Recommended

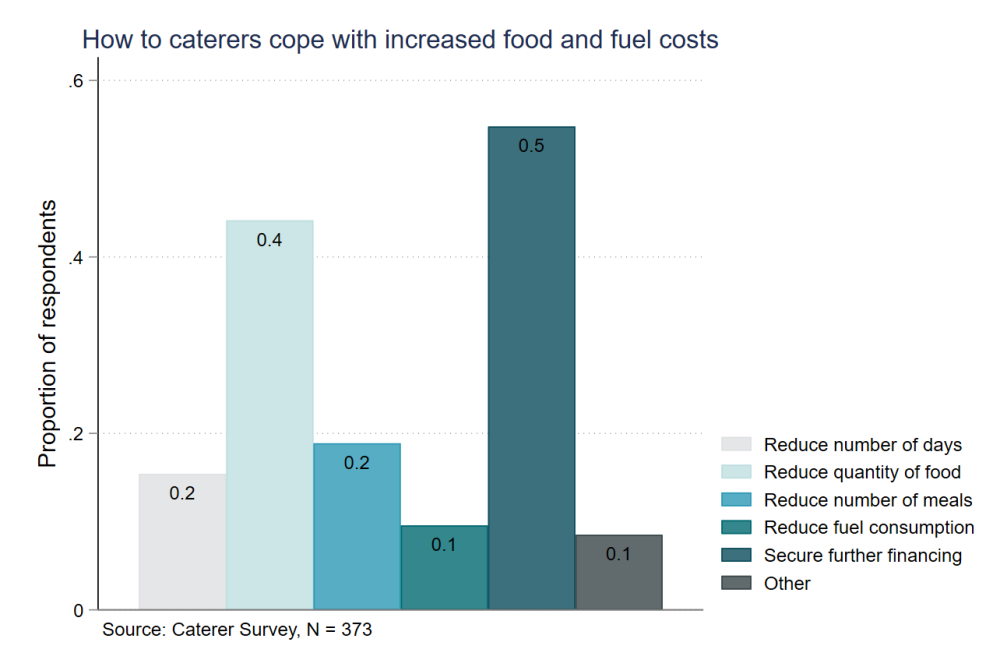

School feeding programmes have grown in popularity in many low- and middle-income countries, including Ghana, over the past decade. However, recent developments in global and domestic economic environments have exposed key vulnerabilities in sustaining such programmes. Previously, we described the current challenges and opportunities for financing of the Ghana School Feeding Programme (GSFP) and made the case that evidence is key to ensuring the sustainability of its operations.

Our forthcoming study provides insights into the performance and long-term sustainability of the sector, particularly which strategies are being used in the face of a prevailing turbulent economic environment. The survey covered 376 caterers, 338 school headteachers, 1,425 parents and over 5,094 students across 15 districts in Ghana. We also spoke with district level School Health Education Programme (SHEP) coordinators from over 200 districts to collect additional data on monitoring and accountability and system level support provided to caterers for implementing school meals.

Everyone agrees that Ghana's school feeding programme is an important and useful social programme…

Ghana’s SFP has been operational since 2005 and currently serves over 2.6 million children across 9,000 pre-tertiary institutions. It provides an essential social safety net for the poor, disadvantaged and vulnerable population, and has steadily been advancing towards universal coverage. As of the 2022 budget, the programme covered nearly 85 percent of all public schools in the country.

Schools are selected for GSFP inclusion based on a combination of geographical, educational and socio-economic factors, such as school enrolment rate—especially for girls—and level of hunger, food insecurity and poverty in the community. The school level analysis reveals that the GSFP is largely targeted at areas experiencing high levels of poverty. When we asked headteachers why their school had been selected for the school feeding programme, their responses mirrored the guidelines—high rates of poverty in surrounding areas (66 percent), followed by low enrolment rates (49 percent), were the most commonly cited reasons for school selection or rather inclusion on the GSFP.

