Recommended

POLICY PAPERS

WORKING PAPERS

This note was first published in the ID4Africa 2019 Conference Almanac.

Digital ID as a development tool

India has emerged as a leader in building on its biometric digital ID (Aadhaar) to reform service and program delivery. It moved quickly to consolidate the rollout of Aadhaar, and then to embed the unique Aadhaar number into program databases. A range of applications, including digital signature and payments, was then constructed on top of the Aadhaar foundation (the India Stack). Together with partners, the Center for Global Development is analyzing the effects of Aadhaar-based reforms. India offers lessons for many other countries as their focus evolves from rolling out an ID system towards using it to improve the efficiency and inclusivity of service delivery. Some programs using Aadhaar are federally administered but others are implemented at state level. It is already clear that some states and sectors are reforming better than others, generally because of better design of the digital reforms or stronger capacity to implement them. The three programs we discuss below highlight achievements as well as challenges that need to be overcome for greater efficiency and inclusion.

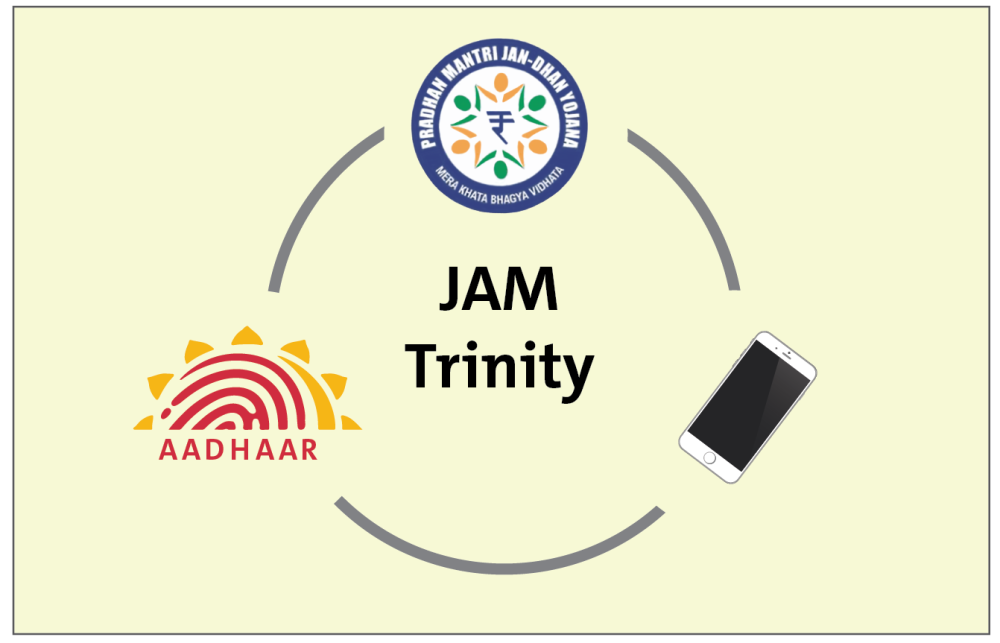

An integrated trinity: the JAM

India recognized early the need to integrate Aadhaar into two other pillars for reform: mobile communications and financial access. The resulting trinity is known as JAM: Jan Dhan (financial inclusion), Aadhaar (biometric ID), and mobile connections. With 1.2 billion unique numbers, Aadhaar now covers about 95 percent of India’s population, including almost all adults. In 2014, the government announced the Jan Dhan program to achieve the goal of universal financial inclusion; by 2017, 82 percent of India’s adult population had access to a bank account, up from 56 percent when the program started. Mobile phone subscriptions increased from 17 per 100 inhabitants in 2007 to 85 in 2016, approaching universal access with a growing share of smartphones and internet-enabled devices.

The JAM trinity brings together three digital transformations and exploits synergies among them. Aadhaar enables customers and banks to easily fulfill know-your-customer (KYC) norms necessary to obtain a bank account or a mobile SIM card, while costs have been further reduced by allowing the possibility of digital or e-KYC. Aadhaar is therefore linked organically to new bank accounts and mobile connections, making them accessible to large sections of the population. In turn, much of the increase in financial access has been spurred by the Aadhaar-based reforms to social programs that routed benefits through bank accounts.

