Recommended

Abstract

The World Bank today faces parallel challenges to its operations and governance. The institution has since its founding provided financing on favourable terms to developing country governments to support national development efforts. Alongside these country demands, there are now calls for a new set of mandates and activities associated with global public goods. Advocates would have the Bank allocate large sums toward climate mitigation, pandemic response and preparedness, and other activities that may or may not align with national priorities in developing countries. The ability of the World Bank to strike an appropriate balance between country demands and global goods depends on the institution’s shareholders. Yet, the deterioration in the bilateral relationship between the United States and China now threatens to undermine effective governance at the institution. This paper considers the challenge of competing demands on World Bank resources and the degree to which a resolution could depend on an agreement between the United States and China, one that sets the strategic direction of the institution and addresses the growing impasse on the question of China’s shareholding in the Bank.

Read the full article here or below.

This article was originally published in the Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Volume 39, Issue 2, Summer 2023, pp 379–88.

I. Introduction

The World Bank was created in 1944 to alleviate external financing constraints for the world’s capital-poor governments, providing US dollar loans where access to commercial lenders was limited or non-existent. As a multilateral institution, the bank benefitted from capital contributions by its member governments, a defining feature that reflected a decision by these governments to favour this pooling mechanism for at least some of their foreign aid activities.

Soon, other multilateral development banks (MDBs) were established in each region of the globe based on the same basic lending model. The World Bank is lending more to developing country governments today than it ever has. Yet, if we consider all external financial flows to developing country governments, it appears that the bank matters a lot to a very small number countries (the very poorest on a per capita basis) and not very much at all to most developing countries, including many with significant poor populations. Nonetheless, because of the ability to offer grants and concessional financing, the World Bank also matters increasingly when it comes to key global issues like pandemic response and climate finance, public challenges that are not attractive to private finance.

Despite its longevity and robustness by some measures, the World Bank faces critical challenges today. First, the bank is struggling to adapt its financial and operational model to address global crises even as it continues to provide traditional development finance to client governments. And second, a direct threat to stable governance arrangements looms, the result of a deteriorating bilateral relationship between the United States and China. As the two leading countries across the MDBs, how the US and China choose to engage with each other and with the World Bank itself will help determine how effectively the bank can adapt and grow to meet pressing global needs. For these two countries and their allies, the choice is between development cooperation through the World Bank and competition through a rising wave of bilateral initiatives, a field that China currently dominates through its Belt and Road initiative and broader array of overseas financing.

The next decade will be characterized by these two key transitions for the World Bank. One relates to evolving financing needs, pitting the demands of the bank’s developing country client governments against an emerging global public goods agenda. The other relates to the role of shareholders in the institution and the degree to which a nominally dynamic shareholding model can evolve in practice. The ability of the bank to adjust its financial and operational model to respond to a dynamic global environment, striking an appropriate balance between country demands and global goods, will depend on the ability of its shareholding structure to evolve in the face of some of these same global dynamics. In managing these two transitions, the behaviour of today’s ‘great powers’, the United States and China, will be key.

II. A transitional moment for the World Bank’s financing and operational model

In the years just prior to the collapse of Lehman Brothers, a period of confidence about the economic trajectory of developing countries, some were calling for the end of the World Bank, or at least a substantial part of its financing activities in the face of vanishing need (Lerrick, 2006; Will, 2007). A shrinking number of low-income countries were dependent on the bank for concessional financing, and the World Bank’s middle-income clients were curtailing their borrowing as commercial financing became more attractive. Once-poor economies were now characterized by expanding domestic capital markets, rising external private flows, and governments with access to external bond markets on reasonable terms. Of course, private sources of finance were still nascent in many developing countries, and fragile and/or erratic in many more. But overall, vastly more private capital, including external sources of private capital, was being invested in developing country economies and available to developing country governments compared to prior decades.

This picture more than anything else made the role of the MDBs’ ‘official’ finance appear largely inconsequential by the mid-2000s. Compared to an earlier era when most developing countries were substantially dependent on MDB financing to meet their hard currency financing needs, the picture just before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) pointed to a remarkably different future, one in which official financial flows from multilateral lenders would largely disappear.

The crisis changed that outlook, driving developing country governments back to the World Bank, alongside the IMF and other MDBs, to meet fiscal needs as private capital retreated. Yet, even as market financing returned and countries recovered from the crisis, demand for MDB financing remained at elevated levels and talk of the end of the World Bank dissipated.

