For nearly 50 years, the world’s “least developed countries” have received extra financial support and preferential trade treatment to help them grow and develop. In the first three decades after the United Nations (UN) created the LDC category in 1971, only one country—diamond-rich Botswana—outgrew that status. Since then, four more countries have graduated, and the pace is set to accelerate over the coming decade. Moreover, the countries approaching graduation in the next decade will pose different adjustment challenges than those that preceded them.

When a country successfully graduates, it loses access to the special finance and trade programs that come with LDC status. In the case of trade, that can mean the graduating country’s exporters suddenly face the higher tariffs that their more advanced competitors face, so-called most-favored nation (MFN) tariffs. Even if these countries remain eligible for the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) that is available to developing countries, those programs are typically much less generous than the duty-free, quota-free market access that most advanced economies provide for LDCs.[1] Moreover, outside the European Union (EU), few countries provide transition measures for graduating LDCs (see Annex A). Nor does there appear to be much planning to prepare for the coming wave of graduations.

The United Kingdom has already committed to provide barrier-free market access for LDCs, similar to the EU’s Everything But Arms (EBA) program.[2] But British policymakers have a unique opportunity to improve on that model as part of post-Brexit trade and development planning, including to address the coming wave of graduations. And if the UK remains in the customs union, it can work with EU policymakers to improve the graduation process as part of the review of the GSP regulation that expires in 2023.

Experience with LDC Graduation to Date

For the first two decades after the UN General Assembly created the LDC category, there was not even a plan for how countries would graduate.[3] Three years after the UN defined the conditions for graduation in 1991, Botswana became the first country to make the leap. After another relatively long lag with no further graduations, the pace picked up in the late 2000s. Four more countries graduated from 2007 to 2017 and five more are scheduled to graduate between 2020 and 2024 (table 1). Of those 10 countries, six are UN-designated “small island developing states” that have passed the criteria for per capita income and human assets. The three other countries that have or will soon graduate are natural resource exporters, like Botswana, with per capita incomes more than twice the graduation threshold (see Annex B for details on the process).

Table 1. Status of LDCs with respect to graduation eligibility

Notes: CDP = Committee for Development Policy (a subsidiary body of ECOSOC); ECOSOC = UN Economic and Social Council

* Cambodia was just below the per capita income threshold at the time of the last triennial review in 2018, but, if recent growth rates continue, is likely to be close to or over it by the next review. At that time, if its score on the human assets index (HAI) is still above the threshold, it could meet the criteria for graduation for the first time in 2021.

** The 2018 triennial review, which used data from 2014-16, showed South Sudan above the per capita income threshold; more recent World Bank data shows it falling well below that level.

In the next tranche of countries eligible for graduation, there are three more small Pacific island states, plus Nepal. These countries have twice passed the required thresholds, but decisions to schedule graduation have been deferred to 2021 because of concerns about continued economic vulnerability. Nepal is also notable among past and potential graduates in being the only one to pass the thresholds for the two indicators of structural handicaps without having reached the low-middle-income threshold. At the 2018 triennial review, three more countries—Bangladesh, Laos, and Myanmar—met the graduation criteria for the first time. If they are still eligible on at least two of the three thresholds again in 2021, they could be scheduled for graduation as early as 2024.

In sum, 12 of the 14 past and currently eligible LDC graduates are either small island states, or mineral resource exporters with per capita incomes well above the graduation threshold. Some of the island states export fish and fish products that face relatively high tariffs in the EU, and Cape Verde sought access to the EU’s GSP+ program to ease the of graduation impact on its apparel exports (Annex A). Overall, however, the withdrawal of trade preferences after graduations does not seem to have created major problems. The next tranche of potential graduates looks quite different, however, and the process will raise thornier questions for preference providers and recipients alike.