Jan Dhan – Aadhaar – Mobile Trinity

Having substantially bridged the access gap in financial services and mobile services, the JAM approach has facilitated service delivery reforms through:

-

linking Aadhaar with beneficiary databases for public services and subsidies

-

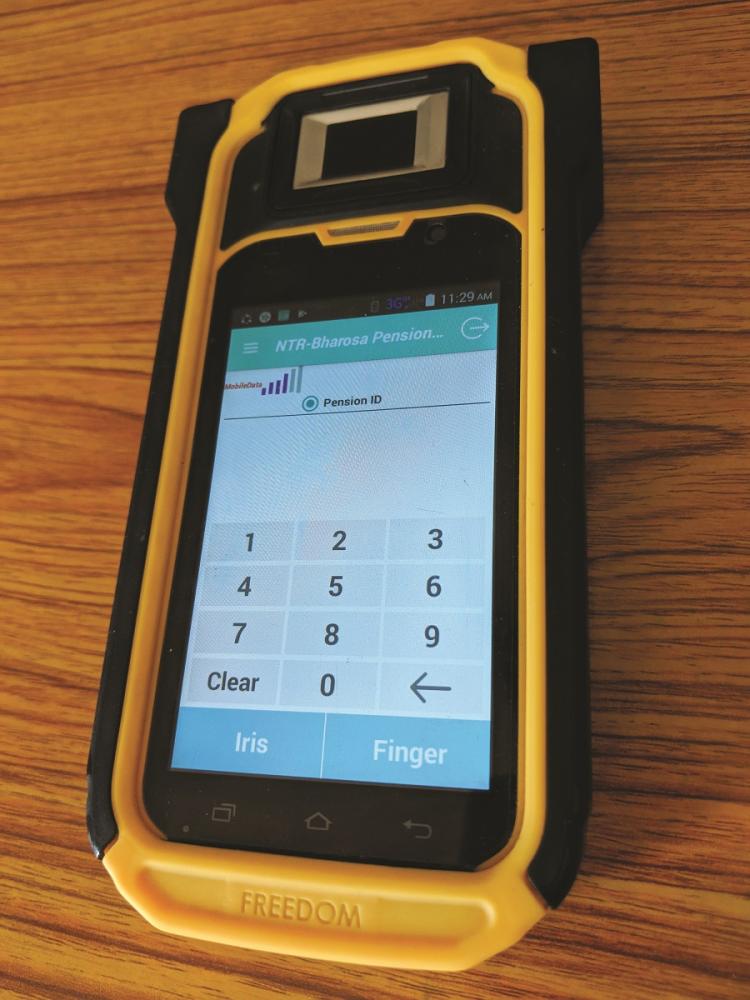

implementing Aadhaar-enabled remote authentication services to verify beneficiaries at the point of service for subsidized food and fertilizers, pensions, and other benefits

-

transferring subsidies and cash directly to beneficiary bank accounts through the Aadhaar Payment Bridge, an interoperable system that uses Aadhaar-linked bank accounts for financial transactions

Concerns over privacy and authentication failure

Before drawing lessons from particular applications, it is essential to flag two policy debates relating to Aadhaar itself.

