Established in 2004, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) was designed with a singular mission: to reduce poverty through economic growth. The agency’s approach reflects key principles of aid effectiveness, in particular:

Country selectivity. MCC partners only with countries that demonstrate commitment to good governance and growth-friendly policies. The approach is grounded in the idea that partnering with good policy performers rewards countries taking responsibility for their own development, creates incentives for reform, and potentially increases the effectiveness of MCC investments.[1]

Focus on results. MCC’s robust framework for results ensures that the agency focuses on binding constraints to growth, identifies economically efficient projects (i.e., those with local benefits that exceed project costs), tracks projects’ progress, and measures their impact.

Emphasis on local ownership. Partner countries take a lead role in developing and implementing programs. This approach is based on the notion that US investments will be more effective and sustainable when they support local priorities and strengthen partner governments’ accountability to their citizens.[2]

Structure and Organization

MCC is a small agency with around 300 employees. The agency’s chief executive officer (CEO) is appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate.[3] MCC’s board of directors is made up of five government representatives—the secretary of state, the USAID administrator, the secretary of the Treasury, the US trade representative, and MCC’s CEO—as well as four private representatives recommended by Congress (one each from the majority and minority in both chambers) who serve in their individual capacities. The secretary of state acts as chair.

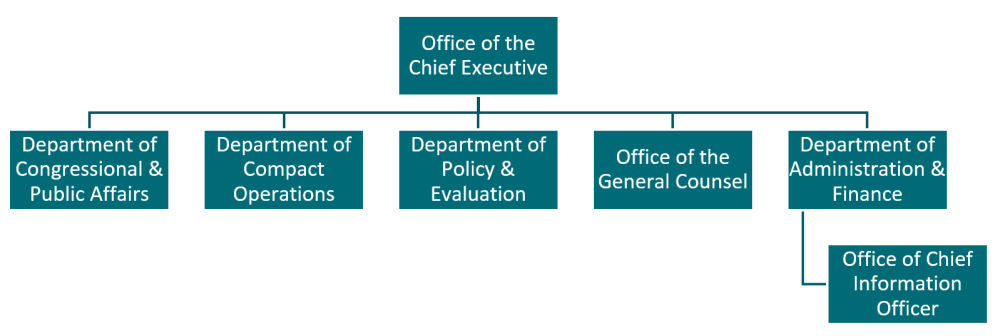

Figure 1: MCC Organizational Chart[4]

Budget

Congress authorized the MCC in the FY2004 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 108-199).[5] Funding for MCC is appropriated through annual Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations. MCC is free from the restrictions and spending directives that encumber much of US foreign assistance, allowing it the flexibility to support partner-country priorities and target results-focused investments.

|

FY10 |

FY11 |

FY12 |

FY13 |

FY14 |

FY15 |

FY16 - |

FY17 - |

|

|

Millennium Challenge Corporation |

1,105 |

900 |

898 |

898 |

898 |

899 |

901 |

1,000 |

MCC’s Approach

Country Selectivity:

MCC partners only with low- and lower-middle income countries, a categorization based on per capita income.[7] In 2017, MCC’s candidate pool included 74 countries.[8] To assess candidate countries’ relative policy performance, MCC compiles 20 quantitative, publicly available indicators from third-party sources into country “scorecards.” The indicators fall into the three broad areas: ruling justly, investing in people, and encouraging economic freedom.[9] To meet MCC’s eligibility criteria, a country must score better than a given threshold (usually the income-based peer group median) on the majority of the indicators, including the indicator that measures control of corruption and at least one of the two indicators that measure the strength of democratic rights and practices. MCC’s board of directors bases its eligibility decisions on countries’ scorecard performance, and on supplemental information that provides a more complete picture of a country’s policy performance and MCC’s opportunities to reduce poverty and promote economic growth in that country.[10] In addition to selecting countries on the basis of their governance, the agency has demonstrated an important willingness to suspend or terminate a country partnership when policy performance substantially deteriorates.[11]