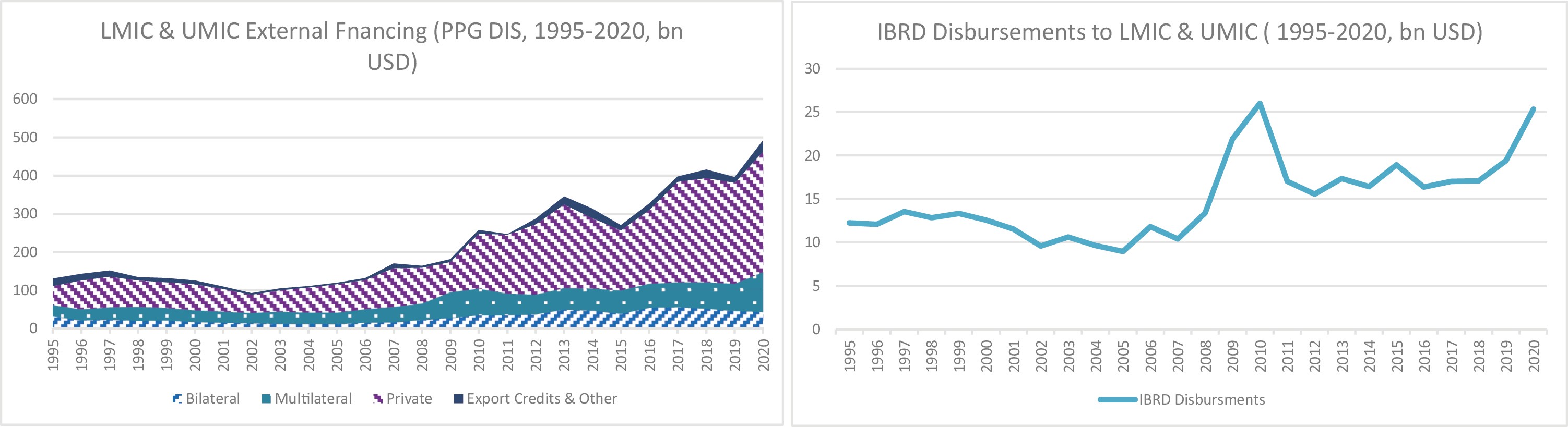

The behaviour of the bank’s client governments during the post-GFC period demonstrates an evolution in their attitudes toward the institution. Many of them didn’t necessarily need MDB financing any more, but they weren’t prepared to abandon it either, particularly with the recent crisis experience fresh in their minds. In 2007, prior to the crisis, the World Bank disbursed just $10 billion to client governments, with new commitments of just under $25 billion per annum (The World Bank Group, 2008). By 2019, prior to the next crisis wave, disbursements had doubled, and new commitments increased to $45 billion (The World Bank Group, 2020a). The 2010s marked a re-embrace of the World Bank by its client governments and at a time when these governments were also enjoying greater access to commercial financing. Private financing for middle- and upper-middle-income developing country governments grew from $100 billion in disbursements in 2007 to over $260 billion in 2019.

Figure 1. IBRD disbursements to MICs and MIC external financing by creditor type, 1995–2020.

The renewed demand for World Bank financing reflected a broader shift toward greater ambition for the institution among its borrowing and non-borrowing shareholders, best exemplified by support in 2018 for a bigger bank from China (the bank’s largest developing country member) and the United States (the bank’s largest shareholder). In the decade following the GFC, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) would enjoy two capital increases (in 2010 and 2018) out of just six in total in the 75-year history of the institution, and the International Development Association (or IDA, the bank’s concessional financing arm) would see record levels of financial mobilization.

However, renewed ambition was not uniformly motivated, and it became clear that the rationale for a larger World Bank fell into two distinct camps. The traditional view held by the bank’s borrowing countries sought to protect the existing lending model, and their central role in it. Consistent with the bank’s founding blueprint, developing country governments would continue to borrow from the institution to meet their development finance needs and would decide on the uses of those funds according to their national priorities. The borrowing countries sought to protect this arrangement as they eyed an uncertain future following the GFC. A benign global interest rate environment would not last forever and developing country finance ministers wanted access to a larger pool of capital from the World Bank in order to finance large infrastructure projects, social programmes, and as a backstop for future crises.

But an emerging rationale offered by the non-borrowing members sought to elevate global public goods within the bank. These countries did not see a rationale for growth in traditional lending outside of the poorest and most fragile countries, but they became increasingly enthusiastic about a new rationale for spending the World Bank’s money. The emerging case for (global public goods) GPGs at the World Bank has been dominated by the climate agenda, but the COVID pandemic has amply demonstrated the need for financing to prepare for and respond to global pandemics. The two issues together have rallied the bank’s wealthy shareholders behind a new mandate for the institution, one that would put global issues alongside country-level demands.

Remarks from US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen in October 2021 encapsulate this view. In addition to promoting the World Bank’s role in pandemic response and climate change, Yellen warns that ‘[i]t is critical that the World Bank continue to manage its resources prudently, judiciously allocating resources to those countries that need it the most while implementing its graduation policy’ (Yellen, 2021). The emphasis on prioritizing the GPG agenda has been consistent across Yellen’s statements before the World Bank’s Development Committee in 2021 and 2022, and she has been joined by leading European shareholders.

A global public goods agenda for the World Bank requires, inter alia, a reconsideration of the traditional use of donor-provided grants within the institution, along with the use of bank profits, allowing for uses beyond loan subsidies aimed at easing the financing terms faced by developing country governments. Relying on trust funds and administrative budgets, the bank today plays a limited role in the provision of GPGs by subsidizing green infrastructure, financing data collection and economic research, and providing limited support for other regional and global entities (e.g. COVAX during the current pandemic).