Aadhaar, together with its managing organization the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI), were introduced by an executive order and in advance of enabling legislation. Partly as a result, and also because India still does not have a law protecting the privacy of sensitive personal data, it has been subject to numerous legal challenges before India’s Supreme Court. Even though Aadhaar collected minimal personal data, the prospect that the unique number could soon be incorporated into individual records of all types—both private and public sector—fanned concern over the impact on privacy. The first Court judgment ruled that Indians did indeed have a right to privacy but that it was not absolute; that privacy needs to be weighed, in individual policy applications, against the State’s interest in effective administration. A second, much-anticipated, Court judgment set out the implications for Aadhaar—its use was authorized in the two specific areas of the administration of government benefits and programs, as well as in tax reporting. While the full import of the ruling is still being worked out, it places Aadhaar into a perhaps similar status as the US Social Security Number, whose use is also restricted to certain purposes by law. The Court’s ruling has set off a further round of debate and innovation, including the introduction of Tokenized Aadhaar (a 16-digit virtual ID number cryptographically derived from the Aadhaar number), a formal Aadhaar Card capable of providing offline authentication for less-demanding applications without disclosing the full number, and commitment to finalizing a data protection law. Aadhaar’s proponents may be correct in that the path of “build first and legislate later” was the only way to move forward in India, but the lessons for other countries is clear: this is a risky approach and is not recommended.

A second, debated, feature of Aadhaar has been its emphasis on online authentication against the central database, particularly using biometrics. Although many people carried an “Aadhaar Card” (before the one mentioned above) this was only a piece of paper with the number and perhaps a picture; it was not used, for example, to authenticate a recipient for a benefit. Many factors can cause online authentication to fail: biometric mismatch, communications failure, or server overload, causing the attempt to time out. Even if all beneficiaries were successfully enrolled in Aadhaar, such frictions could cause legitimate claimants to be excluded from essential benefits or, at least, to suffer serious inconvenience. The UIDAI has been emphatic in stressing that programs and schemes must have protocols to deal with cases of biometric failure and has, indeed, provided for a range of alternative authentication methods, including iris and one-time-passwords sent to a mobile linked to the Aadhaar number. Nevertheless, studies of several programs suggest that adherence to exception-management protocols has been uneven. Beneficiaries have been more likely to face authentication exclusion in some states (Jharkhand appears to be an example) than in others. Even though the 2017–2018 State of Aadhaar report finds that non-Aadhaar factors tend to be a more significant cause of exclusion than those relating to authentication in the three states it surveyed (Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan, and West Bengal), experience with Aadhaar offers an important lesson for other countries—the critical importance of strong policies and protocols for handling cases of technology failure. Some examples emerge from the cases below.

Towards more efficient and equitable subsidies: LPG and PaHaL

India has long suffered from inefficient and inequitable fuel subsidies. For household LPG cylinders, most of the subsidy was captured by higher-income groups, mostly urban residents. Duplicate connections, ghost beneficiaries, and significant diversion of domestic subsidized LPG towards commercial use led to long wait times for genuine beneficiaries. The subsidy also came at a significant fiscal cost and with uncertainty due to volatile international energy prices. The poor were excluded from the LPG distribution network and had to use firewood to cook, leading to severe health problems, especially for women who also had to bear most of the time cost of collecting fuel.

Starting in 2013, the PaHaL program reformed this system. Instead of paying a subsidized price for LPG cylinders, beneficiaries paid the market price and the government transferred the subsidy directly to their bank accounts when they paid the dealer to deliver the cylinder. Payment was confirmed by SMS sent to mobile phones. Customers were empowered – they could track their deliveries, rate their distributors, and change them if dissatisfied.

The program created a clean list of beneficiaries, removing some 25 million false and inactive recipients. Dealers could no longer profit from diverting subsidized cylinders so that wait times for refills ordered by genuine households decreased. The reform also led to fiscal savings, although the quantum is open to debate. With the subsidy individualized to identified people and households, nearly 10 million LPG consumers voluntarily relinquished it through the government’s GiveItUp campaign, and further targeting measures have been taken to gradually shift more of the benefits toward the poor.

It is difficult to link all these outcomes directly to Aadhaar; the first phase of deduplication relied on name and address matching as penetration of the unique ID number had not yet reached saturation. Still, the program now links consumers’ Aadhaars, as well as Aadhaar-linked bank accounts and mobile numbers, to the beneficiary database. Unique identification has been key in the transformation of the subsidy regime. Surveys indicate high rates of customer satisfaction with the changes, particularly because of the greater efficiency of the system.