The primary implementation agents for the programme are private caterers, who are awarded contracts to procure, prepare and provide food for students in selected schools. Our survey with caterers revealed three types of recruitment pathways - while almost 44 percent were selected via an application or tender, 43 percent were appointed through political connections, and 9.5 percent were selected based on a recommendation by a relative or friend.

Our data shows that the GSFP is well-targeted and the main beneficiaries of the programme—parents and children—ascribe high value to it. Specifically,

-

Nearly 50 percent of students surveyed say they will go hungry without school meals.

-

Over three-quarters of headteachers believe that school meals will continue to be offered in their schools next year, suggesting that the needs of the community will continue to warrant the programme’s provision.

-

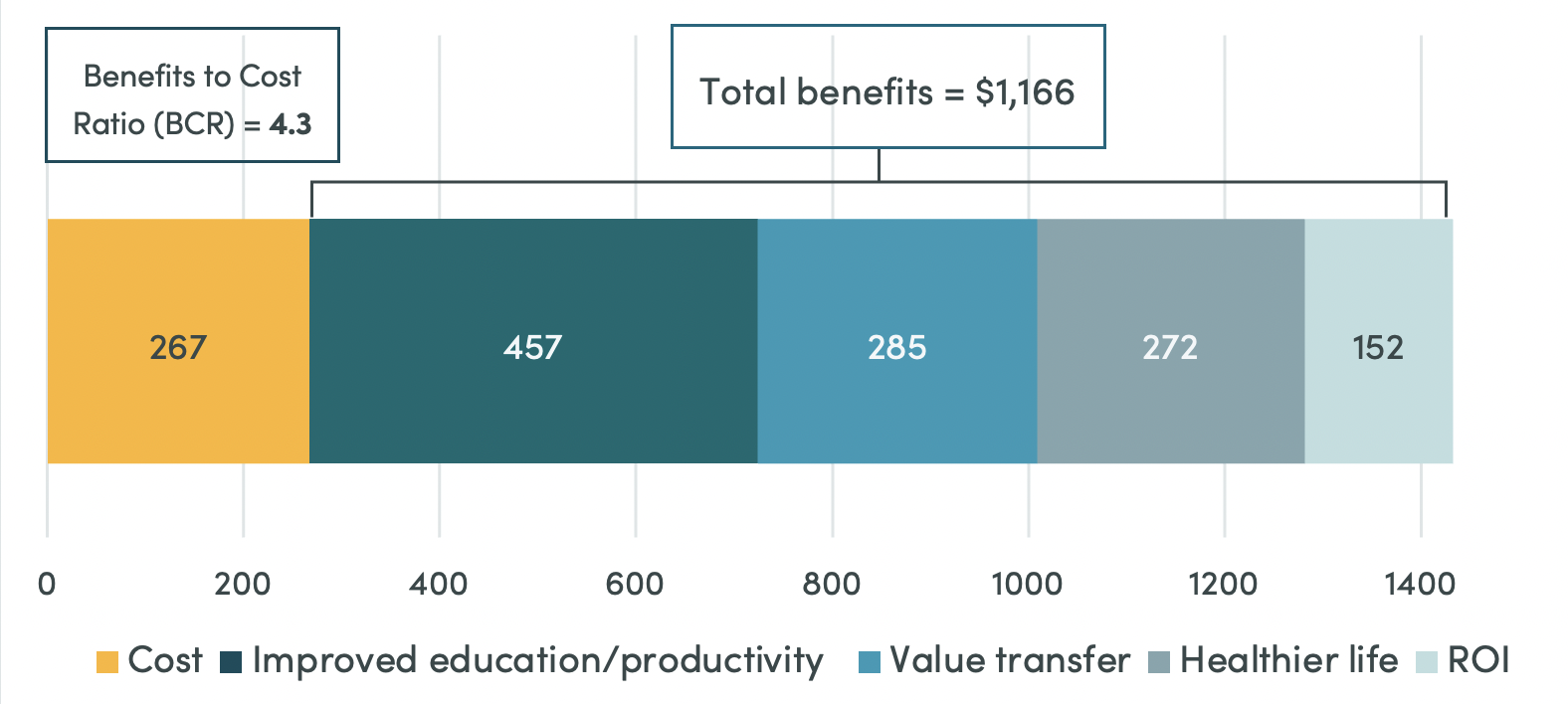

Nearly 90 percent of household heads think the GSFP is a useful social program. Most (nearly 80 percent) prefer on-sight meals rather than cash or take-home rations (see Figure 1)