The World Bank is already the leading multilateral source of climate finance for developing economies, allocating about $20 billion annually (The World Bank Group, 2021). But much of this financing is only modestly subsidized through the IBRD, and total climate financing for developing countries remains substantially short of the $100 billion p.a. target set over a decade ago (OECD, 2020a). If the bank is to continue to be a favoured climate finance institution, overall volumes and levels of concessionality will need to grow, straining the institution’s capital and grants.

Further, the pandemic has tasked the World Bank with another new mandate, sharing similar GPG characteristics. Effective pandemic preparedness and response generates externalities that cannot be fully captured by each of the World Bank’s client countries, and as a result they will underinvest in these activities absent significant volumes of subsidized financing. Wealthy countries, which stand to benefit from the externalities associated with health investments in poorer countries, are increasingly looking to the World Bank to provide the necessary financial incentives. Together, global climate and global health-related investments represent major new mandates for the institution.

Implicit in the case for GPG financing is the need for the World Bank to grapple with the longstanding centrality of client country demand and the core principle of country-led developing finance. If national governments themselves underinvest in activities where benefits may accrue beyond their borders (pandemic response, climate mitigation), then it follows that they will also ‘under borrow’ for these purposes at the MDBs in favour of public goods that mostly serve national interests. Yet, country-driven financing has long been viewed as a virtue of the World Bank and an important counterweight to the heavy hand of donor-driven bilateral aid. Wrestling with this dilemma will be a leading strategic challenge for the World Bank in the decade ahead.[1]

Resolving conflicting positions between non-borrowing shareholders, who wish to direct a growing share of the bank’s resources to GPGs, and borrowing shareholders, who wish to preserve their prerogative to borrow from the World Bank according to national priorities, is made more acute by the challenging environment facing many of these borrowing governments today. Just as the pandemic pointed to the need for proactive efforts to prepare for global health emergencies, it also made clear that developing countries now face broader social and economic harms as a result of the health crisis and are ill prepared to mount an adequate fiscal response.

Evidence from 2020 suggests that most high-income countries effectively counteracted the economic losses from the pandemic with fiscal stimulus. Estimated average GDP losses of just under 7 per cent were offset by fiscal stimulus of 4.5 per cent. In contrast, low- and low-middle-income countries saw GDP losses of 6 per cent and 10 per cent, respectively, yet could only muster fiscal responses equivalent to about 2 per cent of GDP on average (Morris et al., 2021a).

The on-going economic effects of the crisis have been exacerbated by the debt outlook for these countries. Rising global interest rates are increasing the cost of borrowing for developing country governments and in some cases limiting access to bond markets altogether (Gill, 2020). As a result, these countries are increasingly constrained in tapping new financing and are seeing a rise in debt service payments on existing debt.

Both effects are severely constraining fiscal policy. As a result, a growing number of developing country governments, both the poorest, who borrow from the World Bank’s concessional finance window, and those who borrow from IBRD on non-concessional terms, are likely to seek their maximum allocations of financing from the World Bank in the years ahead. In turn, they will be less interested in channelling more of the bank’s resources away from this function or otherwise allow greater earmarking of their borrowing for purposes other than nationally defined spending priorities, which might, for example, include fossil fuel investments over clean energy, or areas of health spending other than direct pandemic response.

And it is not only a matter of developing country preferences. With a larger number of World Bank borrowers in debt distress or at high risk of distress, the operational rules of the bank automatically adjust allocations from loans to grants, putting additional strain on the bank’s resources. In 2015, 30 per cent of IDA countries were at high risk of debt distress and therefore eligible for grants-only assistance from IDA (The World Bank Group, 2018). Today, over half of IDA countries are grants-only recipients (International Monetary Fund, 2022).

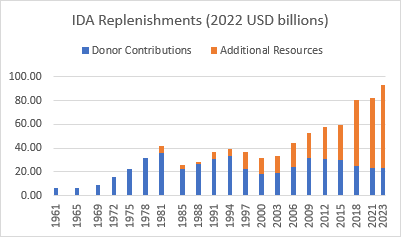

These difficult dynamics within the World Bank are made more so to the degree the bank’s resources are static. With two IBRD capital infusions in the past decade and record-setting replenishments of IDA, the prevailing sentiment among shareholders may be that the bigger bank agenda has reached its limit. Even as IDA’s overall resources have expanded, driven by market borrowing and loan revenues, donor contributions have declined, from a 2010 peak of $31 billion to $23 billion in the 2021 replenishment.[2]

Figure 2. IDA replenishments (2022 USD billions).

With a view that the resource envelope is fixed, reflected in Secretary Yellen’s remarks, the trade-off between country-directed financing and GPG-directed financing is acute. In turn, an expansion of the bank’s overall resource envelope would ease this trade-off and the attendant political tensions among borrowing and non-borrowing shareholders. The possibility for further ambition for the World Bank in this decade, following the expansions of the 2010s, depends on the attitudes of the bank’s largest shareholders, and none more so than the United States and China.

