The US Agency for International Development (USAID) is the lead US development agency, managing roughly $20 billion in annual appropriations. The agency operates in over 120 countries, including the world’s poorest and most fragile. Its work spans a wide range of sectors, supporting humanitarian relief, economic growth, health, education, and more. USAID’s broad remit reflects the agency’s mission: “We partner to end extreme poverty and promote resilient, democratic societies while advancing our security and prosperity.”[1]

Structure and Organization

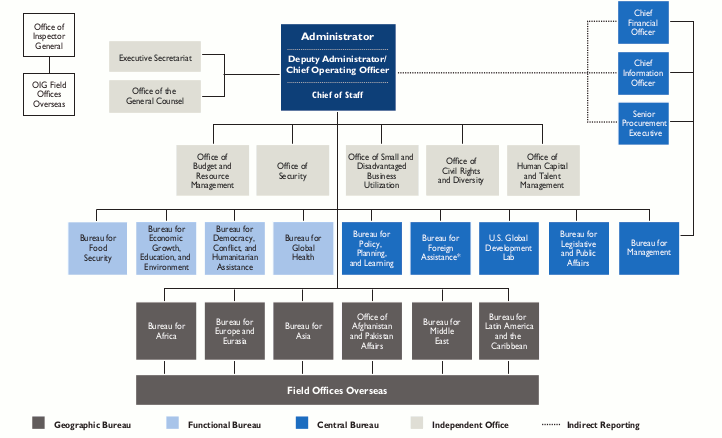

USAID’s 12 central bureaus and independent offices—located in the agency’s Washington, DC headquarters—provide policy guidance along with administrative, research, and technical support to more than 60 field missions. USAID missions are tasked with country-level agenda setting as well as project design, implementation, and evaluation. [2] The President typically nominates 13 positions at USAID, 12 of which require Senate confirmation, including the agency’s inspector general.[3]

While USAID is an independent agency, it lacks full independent authority over its budget and receives policy guidance from the Department of State. The dynamics of USAID’s relationship to the Department of State are complex and have evolved over time.

In 1998, Congress passed legislation requiring USAID’s administrator to “report to and be under the direct authority and foreign policy guidance of the Secretary of State.” The same bill mandated a reorganization plan from the president addressing the “consolidation and streamlining of the Agency and the transfer of certain functions” to the Department of State.[5] President Bill Clinton issued Executive Order 13118 to guide implementation of the legislated changes. But even in light of new reporting requirements, the order maintained “The United States Agency for International Development is an independent establishment within the Executive branch.”[6]

Another significant change occurred in 2006, when the George W. Bush administration created the State Department role of director of foreign assistance, which was held concurrently by the administrator of USAID. This dual-hatted arrangement gave the USAID administrator greater influence and authority over budget and planning processes, but some observers warned it was a “de facto merger” that could cloud US foreign aid objectives and effectively weaken the agency’s own management capacity.[7] Ultimately the change was short-lived. The Barack Obama administration maintained the Office of US Foreign Assistance (F Bureau) at the State Department, but determined that USAID’s administrator would no longer serve as its director. Under the banner of elevating development policy, the Obama administration also reestablished a policy office within USAID. Today, State retains significant budgetary authority over USAID. USAID and State submit a joint congressional budget justification to accompany the president’s annual budget request, and periodically detail future direction and priorities in a joint strategic plan.[8] But USAID’s Bureau for Policy, Planning and Learning (PPL) ensures the agency has an independent voice in interagency policy discussions and plays a critical role in overseeing its strategic direction. PPL is also uniquely positioned to look across the agency’s range of programs to understand what works and what does not—and to use evidence to drive policy decisions.

Budget

Most funding for USAID is appropriated through the Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations bill. The notable exception is funding for international food aid under the Food for Peace program, also known as P.L. 480, which is funded through Agriculture appropriations legislation. USAID manages over one-third of the International Affairs budget (“150” account).[9]

