Recommended

Over the past year, two trends have posed a challenge to the post-pandemic recovery of many low- and middle-income economies: growing imbalances in public finances on the one hand, and increasing exposure to global food price shocks of vulnerable households on the other. What makes the situation considerably tricky for many developing countries is that the tools they need to deal with the second challenge are becoming increasingly out of reach because of the first.

In the education sector, one of the most effective measures for protecting vulnerable children in times of crisis is school meals. But the provision of school meals is threatened by macroeconomic imbalances in many countries at the very time it is most sorely needed.

As more countries approach the International Monetary Fund for a bailout, the fate of critical school feeding programs hang in the balance.

Ghana’s conundrum

Ghana has shown a commitment to expanding the provision of school meals over the past decade. The Ghana School Feeding Programme (GSFP) was launched in 2015, and has since grown to include schools across all 216 districts in the country. The programme is targeted at the school level, and presently 38 percent of primary school children are entitled to free meals at school. The government finances the GSFP fully out of the national budget. However, the often-turbulent budgetary situation in Ghana has lately deteriorated significantly, forcing President Akufo-Addo to pronounce it a “crisis”. This situation has led Ghana to seek help from the IMF, and will inevitably require the government to look into the composition and efficiency of public spending. Although this could help the country to get its fiscal house in order, care must be taken not to throw the baby with the bath water in the case of embattled social programs such as school feeding. Ghana’s handling of the current challenges may also set a precedent for the approach other low- and middle-income countries that are in a similar position could take in the near future.

