discuss returns and migration partnerships simultaneously, rather than waiting for a pre-condition to be fulfilled before opening conversations. This may—as discussed below—be where Germany’s new migration approach can hold lessons.

The European Council’s approach is not all-important. More positive activity can continue below the radar and at the Member State level. As an overall policy direction, however, it poses problems in two ways. Firstly, as pointed out, it fails to recognise that the EU has enormous need of third-country workers. Secondly, it strips the EU of one of the greatest tools for development to which it has access.

Workforce constraints

The EU faces a declining workforce. Eurostat estimates that the percentage of population in the working age bracket in the EU will fall from 65 percent in 2019 to 55 percent in 2070. Charles Kenny and George Yang at the CGD have put a figure to that, arguing that there will be 95 million fewer working-age people in Europe in 2050 than in 2015.

These workforce shortages are especially evident in two sectors: care, and green skills. An ageing population requires more care workers, but has a smaller pool upon which to draw. Migrant care workers from countries experiencing demographic booms, such as Nigeria, can help meet these needs.

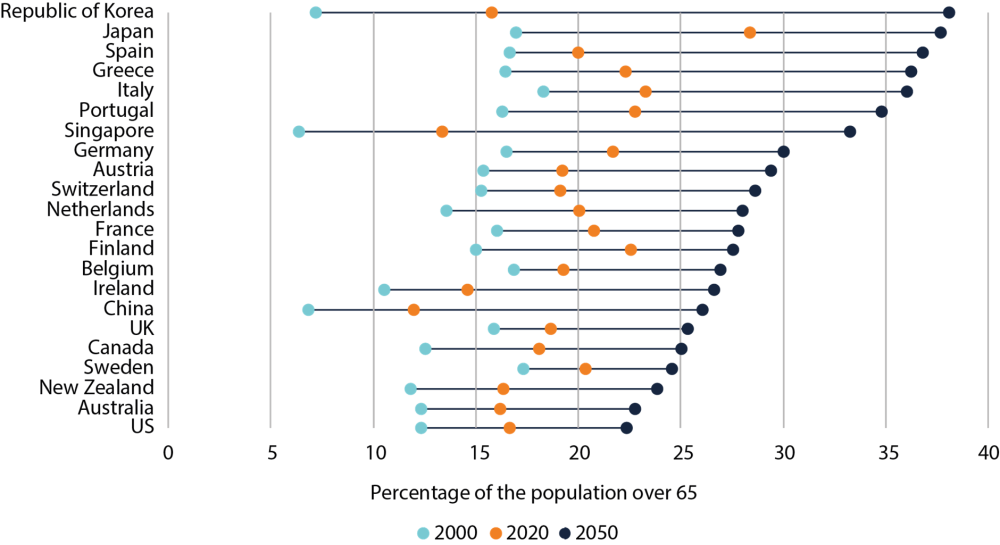

Ageing trends in selected countries, 2000-2050

Source: Kumar et al., 2022.

In green sectors such as building retrofitting and solar panel installation, the EU faces a tight timeline to meet its net zero targets by 2050, and a major shortage of workers. The green transition has barely begun, but European solar photovoltaic firms are already warning of major skills bottlenecks. Much of this can be addressed domestically. The European Pact for Skills, launched in 2021, aims to reskill over 6 million people. This will however not be enough, and migration will be necessary as a complement to domestic reskilling and upskilling. The EU Commission has recognised this in its 2023 Green Deal Industrial Plan, which calls for the facilitation of labour mobility from third countries. A new EU call for evidence also recognises that “given the urgency and the magnitude of the challenge, labour migration must be part of [the] policy mix if the EU is to meet current and future labour market demands and respond to demographic trends." These pathways should be carefully considered. They will need to be equitable and to avoid draining the skill pool of countries of origin, to avoid harming green transitions elsewhere.

The development potential of migration

Migration programmes are one of the highest-impact tools countries have for facilitating development. For many countries, especially small states with few options for development, access to migration is possibly the most effective way of increasing economic development through remittances and skills accumulation. A programme mounted by the US to assist reconstruction in Haiti following the 2010 earthquake, for example, allowed Haitians to undertake agricultural work in the US for two to three months in 2015-16. On average, this short stint by a single migrant doubled the annual household income. These gains are larger than any other poverty-reduction policy.