Figure 1: Parents’ preference for school meals over take-home rations or cash

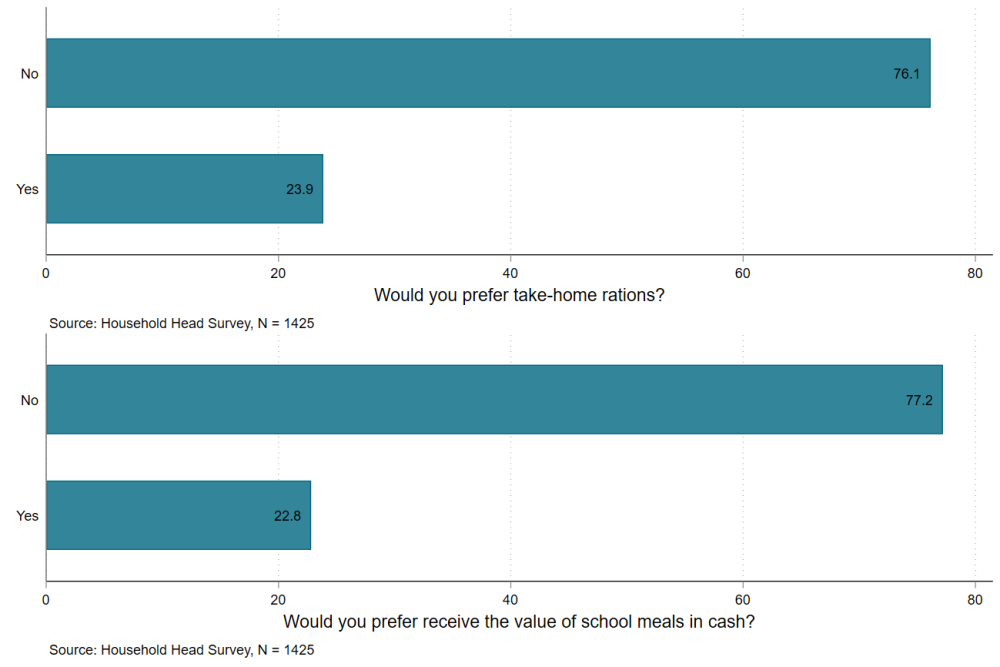

… but insufficient and poor quality food is compromising its impacts

According to our survey, more than a quarter of headteachers (28 percent) and over a third of household heads (37 percent) believe the school meals do not meet proper nutritional expectations or are only marginally nutritious. But the issue of the nutritional value of school meals might have to wait in line for now, because the more fundamental and important issue reported by all stakeholders is that there is not enough food to start with. More than 60 percent of headteachers and household heads said food served to children is less than sufficient (see Figure 2). In fact, 44 percent of the surveyed children reported that the reason they were not served a meal on some school days was because “food was finished”. More than 30 percent of children want to increase food quantity when asked what they want to change about meals provided.