III. Shareholders’ choices between bilateral and multilateral finance

Support for the World Bank typically comes from the foreign assistance budgets of shareholder governments, which entails a choice between bilateral and multilateral allocations. Not surprisingly, most countries favour bilateral channels and the direct control they provide. OECD countries allocate 60 per cent of aid through bilateral programmes on average and 40 per cent through multilateral institutions and funds, a proportion that has remained stable over the past decade (OECD, 2020b).

Whether this relationship continues to hold is questionable, given the rising ‘competition’ framework for foreign aid. Seven years after its launch, China’s Belt & Road initiative is now garnering a more concerted response from Western governments. The announcement by G7 leaders that they will mobilize $600 billion to invest in developing countries is touted by the G7 countries as their response to China’s dominance in global infrastructure investment.

The G7’s Global Infrastructure Partnership (GIP) lacks detail but appears to rely on both bilateral and multilateral channels. To the degree the World Bank is embraced as a partner, the notion that the partnership will compete with China is misguided. Chinese construction firms consistently dominate World Bank procurement, so to the degree the GIP is counting World Bank lending, China is less a competitor than a beneficiary (Morris et al., 2021b).

While the rhetorical framing of the initiative may be confused, the political motivation is clear and almost certainly will favour bilateral channels. If competition is understood in a commercial sense, then the United States and other G7 countries are seeking to advantage their firms over Chinese competitors, relying on bilateral export credit agencies and other forms of financing tied to domestic firms. The World Bank and its open and non-tied procurement procedures will prove to be a poor choice for this sort of competition. In this environment, it appears likely that Western governments will rely more on bilateral agencies going forward. China, in turn, has been increasing its multilateral contributions, but these contributions remain a small share of overall aid and other official finance. For example, China’s cumulative contributions to the World Bank’s concessional finance window totalled just over $2 billion, compared to total Chinese official credits outstanding estimated at $350 billion (Horn et al., 2019; Morris et al., 2021b).

Greater provision of bilateral finance relative to the World Bank and other multilateral channels carries risks for developing countries. Where the World Bank’s mandate is focused on the development progress of poorer countries, official bilateral finance typically has multiple mandates. For example, much of China’s Belt and Road initiative is supported by the Chinese export credit agency (ECA), and like other ECAs, including those of the G7 countries, financing is provided to support the exports of domestic firms. Financing terms can be significantly less concessional than World Bank terms, and competing mandates can lead to financing that is not in the best interest of the developing country borrower. China’s energy-related financing represents an extreme case, with evidence that official development finance has helped to export Chinese coal capacity in order to help ease the green transition within China (Li et al., 2022).

It is conceivable that resources provided to the World Bank by shareholders could increase even as the overall provision to multilateral channels declines. But the evidence for this is mixed. When it comes to MDB capital, the World Bank has declined relative to the other MDBs over the past decade, as capital contributions in the early 2010s favoured the regional MDBs (Morris and Gleave, 2015). Yet, when it comes to donor-provided concessional resources, IDA has grown more dominant relative to other MDBs, even as donor contributions to IDA have declined in absolute terms.

On balance, it appears unlikely that World Bank shareholders will support a significant expansion of the bank’s resource envelope, exacerbating tensions among shareholder groups over priority uses of these funds. To the degree there is scope for change, it rests with the governance of the bank and the unique roles that the United States and China play.

IV. US and Chinese attitudes toward the World Bank

As the primary architect of the World Bank at the 1944 Bretton Woods conference, the US government pursued a shareholding structure that favoured the largest economies, cementing the US position as largest shareholder throughout the history of the institution. Informally over the years, the US also worked to ensure the president of the bank was always nominated by the US government. And of course, the bank is headquartered in Washington, DC, the capital of the United States. In these ways, the World Bank is viewed by many of its shareholders as an American institution.

Yet, US support for the bank has ebbed and flowed over the years. From a time when every US president personally welcomed World Bank delegates to Washington, no president has performed this ceremonial role since President Bill Clinton (Morris, 2016). And from a position as IDA’s largest donor, US contributions have become more erratic over the past decade.

Nonetheless, US leadership continues to be essential to any significant strategic decision in the institution, whether the choice to pursue a capital increase from shareholders or to pursue a multi-billion-dollar trust fund to prepare for future pandemics. Although US shareholding (just under 16 per cent of voting shares) isn’t sufficient to block most decisions, the US position exerts extraordinary influence over a wide array of issues.

Considering this uniquely held position by the United States, which tends to overshadow all other countries, it might not be obvious that China plays its own unique role within the World Bank. Although the lack of progress on shareholding reform (see section V) has kept China as the third largest shareholder behind Japan, it also exercises influence as a major borrower and in turn the largest voice for the bank’s borrowers. Further, Chinese firms are dominant when it comes to procurement contracts at the institution (Morris et al., 2021b). World Bank procurement rules favour the lowest bidders, and China’s state-owned enterprises often prevail when it comes to the bank’s infrastructure financing. Finally, China’s role as a major IDA donor has been cemented through rapid increase in financial contributions over the past decade, rising from the 20th largest donor to the 6th (ibid.).