Building on the success of PaHaL, in 2016 the federal government announced a program (Ujjwala) to provide 50 million poor rural women with LPG connections within three years. The program has been a huge success. Aadhaar is now mandatory to obtain a new LPG connection so new applicants can be checked against existing beneficiary lists to eliminate fraud. Moreover, many of the Jan Dhan accounts were opened by rural women to receive the subsidy.

Empowering women through a social registry: Rajasthan

In 2014, the newly elected government of Rajasthan—a famously patriarchal state in northern India—began building a registry of families who received public subsidies, benefits, and transfers. The Bhamashah program required families to register their members along with their respective Aadhaar numbers and to own an active bank account to receive direct benefit transfers. The government also mandated that a woman had to be designated as the head of the family for benefit purposes. All family cash transfers, such as social pensions, would be delivered to her Aadhaar-linked bank account.

Once families were registered, they could access public benefits, such as food rations through the public distribution system (PDS), social pensions, scholarships, and the cooking gas subsidy. Aadhaar-based biometric authentication at point-of-service was required for PDS benefits.

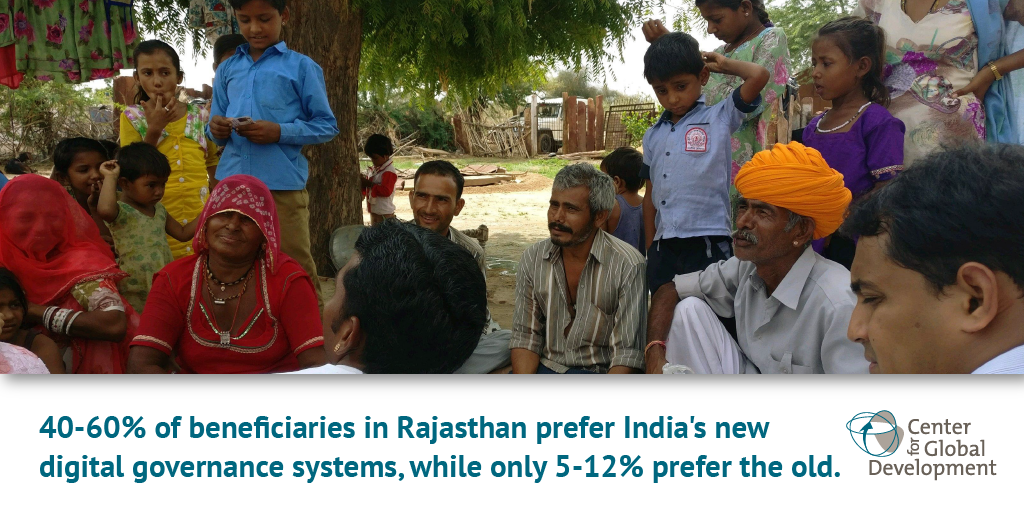

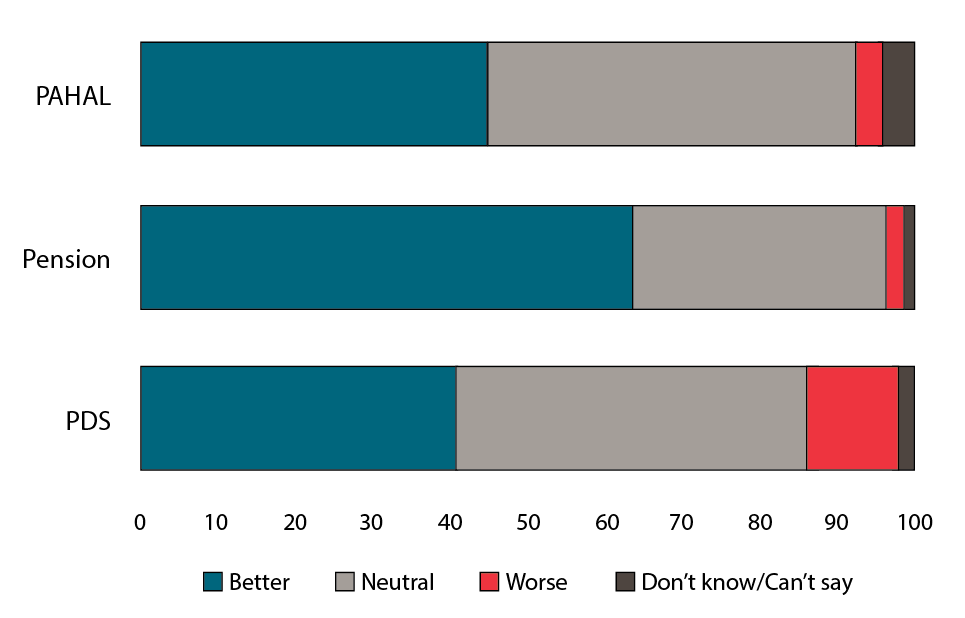

Our household surveys found that most people had positive views of the newly digitized programs. Many felt that they had more control over their entitlements and that there was less corruption in the food and pension distribution systems.

Beneficiary perception of digital service reforms

Our surveys also confirmed a significant improvement in financial inclusion for women. Nearly two-thirds of the women heads of households had to open a new account to comply with the government policy. By the time of the survey, many had started to transact on their accounts, though they were often accompanied by a husband, son or other male family member, usually because of transport difficulties in getting to a bank or because they were not sufficiently literate to undertake financial transactions on their own.

Some cautions from Rajasthan

Our Rajasthan study revealed several problems that countries may face as they transition towards digitalized services.

-

Digitization. Existing databases may not be consistent, and errors in seeding the unique ID number in beneficiary lists can compound the problem, creating aggravations for beneficiaries or even denial of benefits. These difficulties were compounded in Rajasthan by the restructuring of program databases into the Bhamashah registry and by efforts to shrink beneficiary rolls at the same time as they were being digitized.