Because USAID jointly manages a number of funds with the State Department, budget figures for the agency alone are estimates. In some cases, USAID receives additional funding through transfers from the other agencies. The following accounts are “core” accounts that typically have fallen under the jurisdiction of USAID.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Global Health - USAID | 2,519 | 2,498 | 2,625 | 2,626 | 2,770 | 3,096 | 2,755 | 2,834 |

| Development Assistance | 2,520 | 2,520 | 2,520 | 2,718 | 2,507 | 2,507 | 2,781 | 2,960 |

| International Disaster Assistance | 845 | 863 | 1,095 | 1,550 | 1,801 | 3,331 | 2,794 | 1,957 |

| Transition Initiatives | 55 | 55 | 94 | 69 | 58 | 67 | 67 | 78 |

| Complex Crises Fund | 50 | 40 | 50 | 53 | 40 | 50 | 30 | 30 |

| Development Credit Authority - Subsidy | -25 | -30 | -40 | -40 | -40 | -40 | -40 | -60 |

| Development Credit Authority - Administrative Expenses | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 10 |

| Food for Peace Act Title II | 1,690 | 1,497 | 1,466 | 1,359 | 1,466 | 1,466 | 1,716 | 1,350 |

| USAID Operating Expenses | 1,389 | 1,347 | 1,347 | 1,279 | 1,140 | 1,235 | 1,283 | 1,405 |

| USAID Capital Investment Fund | 185 | 130 | 130 | 123 | 118 | 131 | 168 | 200 |

| USAID Inspector General Operating Expenses | 50 | 46 | 51 | 48 | 55 | 60 | 66 | 68 |

USAID’s administrative costs are funded through the Operating Expenses and the Capital Investment Fund accounts. Operating Expenses supports the salary, benefits, security, and other human capital needs of the agency, while the Capital Investment Fund supports facility construction, information technology, and property maintenance.[11]

USAID also implements a sizable portion of funding from the State Department’s Global Health account and co-manages with State the Economic Support Fund (ESF), Assistance for Europe, Eurasia, & Central Asia (AEECA), and the Democracy Fund. USAID is a major implementing partner of global health programs under the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), which is overseen by State’s Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator. USAID implements ESF programming in democracy, human rights, governance, economic growth, and agriculture. Other agencies, also implement programs funded by ESF and State-administered global health account.

USAID’s Approach

USAID relies primarily on grant-based financing, employing a range of project designs and mechanisms, including competitive grants, contracts, cooperative agreements, public-private partnerships, government-to-government assistance, and host country contracts.[12] Projects are carried out by a wide variety of development partners, though American organizations remain the largest implementers of USAID programs. Nearly half of USAID’s procurements went to US-based for-profit and nonprofit organizations in FY2014.[13] All large and innovative projects must undergo evaluation, according to agency policy.[14] USAID has dramatically increased the number of evaluations it conducts each year, from 82 in FY2006 to 246 in FY2015.[15]

In 2010, the agency launched a reform agenda dubbed USAID Forward, which set out to increase the agency’s capacity to deliver results, promote partnerships to ensure development gains are sustained, and encourage innovation to tackle development challenges.[16] The agency outlined a range of targets designed to measure progress toward its greater objectives. USAID has issued regular data and reports detailing its achievements under the Forward agenda.[17]

To help ensure the agency’s activities are appropriately tailored to a particular context and align with both US and recipient country objectives, each mission is required to develop a five-year planning document known as a Country Development Cooperation Strategy (CDCS). The CDCSs are meant to reflect local priorities and circumstances, while taking into account policy priorities and spending directives from Washington. But according to a 2015 report from USAID’s Office of the Inspector General, presidential initiatives and congressional directives often constrained mission decisions.[18]

Activities

Of the US agencies working to advance development, USAID has the widest remit in geographic range and sector. USAID operates in over 120 countries, including fragile and conflict-affected states.[19] USAID’s activities seek to address a vast range of development challenges, from health and food security to economic growth and democracy. USAID also serves as the lead US agency providing humanitarian assistance. In addition to the five areas of work profiled below, USAID is active in other sectors, including education, water, and sanitation. Several cross-cutting issues, such as ending extreme poverty, promoting gender equality and women’s empowerment, and combating global climate change, are integrated into USAID’s programming across sectors. Recently, USAID has increased investment in innovation, creating the US Global Development Lab and initiatives like Development Innovations Ventures, which seek to inspire and test new solutions to development challenges.[20]