Programming:

MCC’s flagship program is the country compact. A compact is a partnership agreement in which MCC provides large-scale grant financing (around $350 million, on average) over five years to a selected partner country for programs focused on poverty reduction through economic growth. To date, MCC has signed 33 compacts with 27 countries totaling approximately $11.7 billion.[12]

The agency also has a smaller threshold program that supports targeted policy reform activities in selected countries with the goal of helping the country become compact eligible. The agency has signed 26 threshold programs with 24 countries totaling approximately $584 million.[13] Initially, threshold programs primarily supported targeted policy reforms intended to help a country improve its scores on the eligibility indicators needed to pass the scorecard. In more recent years, the program has shifted to focus on gauging a country’s willingness to undertake policy reform, informed by a constraints-to-growth analysis.[14] Threshold programs have accounted for about 5 percent of MCC’s total program spending since 2004, with an average cost of around $20 million over two to three years.

Program Development:

The partner country government, in consultation with a wide range of stakeholders, takes the lead in setting priorities for MCC investments. During the initial phase of compact and threshold program development, MCC supports the partner country to undertake an integrated constraints-to-growth analysis that identifies factors limiting private investment and economic growth. The partner country proposes projects to address these constraints, and MCC, in cooperation with the country, performs a cost-benefit analysis on each proposal to ensure selected projects address constraints in a cost-efficient manner.[15]

Program Implementation:

Partner countries take a lead role in compact implementation through a dedicated accountable entity called a Millennium Challenge Account (MCA), which manages and oversees all aspects of implementation.[16] The MCA is overseen by a local board of directors that usually includes high-level government officials, as well as private sector representatives and civil society leaders.[17]

Program Evaluation:

Almost 85 percent of MCC’s portfolio by value is or will be covered by an evaluation following the program’s completion.[18] Roughly half of planned evaluations are rigorous impact evaluations, which seek to estimate the causal impact of MCC’s investments on observed outcomes.[19]

Transparency:

MCC ranks among the most transparent aid agencies worldwide.[20] The agency publishes the tools it uses to select partners (country scorecards), the analyses it uses to choose projects (constraints-to-growth analysis and cost-benefit analysis), quarterly updates on compact progress, and the results of project evaluations.

Activities

Supporting Country-identified Priorities: While MCC has funded projects in a range of sectors, infrastructure has been particularly prominent. Since the agency’s inception, more than 40 percent of its cumulative compact funding has supported investments in transportation and energy infrastructure. In countries where the economic analysis pointed to a lack of electricity as a primary growth constraint, the agency played an important role in advancing the Obama administration’s Power Africa initiative, committing more than $1.5 billion in programming to improve electricity access and renewable energy systems. MCC compacts have also invested in other sectors, including agricultural development, education, health, and property rights and land policy. MCC’s board and some members of Congress have encouraged the agency to explore the potential for compacts that promote regional integration, including through cross-border infrastructure investments, to unlock further growth potential.[21]

Encouraging Reform: MCC’s compacts include jointly developed policy conditions that the partner country government agrees to complete as part of the partnership. These often include policy, institutional, or regulatory reforms considered critical for MCC’s investments to yield sustained results.[22]

|

|

Endnotes

[1] For more on MCC and country selection, see Sarah Rose and Franck Wiebe, “Focus on Policy Performance MCC’s Model in Practice,” MCC Monitor Analysis, MCC at 10 (Center for Global Development, January 27, 2015), /publication/focus-policy-performance-mccs-model-practice.

[2] For more on MCC and country ownership, see Sarah Rose and Franck Wiebe, “Focus on Country Ownership: MCC’s Model in Practice,” MCC Monitor Analysis, MCC at 10 (Center for Global Development, January 27, 2015), /publication/focus-country-ownership-mccs-model-practice.

[3] Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, “United States Government Policy and Support Positions,” (US Government Publish Office, December 1, 2016), https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/GPO-PLUMBOOK-2016/pdf/GPO-PLUMBOOK-2016.pdf.