-

Authentication. As noted above, the reliability of biometric authentication is also a challenge. Fingerprints alone are not enough—they may not always work or work smoothly. Backup methods are needed and, indeed, the Aadhaar approach provides for other options. But sometimes these are not used by frontline service providers, who may ignore protocols and send beneficiaries away to come back another time, or possibly even deny them their benefits. The risk is arguably greatest for the most vulnerable beneficiaries, who have the least capacity to assert their rights before the frontline providers.

-

Digital literacy. Eighty percent of women heads of households cannot read or write text messages or even make a call using mobile phones. While the use of ID to create a social registry can promote inclusion and greater financial access, not everyone will have the necessary tools to participate fully in a digital environment. As these systems mature, bridging the digital capacity gap will be an important issue for the development and technology communities to address.

Digital ID as a foundation for digital governance: Krishna and Andhra Pradesh

Over the last two decades, Andhra Pradesh (AP) state in southern India has promoted a technology-based development strategy. Home to Microsoft and Google, among other tech titans, AP has fostered a culture of innovation within the state government, providing incentive for administrators to try new ideas. Over time, it has built a technically skilled workforce that can help to implement digital reforms rapidly and at scale. Within AP, Krishna District has been a recognized leader in using technology to improve public service delivery.

Aadhaar is the foundation of AP’s digital governance framework. It is integrated into all programs and administrative departments, effectively making it mandatory to receive any public services, subsidies, or transfers. Although AP has not restructured programs around an integrated social registry like Bhamashah, the ubiquitous use of Aadhaar makes every beneficiary and each transaction trackable in real time at the individual level.

Using the power of uniqueness and trackability, AP has introduced portability in the delivery of public services. PDS beneficiaries can obtain food rations from any fair price shop in the state, benefitting migrants who were denied their benefits in the earlier system. Social pension recipients can now collect their benefits from any local government office, reducing travel cost and inconvenience, especially important for the elderly. Customers can “vote with their feet,” making them less vulnerable to exploitation by frontline providers.

