Recommended

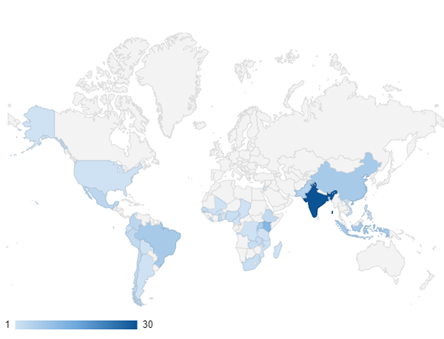

Last month, 3,500 policymakers, practitioners, advocates, researchers, and youth delegates from around the globe descended upon Kigali’s sprawling convention center for the 5th International Conference on Family Planning (ICFP). As the largest gathering of family planning (FP) experts, this blockbuster conference was an important moment for the global community to take stock of accomplishments and lessons learned, share new ideas to accelerate progress, and spotlight FP efforts—like the supply chain data visibility platform—which are relevant across global health. Much of what was discussed intersects with CGD’s previous work as well as with new projects in the pipeline and we were keen to absorb and interpret the latest evidence.

The theme of this year’s conference, “Investing for a Lifetime of Returns,” closely links to CGD’s own research which seeks to ground conversations in rigorous evidence on the causal impacts of access to contraception on women’s economic empowerment. Despite agreement on expanding voluntary FP as the right and smart thing to do, results to date suggest the glass is both half full and half empty. The FP2020 annual progress report, launched at ICFP, points to important gains in the 46 million additional women and girls accessing FP services since 2012. But there was consensus that the ambitious goal of reaching 120 million additional users by 2020 will not be met. And the undeniable reality that the FP community is facing an increasingly uncertain funding and policy landscape (as we’ve highlighted in our work with the Kaiser Family Foundation) also hung over the conference.

In case you didn’t make it to Kigali, here are our key takeaways and the questions they raise:

1. It’s all about the money. . . Or is it?

Much of the buzz at ICFP focused on the money. New data from the Kaiser Family Foundation points to a 6 percent increase in donor support for FP from $1.20 billion in 2016 to $1.27 billion in 2017—a positive trend after two years of successive declines. The slight decrease (~8 percent) in US support was attributed primarily to delays in programming the available funding, possibly due to the administrative processes of rolling out the expanded Mexico City Policy. Many low- and lower-middle income countries rely heavily on US government support for FP, and the roll-out of this policy combined with the implementation of USAID’s Journey to Self-Reliance approach continue to be a source of uncertainty, with potential implications for future programming for both FP and health programs more broadly.

New commitments announced by the Gates Foundation, DFID, and Canada were welcome news. Conversations also focused on the potential catalytic role that new donors like high-net-worth individuals and philanthropic networks could play, specifically in the context of the changing donor landscape, as noted by our colleague Amanda Glassman in her remarks in a plenary session. Also top of mind was government spending on FP, and this year’s FP2020 progress report includes estimates of domestic government expenditure (more on this below).

Ultimately, while total FP financing needs to increase to meet the growing demand, financing alone will not be sufficient; improved policies along with parallel increases in coordination and efficiencies must also be realized to achieve value for money and accelerate access to quality, voluntary FP programs.

2. An ever-more complicated donor ecosystem

FP programming in low- and middle-income countries is becoming further complicated with more decentralized decision making and increasing attention to evolving paradigms of primary health care and universal health coverage. On the donor front, the addition of the Global Financing Facility (GFF), which plans to expand to 50 counties by 2023, adds yet another dimension of complexity to an already complicated donor ecosystem.

The GFF is a new instrument with a purported $7.5 billion programming budget through the World Bank’s IDA/IDRB financing mechanism; the urgency to better understand its planning and programming processes were top of mind for many at ICFP. FP is reportedly central to the GFF strategy: expanded access to voluntary FP accounts for one-third of the estimated 35 million lives that could be saved by 2030.