The Changing Face of LDC Graduates

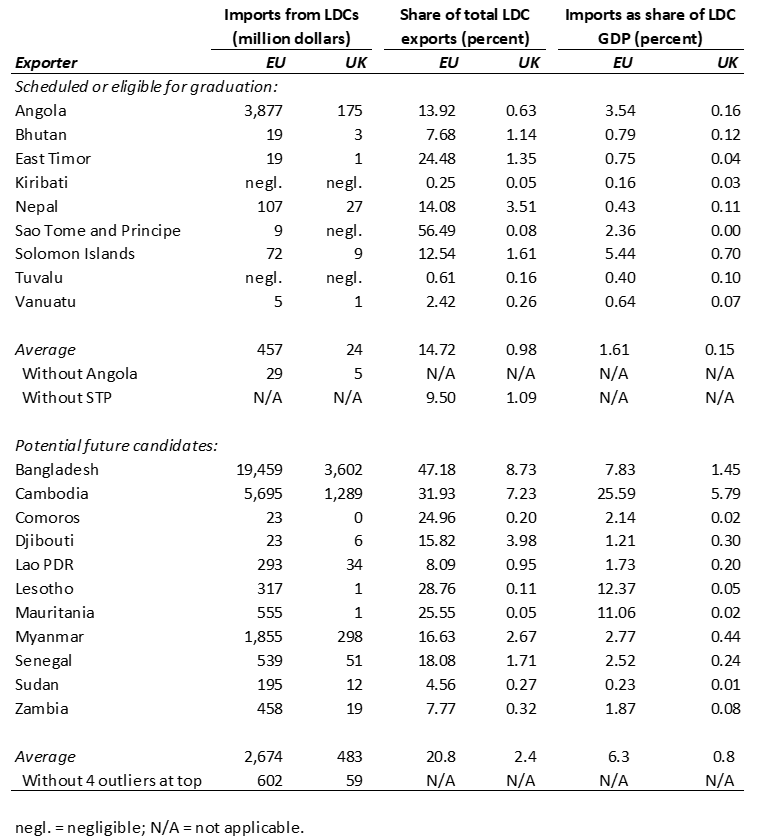

Over the coming decade, potential LDC graduates will be economically larger and more dependent on the European and British markets than the countries that preceded them (table 2). In addition, starting with Nepal, several potential graduates export labor-intensive manufactured goods—apparel, carpets, footwear, and bicycles—that face higher-than-average tariffs, even under the standard GSP program. That makes the trade costs of graduation potentially more severe than for most graduates to date.[4]

Table 2. EU, UK imports from Least Developed Countries (LDCs), average 2016-18

Sources: United Nations Comtrade database; World Bank, World Development indicators.

Upcoming graduates will be larger

Of the countries currently eligible for graduation, Angola is an outlier as a result of its large exports of petroleum, which are mostly MFN duty-free. The other countries in this group are tiny in global trade terms. The average value of total exports for the other eight countries in 2016-18 was under $30 million in the EU and $5 million in the UK (table 2), and just $255 million globally. For the 11 countries that might graduate later in the 2020s, the average value of global exports was $8 billion, with more than a third of that going to the EU and nearly half a billion dollars shipped to the UK (lower part of table 2).

Excluding the two largest (Bangladesh and Cambodia) and two smallest (Comoros and Djibouti) exporters, the average value of exports from this group was still 10-20 times larger than what the current group of pending graduates sends to the EU and UK. This means that the treatment of imports when these countries graduate has larger implications for global trade and for British consumers and importers. Because of the large size of its exports, Bangladesh (at least) would also be ineligible for a more generous GSP+ type program after graduation (see below).

And more dependent on the UK/ EU

Upcoming graduating countries are also relatively more dependent on the EU and UK markets. Of these 11 countries, eight send more than 15 percent of total exports to the EU, compared to just two of the nine currently in the process of graduating (table 2). And one of the latter—Sao Tome and Principe—exports mainly cocoa beans that are MFN duty-free. The UK is, of course, smaller, but it is still important for several of these economies. Overall, the potential future graduates are more than twice as dependent on the EU and British markets as those in the process now (excluding Sao Tome and Principe).

In addition to the past or scheduled graduates that trade relatively little with the EU, there are others like Angola, Botswana, East Timor, Equatorial Guinea, and Sao Tome and Principe, that mainly export products—oil, diamonds, cocoa beans—that are duty-free even without preferences. By contrast, the next tranche of potential graduates includes several that are highly dependent on exports that the EU considers “sensitive” and therefore shields with high tariffs.

Some graduates will face substantial barriers to their major exports

Table 3 shows LDCs potentially approaching graduation that have a nontrivial share of exports going to the EU and UK markets. These include Nepal, which has had the decision on its graduation postponed to at least 2021, as well as Bangladesh, Laos and Myanmar, which could become eligible at that time to graduate three years later. Later in the decade, other countries with a significant share of exports going to the EU and UK could approach graduation, including Cambodia, Djibouti and Senegal.

Table 3 Upcoming LDC graduates: major exports to EU, UK, 2018

(Exports that account for > than half of total exports to these markets)

Note: Includes countries that have met one graduation criterion and send more than 15 percent of total exports to the EU and more than 1 percent to the UK; excludes three small Pacific Island states that have negligible exports to the EU and UK (Kiribati, Tuvalu, Vanuatu).

*Based on this temporary tariff schedule.

Sources: United Nations Comtrade database, online; International Trade Centre, Market Access database, online.