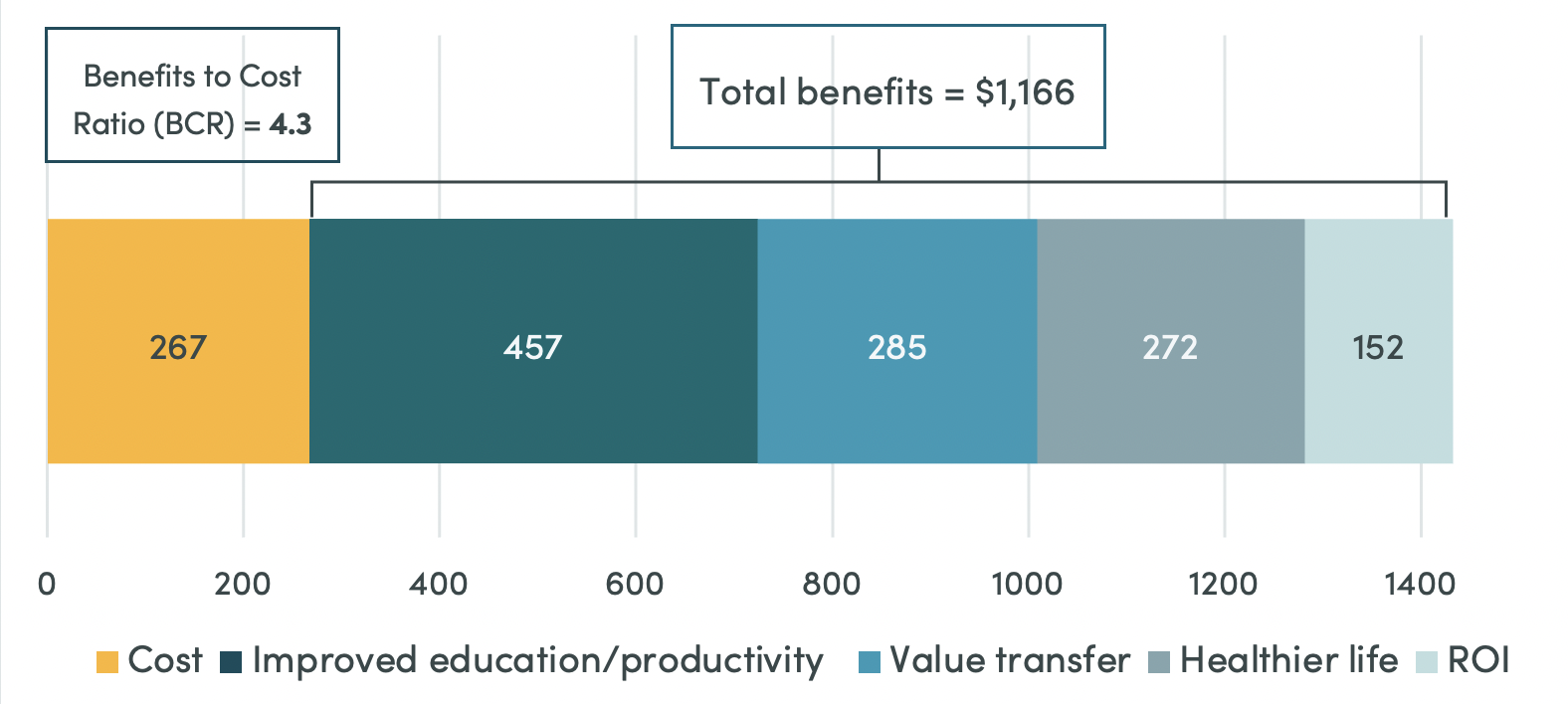

The benefits of school feeding for children and adolescents are proven, and range from positive health outcomes (alleviating hunger, reducing micronutrient deficiency and anemia, preventing obesity), as well as educational outcomes (improving school enrolment and attendance, improving cognition and academic performance, and reducing barriers to education access along gender and income lines). In Ghana, there is compelling evidence that school feeding improves learning outcomes particularly among girls and disadvantaged children. School meals are also cost effective with a total return of $4.3 per a dollar of investment, with benefits including returns to lifetime productivity improvements due to greater school attendance and learning, reduced public and private health expenditures due to nutrition and health benefits, monetary value of food transferred, spillovers from better participation of women in education and the economy, and returns on investment on freed-up funds.

Figure 1: Cost–benefit analysis of school feeding programs: average value per beneficiary for Ghana’s school feeding programme (in US dollars)