ICFP participants gave mixed reviews to GFF’s planning processes to date. It’s early days for the GFF and, like many other newly minted multilateral entities, GFF is learning as it is doing. The GFF is already demonstrating institutional responsiveness to feedback; we learned that requests for a more inclusive planning process will be accomplished by adding technical experts within the Secretariat and GFF liaison officers in the field to help the GFF mechanism interface more closely with the World Bank in some countries.

Another bit of good news/bad news: GFF recipient countries must meet World Bank effectiveness and other regulatory requirements, a helpful incentive for reinforcing countries’ fiscal management systems. But the release of GFF funds was delayed in some instances, which can endanger regular shipments of FP and other health commodities.

GFF’s potential impact on FP coordination and aligning donors around nationally defined and owned goals is something CGD has been and will be following. How, and how well, the GFF coordinates its results-focused approach with existing FP funders in practice remains an open question, and is in many ways parallel to an early challenge FP2020 also faced.

3. More data is a step in the right direction, but quality matters too

A large amount of data—ranging from population and fertility projections from IHME to key indicators collected via rapid, low-cost mobile surveys by PMA2020—were released in the run-up to and featured at ICFP.

The FP2020 annual report, for the first time, included validated estimates of government expenditures on family planning for 31 countries (see indicator 12). This information could potentially serve a valuable role in holding commitments to account and providing a baseline for future FP spending. But in practice, it’s extremely challenging to directly measure government FP expenditures; this is highlighted by the fact that the estimates are from four different sources, each using distinct methodologies and cover years ranging from 2011–2016. Recognizing that the process of developing these estimates was extremely resource intensive, it’s a step in the right direction—and we hope to see both the methodology and practical use of these types of data evolve going forward.

4. Momentum on building the FP evidence base

While raising sufficient funds and tracking how financing is allocated is important, we also need rigorous evaluation to know if programs are driving impacts, achieving efficiencies, and reaching intended populations. So we were pleased to see new evidence showcased at ICFP, including preliminary results from impact evaluations of programs addressing barriers to FP access in Malawi and Nepal, among others. Despite positive momentum, rigorous measurement of impact at scale and performance measurement in this space are still rare. And data on costing of FP programs are particularly hard to come by. These data are critical for decisions around scaling programs and are also relevant for transition planning, where it is important for entities that become responsible for future funding to fully understand what they are taking on.

5. What’s next? The future is now

2019 begins in a few short days, and 2020 is right around the corner, so the question on everyone’s minds is what’s next? We’ve heard that the post-2020 approach will be defined through an inclusive consultation process to strengthen the FP movement through engagement and consensus building. Accordingly, a top question will be what has worked well and what might be done differently. Having watched FP2020 since its inception, we offer a few observations.

What worked well? The partnership has driven inclusive communication among key leadership through its Reference Group as well as regularized communications and cross-education among organizations and constituencies central to increasing FP access, including the Reproduction Health Supply Coalition, faith-based communities, and civil society. It has also served as a central repository of data across the 69 FP2020 countries, and as such created incentives to regularly collect and transparently publish new data.

There are also learning opportunities for the future of FP2020 and related initiatives. The early Costed Implementation Plans, while well intentioned, were challenged by not linking directly and pragmatically with financial flow planning. FP2020 is now a mature movement and is well positioned to share these lessons with other actors, like the GFF as its own planning and implementation processes evolve. Also, FP2020’s initial policy and advocacy engagement focused on many who were already considered FP champions; more recently though, its approach has shifted to engaging a greatly expanded cadre across multiple sectors—moving beyond the FP and global health-focused communities by linking clear data on FP impact and costing with individual, family, community, and country level development gains.

Over the coming months, CGD will continue to contribute research and analyses on the global FP landscape with a focus on understanding the impacts of unpredictable funding flows and identifying approaches to drive sustainable financing for FP in the context donor transition and evolving universal health coverage goals. Stay tuned!

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.