With the exception of Djibouti, this group of potential graduates will face relatively high tariffs on their major exports to the EU—even if they are still eligible for standard GSP benefits. Of the African countries in the table, only Senegal will have to contend with high tariffs and onerous regulations on its fish and agricultural exports. The four Asian LDCs, however, export apparel, footwear, and other labor-intensive manufactures that often face tariffs of 10 percent or more, even under GSP. Moreover, these countries are highly dependent on a relatively narrow range of exports in these high tariff sectors. For Bangladesh and Cambodia, the exports listed in the table account for more than 90 percent of everything they export to the EU and UK. For Laos, Myanmar, and Nepal, the average is around 70 percent, and for Senegal, fish and vegetable products constitute more than half of total exports.

This pattern of trade means that future graduates could see tariffs on their exports jump by several percentage points overnight. Even with careful planning and improvements in competitiveness—which are absolutely necessary—this change would be difficult to overcome, and it would almost surely reduce exports and destroy jobs. In addition to providing aid for trade to address infrastructure and other competitiveness issues, the UK, EU and other preference providers should also use trade measures to ensure a “smooth transition.”

Supporting the Graduation Process in a WTO-Compatible Way

It will not be difficult for British policymakers to do better than their counterparts elsewhere when it comes to crafting a more effective transition process for LDC graduates. Most preference providers have no formal rules for graduation and they either remove preferences immediately, or they extend preferences on an ad hoc basis with little transparency (Annex A). The EU’s EBA program is better in that it provides a three-year transition period systematically to all graduates. But at the end of that period, countries can still face a sudden jump in tariffs.

How the UK approaches these issues depends, of course, on the exact terms of its exit from the EU. In October 2019, the Department of Trade released a temporary tariff schedule that would apply in the case of a no-deal Brexit. That schedule eliminates tariffs on a broad range of products, including bicycles, footwear and carpets that could affect LDC exports (table 3).[5] Yet the government also stated that it was maintaining tariffs on bananas, sugar and certain fish products—and it later added more clothing items—to preserve preference margins for developing countries.[6] It would not be surprising if domestic interests also had some influence on that list.

Assuming that the post-Brexit tariff schedule will maintain some tariff peaks, British policymakers will face the conundrum of what happens to LDC exports of those high tariff products when they graduate. One option would be for the UK to replicate the EU’s GSP+ program and help LDCs transition into that as they graduate, as the EU did with Cape Verde. But if the eligibility conditions and other provisions remain the same, this will not be an option for some graduating LDCs. Most notably, Bangladesh would not meet the vulnerability criteria that exclude large exporters and other apparel exporters would struggle with the more restrictive rules of origin (Annex A). In other cases, countries may not be ready to take on the commitments involved with ratifying and effectively implementing 27 international conventions related to labor standards, the environment and good governance.

Whether or not GSP+ is an option, the UK—and other preference providers—should have a clear strategy for graduation that includes a transition period—such as the three years that the EU currently offers. During that period, full benefits continue. This gives a graduating country, which is likely to still be relatively poor, additional time to consolidate its progress. At that point, however, a sudden jump in tariffs could still have a significant negative impact on the country’s exports.

To avoid sudden trade shocks related to graduation, the UK should go beyond what the EU does and phase in the higher MFN or standard GSP tariffs slowly, adding no more than, say, two to three percentage points per year. So, for example, an apparel exporter transitioning to a MFN tariff of 12 percent would gain an additional four to six years to adjust to increased competition from other exporters.[7] The gradual phasing in of UK tariffs should be authorized in the trade preference legislation and it should apply automatically to all graduating LDCs—unless they become ineligible for another reasons. Since it would be available equally to all LDCs, it should not conflict with World Trade Organization rules governing nondiscrimination (Annex A).

In addition, just as countries have safeguards to address sudden import surges that injure domestic industries, including under the GSP regulation, the UK should adopt a reverse safeguard for preference recipients that would temporarily suspend tariff increases if a former LDC’s exports drop dramatically. These measures would keep pressure on the exporting country to improve its competitiveness while giving it space to do so. And, if it does not, tariffs could be reinstated.

Trade Preferences, Human Rights and Good Governance

Competitiveness is not the only challenge that some potential graduates face. The three largest users of the EBA program are Bangladesh, Cambodia, and Myanmar, and all three are currently involved in an “enhanced engagement” process with the EU as a result of serious concerns about human rights.[8] Cambodia’s government has become increasingly autocratic and repressive over the years and its continued eligibility for the EBA is currently under formal review. EU officials are also discussing with Myanmar the military’s actions against the Rohingya minority that sent nearly 1 million of them fleeing to Bangladesh. And with Bangladesh, the EU is pushing for further reforms to ensure the safety and freedom of association rights of garment industry workers in the wake of the Rana Plaza building collapse in which more than a thousand workers died.

