Recommended

CGD’s COVID-19 Gender and Development Initiative

As donor institutions and governments seek to provide relief and support recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and global recession, CGD’s COVID-19 Gender and Development Initiative aims to ensure that their policy and investment decisions equitably benefit women and girls. We seek to support decision-makers in understanding the gendered impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic; assess health, economic, and social policy response measures with a gender lens; and propose evidence-based solutions for an inclusive recovery. Recognizing that the dialogue to date has largely emphasized challenges facing women and girls in high-income settings, our analysis centers on women and girls in low- and middle-income countries.

In this policy brief, we summarize the findings of a CGD working paper, The Gendered Dimensions of Social Protection in the COVID-19 Context. We explore the role of social protection, with an emphasis on social assistance policies and programs, in addressing increasing poverty, food insecurity, unpaid care work, and gender-based violence—all exacerbated by the onset of the crisis and associated containment measures. We document these trends and how they disproportionately impact women and girls, as well as the extent to which governments and donors are integrating a gender lens into their social protection efforts and make recommendations to ensure that future efforts effectively reach and benefit women and girls.

What is the problem?

The COVID-19 crisis has caused widespread losses in employment and income, leading to increases in household poverty and food insecurity that risk disproportionately impacting women and girls. In January 2021, the World Bank’s Global Economic Prospects report estimated that between 119 and 124 million people fell into extreme poverty (living on less than $1.90/day) in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 crisis. Before the pandemic, for every 100 men between the ages of 25 and 34, there were 122 women in the same age group living in poor households globally; even in non-poor households, women and girls may receive smaller shares of household resources. With the onset of the crisis, early analyses predict that women and girls will be especially vulnerable to impacts on poverty. Notably, these analyses do not consider recent evidence on the crisis’s disproportionate negative impacts on women’s employment, business operations, and unpaid care work (unpacked in detail in an accompanying working paper and policy brief on women’s economic empowerment in the COVID-19 context).

Around the globe, food production and distribution systems have also been impacted by the pandemic. The World Food Programme estimates that in low- and middle-income countries, the number of acutely food insecure people will nearly double, increasing 96 percent from 135 million people to 265 million. In the face of crisis-induced shocks, women and girls are more likely than men and boys to adopt negative coping behaviors around food consumption such as eating less preferred foods, eating smaller and fewer meals, decreasing food variety, and substituting more filling food for more nutritious food. Across 40 countries, 41 percent of women report a lack of food as a main impact of the pandemic, compared to 30 percent of men.

Unpaid care work has increased since the onset of the pandemic, though too little is known about the implications of COVID-19 for unpaid care work done by women and girls in lower-income countries. Increases in overall time burdens (paid and unpaid work) may be concentrated at the ends of the spectrum; these ends of the spectrum include women with higher incomes and levels of education who were previously able to rely on schools, childcare centers, and domestic workers to manage paid work and caregiving responsibilities, and, on the other end, more vulnerable women heads of households. A nationally representative study in Colombia found that the probability of women citing domestic work as their primary activity grew 5.7 percentage points since the pandemic, and 13.5 percentage points for women heads of household.

Prior to the pandemic, one in three women globally had experienced physical or sexual violence, and the crisis has exacerbated the risk of violence. As of December 2020, Peterman and O’Donnell (2020) reviewed 74 papers documenting violence against women and children in the COVID context. Among the 44 studies that examine trends or impacts, nearly half of the studies reviewed (45 percent) found an increase in violence during COVID-19, and another 25 percent reported mixed results with an increase in at least one measure of violence. Where studies observe mixed findings or decreases, underreporting may account for results, which is a cause for concern as victims are less able to report violence and seek help under lockdown conditions.

Preliminary findings are based on limited data, especially for low-income countries. Data collection efforts in the context of COVID-19 are likely to replicate long-standing measurement challenges, including a lack of individual-level poverty and food insecurity data, and the undercounting and underreporting of women’s paid and unpaid work. Sampling biases linked to the use of phone surveys as the primary collection method during the pandemic also add to these challenges, suggesting that the emerging evidence is not capturing adequately the impact of COVID-19 on the poorest and therefore most vulnerable women and girls.

What are donors and policymakers doing in response?

