More from the series

CGD NOTES

As global leaders begin to put together an international financing package to help low-income countries (LICs) recover from the COVID-19 crisis, they are looking to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to be a critical financial and policy anchor for LIC’s sustainable economic recovery.

In the immediate response to COVID-19, the IMF has quickly ramped up its lending to LICs. In 2020, new commitments from the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT) were about $9 billion compared to an average of just over $1.5 billion per year over the past five years. Net disbursements (outlays less debt service paid to the Fund) went from less than $100 million per year to $8.5 billion in 2020.

Demand for the IMF’s concessional lending is bound to remain high, as LICs come to the Fund for both financial support and economic guidance. The virus is hitting LICs harder, vaccines are slow in reaching them, and the economic recovery will be prolonged, uncertain, and subject to reversals. Other LIC partners (bilateral donors and multilateral development banks) will want to see an IMF-supported program in place before they disburse their financial assistance. Moreover, G20 countries recently made having an IMF-supported economic program a condition for debt relief from official creditors.

However, the financial structure and current policies governing the Fund’s LIC lending would sharply reduce lending in the next few years back to pre-2020 levels—that is a cut of over 80 percent from 2020 levels, just when LICs are most in need of the Fund’s support.

We propose a five-step plan that ensures sufficient resources are available to meet a high level of demand for new loans over the next few years, and then addresses the longer-term sustainability of Fund concessional lending once it is clearer what that demand will be.

(To understand our proposal, some knowledge of the terminology, structure, and policies surrounding the Fund’s concessional lending is needed. A primer can be found at the end of this blog and a more detailed explanation of both the structure and our proposal is given in the accompanying paper).

- Formally suspend the policies that require the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT)—the source of the Fund’s concessional lending—to be self-sustaining. The notion of “self-sustaining” was to enable the Fund to continue financing LICs at close to $2 billion every year well into the 2030s without recourse to further donor contributions. Strict application of current policies would force the Fund to slash commitments in 2021-23 to preserve its ability to lend to LICs a decade later. This false tradeoff can be avoided by temporarily suspending the self-sustaining model on the understanding that the Fund will work toward putting the PRGT back on a self-sustaining financial footing once the crisis is over. A formal acknowledgment that commitments are not being constrained to preserve the self-sustaining model would also help to reassure LICs of the IMF’s ability to continue to lend at higher levels.

- Suspending annual “reimbursements of PRGT costs” from the PRGT reserve account to the Fund’s General Resources Account. In recent years the costs of running the PRGT—mainly staff time working on PRGT supported programs—have been borne by the PRGT on the grounds that these services are not available to all members of the IMF. Halting this reimbursement would save the PRGT about $87 million per year and, given the Fund’s strong current operating revenue, would not have a material impact on Fund operations.

- Seek additional loan resources from rich countries. This effort is already underway by the Fund and has had some success in 2020. It is worth noting that these monies are lent to the IMF (ownership rests with the rich country) and receive interest, so should be relatively easy to raise. If there is an SDR allocation, rich countries could use their share of new SDRs for this purpose.

- Focus on raising money for the Catastrophic Containment and Relief Trust (CCRT) in 2021, rather than PRGT subsidy resources. The CCRT provides debt relief to PRGT borrowers and is being used for those countries active in the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI). More money is needed if the DSSI is to be extended to the end of 2021 and into 2022. The CCRT requires transfer of resources to the Fund and thus amounts to an expenditure by the donating government. Similar transfers will eventually be needed by the PRGT, but those could be met in a few years from gold sales profits—the final and key step in this plan.

- Begin discussions on the long-term financing of the PRGT, including the possible use of gold sales to replenish the subsidy and reserve accounts. Sales of some of the Fund’s gold reserves were used in the past to make the PRGT self-sustaining at the $2 billion-per-year commitment level. But gold sales require a broad consensus from the Fund’s membership and can only be implemented over a few years’ time. Thus, strategic discussions should begin now. (We’ve written a separate blog on gold sales that you can read here.)

A commitment by the G20 to take these five steps can be made in the first quarter of 2021 and reaffirmed at the time of the Fund meetings in April 2021. This will set the Fund on the road to providing the necessary support as LICs emerge from the COVID-19 crisis and begin to rebuild their economies in a sustainable way.