Responding to and Averting Crisis: USAID is a leader in delivering humanitarian aid. The agency delivers this assistance through its Office of US Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) under the Bureau for Democracy, Conflict, and Humanitarian Assistance (DCHA). Through OFDA, USAID helps countries prepare for, respond to, and recover from humanitarian crises, including both man-made and natural disasters. OFDA was founded in 1964 with a mandate to save lives, alleviate human suffering, and reduce the social and economic impact of disasters. In the event of a crisis or disaster, OFDA deploys a Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART) to coordinate the US government response on the ground. The DART-organized response may include supporting health service delivery, building latrines, and facilitating the distribution of emergency relief supplies—such as blankets, emergency shelters, and hygiene kits.[21] OFDA also activates a Response Management Team at USAID’s headquarters to engage in response planning and liaise with other US government agencies. In FY2016, OFDA had six DARTs in the field, responding to crises in Syria, South Sudan, Iraq, West Africa, and Ethiopia.[22] In addition to disaster response, USAID works in countries to prevent conflict and prepare for future natural disasters. By statute, USAID’s Office of Food for Peace manages emergency food assistance to address the immediate food and nutrition needs of vulnerable populations.[23]

The budget for humanitarian assistance is primarily drawn from the International Disaster Assistance account. The Transition Initiatives account funds projects in countries transitioning out of conflict, and the Complex Crises Fund supports projects that address the root causes of conflict in emerging crises.[24] The Office of Food and Peace, a separate office under DCHA, manages most international food assistance. While considered part of the foreign affairs budget, funding for the Food for Peace program—which relies heavily on in-kind food aid—is appropriated through the Agriculture appropriations bill, and the program’s authorization is regularly renewed through the Farm bill. Some of this food assistance is delivered in response to emergencies, but the program also supports efforts to address the more chronic challenges of hunger and malnutrition.[25]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| International Disaster Assistance | 845 | 863 | 1,095 | 1,550 | 1,801 | 3,331 | 2,794 | 1,957 |

| Transition Initiatives | 55 | 55 | 94 | 69 | 58 | 67 | 67 | 78 |

| Complex Crises Fund | 50 | 40 | 50 | 53 | 40 | 50 | 30 | 30 |

| P.L. 480, Title II | 1,690 | 1,497 | 1,466 | 1,359 | 1,466 | 1,466 | 1,716 | 1,350 |

Advancing Global Health: Several US agencies are engaged in efforts to promote global health, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and the Department of State.[27] USAID funds health service provision and supports health care systems in low- and middle-income countries. The agency’s global health activities, coordinated by the Bureau of Global Health, cover a wide range of health needs, addressing HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, maternal and child health, family planning, and nutrition. USAID’s maternal and child health programs are currently active in 25 countries that together account for two-thirds of the world’s maternal and child deaths. USAID is also the world’s largest bilateral funder of family planning programs around the world; these focus on improving access to modern contraceptive methods and ensuring women’s reproductive health.[28] As an implementing agency under PEPFAR, USAID provides training and technical assistance to prevent the transmission of HIV/AIDS, treatment for people living with HIV/AIDS, and support for programs in other sectors linked to HIV/AIDS.[29] The agency also supports efforts to improve the screening, diagnostics, and treatment services for infectious diseases like tuberculosis and malaria. Specifically, USAID works with CDC/HHS to implement the President’s Malaria Initiative, which President George W. Bush launched to reduce malaria mortality by 50 percent in 19 African focus countries plus a region of southeast Asia.[30] As the US representative on the GAVI Alliance, the agency advocates increased access to vaccines for children in the world’s poorest countries.[31]

USAID receives direct appropriations for global health programs, and as a key implementing partner under PEPFAR is responsible for implementing programs funded through the State Department as well.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Global Health - USAID | 2,519 | 2,498 | 2,625 | 2,626 | 2,770 | 2,784 | 2,755 | 2,834 |

| …of which HIV/AIDS | 350 | 349 | 350 | 333 | 330 | 330 | 330 | 330 |

| …of which Tuberculosis | 225 | 225 | 236 | 225 | 236 | 236 | 191 | 236 |

| …of which Malaria | 585 | 619 | 650 | 656 | 665 | 670 | 674 | 674 |

| …of which Maternal and Child Health | 474 | 549 | 606 | 627 | 705 | 715 | 770 | 750 |

| …of which Nutrition | 75 | 89 | 95 | 95 | 115 | 115 | 101 | 125 |

| …of which Vulnerable Children | 15 | 15 | 18 | 17 | 22 | 22 | 15 | 22 |

| …of which Family Planning/Reproductive Health | 529 | 527 | 524 | 532 | 524 | 524 | 538 | 524 |

| ...of which Neglected Tropical Diseases | 65 | 77 | 89 | 86 | 100 | 100 | 87 | 100 |

| …of which Global Health Security/Pandemic Influenza and Other Emerging Threats | 201 | 48 | 58 | 55 | 73 | 73 | 50 | 73 |