Figure 2: Headteachers’ and household heads’ perceptions of quantity of school meals served

The Ghana National School Feeding policy only dictates the per meal allocation granted to caterers, which has recently increased from 0.97 Ghana Cedi to 1.2 Ghana Cedi (or around 0.1 USD) per meal. Within this per-meal allocation, menus are set by the School Feeding Secretariat at the district level to provide at least 30 percent of daily nutritional requirements to kids in the form of one hot meal. While nearly 80 percent of caterers say they follow the menu provided by the school feeding secretariat multiple days per week/everyday in a typical week, 40 percent of headteachers say caterers deviate from the menu multiple days per week/everyday.

Government financing remains a challenge

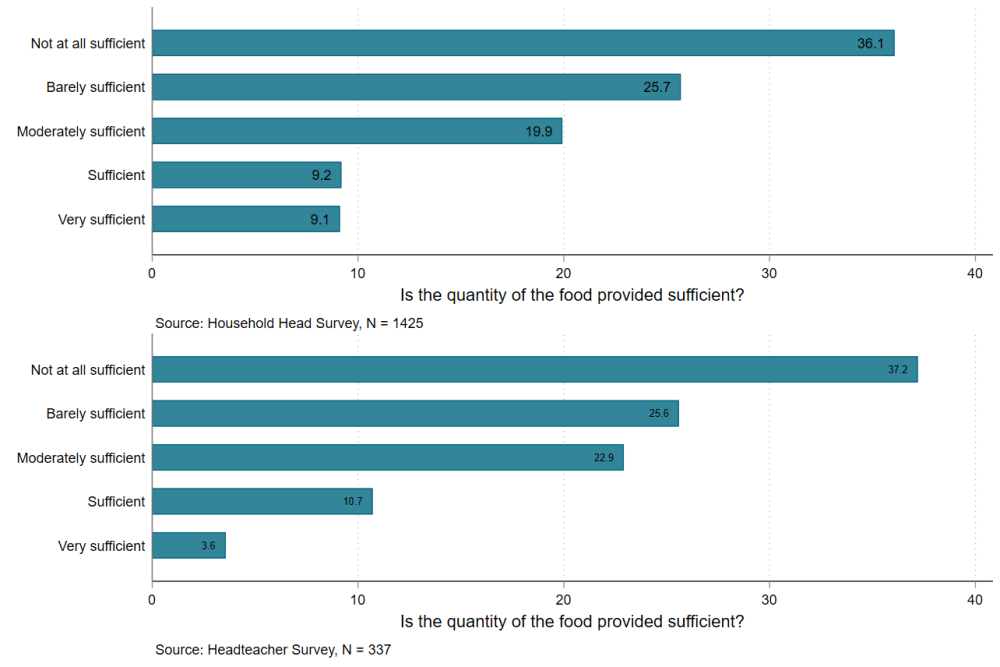

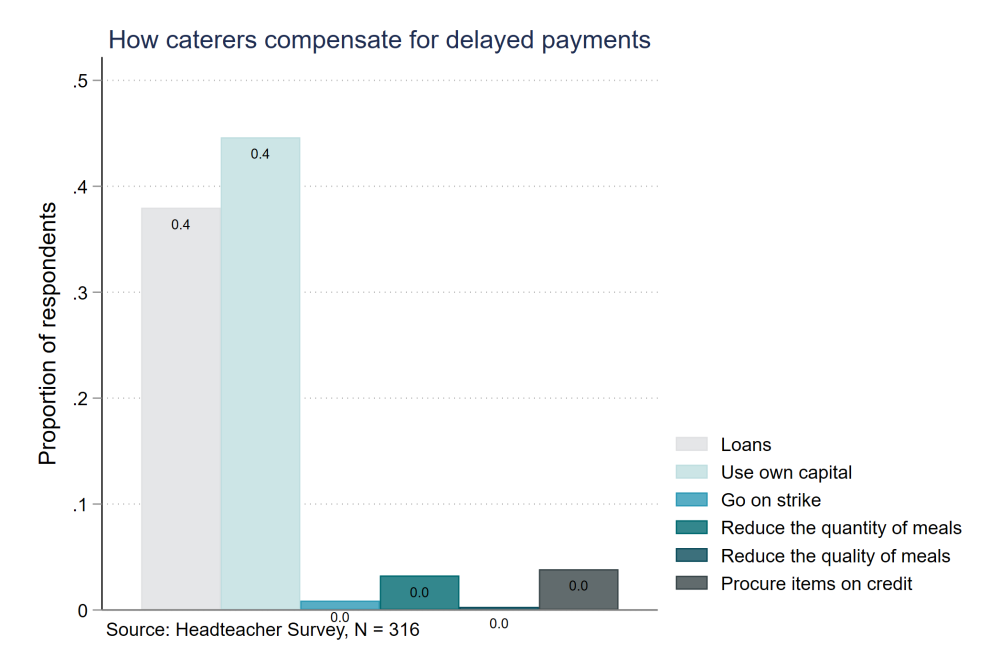

What are the reasons for insufficient food and menu deviation? 40 percent of caterers in our survey say in coping with rising prices, they cut down food quantity (see Figure 3). More than 45 percent of headteachers report that caterers rely on their own funds to cope with delayed payments. This implies that caterers may have to draw on proceeds from their other businesses to manage cash flow problems in their school feeding operations, given that a large majority of the caterers (70 percent) also operate another small business.

Figure 3: Coping strategies adopted by caterers, given increasing costs and delayed payments

Financial constraints are the focus of the ongoing policy debate around school meals in Ghana. There are recurring strikes by caterers to protest chronic arrears and inadequate grant funding. But issues with late payments existed even as far back as 7 years ago, and were already linked to the failure of the program to enable caterers to procure produce from local smallholders. Previous studies revealed that caterers face significant challenges primarily related to fluctuations in food prices and lack of control or agency due to delayed payments.

Our data shows that there’s a high proportion of caterers (more than 30 percent) that did not receive any payment in the past year. Irregular and delayed payments are part of the reason caterers have to engage in credit purchases. Caterers in our survey state that as much as 75 percent of the food items purchased are on credit from traders. For the plurality of caterers, the repayment period for these food items is irregular (41 percent). As a condition for supplier credit, caterers had to agree to repay at prices that are above market prices (41 percent) or commit to buying further foodstuff only from the same vendor (10.7 percent), whether the prices are competitive or not. The only basis for this agreement is the supplier's willingness to sell on credit. This indicates that the lack of suitable short-term financing facilities could ultimately undermine the quality and quantity of school meals by exposing caterers to high transaction costs.

