Recommended

A sound financial regulatory framework is critical for minimizing the risk imposed by financial system fragility. In the world’s emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs), such regulation is also essential to support economic development and poverty reduction. Meanwhile, it is increasingly recognized that global financial stability is a global public good: recent decades have seen the development of new international financial regulatory standards, to serve as benchmarks for gauging regulation across countries, facilitate cooperation among financial supervisors from different countries, and create a level playing field for financial institutions wherever they operate. For the worldwide banking industry, the international regulatory standards promulgated by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) stand out for their wide-ranging scope and detail. Even though the latest Basel recommendations, adopted in late 2017 and known as Basel III, are, like their predecessors, calibrated primarily for advanced countries, many EMDEs are in the process of adopting and adapting them, and many others are considering it. They do so because they see it as in their long-term interest, but at the same time the new standards pose for them new risks and challenges.

A CGD Task Force assessed the implications of Basel III for EMDEs and provided recommendations for both international and local policymakers to make Basel III work for these economies. This brief summarizes the key findings and recommendations, while the full Task Force report can be accessed here.

Methodology

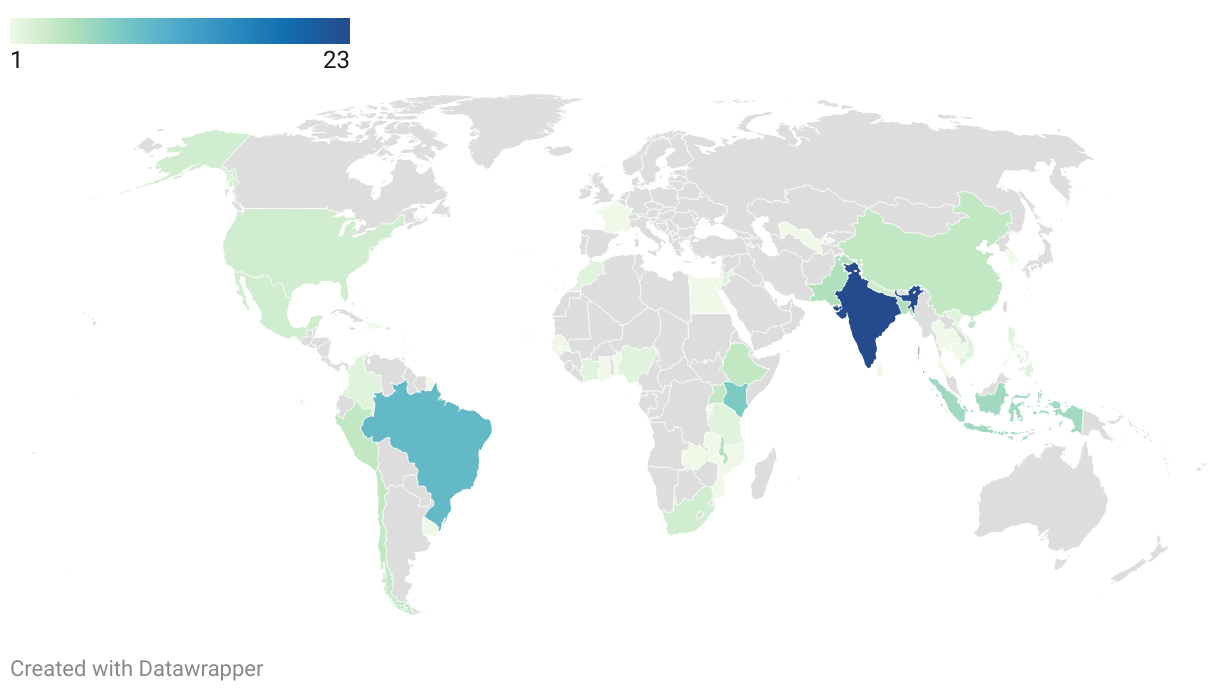

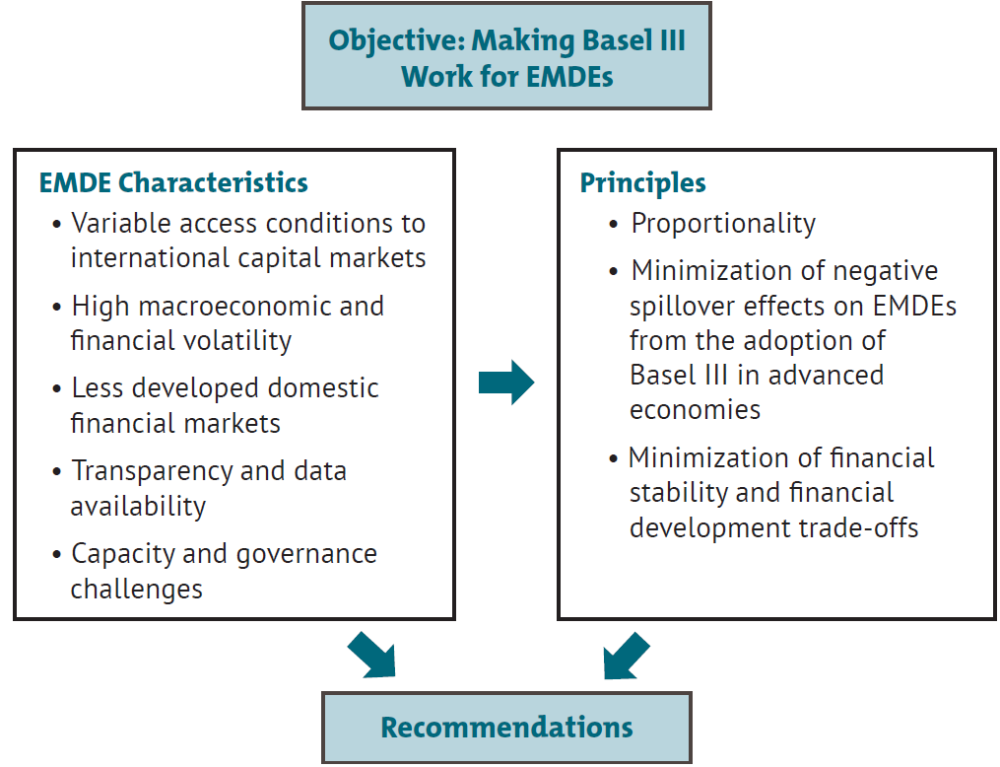