While other states, like Rajasthan, also collect real-time data on the delivery of programs, AP has gone beyond digitally recording administrative data to actively building on this data to increase efficiency and accountability and to reduce exclusion. A central hub collates all service delivery data generated through Aadhaar-based transactions in real time, analyzes the data, and provides dashboards for monitoring implementation. The hub also collects information on grievances and tracks their resolution within a specified timeframe. At local levels, each community has a Village Revenue Officer (VRO); these VROs are mandated to deal with the (very few) exceptions and cases of technology failure. They may use other methods of authentication, such as face recognition, when unable to authenticate through regular means and may also vouch for beneficiaries in case all else fails.

As the digital governance system has matured, AP has integrated a rapid, high-frequency feedback mechanism as part of the real-time governance approach. Each beneficiary must agree to be part of a quality survey process and receives a feedback robocall on service quality every time they access a service. In the case of PDS alone, this would imply around 10 million calls per month, covering every fair price shop in the state. Those responding with negative feedback are rolled over to a manual system to register complaints, which must then be resolved within specified periods. The data generated is then analyzed to rank different districts, mandals, and villages, as well as service programs, scoring them on a “happiness index” which is used as a management tool. Feedback can also be used to redesign delivery mechanisms to make them more beneficiary-centric—for example, the most recent shift to deliver pensions through Panchayat offices, which many pensioners find most convenient -- rather than banks.

This combination of real-time feedback and clear human accountability is intended to promote integrity and efficiency at each level of the administration, thereby increasing inclusion and trust in the system. The digital systems also provide flexibility to design, evaluate, and restructure service delivery mechanisms to promote inclusion and increase efficiency.

Does it work? We surveyed beneficiaries and service providers, and conducted focus group meetings. The results show that beneficiaries and service providers generally viewed the Aadhaar-enabled system positively, and that they approved of the government’s digital governance strategy. The picture is not perfect: some respondents express frustration with less-than-smooth biometric authentication at points of service. However, people are able to recognize tradeoffs and judge a reform on the basis of a combination of positive and negative features. For example, 80 percent of the majority who found the new PDS system to be better asserted that rations were no longer diverted, but so did 46 percent of the minority who considered the new system to be worse. Conversely, while 100 percent of those who thought the new system worse considered that authentication failures were frequent, so did 42 percent of the majority who thought that the new system was better. Reforms do not have to be perfect in order to be viewed favorably,

Our results also suggest that the combination of beneficiary choice, real-time feedback loops, and clear accountability for grievance redressal and technology failure has eliminated perceptions of technological exclusion. AP appears to be in the forefront of dealing with this problem, one that will arise for any system seeking to transition to the use of a digital ID system for point-of-service authentication. The findings confirm those of the 2017–18 State of Aadhaar report that exclusion appears to be very rare in AP.

Did AP’s digital reforms produce savings? In contrast to many other reforms, their main stated objective has been to improve service quality rather than to save resources. In common with many other South Indian states, AP maintained, and still maintains, a generous social safety net. Unlike Rajasthan, it did not seek to remove beneficiaries from the rolls as it digitized them, even though it does collect data, through Smart Pulse surveys, that can be used to rationalize beneficiary rolls. We cannot estimate the overall balance of benefits and costs from its digital governance reforms, but they appear to have generated some substantial savings at program level. Estimates for the PDS system put savings on the order of 33 percent of costs, from a combination of eliminating nonexistent beneficiaries and preventing the diversion of subsidized products

Some lessons from India’s experience

India is currently the world’s laboratory in the application of digital ID. Transformation using the JAM strategy is unfolding on a massive scale, in multiple programs and across different states. The lessons are still accumulating, but already they suggest some key takeaways for African countries intending to pursue digital governance reforms based on digital ID.

Rapid roll out facilitates use. The strategy of rapidly rolling out a minimalist but fully digital ID, achieving saturation coverage within a short period, and embedding it rapidly into service delivery programs has advantages. Had India not achieved such high coverage so quickly, it would not have been able to build on Aadhaar to reform subsidies, benefits, and other programs. The rollout has been facilitated by separating the ID from attributes such as proof of nationality that many people would not have been able to provide easily. Rapid take-up also requires an upfront focus on creating an effective authentication ecosystem, an area neglected by some countries as they focus on rolling out the system.