Source: WFP

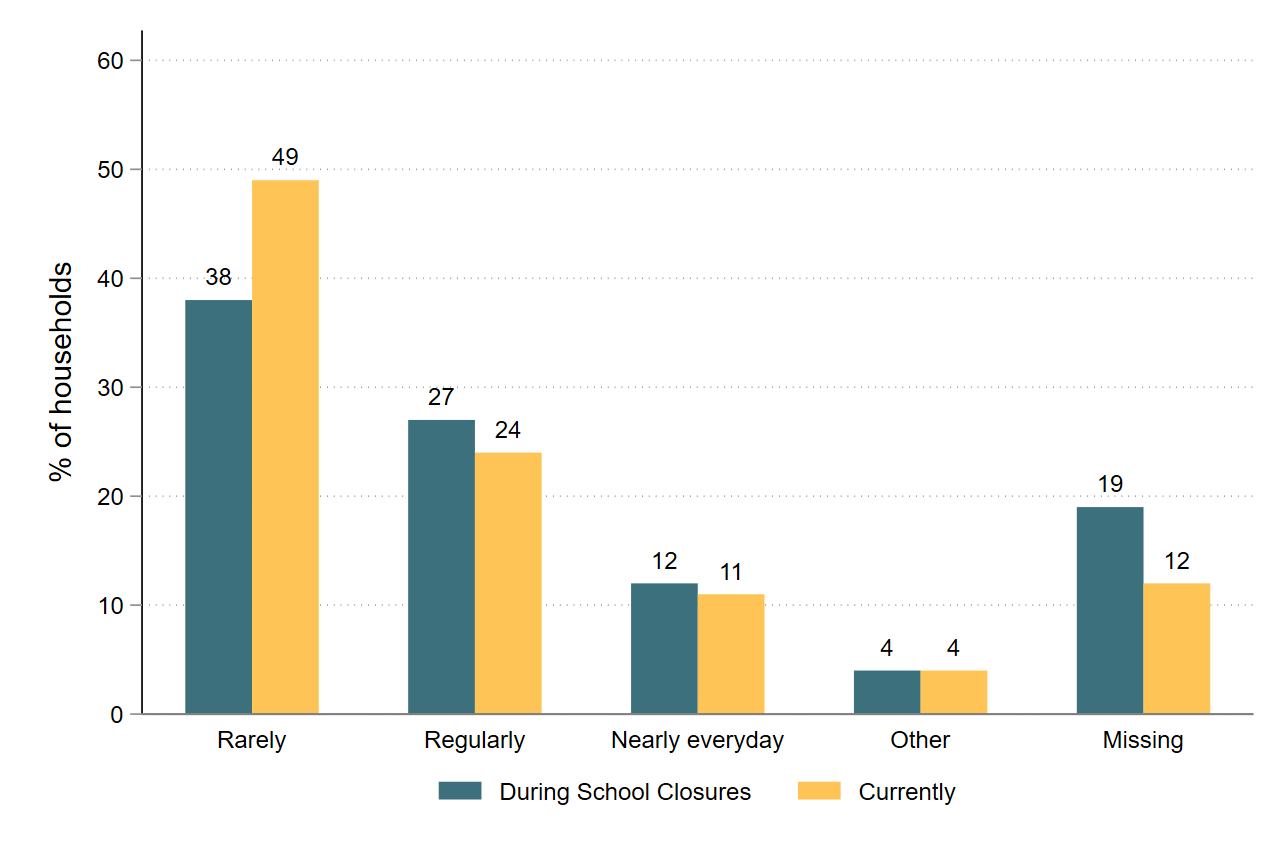

In our latest data, collected as part of a three-phased study that surveys a nationally representative sample of schools and households in Ghana, we found that provision of school meals is a determinant of school choice for the poorest households. Schools in urban areas and public schools are more likely to be offering free meals. Most schools suspended the provision of school meals during the pandemic because of school closures and associated social distancing measures. This meant that some children ate fewer meals per day—around 27 percent of students were regularly eating fewer meals during school closures (compared to around 24 percent children now). The still high proportion of kids eating fewer meals after schools reopened can potentially be linked to the high cost of food in recent months. These findings are indicative of the gap that can be filled by well-targeted school meals.

Figure 2: Frequency of children eating fewer meals than usual during COVID-19 related school closures

Source: CGD PREPARE Round 2 data

Regardless of the effectiveness of the program and the role it might be playing to protect the education of vulnerable children, school feeding has come under enormous financial pressure due to the overall macroeconomic imbalances Ghana is experiencing. Earlier this year, caterers and cooks were striking over unpaid fees, and there was an announcement that a planned expansion of the programme in 2022 had been suspended.. There are calls to increase the per-meal allocation from the current GH₵ 1 (0.073 USD) by 50 percent, amidst reports of poor quality and nutritional content of meals currently being provided to children. There is also increasing pressure to scrutinize the GSFP and the Free Senior High School policy, as two of the largest social sector programs that take up a sizable slice of the national budget.

We can see from media coverage in recent months that the GSFP is a popular and politically important program. So, while drastic cuts might not happen immediately, the program risks de-facto retrenchment due to per capita allocations falling short, and low-quality meals causing some pupils to refuse to eat the meals, leading to higher wastage and lower efficiency for the program. This might in turn damage the reputation of the program in the long run, eroding political support and further reducing the amount of resources available for school feeding.

In this light, the ongoing talks with the IMF could present an opportunity for reform, depending on how carefully the school feeding program is considered.

The ongoing IMF talks could influence the future of school meals in Ghana

First of all, any conversation on school meals should take into account the complex, multisectoral nature of the potential benefits of school feeding. There is often a tendency to try and force a sector-based straightjacket on school feeding which, in reality, has multifaceted benefits accruing to the education, health, social protection and local development sectors. Therefore, the argument for prioritizing school meals as a social investment should not be framed from an education or social protection standpoint alone.This also means that all relevant stakeholders should have a seat at the table where school feeding spending is considered.

Second, it is in the interest of children who might benefit the most from school meals to acknowledge that some difficult choices may have to be made. The status quo might not be sustainable, particularly if quality and consistency of school meals are taken into account. The most important step that can be taken to preserve the gains from school meals at this point is to put it on a more sustainable growth path. In this regard, the IMF talks could provide an opportunity to ask important questions contributing to the sustainability of the program. This might be a good time to look into issues of operational efficiency, choice of modality and targeting.

Third, at the same time as improvements in efficiency are being considered, innovative and additional financing should be given attention. It might be useful to consider the feasibility of flexible and differentiated mixes of financing options tailored to various circumstances. It is also imperative to revisit the role of the private sector and civil society organizations in running the program around the country.

Evidence is key for ensuring the sustainability of school meals

Ultimately, improving the efficiency and sustainability of the GSFP will require a nimble and evidence-based policy making process. There is a growing realization that systematic monitoring is critical for the success of school meal programs such as GSFP. That should be complemented by political commitment to set up an institutional process linking evidence, reform and accountability. One place to start is to gather evidence on factors that contribute to the success of the program at the school level by looking into targeting, operational efficiency, accountability mechanisms and financing. CGD, in partnership with the Institute for Educational Planning and Administration (IEPA) of the University of Cape Coast, is embarking on such a study in Ghana.

Globally, several countries may soon (or already) be in the same position as Ghana: struggling to sustain critical school meal programs in the face of mounting budget deficits and high inflation. This is arguably the most significant test on school meal programs in low- and middle-income economies since the widespread scale-up of national programmes, in the aftermath of the 2008/9 global food crisis.

If the hard-won gains from school meals are to be preserved, adaptive and evidence-driven strategies are essential. It is high time policymakers and international partners get serious about strengthening what works, and reforming what doesn’t.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.