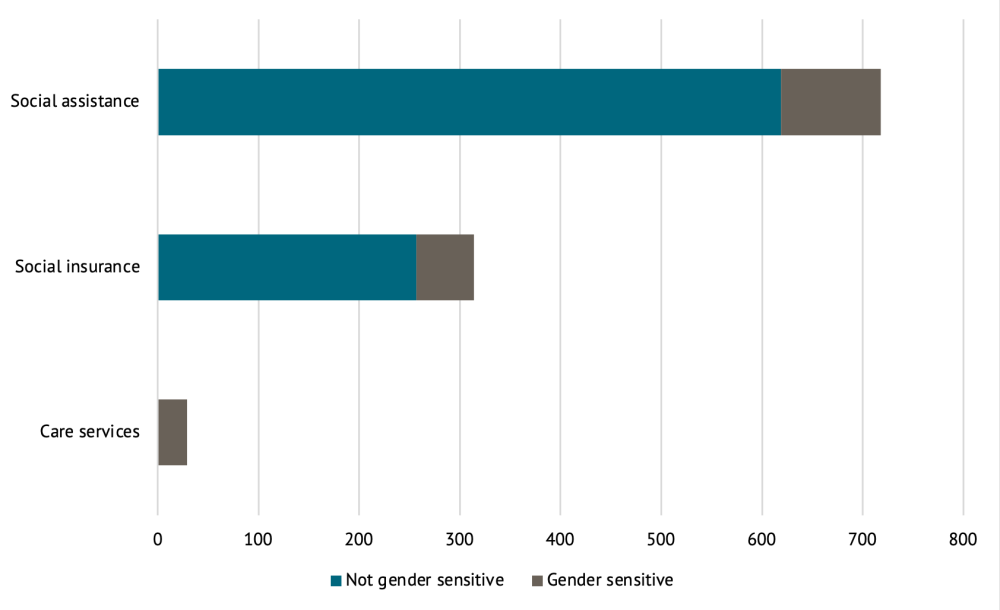

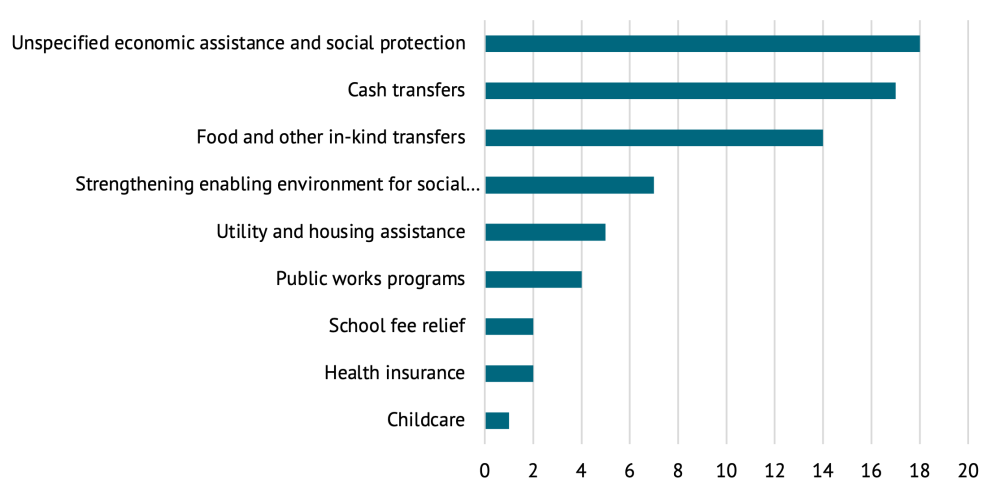

Just 17 percent of social protection policy measures announced in response to COVID-19 are gender-sensitive. According to the COVID-19 Global Gender Response Tracker, 68 percent of gender-sensitive measures fall within the bucket of social assistance, with social insurance comprising 30 percent of measures, and just 2 percent focused on unpaid care. Of 81 social assistance measures targeting women’s economic security, 63 percent are either new or adapted/expanded cash transfer programs, 26 percent are in-kind support, 5 percent are public works programs, 3.7 percent are social pensions, and 2.5 percent are utility and housing assistance.

Notably, the tracker neither provides data on policy implementation, nor evaluates the sufficiency of assistance in terms of duration or size of benefits, so more research is needed to interrogate whether these measures are meeting populations’ needs, including the extent to which they are reaching and benefiting women and girls. We find that at least 37 measures are designed to be temporary—often covering a 2–4-month window—suggesting the need for longer-term forms of support for vulnerable populations.

Figure 1. Governments’ social protection measures by category and gender sensitivity