China’s sustained borrowing from the institution, from the time of its graduation from IDA in 1999 through 2018 when it was the IBRD’s largest borrower, reflects the extraordinary degree to which Chinese officials value the bank’s engagement. Chinese leadership relied on World Bank expertise during the ‘Opening Up’ period and have consistently credited the bank for a playing an important role in the country’s remarkable trajectory of economic growth and poverty reduction (Freije-Rodriguez et al., 2019). When it came time to choose a founding president for the Chinese-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, China put forward Jin Liqun, a veteran of the World Bank and Asian Development Bank, who in turn relied on other World Bank veterans to help write the rules of the new MDB (Lichtenstein, 2018).

Despite China’s interest in maintaining its status as the World Bank’s most important borrower, the United States and other non-borrowing shareholders grew increasingly intolerant of the bank’s loans to the world’s second largest economy, and the 2018 capital increase included agreement that the bank’s largest borrower would dramatically reduce its new borrowing under new rules to limit lending to higher income IBRD countries (Lawder, 2018). Nonetheless, China remains an active and vocal shareholder. And as such, it has been a consistent advocate for a bigger institution via shareholder-provided capital increases.

Increasingly though, the attitudes of the United States and China to the World Bank are tied to their attitudes toward each other. And as the bilateral relationship grows more adversarial, the position of the World Bank becomes more precarious. Nowhere are these tensions better encapsulated than in negotiations around shareholding reform, the process by which the institution reallocates voting shares to account for varying rates of economic growth among its member countries.

V. The failure of governance reform and its lasting consequences

If the 2018 capital increase pointed to a more ambitious World Bank, and one poised to take on a GPG agenda, it also revealed fault lines in the governance of the institution, which now threaten to undermine this ambition. Negotiations in 2018 failed to make substantial progress on shareholding reform, allowing the gulf to widen between actual shareholding among countries and what the countries themselves have agreed to do in principle.

A durable legacy of the Bretton Woods conference was a model of governance for the World Bank that differentiated ownership shares among countries according to economic weight. Even as the newly formed United Nations embraced ‘one country one vote’, the World Bank embraced a shareholding model of governance, with the allocation of shares set roughly according to the economic size of the member government. In practice, this meant the institution, whose mandate was to meet financing needs in developing countries, was governed for many years almost exclusively by non-developing country governments. The bank drew a clear line between ‘borrowing’ and ‘non-borrowing’ member countries, such that developing countries enjoyed the privileges of accessing the bank’s financing and the rich countries enjoyed the privilege of determining every aspect of how the financing would be accessed, including policy conditions on loans.

Over time, as developing economies grew, so did their relative shareholding in the World Bank. In 1950, wealthy countries controlled 80 per cent of the voting shares of the IBRD. Through successive rounds of shareholding reform, developing country governments today hold shareholding equal to that of their wealthy country counterparts (The World Bank Group, 2022). This trend coincided with an operational shift toward a ‘country ownership’ model of financing that, at least rhetorically, sought to defer to the wishes and priorities of the borrowing government.

The bank’s shareholders play a hands-on role in the institution, affecting the daily operations of the bank in the form of a resident board of directors, who must approve or otherwise provide oversight for virtually all the bank’s operations. Shareholder governance matters most when it comes to strategic issues, particularly those that point to structural changes in the bank, such as the creation of IDA or the International Finance Corporation (IFC).

Governance tensions in the World Bank have arisen in specific country cases as much as across broad groupings of countries, and none more so than the case of China in recent years. Governance reform is a zero-sum game. For one country to gain relative shareholding power, another country must lose. No country wishes to cede relative shareholding, particularly not a country that may already be feeling the indignity of declining economic power. Given these dynamics, progress depends on a reform champion to play the role of honest broker.

When it comes to relative gains for China and losses for European countries, the United States has played this role, or at least it did until 2018. China’s rapid economic growth of the past two decades has placed consistent pressure on shareholding reform at the World Bank, just as it has at the IMF. And the United States through much of this period has been a consistent advocate, not for China per se, but for the core principle that ties shareholding to economic weight. The US government could afford to play this role generally because of the sustained US economic power, which meant there was no threat the United States would lose shareholding under any reform scenario.

The shareholding formula adopted by the bank’s member governments has evolved over time to incorporate IDA contributions as a supplementary measure, while still relying predominately on economic size. Importantly, this formula is not adopted mechanistically. It is used to articulate and quantify the core principles of shareholding in the bank and to signal that shareholding should adjust over time. But the outcome of shareholding reform is the result of difficult negotiation among the bank’s member governments, and shareholding principles that are readily agreed to by all in the abstract prove difficult to implement. As a result, there has been a growing cleavage between the numbers specified by the formula and the outcome of negotiations.