Promoting Democracy, Human Rights, and Governance (DRG): USAID’s support for democracy, human rights, and governance fits squarely within the agency’s mission to promote democratic societies. Assistance in this area aims to serve US national interests by promoting security and stability in countries around the world. USAID’s DRG activities are largely coordinated by the Bureau for Democracy, Conflict, and Humanitarian Assistance (DCHA). The agency’s activities in this area have included strengthening civil society and electoral management bodies, expanding voter education, and monitoring electoral processes.[33] Along with State, USAID also works closely with governments and civil society to counter human trafficking.[34]

USAID’s budget for DRG is largely funded by the USAID-managed Development Assistance (DA) and the State-USAID jointly managed Economic Support Fund (ESF) accounts. In FY2015, USAID allocated $152 million from DA, $1,223 million from ESF, and $131 million from the Democracy Fund to DRG programs.[35]

Promoting Economic Growth to End Extreme Poverty: Broad-based economic growth is central to USAID’s mission to end extreme poverty. Economic growth is also key to countries achieving greater self-reliance through the mobilization of domestic resources to finance development. And USAID’s economic growth programs promote US interests by helping to build new markets for American companies and encourage political stability.[36] USAID’s Bureau for Economic Growth, Education, and the Environment (E3) provides leadership in this area.

USAID’s work to further economic growth encompasses projects focused on infrastructure, trade, financial inclusion, and private investment. For instance, USAID has facilitated electric power, transportation, communications, and water infrastructure through direct support for design, construction, and rehabilitation, as well as efforts to improve countries’ policy and regulatory environments. USAID is the lead agency tasked with coordinating Power Africa, an initiative launched by President Barack Obama that aims to add 30,000 megawatts of cleaner electricity generation capacity and make at least 60 million new electricity connections—residential and commercial—in sub-Saharan Africa.[37] Meanwhile, USAID’s Office of Trade and Regulatory Reform works with government officials to implement trade agreements and improve trade facilitation. USAID’s Development Credit Authority offers partial credit guarantees backed by the US Treasury, which facilitate access to financing for small businesses in emerging markets.[38] The agency also implements projects to train entrepreneurs in developing countries and connect them with markets.

USAID’s budget for economic growth is largely funded by the DA and the ESF accounts. In FY2015, USAID allocated $771 million from DA and $1,868 million from ESF to a range of programs focused on economic growth.[39]

Investing in Agriculture and Food Security: Improving food security and nutrition have been important areas of focus for USAID in recent years under the Feed the Future Initiative. Launched in 2010, and authorized by Congress in 2016, Feed the Future is an interagency food security initiative led by USAID through the Bureau of Food Security. Many of the world’s poor live in rural areas, where a strong agricultural sector can be critical to reducing poverty. Poverty, in turn, is tightly linked to food insecurity and malnutrition. Investing in countries’ agricultural sectors can boost productivity and increase the availability and accessibility of food.[40] Feed the Future has focused its support in 19 countries, where it works to improve agricultural markets, help producers access capital, and provide farmers with tools and technical assistance to increase yields of target crops. In Ethiopia, Feed the Future has helped 200,000 people increase their annual income by an average of $330 through support for the Ethiopian Government’s Productive Safety Net Program.[41] Under Feed the Future, USAID places special emphasis on engaging women, the extreme poor, small-scale producers, and youth.[42] USAID also works to encourage policy reforms that would drive investment into countries’ agriculture sectors and reduce hunger and malnutrition.

USAID’s agriculture programs are mostly funded through the DA account, which allocated $900 million to promoting food security in FY2015.[43]

Endnotes

[1] USAID, “Mission, Vision and Values,” USAID, 2017, https://www.usaid.gov/who-we-are/mission-vision-values.

[2] Curt Tarnoff, “U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID): Background, Operations, and Issues,” CRS Report (Congressional Research Service, July 21, 2015), https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R44117.pdf.

[3] Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, “United States Government Policy and Support Positions” (US Government Publishing Office, December 1, 2016), https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/GPO-PLUMBOOK-2016/pdf/GPO-PLUMBOOK-2016.pdf. Positions subject to Presidential appointment with Senate confirmation include the administrator, deputy administrator, inspector general, and assistant administrators.

[4] USAID, “Organization,” USAID, February 13, 2017, https://www.usaid.gov/who-we-are/organization.