Neither carrot nor stick: the GSFP lacks broader support packages and requires robust accountability mechanisms

The caterer-based model of school meals provision that Ghana has adopted is supposed to free up government agencies and schools from the day-to-day affairs of preparing and delivering meals by outsourcing the service to the private sector. This could also reduce the cost of school meals by harnessing the efficiency of private sector operators. Outsourcing the service to small and micro enterprises mostly operated by women could also have added economic and social empowerment benefits. However, the functioning of such a system depends on the availability and efficiency of ancillary services which might be lacking due to various market failures and structural problems. As such, the government's role in facilitating the provision of such services could be critical to the success of the school feeding programme.

It appears that there is currently little support from the government, aside from the payment of the feeding grant which is considered both inadequate and irregular. Over 95 percent of SHEP coordinators reported that the district provides no support in facilitating access to financing, despite the fact that 80 percent of caterers identified finance or cash flow as the most significant constraint. Similarly, only 8 percent of SHEP coordinators claimed that the local government offers support/advice to caterers on procurement—typically good initiative but essentially insignificant.

Nearly half of the headteachers and caterers report in-person monitoring is most likely to happen only once every term. A significant proportion of SHEP coordinators (more than 40 percent) seem to lack any knowledge of this, and say they do not know of any monitoring mechanism or the question does not apply to SHEP. More than 50 percent say they do not know how caterers are held accountable for their service delivery. 15 percent of SHEP respondents say there is no monitoring for GSFP. These findings are disconcerting, given the central role of SHEP in the GSFP and its overarching vision to “create a well-informed and healthy school population”. Parents seem to be almost entirely absent from this process, cited by less than 5 percent of caterers as the responsible party for monitoring.