This kind of programme could play a major role in helping climate-vulnerable communities to adapt in situ, providing transformative remittances while meeting EU labour needs in sectors with a shortage of domestic workers. Some Member States have realised that a more holistic approach to migration is needed, to their own benefit.

Germany is leading the way

The European Council may have homed in on border securitisation, but some Member states are accepting the need for increased labour migration. Germanyn in February appointed the first ever Special Commissioner for Migration Agreements. The job of the Special Commissioner will be to “draw up practical cooperation agreements with key countries of origin”, considering enhanced economic cooperation with partner countries; training programmes for the German labour market; qualification smoothing; and, last but not least, the return of asylum seekers whose claims are rejected. Importantly, legal migration and returns are to be discussed simultaneously, with deals agreed that suit both sending and receiving country. Joachim Stamp, the new Special Commissioner, suggests that this comprehensive approach is an alternative to “barbed wire”.

Germany’s approach complements its new Skilled Immigration Act, intended to make it easier for skilled workers to come to Germany and easier to regularise irregular migrants.

The Special Commissioner will coordinate closely with federal ministries, but will have the authority to advise on migration and negotiate partnerships. This is a promising approach, but is not complete. To fulfil domestic needs while also maximising the development impact of migration, Germany should expand the mandate and capacities of its Expert Council on Integration and Migration, allowing it to conduct research into partner countries that would most benefit. This would allow labour migration policy coherent with development.

This new approach is putting up some positive green shoots already. In Ghana, Germany previously supported a centre originally intended to advise potential migrants against mobility and to assist returned migrants in reintegration. Instead, the centre will be used to inform Ghanaian workers of labour mobility options to Germany and the EU more widely. Germany’s Development Minister described this as “turn[ing] a one-way street into a two-way street… for our mutual benefit”, recognising that Ghana needs to find jobs for its young people, and Germany needs workers.

However, one has to note that even if seen through and implemented, Germany’s holistic migration policy will not be able to resolve some of the underlying issues at play in Europe. Due to the shared borders and a common system to manage visa and asylum applications (Schengen/Dublin), a truly comprehensive and holistic approach can only be applied if implemented by all EU Member States.

Spain setting a similar course

Spain, like Germany, is moving to confront shortages in key sectors, exacerbated by its ageing population. The average truck driver in Spain is now fifty years old, and Spain already faces a shortage of 10,000 to 20,000 drivers. Europe more widely faces a shortage of 400,000 truck drivers. In the face of this, Spain is preparing a pilot programme bringing workers from Morocco to bolster the sector (the number of truck drivers has not yet been set). It is also implementing and preparing new temporary work visa programmes with countries in Central and South America. In August 2022 Spain passed a law allowing irregular migrants to become regularised if they have lived in Spain for two years and agree to be trained to fill positions of shortage. Training irregular migrants to match skill shortages may be easier and cheaper than long deportation proceedings.

France following likewise

France in late 2022 announced that it too would seek to approach labour migration with “pragmatism and realism”. Like Spain, it aims to regularise those who are already in the country, and to guide them towards sectors stretched for workers. This is intended to help to avoid increased immigration. The new bill was presented to ministers on February 1, 2023. It envisages providing a one-year regular residence permit to those who have already been in France for at least eight years, and who have spent at least eight months working in a shortage sector in the previous two years. Asylum seekers considered more likely to have their application granted (seemingly assessed according to the rate at which protection is afforded), furthermore, will be able to work immediately. At the same time, the bill also reduces the protections against deportation of those who commit a crime with a punishment of ten or more years of imprisonment.

Next steps

The European Council’s conclusions are not unexpected. Encouragingly, Member State activities do not fully match the Council’s priorities, and there are good practices to be shared. Moving forward, we emphasise that the EU and Member States should:

- Respect the principle of non-refoulement in returns

- Be upfront about the need for labour migration to address demographic trends and meet workforce constraints

- Respect partner countries’ and migrants’ needs in migration agreements. This could see a greater emphasis on Talent Partnerships in areas of shared skill needs

- Prioritise partner countries according to the development impacts of migration partnerships

- Consider following Germany’s use of a Special Commissioner, to allow migration policy that is better joined up across policy areas

- Discuss returns and regular pathways simultaneously

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Adobe Stock