Do not neglect the legislative framework. As described earlier, the path of “build first and legislate later” may have been the only way to go in India, but it is a risky approach and not recommended for other countries.

Exploit the synergies between ID, mobile communication, and financial inclusion. An integrated approach to the entire digital revolution spectrum is critical for inclusive and effective policy design. It is important to understand the strengths of each of the three digital pillars (ID, mobile, and financial services) and to exploit complementarities among them, including in the delivery of programs. This may be particularly important for African countries considering the rapid growth of digital communications and mobile money in that region.

Good program design is essential. The main goal should be to improve the efficiency, equity, and inclusiveness of service delivery. Successful programs seek complementarities among a range of development goals, such as financial inclusion and women’s empowerment. They can also take advantage of the flexibility that digital technology provides to undertake mid-course correction based on data and evidence of impact, as well as to open up choice to beneficiaries over where to receive their services. Fiscal savings should emerge from the design and not be the sole motivator for reform.

Reforms take sustained effort, attention, and political will. At the time of our surveys, AP’s reforms had been pushing forward for at least five years and those in Rajasthan for half that time; reform of the LPG system has also been ongoing over several years. Digitizing databases, embedding ID numbers, and correcting the inevitable errors take time. Even when political will and administrative capacity exists, digitization of service delivery can cause considerable inconvenience for genuine beneficiaries. Success depends on sustaining the effort, ensuring continuity, and demonstrating effectiveness early in the implementation process.

Reshape incentives towards performance. Reforms challenge vested interests who benefited from the previous system. There may be a need to improve incentives along the service supply chain to compensate for less opportunity for fraud and corruption and prevent vested interests from mobilizing against the reforms. In each of the three cases discussed here, service margins were increased (from low levels) to partly compensate for the elimination of opportunities for diversion and corruption. The extensive data generated by digitized delivery systems also makes it more feasible to tailor incentives to service delivery.

Institute clear accountability for grievance redressal. Technology is not infallible. Many individuals have limited capacity to participate in digitized programs, and these are often the most dependent on the benefits they provide. To prevent exclusion, it is essential to have clear protocols for exception management and clear accountability for handling cases of technological failure. The more choice that can be provided to beneficiaries—over alternative providers and also alternative ways to authenticate themselves—the more smoothly the new systems will operate.

Build on administrative data to empower the customers. Digitized service programs, as implemented in India, create vast quantities of administrative data, much in real time. This increases the premium on using the data to improve performance, and also on protecting data. It also offers opportunities to build further on transactions records, to superimpose real-time monitoring and beneficiary service assessments on top of the digitized programs. The case of AP suggests that not only can this feedback play an essential role in strengthening performance and improving efficiency and inclusion, but it can also draw program administrators’ attention to weak points and encourage them to explore other modalities for delivering services.

Further Reading

State of Aadhaar Report 2017-18 IDinsight. https://stateofaadhaar.in/wp-content/uploads/State-of-Aadhaar-Report_2017-18.pdf

Aadhaar and Food Security in Jharkhand. Dreze, Khalid, Kheera and Somanchi. Economic and Political Weekly, Volume 52 No. 10, December 2016. https://www.epw.in/journal/2017/50/special-articles/aadhaar-and-food-security-jharkhand.html

Digital Governance in Developing Countries: Beneficiary Experience and Perceptions of System Reform in Rajasthan. Gelb, Mukherjee and Navis. Center for Global Development Working Paper 489, 2018. /publication/digital-governance-developing-countries-beneficiary-experience-and-perceptions-system

Fuel Subsidy Reform in Developing Countries: Direct Benefit Transfer of LPG Cooking Gas Subsidy in India. Mittal, Mukherjee and Gelb. Center for Global Development Policy Paper 114, 2017. /publication/fuel-subsidy-reform-developing-countries-india

Digital Governance: Is Krishna a Glimpse of the Future? Aadil, Gelb, Giri, Mukherjee, Navis, and Thapliyal. Center for Global Development Working Paper 512, 2019. /publication/digital-governance-krishna-glimpse-future-working-paper

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.