In general, most preference providers seem to have taken the view that economic development can help strengthen political institutions and facilitate the development of democracy as well. Thus, LDC trade preferences have not been tightly tied to political conditions and when the programs were introduced, all LDCs were generally eligible. That creates a dilemma for countries deciding what to do in cases such as those described above. On the one hand, the EU and other preference providers do not want to be seen as rewarding serious human rights abuses. On the other hand, revoking preferential market access would potentially punish hundreds of thousands of workers, many of them female, who could lose jobs as a result.

The EU’s GSP+ program offers a carrot to persuade countries to improve protections for workers and the environment in return for additional trade access.[9] In the case of a graduating LDC, however, the GSP+ carrot can look more like a stick because they face the loss of significant market access if they do not meet the extensive eligibility conditions. Recognizing the potential costs, the UK will have to decide what degree of conditionality is useful, reasonable, and necessary for political support.

Summary and Recommendations

When LDCs are deemed to no longer need that designation, they are often just a little bit richer and a little less vulnerable to shocks than they were the day before. For that reason, the UN process for graduation is relatively long and the relevant UN bodies emphasize the need for development partners to take steps to ensure the transition is as smooth as possible. The transition risks being highly disruptive because MFN, and even standard GSP, tariffs on key products are in double digits.

Measures to mitigate the trade shock include extended periods in which former LDCs can continue to receive special treatment, including duty-free, quota-free market access for their exports. But only the EU systematically provides such a transition period, and at the end of the period, graduates still face a potentially significant jump in the tariffs their exports face.

British policymakers can create a model for doing this better by going beyond the EU’s EBA program, the current gold standard for LDC trade preferences. In addition to providing a post-graduation transition period of at least three years, the UK should also provide a period beyond that during which tariffs will be phased in gradually and in which the increases can be suspended if the former LDC suffers a sudden drop in exports. Policymakers should avoid introducing new political conditions during this period, though preferences may still be suspended or withdrawn in the face of violence or other serious human rights abuses.

This enhanced transition would help recently graduated LDCs consolidate their progress in raising incomes and reducing poverty. And it would cost the UK government nothing. Indeed, British firms and consumers would benefit by avoiding the potential for sudden price increases and disruptions to supply chains. It simply makes no sense to provide preferences for years and then yank them away just as the country is emerging from the depths of poverty.

To read the accompanying annexes, please refer to the PDF version of this Note.

[1] Maximiliano Mendez-Parra provides a summary of these programs in Designing a New UK Preferences Regime Post-Brexit, ODI Working Paper 521, London: Overseas Development Institute.

[2] This commitment is contained in the Taxation (Cross-Border Trade) Act, 2018, c.22(10), which bars the government from introducing a trade preference scheme that applies tariffs on LDC imports, see http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2018/22/section/10/enacted.

[3] Alassane Drabo and Patrick Guillaumont, Graduation from the category of least developed countries: Rationale, achievement and prospects, Development Policies Working Paper 208, Fondation pour les Etudes et Recherches sur le Developpement Inernational (FERDI), December 2017, p. 1.

[4] The UK government released a temporary tariff schedule in case of a no-deal Brexit that eliminates tariffs on bicycles, carpets, footwear, and other products, meaning exporters could face a near-term preference erosion problem rather than a longer-term graduation problem. See below and the March 2019 posts on this Overseas Development Institute blog, https://www.odi.org/blogs/10741-brexit-and-global-development.

[5] Carpets and footwear are the second most important exports, after clothing, for Nepal and Laos, respectively. Since a gradual phase-out of tariffs as proposed below would be difficult in the case of a no-deal Brexit situation, the UK government should consider targeted aid for trade to help those countries improve competitiveness and to cushion the impact. See also the ODI blog posts, op cit.

[6] The announcement of the initial schedule is here, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/temporary-tariff-regime-for-no-deal-brexit-published and that announcing the revisions here, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/temporary-tariff-regime-updated.

[7] Special provisions might be necessary for agricultural products such as sugar and meat that are subject to quantitative restrictions and face MFN tariff equivalents of 50-80 percent; see Mendez-Parra op cit., p. 12.

[8] See here https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/development/generalised-scheme-of-preferences/ and here https://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-19-882_en.htm.

[9] The EU can suspend GSP+ benefits if it concludes that a country is no longer in compliance, and it has done so in the case of Sri Lanka. But that is a different situation than an LDC being faced with the sudden loss of EBA preferences that it has enjoyed for many years.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.