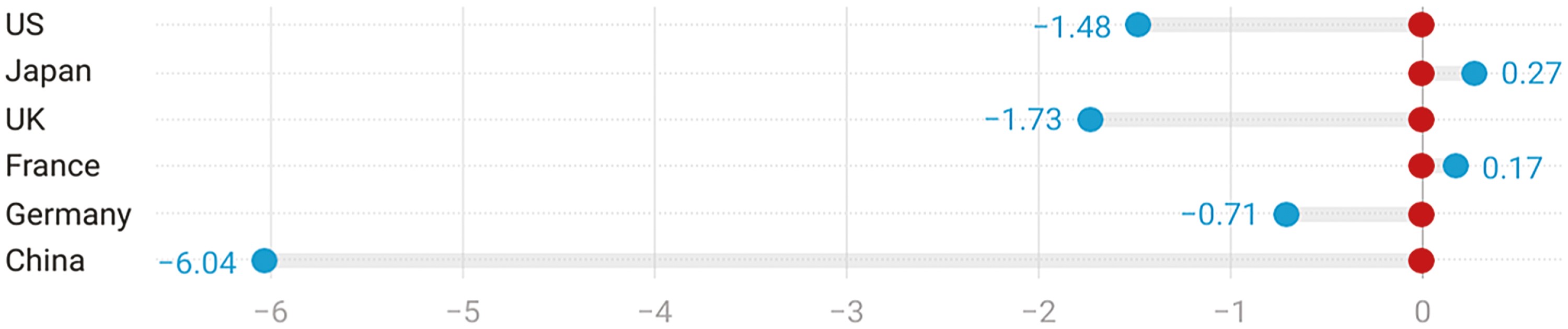

Never has this gulf been so great as it is with China today. According to the agreed formula, China should have held 12 per cent of the bank’s shares in 2018, yet it rose to just 6 per cent as a result of the shareholding reforms that year (Development Committee, 2020). China’s misalignment alone is comparable in scale to the entirety of Japan’s current IBRD shareholding. The lack of substantial progress on China’s misalignment no doubt reflected in part a change in stance by the United States vis-à-vis China. Whereas the US government as recently as 2010 was China’s advocate in the shareholding reform process, a hardening in geopolitical positions by 2018 meant the United States was no longer willing to support a significantly larger Chinese stake at the World Bank, let alone be a champion for that outcome.[3]

Figure 3. IBRD voting power misalignment among top shareholders (absolute diff. in % pts).

Source: Development Committee (2020).

The Chinese government has registered its unhappiness with the state of its shareholding. Finance Minister Kun Liu in 2021 indicated that China was ‘deeply disappointed’ and attributed the lack of progress to ‘political factors’ that are undermining the legitimacy of the institution (Liu, 2021).

The more contentious US–China dynamic that has manifest in the shareholding discussions is important for governance and strategic direction in the institution more generally. The World Bank derives considerable strength from its multilateral character, reflected in the participation of 188 member countries. Yet, the governance model indicates that the biggest countries matter the most, and no two individual countries matter more to the bank today than the United States and China, the former as the largest shareholder and the latter as the frustrated third-largest shareholder. The failure of shareholding reform could represent a growing barrier to cooperation in the years ahead, where cooperation is most needed between these two countries, both inside and outside the bank, in the face of today’s global challenges.

VI. The choice to cooperate

The US aim to compete with China in the developing world seems set. It has emerged as an organizing principle across the US aid architecture and now features prominently in the G7’s agenda. The remaining question is whether competition between the US and China will also play out within the World Bank and other multilateral institutions. Yet, the very notion of competition within the bank raises challenging issues for the United States. Would the United States seek to block additional shareholding for China, despite shaping the very principles that demand it? Would the United States discourage further growth in China’s financial contributions to the bank, despite a desire for greater burden sharing among donors? Would the United States seek to block World Bank contracts to Chinese firms despite shaping the procurement rules under which China has become dominant?

Given the rapid deterioration in the bilateral relationship, any or all of these positions now appear plausible. It is more challenging still to consider what it would take to shift US policy toward a more cooperative stance, in line with the shareholding principles of the institution. And if gains in shareholding is the prize for China, such that the country rises to the position of second largest shareholder, it is worth considering what the US might demand in exchange for its support.

First, the United States could seek agreement from China to favour the bank’s core financing mechanisms over earmarked contributions that favour Chinese firms. China has provided large trust fund contributions to the MDBs with funding earmarked for infrastructure development, which encompasses sectors in which Chinese firms are dominant (Morris et al., 2021b). This earmarking has the effect of channelling more MDB financing to Chinese construction firms. The bank’s interests, and secondarily US interests, would be better served by unearmarked contributions. This mostly means recommitting to growing contributions to IDA, whose priorities are set collectively by IDA donors and IDA aid recipients. After a period of rapid growth, China’s contributions to IDA grew only slightly in the 2021 replenishment cycle (Executive Directors of IDA, 2022). Consistent with ascending to the position of second largest shareholder in the World Bank, China should target a leading donor position with IDA.