The Task Force devised a conceptual framework that combines, on the one hand, certain specific characteristics of EMDEs that distinguish them from advanced economies, with, on the other, a set of principles that aim to make Basel III work for EMDEs (see Figure 1). Although EMDEs as a group are quite heterogeneous, the financial systems in most show critical differences, relative to financial systems in advanced countries, that need to be considered when designing a regulatory framework: variable access conditions to international capital markets; high macroeconomic and financial volatility; less developed domestic financial markets; limited transparency; and capacity, institutional, and governance challenges.

The five characteristics help explain why the impact of international regulatory reforms, such as those under Basel III, is expected to be different in EMDEs than in advanced countries. They also imply the need for a differentiated approach to bank regulation to make Basel III work in these countries. Using these characteristics as a starting point, the Task Force’s analysis and recommendations build on three principles:

- Minimize the negative spillover effects of Basel III adoption in advanced countries

- Aim for proportionality in applying standards

- Minimize the trade-offs between financial stability and financial development

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework

Minimizing Potential Spillovers on EMDEs

Potential adverse spillovers on EMDEs from the adoption and implementation of Basel III in advanced economies can materialize in two ways. One is through effects on the volume, composition, and stability of cross-border financial flows; the other is through effects on financial stability and the level playing field between foreign bank affiliates and domestic banks.