Background: A primer on the PRGT

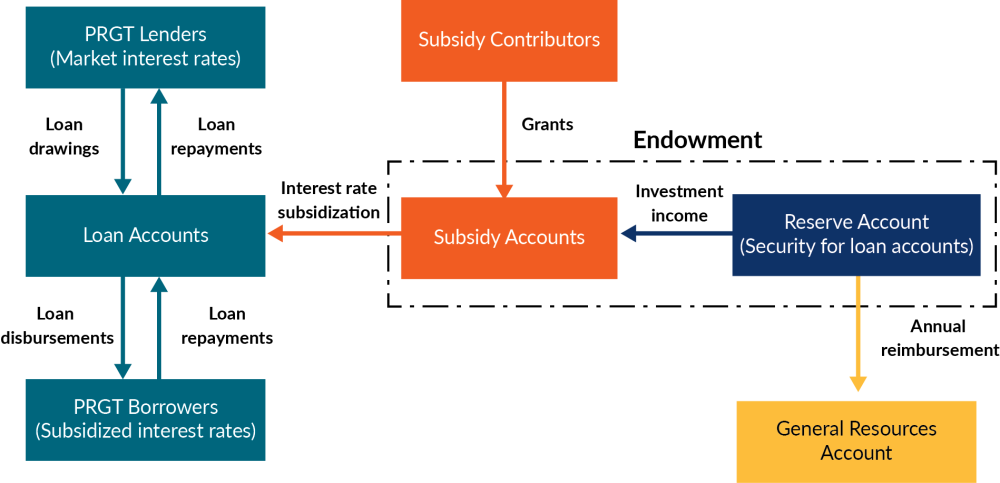

The IMF’s concessional support for LICs is provided primarily through the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT), which is separated from the rest of the Fund’s finances. The PRGT has three accounts as depicted in Figure 1:

- The loan account borrows money from richer countries, paying them a market interest rate (currently less than 1 percent), and on-lends money to LICs, charging them a less-than-market rate, currently 0 percent. Thus, absent any support, the PRGT would make a loss, although with the fall in global interest rates, the loss figure has commensurately been reduced.

- The subsidy account makes up for the interest rate loss, covering the difference between interest paid to rich countries and interest earned from poor countries.

- The reserve account also generates income that will cover interest subsidies when the subsidy account has been depleted. In addition, it

- provides security to rich country lenders to the PRGT that they can be repaid even if LIC borrowers are unable to repay on time; and

- reimburses the Fund’s operating account (the General Resources Account) for the costs of running the PRGT, including staff costs of putting PRGT-supported loans in place.

As the volume of lending from the PRGT to LICs increases, interest losses are higher, thus increasing the need for subsidy resources. Higher lending volumes also call for more reserves as a safeguard for lenders, while the reserve account is charged more for the increased operational costs of the PRGT.

Figure 1. PRGT Structure and Flow Funds

Source: Adapted from IMF publications

In 2014, the PRGT was redesigned as a self-sustaining endowment that can accommodate close to $2 billion in new commitments for the foreseeable future. Income from investing resources in the subsidy and reserve accounts was sufficient to subsidize ongoing lending operations. And reserves would amount to about a third of overall commitments—sufficient to assuage creditors that any late payments by a borrowing LIC could be covered. This design was adopted to ensure a continuing moderate amount of lending to address LICs economic programs to increase growth and reduce poverty, recognizing that the Fund would not be the principal source of financial support for them. In some sense it was designed for a perceived “chronic” amount of moderate support, not for an “acute” crisis where balance of payments need shot up sharply simultaneously for many LICs.

The demand for PRGT resources of $9 billion in 2020 thus puts stress on the PRGT’s long-term sustainability. Before the pandemic, IMF staff estimated that the PRGT could cope with commitments of just over $2 billion a year for a decade without jeopardizing its longer-term capacity. But the surge in lending in 2020 implies that, under the rules of self-sustained framework, the IMF would now need to sharply curtail lending to below even $2 billion just when LICs are most urgently in need of support from the PRGT.

With continued high lending from the PRGT in store for 2021 and 2022, if not beyond, the PRGT’s endowment will require rebuilding to ensure that the IMF can sustain its support for LICs over the longer term. The amount of refinancing needed will depend on the demand for loans from LICs, which, even with all the information available now, is a bit of guesswork. And given low interest rates, some parts of the refinancing need not happen immediately, but should be agreed now as part of an overall financing strategy and executed over the next two to three years. This motivates our five-step proposal spelled out earlier.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.