Second, the United States could seek greater Chinese support for GPGs at the bank, in cases where earmarking on behalf of this agenda serves this broader interest. In addition to mainstreaming climate and pandemic preparedness into World Bank financing, the United States has also sought greater support among donors for World Bank trust funds—both the Climate Investment Funds and the new trust fund for Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness and Response. To date, China has not committed to the climate funds, though it has made an initial contribution to the pandemic fund.

Finally, the United States could seek Chinese commitments related to the norms and standards that guide World Bank operations. This would entail some rethinking of the bank’s role to something akin to the IMF’s surveillance mandate, which generally does not distinguish between ‘borrowing’ and ‘non-borrowing’ members. The World Bank is guided by core standards in debt sustainability, procurement competition and transparency, and environmental and social safeguards. These standards are operational for the bank itself and also serve as the benchmark standard for all development finance.

Yet, the bank itself lacks a direct basis for demanding adherence to these norms among its shareholders when it comes to their bilateral activities. As a result, its efforts to date have been muted. For example, under the World Bank’s new sustainable financing policy, the institution commits to more aggressive ‘outreach’ to relevant creditors to ensure their behaviour is consistent with debt sustainability for the World Bank’s client governments (The World Bank Group, 2020b). Yet the bank plays no role in seeking or enforcing rules that would bind the behaviour of bilateral creditors.

China’s official finance to date has been deficient in each of these areas. Inadequate standards for sustainable lending (both lending terms and volumes) have contributed to debt distress in many vulnerable countries. And an approach that relies on local environmental and social standards has produced substantially worse outcomes compared to World Bank projects (Yang and Ray, 2021).

The World Bank already plays an informal role as norm setter when it comes to global development finance. But the areas in which bank rules help to set informal benchmarks could usefully be leveraged to bind bilateral creditors more formally. This sort of role could be amplified with US backing and steered toward Chinese commitments. The China Development Bank and China Exim Bank now rival the World Bank in the scale of financing in many developing countries. An effort to align the behaviour of these bilateral lenders with the World Bank could yield significant gains in areas the United States has defined as priority concerns: debt risks; environmental impacts; and transparent and competitive procurement.

Pursuing this agenda with the Chinese would imply mutual commitments to align bilateral behaviour with World Bank standards. The commitment to pursue this path could be struck bilaterally between the United States and China, while the agenda itself would seek to encompass all member countries. While China may represent an extreme case in many of these areas, the lack of agreed standards across bilateral lenders has meant generally poorer standards across all bilateral agencies relative to the World Bank. For example, none of the G7 countries achieves the level of disclosure and contract transparency that is the norm for the bank and other MDBs, the consequence of which is more difficult resolutions of debt distress across a growing number of developing countries (Gelpern et al., 2021).

Whether the United States seeks to engage China on these issues depends on its commitment to keeping China in the tent of the World Bank. To date, China has expanded its support for the institution through IDA contributions, trust funds, and support for capital increases, even as it has expanded its development finance bilaterally (the Belt and Road initiative) and through new multilateral initiatives (the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the New Development Banks). But the pace of China’s World Bank commitments, evidenced by its most recent IDA commitment, has slowed and China’s borrowing from the institution has declined markedly, under pressure from the United States and other shareholders. Bilateral initiatives like Belt and Road and multilateral channels like AIIB are not direct substitutes for full engagement in the World Bank. Nonetheless, it is uncertain whether China will increasingly see them as alternative options and whether the United States will actively encourage that thinking by its own stance toward China within the World Bank.

VII. Conclusion

The devastating toll of the 2020 global pandemic has coincided with a period in which the destructive effects of climate change have been made increasingly visible around the world. Together, these events have forced the World Bank’s shareholders to confront an institution that is both central to, and ill-suited to, the task of marshalling a financing response. Central because no other global institution has the capital base, public mission, and assembled expertise. But also ill-suited because the longstanding operational model is biased against the provision of global public goods at scale.

Making appropriate adjustments to the bank’s operational and financial model is made more difficult by the implicit trade-offs. More financing in support of a new mandate implies less money for existing activities, absent agreement to expand the overall resource envelope. Grappling with these issues points to the need for structure rather than incremental change. Yet, the governance of the bank that will be tasked with these decisions is currently confronting its own dilemma—how to accommodate a rising shareholder in the face of conflict between leading shareholders.

The hopeful path would see the United States, as the bank’s largest shareholder, and China, as the rising number two, embrace the cooperative model that today’s global challenges require. From this orientation, a bilateral agreement can be struck between the two that respects each country’s interests and positions the World Bank for a more ambitious future.

The paper was made possible by support from the Ford Foundation and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. I would like to thank Rowan Rockafellow and Rakan Aboneaaj for their research assistance and reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

[1] In turn, a shift toward GPGs implies significant reorganization of bank activities and staff, with less emphasis on country teams. This organizational structure is deeply embedded in the institution, even after significant reorganization efforts in recent years.