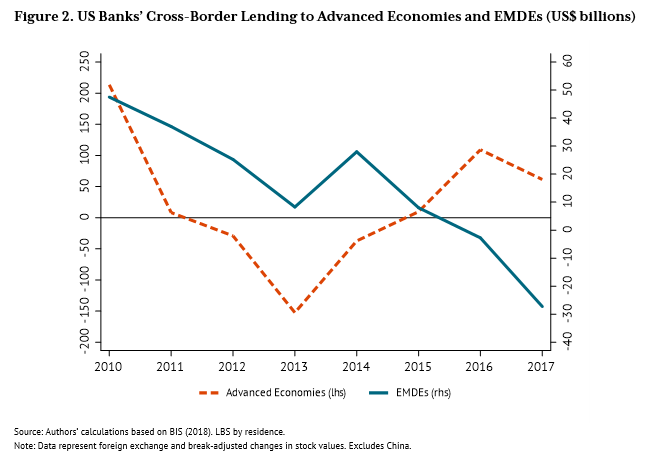

Since the global financial crisis of 2008–09, cross-border lending from global banks to EMDEs have fallen sharply, including from US banks, whose lending to advanced economies has recovered since 2014 (see Figure 2). This trend has been only partly countered by an increase in bond issuance by EMDEs and an increase in in South– South lending (lending from large banks in EMDEs to other EMDEs). While acknowledging the multiple factors behind this trend, we provide some insights (but no definite conclusions) supporting the view that the adoption of Basel III in advanced countries may have played a role.

Figure 2. US Banks’ Cross-Border Lending to Advanced Economies and EMDEs (US$ billions)

These recent trends have important policy implications, but also call for more analysis. Here it would be helpful if regulators from advanced economies, following the US Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council’s (FFIEC) example, made bank-level data on foreign exposures public, including on loans to EMDEs. This would allow the currently extremely limited research on the effects of Basel III on cross-border lending to EMDEs to be expanded. If these data cannot be made public, the Task Force recommends that the International Banking Research Network (IBRN), a group of researchers from over 30 central banks and multilateral institutions that analyzes issues pertaining to global banks, broaden and deepen their analysis on cross-border spillover effects for EMDEs.

Further assessment of cross-border spillover effects is also needed from multilateral organizations. We recommend that the World Bank follow up on a recent pilot and undertake more surveys on the impact of regulatory reforms, covering a large number of EMDEs on a regular basis (every two or three years). We also call for more case studies, in the form of evaluation assessments, as part of a surveillance scheme for the specific purpose of identifying these spillover effects as more EMDEs adopt the Basel Accord.

Concerning the shift from bank- to market-based borrowing by EMDEs, a crucial question is whether increased reliance on the latter provides a more stable source of external funding. For example, is the behavior of institutional investors that hold EMDE bonds more (or less) procyclical than that of international banks holding claims on these countries? Clarity on this issue would lead to appropriate recommendations that avoid exposing EMDEs to excessive risk while not unduly limiting their access to much-needed external sources of finance. Resolving these issues constitutes an important agenda for the IMF and other international financial institutions (IFIs).

The increase in South-South cross-border lending offers a number of advantages for EMDEs: it supports the internationalization (or in some cases regionalization) of their financial systems, which can lead to greater financial inclusion and, if well managed and supervised, to greater financial stability. However, observed weaknesses in the banking systems’ oversight of the Southern lenders, together with deficiencies in risk assessment mechanisms, indicate that important issues remain to be tackled to improve the quality and sustainability of this lending. Further, macroprudential regulations and policies designed to prevent overindebtedness and potential currency mismatches need to be in place, given the systemic risk that can arise.

Infrastructure finance, a specific type of cross-border flow, has received special attention in the discussion on the impact of Basel III, given the high infrastructure needs of many EMDEs. Although infrastructure finance in advanced countries recovered rapidly after the crisis and has since expanded further, it has stalled in the EMDEs as a group (see Figure 3). It is not yet clear whether Basel III can be associated with recent developments, but it does have the potential to influence bank funding for infrastructure across multiple dimensions. And even though many of the reforms under Basel III are not yet in effect, banks may have already responded to expected future regulatory changes (especially for long-term assets, banks price in future regulatory changes at origination even when those changes are to be phased in slowly). While surveys of practitioners and EMDE regulators have pointed to concerns about the effects of Basel III on infrastructure finance, opinions vary greatly about its real impact. This is another area where further research will be valuable.

Figure 3. Infrastructure Finance in Advanced Economies and EMDEs (US$ billions)

Finally, we commend current efforts to develop infrastructure as an asset class. If this eventually allows project financing to be developed in a more standardized fashion, and there is agreement on the different dimensions of risk and their quantification, it may become easier to issue securities backed by infrastructure projects, and regulators may be better able to assess the risks for banks’ lending to the special-purpose vehicles that often finance such projects. Given sufficient evidence on risks, lower risk weights for the computation of capital requirements might be appropriate for projects that comply with an agreed set of risk parameters.

