The 2019 UK Conservative Party manifesto committed the UK government to “stand up for the right of every girl in the world to have 12 years of quality education.” Girls’ education has been at the heart of the Department for International Development’s (DFID) education policy and programming since 2012 and Prime Minister Boris Johnson has personally championed the issue since his tenure as Foreign Minister, calling it the “Swiss Army knife” that solves a multitude of the world’s problems.

The commitment is laudable and, as one of the main aid pledges in the Conservative Party manifesto, it will be a high-stakes goal for DFID during this parliament. The UK is already the second-biggest donor to schools in the developing world, and generously provides around £1 billion per year to education. But 12 years of school for every child has been estimated to cost an additional £30 billion a year. UK government money will need to be used strategically to leverage influence and funds from elsewhere if it is to achieve their goal.

We offer five recommendations to help the UK government deliver on its manifesto commitment.

-

Learn how to make schools safe: Too many girls (and boys) are not safe at school. We do not know enough about the levels of violence in school nor the practical and policy levers to address it. The UK government should rapidly and significantly ramp up efforts to better monitor, measure, and eliminate violence in schools.

-

Break down barriers to entering the labour market: Girls need to see that they can use their human capital once they leave school. It’s important to change norms and aspirations through role models and accurate information on the returns to schooling, yet evidence and proven interventions are limited. the UK government should address this. On the demand side, it should work with governments, industry, and aid donors to mitigate barriers to labour-market entry and invest in industries that promote female employment.

-

Help developing country governments find ways to eliminate financial barriers: Cost barriers are highly context specific. The UK government should support governments to find the most effective ways to eliminate financial barriers, especially in poorer, more remote, and weakly governed contexts where gender disparities in enrollment persist.

-

Invest in better quality of education for girls and all children: Students derive the greatest benefits from school when their time there is spent developing effective skills. Many of the best investments to improve the quality of schooling for girls ultimately benefit all children. DFID has helped build vital knowledge on quality, for example through its support to the RISE programme, and the UK government should continue to look for and influence the scale-up of evidence-based interventions to improve learning.

-

Seize the global agenda: DFID should take a lead role in sorting out the education aid architecture so that girls benefit through money being spent better, via the most efficient channels, and in the places with the greatest need.

Below, we lay out the big picture context and the evidence underlying each of these recommendations.

The Big Picture Context

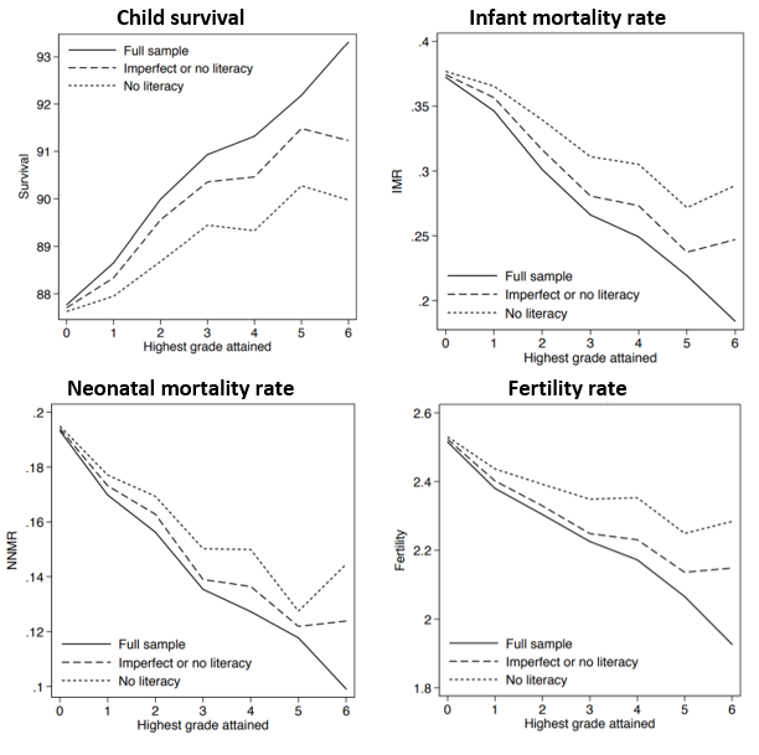

Prime Minister Boris Johnson is right to want to get girls into school. Girls schooling in and of itself is a social good: We know that more and better education for girls can translate into more jobs, better health, fewer teen marriages and pregnancies, and many other benefits that extend into the next generation. And, while it’d be nice if girls learn something while they’re there, even where learning levels are extremely low, the predicted social returns to schooling are still high (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Schooling benefits girls, even if they haven’t learned to read

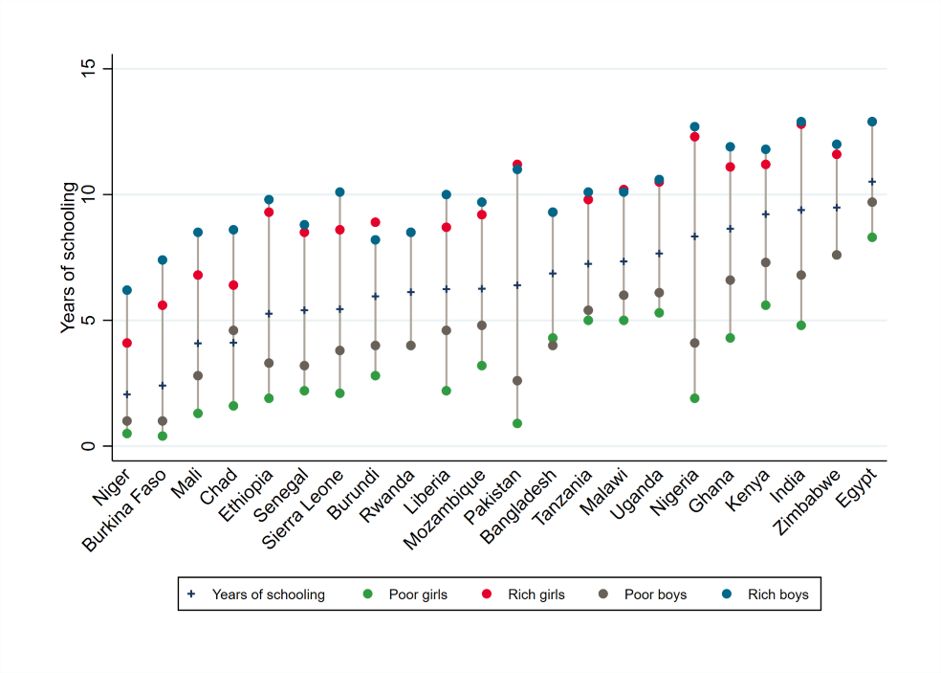

One hundred and thirty million girls of school age are not in school, and many of those in school are not learning very much. While relative parity in primary school enrolment has been achieved in most countries, this masks acute, context-specific gender gaps (see figure 2). Put simply, girls consistently attain fewer years of schooling than boys, and the poorest girls attain the fewest years. Beyond years of education, schools all too often reinforce negative gender stereotypes for girls and boys, limiting the benefits of human capital for women once they leave school. A lot of progress has been made in the last decade, but much remains to be done.

Figure 2. Years of schooling for richest and poorest girls and boys

Source: authors’ analysis of DHS data

Recommendation 1: Learn how to make schools safe

Every child should be able to learn in a safe environment. But for far too many girls (and boys) school is not a safe place. The UK government should ramp up efforts to monitor, measure and address school-related gender-based violence.

Sexual violence against girls is widespread. One in four girls in developing countries is coerced in their first sexual intercourse. Twenty percent of girls in Zimbabwe are sexually assaulted travelling to or from school. Once they get to school, girls being pressured into sex for grades or fees is rife. A real risk of rapidly expanding girls schooling is an increase in violence.

Schools should help make girls safe both immediately whilst at school and in the longer term by changing social norms.

Make schools safe for girls: Distance to school is often the most important factor for parents in school choice, and it especially matters for girls. It’s not just a travel nuisance but reflects safety concerns too. Providing safe transport can make a real difference—even distributing bicycles to girls. Where new schools do need to build, the UK government can lend expertise in data mapping to optimise placement. Once girls have reached school, there is some evidence that school-level interventions can make schools safer. A common intervention is to train teachers on safeguarding, how to spot cases of violence, and how to take appropriate actions. More systemic approaches include working with all actors of the school, and notably the leadership of the school, to address areas such as school ethos, school management, raising awareness of school staff, or instituting a referral system. Whole-school approaches are often embedded in broader educational support programs or in programs against all types of violence in school. A systematic review suggests that there is some promising evidence for school- or community-based programs that promote women’s agency and encourage changes in norms for women and men to prevent violence against women and girls in low- and middle-income countries.

Use schools to make society safer for women and girls: Schooling can also reduce gender-based violence by raising women’s income and improving female autonomy and agency. Evidence suggests that having completed secondary education reduces the likelihood of women becoming a victim of intimate partner violence, and also reduces the likelihood that men become perpetrators of violence.

Beyond this evidence, there is limited understanding of the most effective and practical policy levers for school-related interventions that could make schools safer for girls. There is also a gap in our knowledge of current levels of school-related gender-based violence because of a lack of systematic data collection, methodological issues related to measurement, and a big question mark over the credibility of existing numbers. Being able to read more is a secondary concern to being safe in school and the UK government should rapidly ramp up efforts to better measure, monitor, and eliminate violence against girls in school.

Recommendation 2: Break down barriers to entering the labour market

Role models and aspirations matter. We have reams of data on this. So it was a woeful capitulation when (probably) the best aid agency in the world cut funding for the “Girl Effect” project in Ethiopia—an all-girl band termed the “Ethiopian Spice Girls” —because of the frothy-mouthed ravings of the tabloid press. The UK should back innovative projects like this designed to address the sexist beliefs that hold girls back, while also working to address demand-side barriers to the labour market.

Schools and teachers can instil negative gender norms that adversely affect girls’ academic performance, and—even beyond the impact on enrollment or learning—shape gender norms in society once children leave school and curtail girls’ career aspirations and their labour force participation. If we want to equalize women's opportunities, it is not enough to equalize educational outcomes and hope that the market does the rest.

School-level changes such as facilitated class discussions, youth clubs, and scrapping sexist textbooks can play a role in shaping gender norms and aspirations. Role models also shape girls’ aspirations. For example female teachers help boost attainment and learning for girls, and at no cost for boys.

Changing career aspirations requires more than encouragement and investment in skills. Real job opportunities for women are also needed. When new service and light manufacturing job opportunities opened up in India and Bangladesh, parents responded rationally by investing more in their daughters’ education.

Research is in its infancy on methods to elevate girls’ post-school aspirations, to use education to reshape gender norms to reduce gender inequality, and to address labour market barriers to allow women to use their human capital. The UK government should prioritise investment in innovative programmes and research in this area. It should use its influence with development finance institutions and private sector partners to strategically leverage political and commercial relationships, with the Foreign Office playing an important role, to promote female economic empowerment.

Recommendation 3: Help Governments find ways to eliminate financial barriers for girls

Cost is a key barrier to education for girls. The most important costs depend on the context. The UK should help countries to innovate and test different approaches to find the most cost-effective policies in their context.

Even relatively small financial barriers can matter. A range of programmes that cut costs have shown strong results—from cutting school fees, to scholarships or stipends, cash transfers, or even simply handing out free school uniforms.

But effects, and cost effectiveness, can vary dramatically by programme design and by context. The UK can add significant value by helping countries understand and adapt global evidence to work out what works best in their country. This is particularly the case in the hardest remaining places. The evidence base is weakest for precisely the remote and fragile locations where the girls schooling challenge is greatest.

We should also remember that in many cases girls education should be tackled as part of an agenda that also tackles educational opportunities for boys, not least because interventions that target boys and girls might be among the most successful at improving outcomes for girls.

Recommendation 4: Improve the quality of education for girls and all children

Too many girls are attending school but not learning. Only about half of girls in Ugandan and Tanzanian primary schools are achieving competency in mathematics. Similarly low numbers appear in a range of low- and middle-income countries. Even though there are some benefits to education in the absence of literacy, it is a massive waste to send children to school for years and have them exit with few academic skills they can put to work in the marketplace and in their homes.

Recent evidence shows clear ways to improve the quality of education. A holistic literacy intervention in Kenya that provides training and coaching to teachers along with detailed teacher guides and lesson plans significant improved early literacy and has been scaled up across the country. Teacher coaching interventions in Peru and South Africa have boosted test scores. A subset of technology interventions—individualized learning in India and teacher technology tools in Uganda—have also proven effective. In some contexts, providing incentives for teachers based on their performance has boosted learning. The right approach will depend on the specific challenges faced in each context.

What’s more, the most effective interventions at improving the quality of education for girls often improve the quality for boys as well. In many countries with poor learning outcomes for girls, learning outcomes are likewise poor for boys. If investments to ensure 12 years of quality education for every girl have the added benefit of providing comparable skills and opportunity to the boys those girls interact with, the world will be better off. The UK has a history of investing both in knowledge on how to improve the quality of schooling and then in seeking to nudge investment money in favor of that knowledge. We need more of that.

Recommendation 5: Seize the global agenda

The global education policy system is a wild west. There ten different targets for the 2030 Sustainable Development Goal on education, and countless indicators. As the second biggest donor, the UK can influence country-level decision-making and leverage the spending of others by playing an active leadership role in shaping which global goals get most attention.

One way to do this would be to lead the charge for a high-level internationally agreed measure on whether girls have actually achieved 12 years of quality education, something we’re still lacking. The UK can and should lead on the development and monitoring of this indicator. More broadly, DFID should step up its efforts to strengthen the education aid architecture so that it provides the leadership, finance and data that the education sector so desperately needs. And, since DFID is better and more transparent at spending aid money than the Foreign Office, the UK government should drop any plans to abolish DFID as a standalone department.

Post-script: Equalising schooling isn’t enough. If the UK government truly cares about gender equality, it must look beyond education.

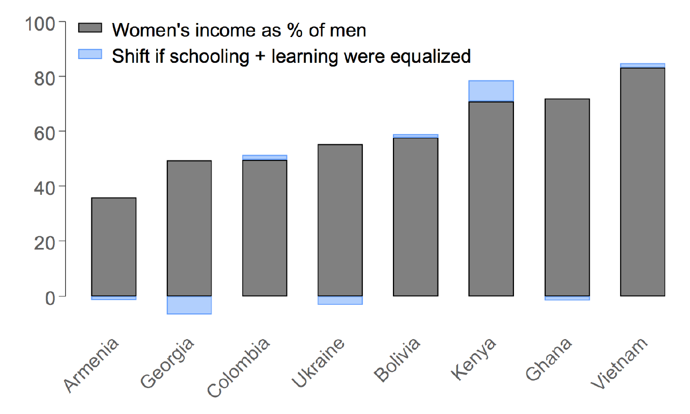

Getting girls into good schools solves just one part of the problem of gender inequality, but it is not enough to achieve equal life outcomes for women. Even in the UK, where girls outperform boys in school, women are paid less at work and are under-represented in leadership positions. The gap in earnings between men and women is enormous in many parts of the developing world (see figure 3) and gender parity in education would not do much to close that gap. Standing up for every girl’s right to education is the right thing to do but, if the UK government’s ultimate aim is gender equality, it must also pay attention to why equal education is compatible with such unequal social outcomes.

Figure 3. Schooling and learning does not explain the gender pay gap

Source: CGD analysis of World Bank STEP surveys from urban labor markets, based on Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition. Note: Individuals who do not work are assigned zero income

Thanks to Alexis Le Nestour and Rita Perakis for their helpful comments.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.