[2] Growth in IDA’s resources has come from repayments on prior loans by IDA’s borrowers and the 2018 decision for IDA to begin issuing bonds in commercial markets.

[3] See US Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner’s endorsement of shareholding reform in his 2010 Development Committee statement (Geithner, 2010).

References

Development Committee (2020), ‘2020 Shareholding Review: Report to Governors at the Annual Meetings’, Washington, DC, The World Bank Group. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

Executive Directors of IDA (2022), ‘Additions to IDA Resources: Twentieth Replenishment Building Back Better from the Crisis: Toward a Green, Resilient and Inclusive Future’, Washington, DC, The World Bank Group. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

Freije-Rodriguez, S., Hofman, B., and Johnston, L. (2019), ‘China’s Economic Reforms, Poverty Reduction, and the Role of the World Bank’, Singapore, East Asian Institute. Google Scholar CrossrefGoogle Preview WorldCat COPAC

Geithner, T. F. (2010), ‘Statement by Secretary Timothy F. Geithner at the Development Committee (DC) Meeting’, Washington, DC, US Department of the Treasury. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

Gelpern, A., Horn, S., Morris, S., Parks, B., and Trebesch, C. (2021), How China Lends: A Rare Look into 100 Debt Contracts with Foreign Governments, Washington, DC, Center for Global Development. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

Gill, I. (2020), ‘Developing Countries Face a Rough Ride as Global Interest Rates Rise’, Washington, DC, Brookings Institution. Google Scholar

Horn, S., Reinhart, C., Trebesch, C. (2019), ‘China’s Overseas Lending’, NBER Working Paper 26050, Cambridge, MA. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

International Monetary Fund (2022), ‘List of LIC DSAs for PRGT Eligible Countries as of May 31, 2022’, Washington, DC, International Monetary Fund. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

OECD (2020a), ‘Climate Finance for Developing Countries Rose to USD 78.9 billion in 2018’, Paris, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

—(2020b), ‘Overview’, in OECD, Multilateral Development Finance 2020, Paris, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

Lawder, D. (2018), ‘World Bank Shareholders Back $13 Billion Capital Increase’, Reuters. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

Lerrick, A. (2006), ‘Has the World Bank Lost Control?’, in N. Birdsall (ed.), Rescuing the World Bank: A CGD Working Group Report & Selected Essays, Washington, DC, Center for Global Development. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

Li, Z., Gallagher, K., Chen, X., Yuan, J., and Mauzerall, D. L. (2022), ‘Pushing Out Or Pulling In? The Determinants of Chinese Energy Finance in Developing Countries’, Energy Research & Social Justice, 86(1), 102441. Google Scholar WorldCat

Lichtenstein, N. (2018), A Comparative Guide to the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Oxford, Oxford University Press. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

Liu, K., (2021). ‘Statement by H.E. Ken Liu Minister of Finance on Behalf of People’s Republic of China 104th Meeting of the Development Committee’, Washington, DC, The World Bank Group. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

Morris, S. (2016), ‘Responding to AIIB US Leadership at the Multilateral Development Banks in a New Era’, Council on Foreign Relations Discussion Paper. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

—Gleave, M. (2015), ‘The World Bank at 75’, Washington, DC, Center for Global Development. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

—Sandefur, J., and Yang, G. (2021a), ‘Tracking the Scale and Speed of the World Bank’s COVID Response: April 2021 Update’, Washington, DC, Center for Global Development. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

—Rockafellow, R., and Rose, S., (2021b), Mapping China’s Multilateralism: A Data Survey of China’s Participation in Multilateral Development Institutions and Funds, Washington, DC, Center for Global Development. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

The World Bank Group (2008), ‘The World Bank Annual Report 2008’, Washington, DC, The World Bank Group. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

—(2018), ‘Debt Vulnerabilities in IDA Countries’, International Development Association, Washington, DC, The World Bank Group. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

—(2020a), ‘Supporting Countries in Unprecedented Times: Annual Report 2020’, Washington, DC, The World Bank Group. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

—(2020b), Sustainable Development Finance Policy of the International Development Association, Washington, DC, The World Bank Group. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

—(2021), ‘World Bank Group Climate Change Action Plan 2021-2025: Supporting Green, Resilient, and Inclusive Development’, Washington, DC, The World Bank Group. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

—(2022), ‘IBRD Subscriptions and Voting Power of Member Countries, March 2022’, Washington, DC, The World Bank Group. Google Scholar

Will, G. F. (2007), ‘The Real World Bank Problem’, Washington, DC, The Washington Post, 10 May. Google Scholar WorldCat

Yang, H., and Ray, R. (2021), ‘How Green and Inclusive is China’s Overseas Development Finance? A New Global Outlook’, Boston, MA, Boston University Global Development Policy Center. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

Yellen, J. L. (2021), ‘Statement from Secretary of the Treasury Janet L. Yellen for the Joint IMFC and Development Committee’, Washington, DC, US Department of the Treasury. Google Scholar Google Preview WorldCat COPAC

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.