Source: UNDP COVID-19 Global Gender Response Tracker

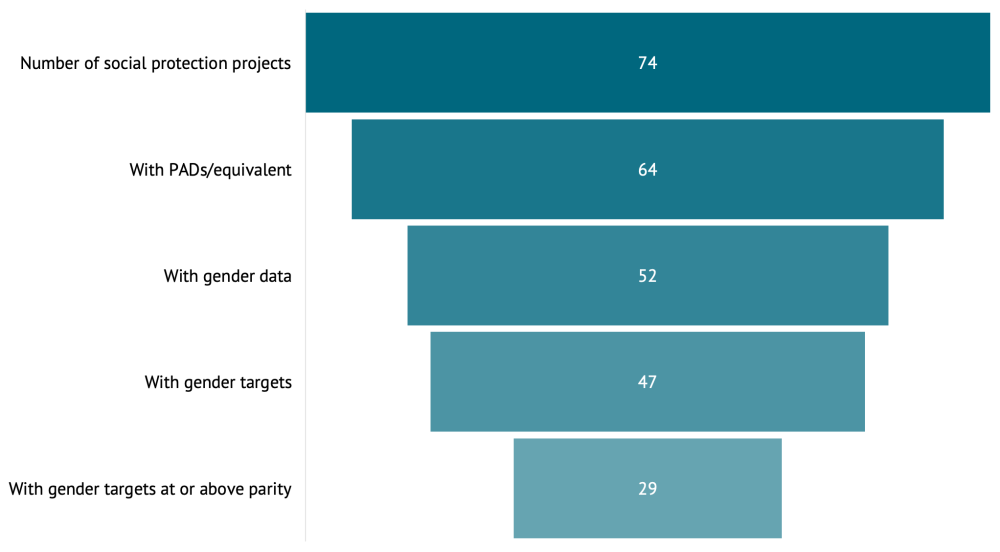

To complement national data, we review project documents from multilateral development banks to gauge the extent to which MDBs are integrating gender into their COVID-19 social protection efforts. Of 195 projects identified (approved between March and December 2020 by the World Bank, African Development Bank, and Asian Development Bank), 74 projects contain social protection components (most are focused on addressing the pandemic’s direct health effects). Of those 64 projects with publicly available documents, 81 percent include gender-focused indicators and/or targets (though just 27 percent call for intersectional data). The most commonly deployed measures are cash transfers, with only one project including an indicator focused on childcare.

Figure 2. MDB projects with social protection components, Mar. 1 – Dec. 31, 2020

Figure 3. MDB social protection projects with gender-focused indicators

What else is needed?

Generate more data and evidence

- Fill data gaps on the gendered impacts of the COVID crisis in low- and middle-income countries, especially for those who cannot be reached by the mobile phone surveys deployed to track the crisis’s effects.

- Increase collection of sex-disaggregated data on beneficiaries of social protection programs. Because the household has traditionally been the smallest unit of analysis for most data collection concerning social protection systems, too little is known about how cash transfers and other programs reach and benefit people of different genders and age groups within the household.

- Monitor and evaluate the benefits of COVID-19 related social protection measures on women and girls. Rigorous M&E and impact evaluation should follow and build on the strong evaluation record of past well-known social protection programs (i.e., Progresa in Mexico, Bolsa Familia in Brazil) and add measures on impacts focused on the well-being and empowerment of women and girls.

- Identify a harmonized set of core indicators to track the impact of social protection by gender. MDB social protection teams should consider instituting a core (concise) set of indicators that allow for standardized data collection and use across projects and contexts. This set ideally should include a simplified measure (or measures) of women’s economic empowerment that can be used cross-culturally.

- Improve single and social registries to be inclusive and cover the most vulnerable women and girls. Governments are relying on existing registry systems, as well as seeking to strengthen them, to ensure social protection programs are mobilized quickly and are inclusive in their reach. Methods to identify new recipients need to ensure that social registries have universal coverage and that socially excluded groups (including non-traditional families and gender minorities) are not left out.

Act using existing data and evidence

- Target cash benefits to women and girls. Cash transfers are a tool to protect income and empowerment gains that the pandemic threatens—though only if designed and implemented in a way that considers pre-existing gender gaps (e.g., in access to ID, mobile phones, and bank accounts, as well as time and mobility constraints that women disproportionately face) and aimed at reinforcing women’s financial independence (for instance, by opening mobile savings accounts in their names).

- Harness digital platforms, including mobile phones, to deliver benefits to women and girls—but only if information and communications technology access and knowledge are gender-equal. Individual mobile bank accounts and mobile savings accounts provide privacy and foster empowerment. They can be used to deliver cash assistance to women and girls, but need to ensure privacy and coverage, and may need to be combined with financial literacy to ensure usage of mobile accounts.

- Bundle social assistance with other interventions to address gender-specific constraints, including interventions that aim to address gender-based violence or unpaid care work. Grievance redress mechanisms should be in place in social protection programs and equipped to make referrals to support services for violence survivors.

- Use cash assistance as a medium-term strategy to promote women’s economic autonomy. Instead of halting or scaling down emergency social assistance programs, governments should consider harnessing the opportunity created through the incorporation of vulnerable households into new and expanded social assistance. Cash transfers represent an important medium-term strategy helping to alleviate the disproportionate hit to women’s employment, and consequently economic autonomy, during the pandemic. The benefits of cash transfers can be reinforced with the implementation of affordable care services, among other interventions, in order to promote women’s economic autonomy through paid employment over the long-term.

This brief is based on the CGD working paper The Gendered Dimensions of Social Protection in the COVID-19 Context. To read the full paper, including citations, please visit cgdev.org/covidandgender

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.