[5] U.S. Congress, “Omnibus Consolidated Appropriations,” Pub. L. No. 105–277 (1998), https://www.congress.gov/105/plaws/publ277/PLAW-105publ277.pdf.

[6] William J. Clinton, “Executive Order 13118 - Implementation of the Foreign Affairs Reform and Restructuring Act of 1998.” (The White House, March 31, 1999), https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2000-title3-vol1/pdf/CFR-2000-title3-vol1-eo13118.pdf.

[7] Kate Almquist Knopf, “USAID: Destined to Disappoint,” Center For Global Development, US Development Policy, (August 2, 2013), /blog/usaid-destined-disappoint; Steve Radelet, “Sec. Rice’s Aid Reform Plan Falls Short,” Center For Global Development, Views from the Center, (January 19, 2006), /blog/sec-rices-aid-reform-plan-falls-short; Center for Global Development, “Better Late than Never: Bush Administration Includes Poverty Reduction as Goal of Foreign Aid,” Center For Global Development, Views from the Center, (February 2, 2007), /blog/better-late-never-bush-administration-includes-poverty-reduction-goal-foreign-aid.

[8] Tarnoff, “U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID): Background, Operations, and Issues.”

[9] The International Affairs budget mostly overlaps with the State and Foreign Operations bill, with some exceptions like Food for Peace (included in the International Affairs budget but not in the State and Foreign Operations bill). Susan B. Epstein, Marian L. Lawson, and Alex Tiersky, “State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs: FY2016 Budget and Appropriations,” CRS Report (Congressional Research Service, November 5, 2015), https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R43901.pdf; Tarnoff, “U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID): Background, Operations, and Issues.”

[10] U.S. Department of State, “Congressional Budget Justification - Foreign Assistance Summary Tables (FY2012-FY2017).” (U.S. Department of State, 2016), https://www.usaid.gov/results-and-data/budget-spending/congressional-budget-justification; Tiaji Salaam-Blyther, “U.S. Global Health Assistance: FY2001-FY2016,” CRS Report (Congressional Research Service, May 11, 2015), https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20150511_R43115_ba0326d0d7a8165a23e28340e40389fc536c1ed2.pdf. The FY15 column includes Ebola-related appropriations. The Global Health-USAID budget summary is sourced from Salaam-Blyther. It should be noted that there are some inconsistencies between the budget summary for Global Health-USAID between the Congressional Budget Justifications and Salaam-Blyther.

[11] U.S. Department of State, “Congressional Budget Justification: Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs - Fiscal Year 2017” (U.S. Department of State, 2016), https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/9276/252179.pdf.

[12] Tarnoff, “U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID): Background, Operations, and Issues”; USAID, “Program Cycle Overview.” (USAID, December 9, 2011), http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pdacs774.pdf.

[13] Tarnoff, “U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID): Background, Operations, and Issues,” 47.

[14] USAID, “USAID Evaluation Policy.” (USAID, October 2011), https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1870/USAIDEvaluationPolicy.pdf.

[15] USAID, “Strengthening Evidence-Based Development - Five Years of Better Evaluation Practice at USAID” (USAID, 2016), 14, https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1870/Strengthening%20Evidence-Based%20Development%20-%20Five%20Years%20of%20Better%20Evaluation%20Practice%20at%20USAID.pdf.

[16] USAID, “USAID Forward,” USAID, January 19, 2017, https://www.usaid.gov/usaidforward.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Office of Inspector General, USAID, “Audit of USAID Country and Regional Development Cooperation Strategies” (Office of Inspector, USAID, February 20, 2015), http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00KB67.pdf. According to anecdotal evidence, directives account for 90 percent of available program funds in some USAID missions, including Indonesia and Mozambique.

[19] USAID, “Foreign Aid Explorer: The Official Record of U.S. Foreign Aid,” 2017, https://explorer.usaid.gov/data.html.

[20] Charles Kenny, “Next USAID Innovation: Learning from Failure,” Center For Global Development, US Development Policy, (June 22, 2011), /blog/next-usaid-innovation-learning-failure.

[21] USAID, “USAID’s Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance: Fact Sheet.” (USAID, 2017), https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1866/ofda_fact_sheet_02-09-2017.pdf.

[22] USAID, “Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance,” November 15, 2016, https://www.usaid.gov/who-we-are/organization/bureaus/bureau-democracy-conflict-and-humanitarian-assistance/office-us.

