CGD’s ongoing work on data governance and economic development focuses on how societies can best balance the social good that having better information can provide with the need to protect individual rights. The COVID-19 pandemic puts this challenge in the starkest terms.

Responding effectively to public health emergencies requires timely and accurate information. As the COVID-19 pandemic has progressed, the effectiveness of national efforts to combat the virus has hinged on the ability of governments to measure its spread and use that information to target their public health efforts.

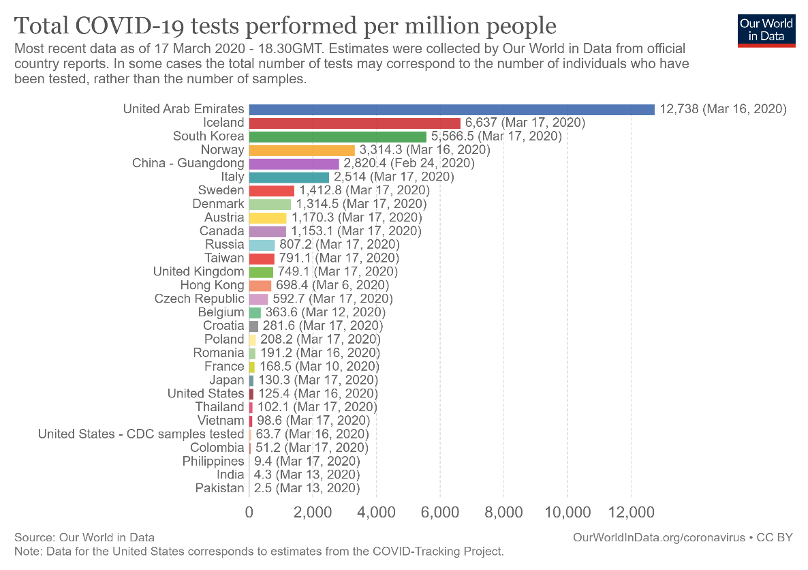

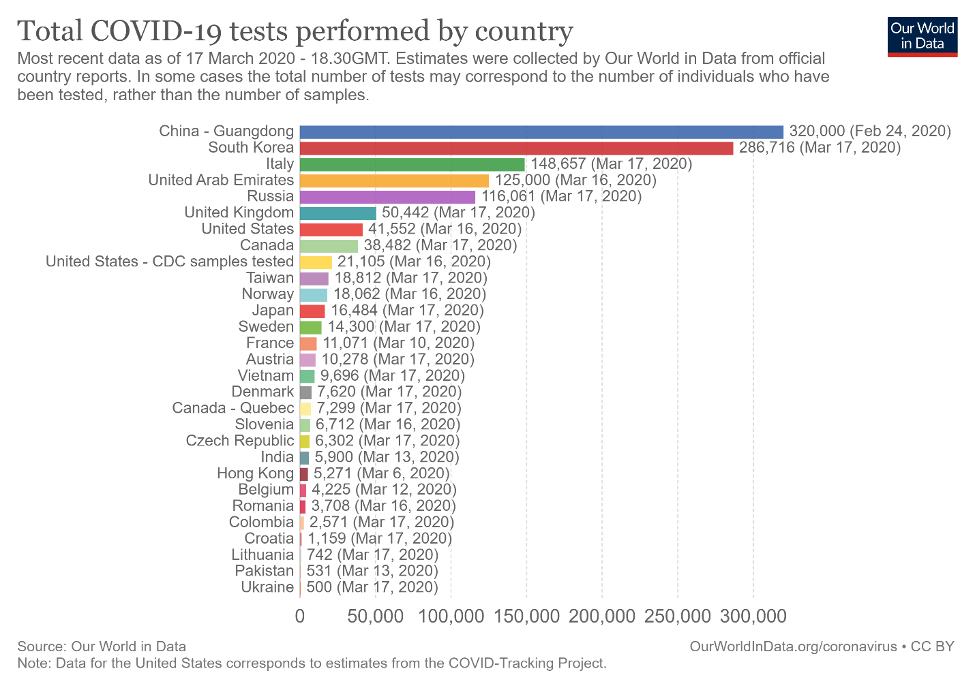

The world’s response to the pandemic has been marred by information failures from the outset, starting with China’s early attempts to silence reporting about the scale of the problem within its borders and continuing through the slow rollout of diagnostic testing in many countries, most notably the United States. The resulting lack of visibility about the virus’ spread has handicapped the global response.

Countries that have performed better in the early days of the pandemic have done so through a combination of more widespread testing, more effective contact tracing (i.e. identifying and monitoring people who have been in close contact with someone infected), and isolation of infected patients. Asian countries have gone the farthest in their contact tracing efforts, building upon systems and tools developed in the aftermath of dealing with SARS and (in the case of South Korea) MERS that rely on a combination of on-the-ground detective work and the use of invasive digital tools to track people’s movements. For example:

In South Korea, the government obtains information from a variety of sources including CCTV footage, cellphone records, and credit card receipts of “confirmed COVID-19 patients” to post “the precise movements (without names) of everyone who tested positive — everything from the seat numbers they occupied in movie theaters to the restaurants where they stopped for lunch.” (Source 1, Source 2)

Similarly, in Singapore, the government maintains an online dashboard that provides detailed information about each positive COVID-19 case. For example Case #199 refers to a 37-year-old man who traveled to Malaysia between February 26 and March 2, where he attended a mosque linked to several other COVID-19 cases. The website also provides the name of the street where the man lives and notes that he works as a food delivery person for the company GrabFood and visited a (named) mosque in Singapore.

In Taiwan, the National Health Insurance Administration (NHIA) and the National Immigration Agency combined their databases to enable the government to track the 14-day travel histories of citizens alongside health information tied to their NHI identification card. Individuals identified as high risk are then monitored electronically through their mobile phones. (Source)

China is rolling out a nationwide system that uses an app (Health Code), which users can sign up for through Alipay or WeChat, to assign color codes (red, yellow, or green) to each person based on their travel history and self-reported health condition. The assigned codes determine whether and to what a degree a person’s freedom of moment will be restricted. For example, “a green code enables its holder to move about unrestricted. Someone with a yellow code may be asked to stay home for seven days. Red means a two-week quarantine.” (Source 1, Source 2.)

In India, a district government in the state of Kerala used geo-mapping of quarantine locations, CCTV recordings, and call record data to “track down over 900 primary and secondary contacts of a family who returned from Italy carrying the COVID-19 infection.” (Source)

Countries outside of Asia are pursuing similar approaches. Earlier this week, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced plans to use the same digital technologies the country uses to monitor terrorist groups to track the spread of COVID-19, noting that “in all my years as prime minister I have avoided using these means among the civilian public but there is no choice.” (Despite Netanyahu’s stated reluctance, it is worth emphasizing that this previously undisclosed system and the trove of cellphone data it collected already existed.) In the United States, state agencies are reportedly in discussions with Clearview A.I. Inc. and Palantir about ways to use facial recognition and data mining technology to track infected patients, while the federal government is exploring using geolocational data provided by Google and Facebook and other tech companies to monitor spread of the virus.

[For more information on the surveillance measures governments are taking to combat COVID-19, you can visit this tracker from Privacy International.]

Digital Surveillance in Sickness and in Health

While the term “surveillance” has a negative connotation in most contexts, in the field of public health, it is an essential tool for responding to emergencies. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines public health surveillance as “the continuous, systematic collection, analysis and interpretation of health-related data needed for the planning, implementation, and evaluation of public health practice” and calls it the “bedrock of outbreak and epidemic response.”

Increased reliance on digital tools to monitor the spread of disease raises serious questions about how to prevent governments from using those same tools to track individuals for other purposes after a health crisis has subsided.

The ubiquity of mobile phones and the increasing share of economic and social activity conducted online has made it easier than ever to track people’s movement through their digital footprint. It is therefore inevitable that public health surveillance will increasingly be conducted through digital means. But increased reliance on digital tools to monitor the spread of disease raises serious questions about how to prevent governments from using those same tools to track individuals for other purposes after a health crisis has subsided.

Policymakers must make a difficult choice when deciding whether to invoke extraordinary surveillance powers during a crisis and how invasive those measures should be. While the privacy community has focused on how surveillance measures threaten civil liberties, a lack of effective monitoring can also undermine freedom. Take, for example, the cases of France, Italy, and Spain, where, due to a lack of testing and monitoring and the resulting uncertainty about where COVID-19 is spreading, national governments have deemed it necessary to put their entire populations on lockdown (the same situation is now happening in California, with other countries and US states likely to follow suit).

More importantly, novel digital surveillance measures may also save a massive amount of lives. Epidemiologist Trevor Bedford argues in a lengthy Twitter thread that “using cell phone location data combined with data on known positive cases to alert possible exposures to self-isolate and get tested” is one of three strategies that should be combined to combat the pandemic (along with a massive rollout of testing capacity and allowing people who have recovered from COVID-19 to return to the workforce). His analysis on the potential of using mobile phones for contact tracing draws from this paper by Oxford researchers, which argues that “isolation and contact tracing as currently practiced is unlikely to prevent an epidemic.”

I've been mulling over the @MRC_Outbreak modeling report on #COVID19 mitigation and suppression strategies since it was posted on March 16. Although mitigation through social distancing may not solve things I believe we can bring this epidemic under control. 1/19

— Trevor Bedford (@trvrb) March 19, 2020

At the moment, governments are rushing to put digital surveillance systems in place without due process or informed debate within their societies. While it will be difficult for policymakers to engage in thoughtful debate around these tradeoffs amid a crisis, it is both necessary and possible (as highlighted by a letter sent by several Democratic senators to Vice President Pence that raises privacy concerns about the government’s plan to work with Google and other tech firms to combat COVID-19).

The good news is that there are ways to preserve the flexibility governments need to combat the spread of the virus while maintaining a framework that guarantees civil liberties. The Electronic Frontier Foundation suggests the following guidelines for policymakers considering implementing new data collection and digital monitoring exercises:

Privacy intrusions must be necessary and proportionate. Activities must be deemed medically necessary by public health experts and any new processing of personal data must be proportionate to the actual need.

Data collection based on science, not bias. Governments must ensure that any automated data systems used to contain COVID-19 do not erroneously identify members of specific demographic groups as particularly susceptible to infection.

Expiration. Governments and the companies they work with to extend surveillance must roll back any invasive programs created in the name of public health after the crisis has been contained.

Transparency. Any government use of “big data” to track virus spread must be clearly and quickly explained to the public.

Due process. If the government seeks to limit a person’s rights based on “big data” surveillance, then the person must have the opportunity to timely and fairly challenge these conclusions and limits.

A Post-Crisis Agenda

Even though we are still in the early days of dealing with COVID-19, it is not too early to consider what rules for governing the use of digital surveillance should be in place before the next health crisis arrives. Starting on this process early in the next interpandemic period will be crucial since having these conversations during a crisis is so challenging.

One obvious starting point is revising the WHO’s Guidance for Surveillance During an Influenza Pandemic and its Guidelines on Ethical Issues in Public Health Surveillance, both published in 2017. The latter document outlines a set of 17 guidelines aimed at “helping policymakers and practitioners navigate the ethical issues presented by public health surveillance.”

These guidelines are generally well-aligned with foundational privacy principles, including the OECD Privacy Guidelines and the Privacy by Design Principles, but they do not consider many of the risks presented by the novel digital surveillance measures that countries have enacted in response to COVID-19. For example, the guidance only briefly mentions the risks that governments create when they rely on private corporations to conduct digital surveillance.

Another crucial omission is any discussion of the need to unwind extraordinary surveillance activities after a crisis has passed. If societies agree that it is legitimate to enact measures that bypass the need for consent during times of crisis, there must be mechanisms in place to unwind those measures once circumstances change. For that reason, the WHO should urge governments to enact sunset clauses that automatically terminate emergency surveillance measures after a specific date or in response to a triggering event, unless further legislative action is taken.

On #privacy and #coronavirus: we shouldn’t resist the use of tech to track, predict, make people aware, help those most at risk. We *should* fight to keep its impacts and benefits equal for everyone, we should resist its normalisation and we should demand its reversibility.

— linnet taylor (@linnetelwin) March 14, 2020

As the WHO seeks to revise its guidelines, the public health community should inform debate by providing evidence on the effectiveness of different digital surveillance measures. This is important because the effectiveness of such measures has been overstated in the past, including during the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. A recent CGD paper outlines five key technical considerations for researchers seeking to build evidence on the effectiveness of different pandemic responses.

At the national level, governments should enact legal frameworks that govern the use of digital surveillance during a health crisis in line with the principles referenced above. Creating and implementing these frameworks will likely be easier in countries that have a holistic data protection framework and an agency dedicated solely to data protection. In this regard, it is worth highlighting the recent statement by the European Data Protection Board that emphasized the responsibilities of data controllers to ensure the protection of personal data while also noting that the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) provides the legal grounds for employers and public health authorities to “process personal data in the context of epidemics, without the need to obtain the consent of the data subject.”

Legal scholar Laurence Tribe describes privacy as “nothing less than society’s limiting principle” (a quote referenced in Sarah Igo’s The Known Citizen). Societies may choose to relax the limitations on how much information governments should have about their citizens in times of crisis, but this loosening needs to be done in a principled and thoughtful manner. If instead we allow governments to ratchet up surveillance measures during a crisis without institutionalizing a process for ratcheting them down after that crisis passes, we will end up with a system that fails to reflect our values.

Ugonma Nwankwo provided research and editorial support for this post.

I’m grateful for comments provided by Anit Mukherjee, Kalipso Chalkidou, Carleigh Krubiner, Tom Orrell, Rachel Silverman, and Prashant Yadav.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.