The potential for spillover effects through the large presence of affiliates of global banks, relates to the competition between these affiliates and EMDEs’ domestic banks. Supervisors of global banks in advanced economies require that regulations, including Basel III, be applied and enforced on a consolidated basis, that is, to the entire banking group, including its foreign affiliates. But this can mean that the same sovereign exposure might get different regulatory treatment by home-country than by host-country supervisors. Thus, it is plausible that the same sovereign paper issued by an EMDE government could be treated as a foreign currency-denominated asset, with higher risk weight requirements, if held by a local subsidiary of a global bank, and as a local currency-denominated asset if held by a domestic bank. This, in turn, increases the cost to the subsidiary to hold the sovereign paper. Given the importance of these banks in the provision of liquidity of government securities, the financing costs of EMDE governments would face upward pressure. Although this issue has not changed from Basel II to Basel III, its relevance remains high.

We therefore recommend starting a process of analysis and intergovernmental discussion to identify additional conditions to be met by host countries that would encourage global banks and home-country supervisors to apply, at the consolidated level, host-country treatment to local currency-denominated sovereign exposures. One possibility is to agree on threshold values for a set of easily verifiable and widely available macrofinancial indicators (including, but not limited to, international credit ratings). For host countries whose indicators surpass the thresholds, home-country supervisors and global banks would accept, at the consolidated level, the host country’s regulatory treatment of these exposures.

Global banks from advanced economies are not the only banks with a significant presence in EMDEs through their affiliates. The increased role of cross-border South-South lending, discussed above, has been accompanied by an increasing presence of affiliates of emerging markets’ banks in other EMDEs, often within the same geographical region and involving new lenders. This poses additional regulatory challenges. To maximize the benefits, it is crucial that EMDE lenders achieve the highest standards of quality and transparency in their operations. In particular, the new lenders must display high transparency regarding their international lending and demonstrate that they have effective mechanisms for risk assessment when extending large amounts of loans, particularly to low-income countries. Appropriate mechanisms for resolving debt problems, should they arise, also need to be in place.

We further recommend the identification of a set of what we term R-SIBs—regional systemically-important banks—to be subject to a set of regulations combining elements from the Basel III recommendations for domestic systemically important banks (D-SIBs) with those for global systemically important banks (G-SIBs). Deeper cooperation between home and host supervisors in EMDEs is also called for, especially with respect to the quality of capital and workable cross-border resolution mechanisms and early-action processes. IFIs can play an important role here by providing technical assistance. Improved cross-border coordination between supervisors of advanced-economy global banks and supervisors in EMDEs is also needed.

Aiming for Proportionality

As already noted, the Basel III standards are designed and calibrated primarily for large cross-border banks in advanced economies. Maximizing the benefits of stability for EMDE financial systems requires that these standards be adapted to their circumstances. The complexity of Basel III makes it inherently difficult to implement; in addition, parts of it are less relevant to many EMDEs. Given their limited supervisory capacity, this complexity can invite regulatory arbitrage and regulatory capture. EMDE regulators therefore need to prioritize the key risks (including credit and liquidity risks) in their banking sectors, matching effort to supervisory capacity. Also, in areas where risk modeling requires data that are unavailable or costly to collect, or where modeling itself is costly and subject to high uncertainty (such as for market and operational risk), countries might consider using simple capital surcharges in lieu of these data-intensive models. On the other hand, we encourage the tapping of unused data sources, such as loan-level data from credit registries, to model credit risk weights to EMDE circumstances, as discussed below.

All that said, we caution against an excessive reliance on proportionality. A danger is that if different countries adapt regulations in very different ways, the whole idea of a common standard may be lost. Such “multipolar” proportionality could erode the level playing field and render cross-country comparisons and assessments more difficult, especially across groups of countries where financial integration is growing. To mitigate this risk, we recommend a regional approach, whereby groups of regulators across each EMDE region would agree on a set of proportional rules for their region. