Recommended

Introduction

The IMF’s Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT) faces very large financing needs. Recent CGD blogs (see here and here) highlighted the scale of these needs and the implications for the IMF’s lending to low-income countries (LICs) if they were not met. Simply put, unprecedented levels of lending since the start of the pandemic – four to five times higher than before the pandemic – have seriously depleted the PRGT’s subsidy resources. If these are not replenished the PRGT’s lending capacity from 2025 onwards would collapse to well below its pre-pandemic level. And such a withered PRGT, able to lend less than SDR 1 billion a year, would not come close to meeting LICs’ needs.

This note considers options for restoring the sustainability of an appropriately sized PRGT. There are no easy solutions – all options face obstacles or have their own drawbacks. And since they would yield different results over different time horizons, the best approach will very likely be a combination of steps, with some serving as a bridge to a longer-term resolution. The suitability of the various options also depends on how much financing the PRGT needs. This in turn will depend on the desired size of the PRGT and its future role.

The note is structured as follows. We begin a short summary of the PRGT’s unusual financial structure and IMF fund-raising to date. (Readers familiar with this background may wish to skip this section). We then argue that for myriad reasons a larger PRGT is needed and conclude that a lending envelope in the region of SDR 2.65 to 3.0 billion would be appropriate. The discussion of funding options begins by summarizing the total financing need before turning to look at the various funding possibilities. Donor contributions as straight cash grants typically require budget approval but other options are also set out. The pros and cons of the two main avenues for IMF financing – gold sales and (indirect) use of some of the IMF’s reserves – are discussed. The note then examines the savings from eliminating the requirement that the PRGT annually reimburses the IMF for its operating costs and then looks at the implications of other changes to the financial architecture, including charging higher interest rates to borrowers and paying lower rates to lenders. This section of the note then concludes with a brief discussion of priorities and how various options could be combined. Since there are no easy solutions – and a risk that funding could fall short – we conclude by sketching a possible alternative to the existing financing model.

The PRGT’s structure and current financing needs

Before the pandemic the PRGT had a ‘self-sustaining’ annual lending capacity of about SDR 1.4 billion. If lending commitments averaged no more than SDR 1.4 billion a year, the resulting subsidy costs could by covered – indefinitely in principle – without the need for any injection of new subsidy resources. This benign outlook was possible because the PRGT had large subsidy and reserve accounts – both about SDR 4 billion in 2019. Together they could generate enough investment income to cover the gap between the subsidized rate of interest (currently zero) paid by LICs borrowing from the PRGT and the SDR rate of interest paid on the loans from rich countries that are on-lent to LICs. This investment also covered the administrative costs (mainly staff costs) of running the PRGT; the reserve account would reimburse the IMF administrative budget (or strictly speaking the General Resources Account, GRA) for these annual costs. The total size of subsidy and reserve accounts (effectively an endowment) is the primary determinant of the PRGT’s self-sustained lending capacity.

Figure 1. The financial structure of the PRGT

Source: Adapted from IMF publications

The pace of lending since the start of the pandemic has been much more rapid. In 2020 loan commitments, mostly in emergency financing from the PRGT’s Rapid Credit Facility (RCF), were over SDR 6 billion. This pace continued in 2021 as LICs sought financing under more typical three-year arrangements from the PRGT’s Extended Credit Facility (ECF). These high levels of lending were obviously far beyond the PRGT’s self-sustaining capacity. De facto, the self-sustaining model was set aside. The much higher level of loan commitments implied that the balance of the subsidy account – and not just the income it generated – would be drawn down to meet the subsidy costs over the 10-year life of these loans. This would then reduce the future lending capacity of the PRGT unless the subsidy account was replenished.

The IMF launched an initial round of fundraising for the PRGT in July 2021. This set a target for new subsidy resources of SDR 2.8 billion, of which SDR 2.3 billion was sought from IMF member countries. The remainder was to come from IMF ‘internal’ resources; reimbursement of the GRA was suspended for five years, thus saving SDR 0.5 billion that would have been debited from the reserve account. The total subsidy amount of SDR 2.8 billion, which was to be in place by end 2024, was intended to do two things. First, to offset the costs of higher lending expected through 2024 (of about SDR 1.7 billion) and second, add (about SDR 1.1 billion) to the endowment to raise the self-sustaining lending capacity of the PRGT to SDR 1.65 from 2025. (For an explanation of these estimates see Box 1 of this paper). At the time, the pace of PRGT lending was expected to ease back from over SDR 6 billion a year in 2020-21 to SDR 3 billion per year in 2022-24.

The subsidy needs of the PRGT have increased further since then. In an updated assessment in April 2023 the IMF estimated in that PRGT would require SDR 2.3 billion in addition to the SDR 2.8 billion sought in July 2021. PRGT lending is now expected to average SDR 6.5 billion in 2023 and 2024 (up from the earlier estimate SDR 3 billion per year). In addition, reflecting the sharp rise in interest rates over the last 18 months, the average SDR interest rate paid on loans to the PRGT is now expected to be about 3 percent (up from 1.5 to 2 percent in the earlier estimate), adding to the demands on the subsidy account, as the interest rate borrowing countries pay has been held at zero. Consistent with the earlier estimates, if these additional amounts are forthcoming, the PRGT would have sufficient subsidy resources to lend SDR 1.65 billion from 2025 onwards.

These fundraising efforts for subsidy resources have so far fallen short. In the two years since the initial round was launched pledges of new subsidy resources totaled some SDR 1.4 billion, leaving a shortfall of SDR 0.9 billion from the initial target of SDR 2.3 billion from member countries.[1] The IMF’s contribution of SDR 0.5 billion was assured by the suspension of reimbursements to the GRA but this still left a total shortfall from the revised estimate of subsidy needs of SDR 3.2 billion. In the absence of further subsidy contributions, this would imply a decline in the PRGT’s lending capacity to just under SDR 1 billion from 2025. In contrast, efforts to bolster the PRGT’s loan resources – the main avenue that countries have used to recycle their excess SDRs – have been much more successful and a buffer of unused lending commitments is now in place. Since subsidy and not loan resources are the key constraint on the PRGT’s capacity, this paper discusses only the former.

And a larger PRGT is needed…

Even if the current subsidy gap is closed, the PRGT will be underfunded for the longer term. The envisaged capacity of SDR 1.65 billion per year that will emerge if an additional SDR 3.2 billion can be mobilized will not suffice. As the IMF has noted, at SDR 1.65 billion the PRGT’s lending capacity would in real terms be broadly equivalent to its pre-pandemic capacity of SDR 1.4 billion. But a range of adverse developments point to the need for a larger PRGT.

The relatively benign global economic environment before the pandemic has been swept aside by multiple crises. Some, such as the disruption to food supplies from the war in Ukraine, may ease over time. But other adverse developments, including the growing impact of climate change, rising debt vulnerabilities in mainly LICs, and the pressures on rich countries budgets are likely to have a lasting impact on PRGT demand.

Climate change is likely to weigh heavily on the most vulnerable countries and increase the magnitude and frequency of adverse shocks. The IMF’s newly created Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST) should over the longer-term help countries to build resilience to climate change, but it will not be able to eliminate vulnerabilities or the impact of larger shocks. The PRGT is thus likely to remain essential to meeting LICs’ balance of payments needs, including additional needs driven by the adverse effects of climate change. This should not be seen as expanding the purposes of the PRGT. Rather the PRGT would continue to meet the balance of payments needs of countries with “protracted balance of payments problems”, including those that have been exacerbated by climate change. It is possible that the RST could meet some of LICs’ longer term financing needs that would otherwise be met by the successive PRGT arrangements. However, we do not expect this to have a significant impact on the overall demand for PRGT resources. As currently structured, access to the RST requires a accompanying PRGT (or GRA) arrangement. The distinct purposes of the RST and the PRGT also suggest that they should not be seen as competitors. From the perspective of potential borrowers, the RST’s longer 20-year maturity may appear more attractive but as interest rates have risen the cost of borrowing from the RST – which is currently not subsidized – has risen sharply for all borrowers including LICs. Thus, while the impact is difficult to quantify, there is little doubt that climate change will add to the demands on the PRGT.

LICs’ need for PRGT financing will also be indirectly affected by budgetary pressures in rich countries. Aid budgets are severely constrained, in part by the legacy of exceptional spending by rich countries during the pandemic. This has effectively ended bilateral aid in the form of budget support, making it harder to close financing gaps in PRGT-supported programs. While MDBs have increased their own budget support, the PRGT is likely to play a larger role in closing financing gaps.

The severe setbacks that LICs suffered during the pandemic will have a lasting effect on the demand for financing from the PRGT. The long-term sustainability of the PRGT relies not just on a large endowment. In addition, the number of countries requiring support from the PRGT was expected to gradually decline. Over time, rising per capita incomes and increased sustainable access to private capital should allow countries to move to ‘blended’ access (using both the PRGT and borrowing on non-concessional terms from the GRA) and ultimately ‘graduate’ from PRGT eligibility. In this way, inflation’s usually slow erosion of the PRGT’s lending capacity in real terms can be balanced by a long-term trend of reduced demand as countries graduate from the PRGT. But the scarring of the pandemic, which will postpone graduations, and the likelihood that inflation will remain higher for some time has thrown this balance off kilter. A larger lending capacity will be needed to meet longer term demand from more countries than anticipated.

The PRGT should also have a larger buffer to cover future emergencies. The PRGT’s large scale lending provided much-needed support in the pandemic. But the resulting collateral damage to the PRGT’s finances now threatens its very existence. It would be unrealistic – and very costly – to build an endowment large enough to accommodate higher lending for all possible tail events, such as a repeat of the pandemic. But a larger lending capacity that explicitly errs on the side of caution by building in buffer for future periods of high demand would make the PRGT itself more resilient to larger and longer-lasting shocks.

Rising levels of debt distress could be seen as an argument against a larger PRGT. Grants or highly concessional loans are more suited to the needs of indebted and fragile LICs. IDA’s highly concessional loans have a grant element of about 50 percent but the relatively short maturity of PRGT loans means that despite highly subsidized interest rates, they currently have a grant element in the range of 30 to 35 percent. [2] [3] At the end 2022, 19 of the 35 LICs in Sub Saharan Africa were already in or at high risk of debt distress and just over half of PRGT credit outstanding was to countries similarly placed. And, on average, this debt amounted to about 3 percent of the borrowing countries’ GDP.[4]

But the PRGT also has a crucial role to play in supporting policies to prevent and resolve debt distress. By helping to catalyze financial support on appropriate terms, well-designed macroeconomic frameworks can help moderate debt vulnerabilities. The PRGT also plays a central role when debt restructuring is required through the Common Framework. As well as serving as the fulcrum for orchestrating debt restructuring – as in the prolonged process to provide debt relief for Zambia – the PRGT can provide essential support alongside this relief to rebuild financial buffers. The experience of debt relief provided by the two rounds of The Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative is illustrative. In the first round, debt relief essentially removed obligations that would not be repaid and as such did not provide any new fiscal space. It was only in the second round that debt relief provided fiscal space for, inter alia, essential social spending. While the Common Framework ostensibly aims for the latter - with debt relief yielding fiscal space – at this early stage it is not clear that the outcome will always be so. At the margin, a more restrictive outcome will add to demands in the PRGT. Delays in reaching an agreement on debt restructuring are also likely to add to pressures on the recipient country and thus the demand for PRGT financing.

Concessionality could be increased by lengthening the maturity of PRGT loans. There would however be trade-offs in terms of subsidy costs and program engagement. If the annual lending envelope were to remain unchanged with maturity doubled (from 10 to 20 years) the stock of PRGT credit and subsidy costs would also broadly double. At the other extreme, if subsidy costs were to be the same as for the PRGT with a 10-year maturity, annual lending commitments would need to be halved. This would in turn either reduce the size or frequency of PRGT arrangements. In view of the constraints on subsidy resources, lengthening maturities would probably see an outcome closer to this second possibility. Given the greater vulnerability of LICs to shocks, it is not clear that longer maturities at the costs of more limited disbursements when needs arise would be beneficial.

But how large should the PRGT be?

There is no simple metric to determine how large the PRGT should be. Given the scale of LICs addition financing needs – estimated at about US$440 billion during 2022-26[5] – the PRGT’s contribution to this overall financing must continue to be largely catalytic. But to be able to continue to play a key role in supporting macroeconomic stabilization in LICs, the PRGT must have sufficient resources to be able to contribute in a meaningful way to a country’s immediate financing needs. The lack of adequate resources to be able to meet this need on a sustained basis was evident earlier this year when the IMF increased access levels for its non-concessional lending but delayed a decision on access levels for the PRGT.[6]

Over the next 5 to 10 years an important factor affecting LIC’s financing needs will be the scale of their repayments to the PRGT. In the decade before the pandemic, repayments to the PRGT averaged about 1 billion SDRs a year. (Disbursements were on average slightly higher so that the stock of PRGT credit gradually increased to SDR 6.6 billion in 2019). In contrast, because of the sustained high levels of lending since 2020, repayments to the PRGT will begin to rise sharply over the next two years and will reach over SDR 3 billion a year in the early 2030s. The demands on the PRGT will therefore depend in part on whether countries are able to meet these repayments without higher external support or whether they will need to “roll over” their PRGT loans.

Given repayment schedules, a lending capacity of SDR 1.65 billion a year would imply a large, sustained withdrawal of PRGT credit. The IMF’s updated projections, which underpinned the increase in estimated financing for the period 2020-24, imply that the stock of PRGT credit will rise to over SDR 27 billion. If PRGT lending then averaged SDR 1.65 billion a year, repayments would exceed disbursements by an average of almost SDR 1.4 billion a year and the stock of credit would halve within a decade to about SDR 13 billion.[7] This withdrawal of PRGT credit would be equivalent to about 90 percent of the SDR allocation that LICs received in August 2021. And this net repayment would start when LICs’ financial buffers have not recovered from recent shocks. For example, despite the SDR allocation and high levels of PRGT support – both of which, in the first instance, added to the countries’ gross reserves – the average reserve cover of LICs in Sub-Saharan Africa declined from 3 months of imports 2019 to 2 months in 2022 and is not projected to recover in the next two years.[8] For some PRGT borrowers, financial buffers will be further stressed by the high levels of sovereign bond repayments falling due in the next two years.[9]

A larger capacity would be needed to limit the decline in total PRGT credit. Some countries, particularly those that only received emergency financing under the PRGT’s RCF in 2020-21, and whose economies were stronger than most LICs before the pandemic, may be able to repay without further support. If, for example, all the current RFC credit outstanding was repaid without further support, but other borrowers required continued PRGT support, the resulting reduction in credit would be broadly consistent with an annual lending capacity of SDR 2.65 billion. However, some countries that drew on the RCF are already transitioning to more typical financial and policy support with three- year arrangements under the PRGT’s Extended Credit Facility. If only half of the outstanding RCA credit were repaid without further support, this would bring a decline in credit broadly in line with an annual lending capacity of SDR 3 billion. The IMF’s own projections of long-term demand in it April assessment of PRGT finances were also in the range of SDR 2.65 to SDR 3.0 billion a year.

Funding options

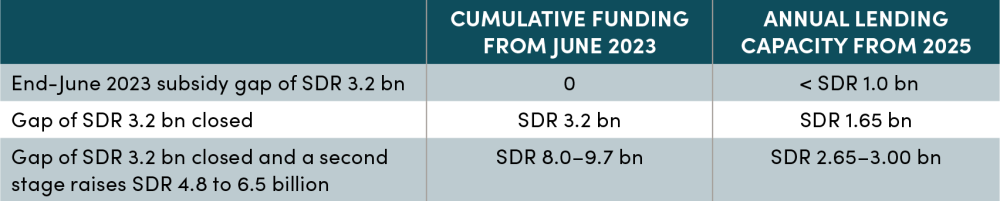

The IMF will soon begin to consider options for a medium-term strategy to restore the sustainability of the PRGT.[10] As of late June, a further injection of SDR 3.2 billion would be required to achieve a self-sustained lending capacity of SDR 1.65 billion from 2025 onwards. Raising this capacity to a range of SDR 2.65 to SDR 3 billion would require an additional SDR 4.8 to 6.5 billion, bringing the total financing need to SDR 8.0 to SDR 9.7 billion. For simplicity, the higher estimate of the total cost – SDR 9.7 billion -- will be used in assessing options.

Table 1. Subsidy needs and the lending capacity of the PRGT

This medium-term strategy is to be ‘burden-shared’. This is IMF terminology that means the costs should be borne across the membership as well as through the possible use of the IMF’s own ‘internal’ resources. On the latter, the IMF’s most recent assessment of PRGT resources noted that ‘the use of internal resources will play a key role in laying the foundations for the longer-term sustainability of the PRGT.

Changes to elements of the PRGT’s financial architecture could also be in the mix of options. The estimates of the financing need given above assumed no such changes to PRGT policies. For example, they include the cost of resuming reimbursement of the GRA for the annual administrative costs of running the PRGT after the suspension for the years 2020-24 and there is no change in the mechanism for setting the interest paid by PRGT borrowers, or the interest rate paid by countries lending the PRGT.[11]

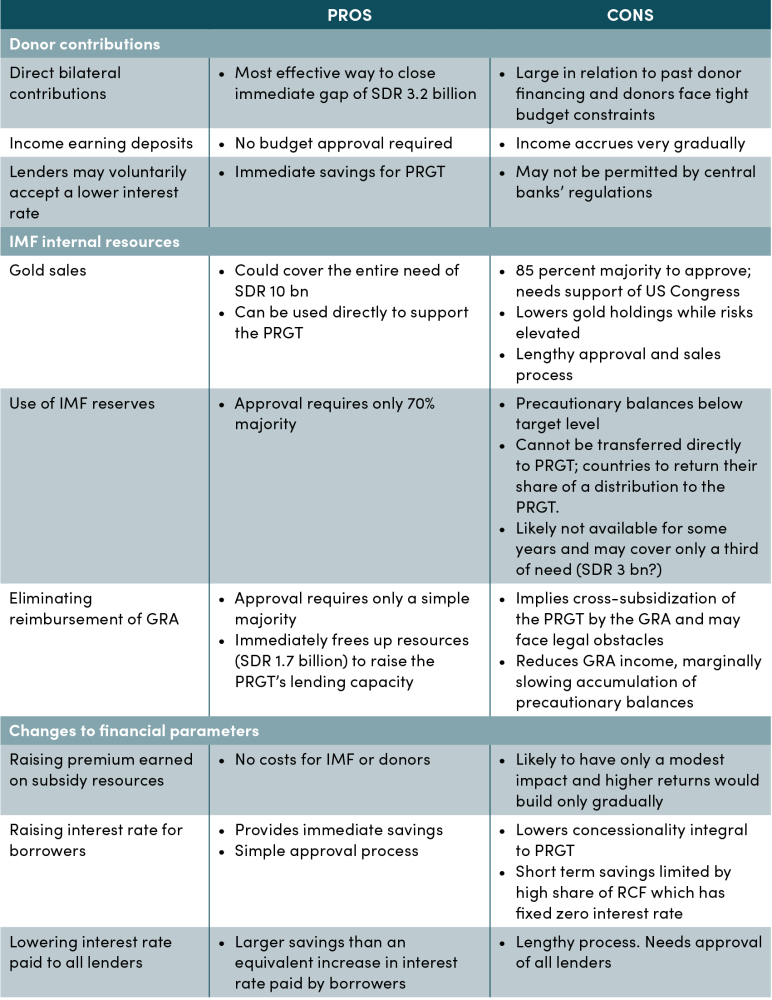

Table 2. Pros and cons of PRGT funding options

Donor contributions with different modalities

Donor contributions are the most effective vehicle for closing the immediate financing gap of SDR 3.2 billion. Provided fund-raising is reasonably synchronized with countries’ budgetary cycles, decisions on donor support could in principle be made much more rapidly than on gold sales or the use of IMF reserves (discussed below). For the most part there is also no need for this donor support to be delivered rapidly in cash terms; there is no cash shortage of resources to meet immediate subsidy needs. Firm commitments to deliver budgetary support in future would typically suffice, alleviating looming constraints on the capacity to commit new PRGT lending and related subsidy resources.

The PRGT’s large financing need comes as donors face tight budget constraints. The 2021 target of SDR 2.3 billion for donor contributions was also large in relation to past fund-raising. Since the inception of the PRGT and its predecessors in 1987, subsidy contributions from member countries to support for the IMF’s concessional lending have totaled SDR 5.5 billion, but about SDR 2.2 billion of this amount was in effect funded by a distribution of profits from gold sales (as discussed below). Against this background, and the severe budget constraints facing countries, the fund-raising effort was broad based, targeting 61 countries who together account for close to 90 percent of IMF quotas; the ask of each country was linked to its quota share in this group of countries.

Fund-raising got off to a slow start; at end-June 2023 there was still a shortfall of SDR 0.9 billion from the initial target of SDR 2.3 billion. Most of the countries that have pledged so far have met or come close to the ask made of them. The most important exception is the US which has not made large contributions in the past (except for returning profits from gold sales) and has pledged only an eighth of an ask of SDR 456 million and accounts for over 40 percent of the total shortfall. But since some countries (and the EU) have provided more than asked and more than half of the 61 counties have yet to make a pledge, it is reasonable expect the shortfall to narrow. But that would still leave the additional amount of SDR 2.3 billion unfunded, so that most of the immediate financing gap of SDR 3.2 million would remain.

In addition to direct budgetary commitments, there are other modalities for support that the IMF has encouraged. Subsidies can be provided by lenders agreeing to receive less than the SDR interest rate on their loans to the PRGT. However, only the UK is providing loans to the PRGT at less than the SDR interest rate, in this case at 0.05 percent. (The recent rise in the SDR interest rate raised the implicit subsidy provided by these loans, so that it is estimated to be more than double the subsidy contribution sought from the UK). Most of the other 17 countries that currently lend to the PRGT have also pledged subsidies in the form of (budgetary) grants. This may reflect constraints on their central banks’ ability to place reserves at below market rates or simply a preference of use budgetary funding. But as my colleagues Mark Plant and Andrew Ghattas have noted in a recent blog, this could be a relatively quick and easy way for lenders to provide support to the PRGT. As such, as discussed later, it could be a useful plank in building a sustainable PRGT for the long-term.

Contributions can also be made by placing SDR or hard currencies deposits with the PRGT that are invested to generate subsidy resources. So far use of this modality has been limited, even though it is in principle available to all potential contributors and not just the 18 countries that provide the resources that the PRGT on-lends. If contributors opt to be paid the SDR interest rate on their deposits, the net returns of the Deposit Investment Accounts (DIA) will be limited to the premium it can earn of the SDR interest rate. Over the longer term, this is expected to be about 0.5 percent; a deposit of SDR 10 billion, paying the SDR interest rate to the depositor, could in principle earn up to SDR 50 million a year for the PRGT and, with cumulative interest, about SDR 0.5 billion over 9 years. But the premium cannot be generated while the yield curve remains inverted. The yield for the PRGT can be significantly increased if the depositor agrees a receive less that the SDR interest rate.[12]

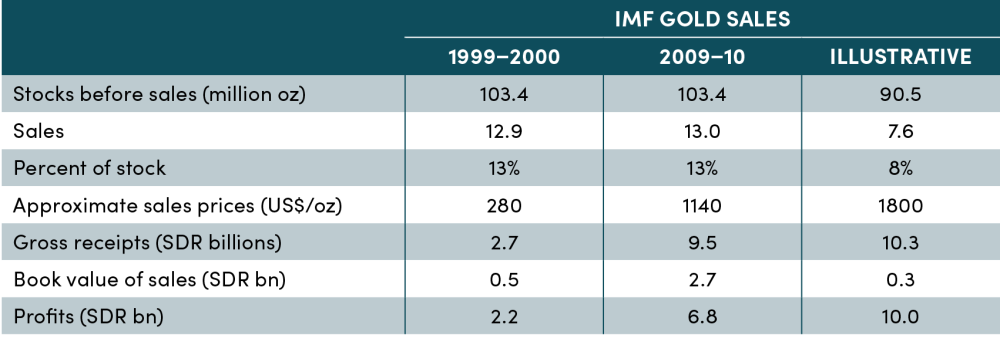

Gold sales: a panacea or a tantalizing prospect?

Sales of IMF gold could, in principle, meet the entire financing needs of the PRGT. The IMF’s gold holdings have a book value of about SDR 3 billion, but their market value is currently over $176 billion (SDR 131 billion). Even assuming the gold price retreats from its current high of close to $2,000 per oz to $1,800 per oz, selling just 8 percent of the IMF’s gold would yield profits over the book value of about SDR 10 billion. These profits could in effect be placed directly in the PRGT’s reserve to bolster subsidization capacity. And this would not be breaking new ground; the reserve account which now stands at about SDR 4 billion has been largely funded by past gold sales.

But there are very significant obstacles to gold sales. Since gold sales require the support of 85 percent of the IMF’s Executive Board, they cannot proceed without US support and, crucially, the US administration cannot support gold sales without congressional backing. In the last 25 years there have been only two rounds of gold sales. Both required a complicated and lengthy approval process, and executing the sales was also very time consuming.[13]

Assuaging concerns that IMF sales could disrupt the gold market was an important factor in gaining support for these two rounds of gold sales. In 1999-2000 market disruption was avoided by the unusual expedient of off-market sales to two countries who then used the gold (at the same market value) to make large repayments falling due to the IMF. In this manner, there was ultimately no change in the IMF’s net gold holdings that could disrupt the market. Sales in 2009-10 were accommodated within the sales envelope of the Central Bank Gold Agreement between the ECB and 21 other central banks. Just over half the sales were direct sales to central banks and market sales were phased over an extended period, further limiting any potential market impact. In present circumstances there should be less concern over market disruption. The proposed volume of sales (to raise SDR 10 billion) would be significantly smaller than in 1999-2000 and 2009-10 and equal to under 3 percent of global gold production. More importantly central banks have in recent years been large buyers of gold; in 2022 alone central bank net purchases were equal to about 40 percent of the IMF’s net gold holdings.[14] A continuation of this pattern of net central bank buying should lessen any concerns over market disruption, with little or no need for direct market sales by the IMF.

Table 3. IMF gold sales, 1999-2000 and 2009-2010

Source: IMF and author's estimates

The IMF’s gold holdings are also seen as providing fundamental strength to its balance sheet. When the IMF lends its GRA resources to countries in distress, it draws upon the quota and loan resources of the typically 60 or so member countries considered to have sufficiently strong external positions. The central banks providing these resources can carry these loans at full face value on their balance sheets because the IMF in turn carries the credit risk in intermediating these resources and, in this context, the IMF’s gold holdings serve as the ultimate backstop to the IMF’s unique financing mechanism.

Concerns over weakening this backstop against credit risk were not a prime consideration in the approval of the last round of gold sales, as IMF credit outstanding was not high. Earlier sales were approved against the backdrop of historically low levels of IMF lending, just before the global financial crisis. Although higher-than-expected profits were used indirectly to support the PRGT, the primary motivation for the sales was to fund an endowment (as part of the IMF’s New Income Model) to provide a durable source of income to help meet IMF’s operating costs, absent significant on-balance-sheet lending.

IMF credit outstanding is now at record highs but there is a case to be made that gold sales would not significantly impact the fundamental strength of the balance sheet. There is no clear-cut metric to determine what level of gold holdings is adequate and there is always likely to be a strong element of judgement in making such an assessment. But what is clear is that while IMF credit has risen to close to SDR 100 billion, the value of IMF gold holdings is also at a record high and has risen by considerably more than IMF credit. As a result, the value of IMF gold holdings is also higher relative to the stock of credit than during past peak levels of lending. Moreover, if the IMF were to sell as much as 8 percent of its gold, and gold prices fell back to 1800 per oz, the value of its gold holding would still be higher is relation the level of lending than at past peak periods. Using a different metric, the value of IMF gold is also now higher in relation to the GRA’s total lending capacity of about US$1 trillion than it has ever been. However, there still likely be some concerns among major IMF shareholders that gold sales would lower financial buffers when borrowing risks are elevated (as discussed below). [15]

Figure 2. GRA credit outstanding and the market value of the IMF's gold, in billions of SDRs

A concerted effort will be needed to unlock gold sales. The technical arguments against sales – concerns over possible market disruption and the need to main the fundamental strength of the IMF balance sheet – should not be insurmountable. The primary challenge is likely to be gaining US congressional support. The task is more difficult now that an assertive minority is openly opposed to multilateralism. But against this, it is important to stress that gold sales would not have any budgetary costs for the US. From a different perspective, longstanding concerns that IMF financial support could amount to public bailouts of other creditors would need to be assuaged drawing, for example, on the successful application the G20 Common Framework in Zambia’s PRGT-supported program. While the potential gain from gold sales is clear, given large uncertainty over approval of gold sales, alternatives are also needed.

The IMF’s reserves could also bolster the PRGT’s finances.

Some of the IMF’s (non-gold) reserves on its main balance sheet could be used to support the PRGT. These reserves – precautionary balances in the IMF’s terminology – have increased by more than SDR 10 billion in the last 10 years to about SDR 22.6 billion[16]. And the approval threshold for a distribution of reserves is, on the face it, less demanding than for gold sales, requiring a 70 percent majority in the Executive Board. But there are significant technical and policy obstacles that are likely to at least limit the scale of any reserve use in the near term.

The IMF’s reserves also provide an important buffer to mitigate credit risks. Although they are much smaller that gold holdings, they are readily available on the balance sheet at thus provide a more immediate line of defense. The last review of the adequacy of precautionary balances in December 2022 maintained a target of SDR 25 billion for these reserves, with the expectation that this would be reached in two years.[17] At the time it was recognized that credit risks had risen and were heightened by a peak in repayments to the IMF (totaling SDR 35 billion) in the next two years. Against this background, it may be difficult to justify a decision to use reserves, at least in the next two years. Thereafter, depending on how risks evolve, there may be greater scope to use reserves. But IMF shareholders would need to be confident that any use of reserves would leave an adequate buffer against credit risks for future periods of high lending.

The debate over the IMF’s surcharge policy could also complicate approval for the use of reserves. Surcharges are the higher interest rates that apply when a country’s borrowing the IMF reaches higher levels.[18] Their purpose is to mitigate risks by providing incentives to avoid large and prolonged use of IMF resources and by contributing to reserve accumulation. In the last 10 years surcharge income has amounted to about half of the IMF’s total income from non-concessional lending. But the effectiveness of surcharge policy – and from the borrowers’ perspective, its equity – has come under greater scrutiny, especially as borrowing countries faced the additional challenges of the pandemic. The heavy concentration of surcharges on the largest borrowers has added to this scrutiny; in the last 10 years, the IMF’s five largest borrowers have consistently accounted for over 90 percent of total surcharges paid to the IMF.[19] The last review of precautionary balances illustrated the possible impact on reserve accumulation of providing some temporary relief from surcharges, but there was no consensus on how to move forward. The aim here is not to opine on the surcharge policy per se, but rather to note the additional complication that it creates for a decision on the use of reserves. Any relief from surcharges would slow reserve accumulation, and likely make it harder to decide to use reserves to support the PRGT. Conversely, going ahead with a distribution could be seen as undermining one of the principal arguments against surcharge relief, namely that it would delay the attainment of the reserve target of SDR 25 billion.

Reserves cannot be transferred directly to the PRGT. The IMF’s Articles of Agreement constrain the use of reserves. By a 70 percent vote, some portion of reserves can be distributed to member countries, pro-rata to their quota shares in the institution. But the Articles do not allow for direct transfers to entities such as a the PRGT. Instead, a distribution could be made in the expectation that recipients return their shares or agree that they go directly to the PRGT. To minimize ‘leakage’, a decision to go ahead with a distribution could be made conditional on a high level of commitments from member countries to return their shares of the distribution. This approach was taken following the gold sales in 2009-2010. Two distributions of profits were made in 2012 and 2013 after the IMF received assurances that 90 percent would be made available for the PRGT.[20]

This time around the non-transfer of reserves could be higher. The reserves to be distributed were generated essentially from the IMF’s lending income (rather than profits from gold sales) and thus reflect earlier interest payments, including surcharges, paid by borrowers. These borrowers might want to recapture the payments they made. To give some sense of possible magnitude of this effect, the five largest borrowers who now pay the bulk of surcharges would receive about 2 percent of this distribution as would the three large borrowers in the euro area crisis and countries who currently have outstanding non-concessional credit have a combined quota share of about 7 percent. Of course, we cannot know whether borrowers would ultimately agree not to retain their share of any distribution but the process of obtaining the required assurances is likely to be protracted. It took over a year to obtain the requisite assurances for the second profits distribution for the PRGT in 2013. This cumbersome process required to move reserves to the PRGT has another awkward feature that may complicate any decision to go ahead. Since the distribution must be made according to quota shares, there may be no way to prevent all countries, including Russia, from benefitting. [21]

In sum, these complexities are likely to delay and limit any the use of reserves. A decision on a distribution would be difficult while risks remain elevated and the precautionary balance target has not been attained. Thereafter there may be greater scope, but any use of reserves would likely be much smaller than the scale of resources that could be attained from gold sales. There are many uncertainties but a figure in the range of SDR 3 billion may be the upper limit given the need to ensure that precautionary balances are adequate to address future risks. As noted, there may also be a significant loss with not all of this going to the PRGT. Even if a decision on a distribution can be taken in two-year’s time, it may take at another year or so to have the required assurances to go ahead. So, like gold sales, use of reserves would not provide a means to cover immediate financing needs.

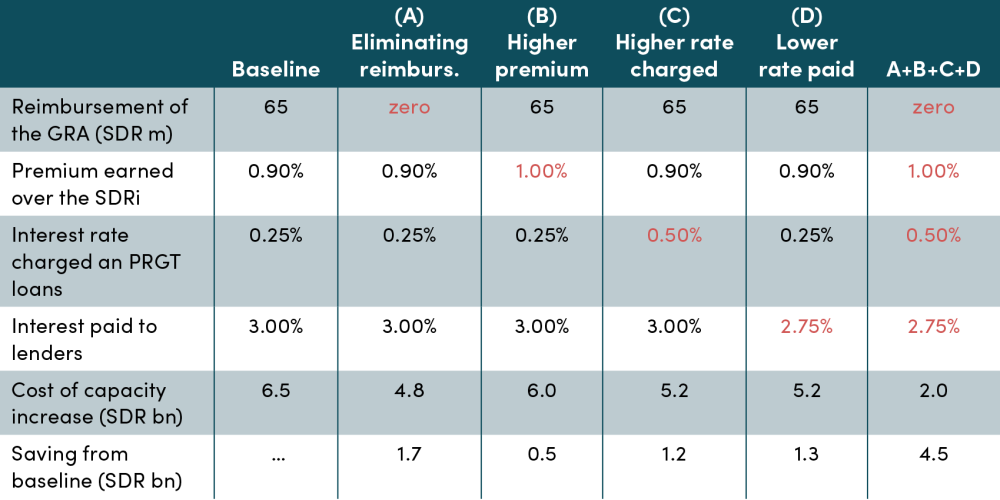

Costs could be lowered by ending reimbursement of the GRA

The IMF could make a large contribution to the PRGT by permanently ending reimbursement of the GRA. As noted earlier, annual payments that the PRGT makes to the GRA to cover the administrative costs of running the PRGT were suspended for 5 years as part of the fund-raising effort launched in July 2021. The estimated savings for the PRGT represented a contribution of IMF internal resources of SDR 500 million. But the cost estimates for a resumption of the self-sustained PRGT in 2025 assume that reimbursements also resume. This would place a significant burden on the PRGT. The average annual cost of reimbursement is assumed to be SDR 65 million. At an average SDR interest rate of 3 percent this implies that SDR 1.7 billion of the PRGT’s endowment is in effect dedicated to generating income to cover the annual reimbursement cost rather than meeting subsidy costs.[22] If this part of the endowment was instead used to cover subsidies, this would raise the sustainable lending capacity by about SDR 0.35 billion. Thus, if the subsidy gap of SDR 3.2 billion were closed this would, without reimbursement, yield a lending capacity of SDR 2 billion rather than SDR 1.65 billion with reimbursement. In practice, the impact of ending reimbursement could be significantly larger than assumed here. The annual cost of reimbursement is likely to be higher than SDR 65 million, particularly if a larger PRGT is needed to meet the needs of LICs. In this vein, it is notable that annual savings (plus a small amount of accrued interest on these savings) from suspending reimbursement during the current period of high lending were estimated be the IMF at SDR 100 million a year.

Eliminating reimbursement would break with one of the principles underlying the IMF’s New Income Model. As noted above gold sales in 2009-2010 were primarily aimed at establishing an endowment to provide a sustainable source of income for the IMF’s administrative budget. At the same time this New Income Model drew a distinction between IMF activities, such a surveillance, considered to be public goods and lending activities that principally benefitted recipient countries. Drawing upon this distinction, the PRGT was to reimburse the GRA for the administrative costs of lending operations – avoiding cross subsidization by the GRA. Similarly, countries borrowing for the GRA are charged a margin to meet operating costs. In contrast, no charges were levied on public goods provided to member countries. In the years since this new income model was introduced, the IMF’s budget outlook has changed dramatically. Persistently high levels of lending income have allowed reserves to accumulate; reimbursement is now a relatively minor income source and one that is unlikely to be needed to support the budget over the long term. From a policy perspective there are also good grounds to question the distinction between public good and other IMF activities used in the new income model. The pandemic clearly illustrated the public good aspects of PRGT lending and, even in more normal circumstances, the PRGT’s sustained support for macroeconomic policies in LICs to foster growth and poverty reduction can be seen as providing a global benefit.

Although the best option would be to eliminate reimbursement, a prolonged suspension could provide important support. Eliminating reimbursement would remove the future stream of reimbursement obligations which would otherwise be funded by income from about SDR 1.7 billion of the endowment’s assets. If elimination is not possible the temporary relief could be extended.[23] The IMF’s most recent assessment noted that 10-year suspension could save about SDR 0.8 billion. And these savings would accrue to the reserve account which has fallen sharply as a percent of total credit outstanding.

And changes could be made to other key parameters of the financing model

Other changes to the PRGT’s financing architecture could also lower the financing need. The endowment’s current investment strategy is geared to earning a premium of 90 basis points over the SDR rate. There may be scope for raising this premium over the longer term by, for example, increasing the proportion held in equities from the roughly 20 percent reported in April 2022.[24] However, the potential savings from incremental changes to this strategy are likely to be relatively modest. Raising the premium by 10 bps to 1.0 percent would lower the cost of raising future capacity from SRR 1.65 to SDR 3 billion by about SDR 0.5 billion

Charging borrowers a higher interest rate would lower costs but decrease the concessionality of PRGT loans. The current estimates assume that when self-sustained lending resumes, borrowers pay interest rates as established under the PRGT’s interest rate mechanism. By design, emergency borrowing under the PRGT’s RCF is always interest free. At the assumed SDR interest rate of 3 percent, PRGT borrowers would pay an interest rate of 0.25 percent on their non-RCF borrowing and this rate would not rise to 0.5 percent unless the SDR rate itself reached 5 percent. In present circumstances, the savings for the PRGT of raising the interest rate are limited because the RCF credit accounts for an unusually high share – almost half – of the total. Over the longer term, assuming RCF lending reverts to being a very small share of total PRGT credit, raising the rate by 0.25 percent would lower the cost of raising future capacity from SDR 1.65 to SDR 3 billion by about SDR 1.2 billion. But there is a very important drawback. Higher rates would lower the concessionality of PRGT lending at a time when an increasing number of LICs are at risk of debt distress.

Paying all lenders a lower interest rate would lower costs. The savings would be similar to the savings from charging lenders a high rate.[25] Paying lenders 0.25 percent less than the SDR interest rate would lower the cost of raising future capacity from SDR 1.65 to SDR 3.0 billion by about SDR 1.3 billion. Combining these four changes – eliminating reimbursement (which by itself lowers the cost by SDR 1.7 billion), raising the premium earned by the endowment, charging a higher rate to borrowers and paying a lower rate to lenders -- would reduce to about SDR 1.9 billion the cost of raising capacity from SDR 1.65 billion to SDR 3.0 billion .[26]

Table 4. Estimated costs of raising the self-sustained capacity from SDR 1.65 billion to SDR 3.0 billion

Source: Author's estimates

Bridging the gap

A concerted effort is needed to push for the approval of gold sales. Relatively modest gold sales could meet the PRGT’s current financing needs and sharply raise its lending capacity for the future. This could be achieved without raising the costs to borrowers or lowering the rate of interest paid to lenders. If desired, the costs of resuming reimbursement of the PRGT could also be covered. None of the other options – either individually or in combination - can deliver quite the same outcome.

But gold sales cannot be the only option. Given the uncertain prospects for approval, other avenues including use of reserves should be developed alongside the push for gold sales. Even if gold sales are eventually approved, the resulting gold profits would probably not be available for the endowment in the next three years. This delay is likely to increase costs. The current financing envelope, with a shortfall of SDR 3.2 billion, would leave the PRGT with a sustainable lending capacity of less than SDR 1 billion from 2025 onwards. Only when gold profits are mobilized would the capacity rise to SDR 3 billion. In the interim, maintaining lending capacity at SDR 3 billion would entail a commitment of additional subsidy costs of about SDR 0.5 billion a year. These could in principle again be covered by committing resources from the subsidy account. But the scope to do this is now limited; further resources are urgently needed.

A plan to use IMF reserves would need to embrace other options. A decision to use reserves is not subject to the same political uncertainties that could block gold sales. But the contribution that reserves could make is much more limited given the need to ensure that the IMF has an adequate buffer to deal with future risks on its balance sheet. Like gold sales, any mobilization of reserves for the PRGT is also probably at least two years away. Additional resources would be needed to cover the period before reserves can be used and to augment the contribution that reserves can make. Without any other actions, the use of reserves would probably cover less than a third of the total financing needed (of SDR 9.7 billion) to replenish the PRGT and leave it with a capacity of SDR 3 billion a year. Eliminating reimbursement would narrow the gap but still leave a shortfall of about SDR 5 billion. Large scale donor financing would then be needed to close the gap; without this, either the subsidy provided to borrowers would need to be reduced or PRGT operations scaled back from the target level of SDR 3 billion per annum.

Without gold sales or the use of reserves the PRGT would be further constrained. Donor contributions are urgently needed. Under any of the options, a prompt injection of subsidy resources is needed now to now buy time, supporting lending until a longer-term solution is in place. But if gold sales and use of reserves are both ruled out, the outlook becomes much more difficult. All the changes set out in the table above would need to be considered to bolster capacity, or the PRGT’s operations would need to be scaled back.

An alternative to the existing model should be considered

The sheer scale of the financial challenges facing the PRGT begs the question of whether a different financial model is needed. In the best case, the financing gaps will be closed and PRGT’s lending capacity will be suitably augmented. But the prospects for achieving this desirable outcome are not encouraging. There is a very real risk that gold sales do not materialize. And the alternative of some use of reserves and donor finance may not provide adequate resources. The circle is then likely to be squared by some combination of tight credit rationing and lower concessionality for PRGT loans. The resulting scaled-back PRGT would be less attractive to borrowers and less effective in supporting the macroeconomic stability that is essential for sustaining growth and reducing poverty. Since this is an outcome which all would want to avoid, it seems wise to look seriously at alternatives to the current model. We begin by looking at what the existing model does and does not provide.

The pros and cons of the existing model

The PRGT has evolved into a key vehicle for the IMF’s support for LICs. It provides financing on terms that are better geared to the needs of LICs than are those of the GRA. Operating as a trust also provides greater flexibility in the IMF’s support for LICs. In particular, the lending operations of the GRA are limited to meeting the type of balance of payments needs defined in the Article of Agreement. This does not square with the protracted balance needs of LICs that the PRGT addresses.

The PRGT’s existing financial model allows subsidy needs to be met with complete certainty, without need to seek additional resources if commitments stay within the self-sustained capacity. The model is also able to meet subsidy costs even if interest rates rise very sharply. As currently structured if commitments on average stay within the self-sustaining capacity, the stock of debt outstanding can only exceed the size of the endowment by a small margin.[27] This means that sharp increases in the SDR interest paid to countries lending to the PRGT are matched a corresponding increase in the earnings of the endowment. The large reserves in the endowment also provide a very strong assurance to lenders that they can be repaid even if borrowers are unable to repay the PRGT.

But the existing model it is not resilient to very large and sustained surges in lending. The lending capacity of the PRGT model is not a fixed annual limit; temporary periods of higher demand can be met if matched by subsequent lower demand. But if demand surges and stays high for a sustained period, the self-sustaining model must be set aside. In this way, the large resources of the endowment provided a buffer to support unsustainably high levels of subsidized lending during COVID and its aftermath. But as is all too evident now, restoring the endowment to allow sustainable lending to resume is a very costly endeavor. In a global environment that is now characterized by multiple crises, is it wise to rely on a financing model for the PRGT that is itself not resilient to large and sustained increases in demand?

Equipping the existing model with an adequate buffer to enable it to weather extreme events would add greatly to the costs. As is clear from the earlier discussion, it is not realistic to expect the PRGT to hold such a large buffer. Indeed, looking at the PRGT in the context of the operations of other IFIs, some question whether a large endowment funded in part by member country budgetary contributions is the best use of public resources. And this issue has been brought into sharper relief by the pressure on MDBs to leverage their capital more efficiently to support higher levels of lending.

The existing model’s reliance on voluntary support is out of step with the importance of the IMF’s support for LICs. The resources lent to LICs by the PRGT are provided under voluntary borrowing agreements, typically with fewer than 20 countries. These lenders also provided the bulk of subsidy resources for the PRGT before it became self-sustaining and have been large contributors in latest round of fund-raising. In contrast, the financial operations of the GRA are buttressed by obligations on the membership to provide resources that are enshrined in the IMF’s Articles of Agreement and related decisions. This difference in the nature of the IMF’s concessional and non-concessional operations seems at odds with both the importance of the IMF’s support for LICs and the public good aspects of this support.

Key elements of a possible alternative funding structure

The objective is to try to improve the model in areas where it has fallen short, while retaining elements that work well. Given the PRGT’s recent experience and current financing needs, the alternative set out below is primarily geared to making the PRGT’s financing model more resilient to shocks and lowering the costs of equipping the PRGT to operate with a larger sustainable lending capacity. But these costs should not be lowered by moving away from the current structure of subsidized interest rates that is an integral feature of PRGT support.

Any improvement on the current model is likely to entail trade-offs. A smaller endowment would lower the costs of returning the PRGT to sustainability. But if a smaller endowment is bearing less of the costs and the costs are not passed on to borrowing countries, then the burden must fall elsewhere. In the alternative sketched out below, the burden would fall mainly on richer countries including those lending to the PRGT. However, this should be attenuated overtime by greater burden sharing across member countries.

The PRGT would still operate as a trust and retain much of the current financial structure. For the reasons set out above, it would remain separate from the IMF main balance sheet. It would not lend quota resources; loan resources would still be provided through agreements with the membership. And an endowment would still be used to subsidize loans to LICs. There would, however, be important changes.

The endowment would cover some but not all subsidy costs. The smaller endowment would still include a reserve that, as under the current structure, helps to mitigate credit risks for lenders. However, unlike the current endowment, in this alternative structure a smaller endowment would not necessarily cover all subsidy costs. One possibility would be that the endowment meet subsidy costs up to a certain level. This could be structured so that in normal or more benign periods all or most of the subsidy costs would be met by the endowment, but when demand for lending surges, or interest rates reach higher levels, there could be a cap on the interest rate paid to lenders.

There would need to be many more lenders to the PRGT. Instead of relying on ad hoc agreements with a small number of countries, loan resources should ideally be provided by a much larger part of the membership. When countries borrow from the GRA, quota resources are provided by 60 or so member countries with stronger balance of payments positions. Providing these resources is an obligation of membership. Since lending to the PRGT would still be voluntary, somewhat lower participation should be expected. The New Arrangements to Borrow (NAB) serves as a useful model for the PRGT. If quota resources are stretched, loan resources under the NAB come into play. In this way, during periods of heavy demand for non-concessional lending this standing arrangement can be activated to supplement the IMF’s quota resources. Participation in the NAB is not an obligation but it has 39 participants who together account for 80 percent of IMF quotas. In contrast, the 18 countries that lend to the PRGT account for just under half of IMF quotas. Over time, broader participation in this enlarged structure could engender a sense that support for the PRGT is essentially an obligation of IMF membership, albeit one this is not formally required.

An NAB-like structure could also help to ensure that loan resources are adequate. The size of the NAB is periodically increased. A similar approach for PRGT loans, with a larger buffer in the total lending envelope agreed with lenders would avoid the need for ad hoc requests for new loan borrowing agreements as occurred during COVID. It would also be opportune to move to what are effectively revolving credit lines, replacing the borrowing agreements in the PRGT which allow funds to be lent only once.

Lenders in this NAB-like structure would meet part of the subsidy costs for the PRGT by accepting a lower interest rate on their loans to the PRGT. However, unlike the present PRGT, in which there are relatively few lenders, in this alternative structure, the larger number of lenders would imply that the costs of subsidizing loans would be born or burden-shared more equitably across the membership. Countries accounting for 80 percent of total IMF quotas would share in covering part of the subsidy costs.

Broader burden-sharing in this alternative model should include the IMF. Lenders to the PRGT would, as noted above, be called upon to bear part of the subsidy costs of the PRGT. These costs could be lessened by ending reimbursement of the GRA for the annual administrative costs of the PRGT. Moreover, in this model reimbursement of the GRA no longer appears appropriate when lenders to the PRGT would implicitly be meeting part of this reimbursement cost.

Reaching agreement on how subsidy costs would be shared between the endowment and lenders could be a lengthy process. Numerous iterations might be required to agree on a mechanism under which lenders would be required to bear at least part of the subsidy costs when lending surged or interest rates reached unusually high levels. If some large shareholders were not able to provide loans to the PRGT there would also need to be some mechanism to ensure that they also contributed to subsidy costs during periods of economic stress.

In the first instance the subsidy cost of high levels of lending would likely fall on the central banks of the participating countries. How this is accommodated would depend on domestic constraints and preferences. Some central banks may be able to absorb the costs within their current guidelines or rules governing the investment of their international reserves. For others, the cost might need to be covered by the central government budget either ex ante or in a more ad hoc manner as costs arise. But in all cases broad burden-sharing across a wide swath of the membership should make it much easier for lending countries to absorb these costs.

Moving to this alternative would not be easy, but the reward would be a sustainable PRGT.

In normal circumstances, this alternative model should function much like the existing PRGT. Borrowers would continue to pay zero or very low interest rates and lenders would receive the SDR interest rate or only slightly less with a smaller endowment meeting this difference. During times of stress, this balance would shift with lenders covering a larger share of the subsidy cost. Lenders would be able to assess in advance the likely costs that they would bear. This would preserve the PRGT’s future lending capacity, avoiding the need for a repeat of the current costly replenishment of subsidy resources. The sustainability of the PRGT’s lending would be secured. This should avoid a repeat of recent experience when PRGT lending was self-sustaining… until it wasn’t.

[1] See IMF: PRGT Pledges under the 2021 fundraising round as of June 30, 2023 and IMF MD’s Remarks at the Summit for a New Global Financing Pact, June 22, 2023 which referred to a shortfall of US$1.2 billion.

[2] The grant element is defined as the difference between the nominal (face) value of the loan and the sum of the discounted future debt service payments to be made by the borrower (present value), expressed as a percentage face value. The calculations quoted above use a discount rate of 5 percent.

[3] See the IMF’s 2023 Review of Resource Adequacy of the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust, Resilience and Sustainability Trust, and Debt Relief Trusts, page 48.

[4] See the IMF’s 2023 Review of Resource Adequacy of the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust, Resilience and Sustainability Trust, and Debt Relief Trusts, page 11.

[7] If all commitments were disbursed, the stock of credit would be equal to average annual commitments multiplied by the average maturity of PRGT loans (7.75 years). But assuming 10 percent expire without being disbursed, the stock of credit would be correspondingly lower.

[9] See for example Fitch, African Sovereigns face rise in external debt service payments, December 2022

[11] Under the current mechanism the interest rates charged to PRGT borrowers are reviewed every two years. If the SDR rate averages less than 2 percent in the 12-months before the review, no interest is charged; if the average SDR rate is between 2 and 5 percent, a rate of 0.25 percent is charged; this rate rises to 0.5 percent if the average SDR rate exceeds 5 percent. A regular review that was scheduled for July 2023 would have resulted in an interest in the rate charged to borrowers rising to 0.25 percent. However, this review was deferred pending the comprehensive review of the PRGT and its funding. Raising the interest rate would have had only a minor impact on the PRGT at the time, because an unusually large proportion of the credit outstanding is under the RCF on which no interest is ever charged. All but one of the lenders to the PRGT earn the SDR interest rate on their loans; the UK’s latest loan agreement fixed the rate paid at 0.05 percent – the administrative floor for the SDR interest rate.

[12] The People’s Bank of China receives an interest rate of 0.05 percent on its deposit.

[13] See the author’s earlier paper What’s the Best Way to Bolster the IMF’s Capacity to Lend to Low-Income

[15] The IMF’s gold holdings could also be important if serious consideration were given to IMF borrowing in capital markets. This issue has arisen in the past when quota resources have not been adequate but so far the IMF as relied on borrowing from member countries to augment its resources. In the author’s view, significant commercial borrowing would fundamentally change the IMF’s financial structure, potentially impeding its ability to function effectively as a lender of last resort.

[16] IMF Executive Board Review of the Fund’s Income Position for the financial year ending April 30, 2023

[17] Review of the Adequacy of The Fund’s Precautionary Balances, December 2022.

[18] Surcharges have long been applied to higher levels of lending. The current surcharge policy adopted in 2016 sets a ‘level-based’ surcharge of 2 percent on credit outstanding of more than 187.5 percent of a country’s quota. An additional ‘time-based’ surcharge of 1 percent applies when credit outstanding has been above the threshold for 3 years, or just over 4 years, depending on the type of borrowing arrangement in the GRA.

[20] The gold sold in 2009-10 was acquired after the Second Amendment to the IMF’s Articles of Agreement. As a result the use of profits from these sales was subject to different conditions and the profits could not be transferred directly to the PRGT. Instead, these profits first accrued to the GRA, adding to reserves. A distribution and return process was then used to move the funds to the PRGT.

[21] Russia’s share of a distribution of SDR 10 billion would be about SDR 271 million.

[22] The endowment is assumed to earn a premium over the SDR interest rate of 90 basis points so that SDR 1.66 billion in the endowment would generate an annual return of SDR 65 million.

[23] There could be a legal obstacle to eliminating reimbursement. Article V, section 12(i) of the IMF’s Articles of Agreement requires the GRA to be reimbursed for expenses in administering the so-called Special Disbursement Account which derived from gold sales profits. This has been interpreted to include SDA resources in the PRGT but the reimbursement appears only apply if loan PRGT disbursements are funded with SDA resources which is not currently the case.

[24] See the Notes to concessional lending and debt relief trusts, Audited Financial Statements, April 2022

[25] The lower the rate would be paid to lenders on all PRGT credit, the higher interest charges to borrowers would only apply to non-RFC credit.

[26] The total savings would be slightly less than the sum of the individual parts because all the measures lower the size of the endowment and thus lower savings from the higher premium earned by the endowment.

[27] For example, at a lending capacity of SDR 1.65 billon a year, credit outstanding would peak at about SDR 13 billion, or only about 20 percent higher than the total size of the endowment. But this ratio is not fixed; lowering the interest rate to lenders, raising the interest rate paid by borrowers and eliminating reimbursement would all lower the size of the endowment needed to cover interest subsidies.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.