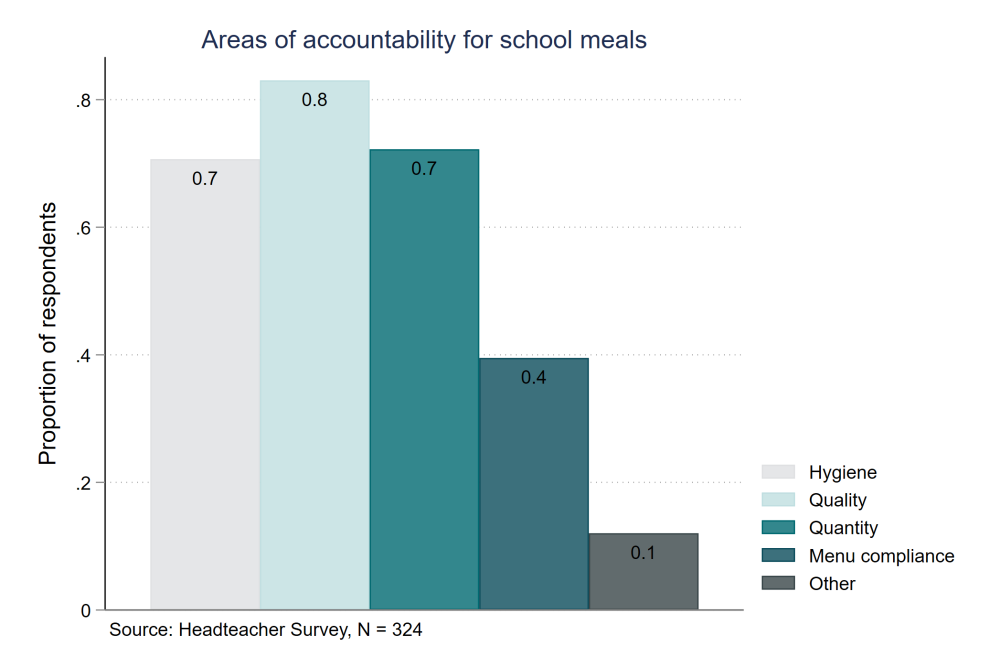

Despite concerns regarding the reliability of the system, the survey findings reveal (see Figure 4) that existing monitoring primarily focuses on the quality of meals served to the pupils. Aside from the quality of meals, there is emphasis also on the hygienic conditions of the meals as well as the quantity of meals served. There is a relatively low number of schools monitoring menu compliance, though this is, in theory, a key element of the programme.

Figure 4: Areas of accountability for school meals, as reported by headteachers

Improvements are essential to achieve the GSFP’s goals

Overall, the study shows that the GSFP continues to play a crucial role as a tool for preventing hunger in schools despite significant macro-fiscal headwinds. But survey data suggest the GSFP lacks adequate support from the government, as well as a robust monitoring and accountability mechanism. The inability of the government to hold up its end of the bargain by financing the programme adequately and on a timely basis might have denied it the leverage required to enforce accountability. Apart from increasing funding for the programme to the extent that the fiscal space allows, ironing out inefficiencies and potential inequities could make the programme more resilient. Although headteachers confirmed that appropriate criteria were used in selecting schools, further evidence is needed to ascertain the extent of inclusion and exclusion errors in targeting. It is also crucial to improve the operating ecosystem with private sector development initiatives targeted at relevant service providers across the school feeding value chain. The programme has huge potential for positive impacts for Ghana’s poor households, but without these necessary changes, its future is uncertain.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Christian Aid Images / Flickr