[23] USAID, “Office of Food for Peace,” USAID, March 6, 2017, https://www.usaid.gov/who-we-are/organization/bureaus/bureau-democracy-conflict-and-humanitarian-assistance/office-food.

[24] Curt Tarnoff and Cory G. Gill, “State, Foreign Operations Appropriations: A Guide to Component Accounts,” CRS Report (Congressional Research Service, January 9, 2017), https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R40482.pdf.

[25] USAID, “Office of Food for Peace.”

[26] U.S. Department of State, “Congressional Budget Justification - Foreign Assistance Summary Tables (FY2012-FY2017).” The FY2015 column includes funding provided through an emergency supplemental appropriations bill to combat the Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

[27] Amanda Glassman and Lauren Post, “Evolving the US Model of Global Health Engagement,” Brief (Center for Global Development, August 8, 2016), /publication/evolving-us-model-global-health-engagement.

[28] USAID, “Family Planning and Reproductive Health,” USAID, March 9, 2017, https://www.usaid.gov/what-we-do/global-health/family-planning.

[29] U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Public Affairs, “U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID),” The United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, November 15, 2006, https://www.pepfar.gov/about/agencies/c19395.htm.

[30] President’s Malaria Initiative, “About,” President’s Malaria Initiative, 2017, https://www.pmi.gov/about.

[31] Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, “Board Members,” Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, 2017, http://www.gavi.org/about/governance/gavi-board/members/.

[32] Salaam-Blyther, “U.S. Global Health Assistance: FY2001-FY2016”; U.S. Congress, “Joint Explanatory Statement of the Committee of Conference on H.R. 2029 - Division K - Department of State, Foreign Appropriations Act, 2016.” (House of Representatives Committee on Rules, 2015), http://docs.house.gov/meetings/RU/RU00/20151216/104298/HMTG-114-RU00-20151216-SD012.pdf. The FY2015 budget summary does not include Ebola-related appropriations. The FY2017 column does not include supplemental appropriations under the "Zika Response and Preparedness Act," which appropriated additional funds for Global Health Programs and Operating Expenses.

[33] The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, “FACT SHEET: U.S. Support for Democratic Institutions, Good Governance, and Human Rights in Africa,” Obamawhitehouse.archives.gov, August 4, 2014, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2014/08/04/fact-sheet-us-support-democratic-institutions-good-governance-and-human-.

[34] USAID, “Countering Trafficking in Persons,” USAID, January 18, 2017, https://www.usaid.gov/trafficking.

[35] U.S. Department of State, “Congressional Budget Justification: Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs - Fiscal Year 2017.” This figure includes funds allocated for the purposes of rule of law and human rights, good governance, political competition and consensus-building, and civil society.

[36] USAID, “Securing the Future: A Strategy for Economic Growth,” USAID, April 2008, http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pdacl254.pdf.

[37] Power Africa, “Power Africa Roadmap: A Guide to Creating 30,000 Megawatts and 60 Million Connections” (USAID, 2016), https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1860/USAID_PA_Roadmap_April_2016_TAG_508opt.pdf.

[38] USAID, “Development Credit Authority: Putting Local Wealth to Work,” USAID, 2016, https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1865/DCA_One-Pager_48.pdf.

[39] U.S. Department of State, “Congressional Budget Justification: Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs - Fiscal Year 2017.” This figure includes funds allocated for the purposes of Macroeconomic Foundation for Growth, Trade and Investment, Financial Sector, Infrastructure, Private Sector Competitiveness, and Economic Opportunity.

[40] U.S. Government, “U.S. Government Global Food Security Strategy: FY 2017-2021” (USAID, September 2016), https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1867/USG-Global-Food-Security-Strategy-2016.pdf.

[41] Feed the Future, “2016 Feed the Future Progress Report,” Feed the Future, 2016, https://feedthefuture.gov/sites/default/files/resource/files/2016%20Feed%20the%20Future%20Progress%20Report_0.pdf.

[42] U.S. Government, “U.S. Government Global Food Security Strategy: FY 2017-2021.”

[43] U.S. Department of State, “Congressional Budget Justification: Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs - Fiscal Year 2017.”

[44] Percentages refer to the portion of total USAID-implemented disbursements of foreign assistance dedicated to the sector in FY2015. The “other” category includes assistance to peace and security, education, other social and economic services, environment and program support. Data comes from the Foreign Aid Explorer. USAID, “Foreign Aid Explorer: The Official Record of U.S. Foreign Aid.”

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.