[4] Millennium Challenge Corporation, “Agency Financial Report Fiscal Year 2016,” (Millennium Challenge Corporation, 2016), https://assets.mcc.gov/documents/report-fy2016-afr.pdf.

[5] U.S. Congress, “Millennium Challenge Act of 2003,” Pub. L. No. 108–199, § Division D (2003), https://assets.mcc.gov/reports/mca_legislation.pdf.

[6] U.S. Department of State, “Congressional Budget Justification - Foreign Assistance Summary Tables (2012-2017),” (U.S. Department of State, 2016), https://www.usaid.gov/results-and-data/budget-spending/congressional-budget-justification.

[7] Most MCC funds support programs in low-income countries, since the agency is limited to spending 25 percent of funds in lower-middle-income countries. U.S. Congress, Millennium Challenge Act of 2003.

[8] This count excludes countries barred by law from receiving US assistance. Millennium Challenge Corporation, “Report on Countries That Are Candidates for Millennium Challenge Compact Eligibility for Fiscal Year 2017 and Countries That Would Be Candidates but for Legal Prohibitions” (Millennium Challenge Corporation, August 23, 2016), https://www.mcc.gov/resources/doc/report-candidate-country-fy-2017.

[9] Millennium Challenge Corporation, “Guide to the Indicators and the Selection Process, FY 2015,” (Millennium Challenge Corporation, October 9, 2014), https://www.mcc.gov/resources/doc/report-guide-to-the-indicators-and-the-selection-process-fy-2015.

[10] The board must also consider the amount of funds available to MCC when making eligibility determinations.

[11] Rose and Wiebe, “Focus on Country Ownership,” January 27, 2015.

[12] Curt Tarnoff, “Millennium Challenge Corporation,” CRS Report (Congressional Research Service, January 11, 2017), https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL32427.pdf; Sarah Rose and Franck Wiebe, “An Overview of the Millennium Challenge Corporation,” MCC Monitor Analysis, MCC at 10 (Center for Global Development, January 27, 2015), /publication/ft/overview-millennium-challenge-corporation.

[13] Tarnoff, “Millennium Challenge Corporation”; Rose and Wiebe, “Focus on Country Ownership,” January 27, 2015.

[14] This shift came as a result of a self-assessment that found the original objective of the threshold program was technically unrealistic. Many eligibility indicators tend to be very broad in scope (e.g., “control of corruption”) and are not appropriate for capturing the progress of more narrow programmatic interventions.

[15] Millennium Challenge Corporation, “MCC’s Use of Evidence and Evaluation,” Millennium Challenge Corporation, June 6, 2014, https://www.mcc.gov/resources/doc/factsheet-mccs-use-of-evidence-and-evaluation.

[16] Esther Pan, “FOREIGN AID: Millennium Challenge Account,” Backgrounder, (May 28, 2004), http://www.cfr.org/pakistan/foreign-aid-millennium-challenge-account/p7748.

[17] Millennium Challenge Corporation, “About MCC,” Millennium Challenge Corporation, 2017, https://www.mcc.gov/about.

[18] Rose and Wiebe, “Focus on Country Ownership,” January 27, 2015.

[19] Millennium Challenge Corporation, “MCC’s Use of Evidence and Evaluation.”

[20] Publish What You Fund, “2016 U.S. Brief,” Aid Transparency Index (Publish What You Fund, 2016).

[21] Sarah Rose, “Regional and Sub-National Compact Considerations for the Millennium Challenge Corporation,” MCC Monitor (Center for Global Development, September 4, 2014), /publication/regional-and-sub-national-compact-considerations-millennium-challenge-corporation.

[22] Rose and Wiebe, “Focus on Country Ownership,” January 27, 2015.

[23] Tarnoff, “Millennium Challenge Corporation.”

[24] Tarnoff, “Millennium Challenge Corporation.”

[25] Countries in italics denote active threshold programs

[26] Ibid.

[27] Countries in italics denote active compacts

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.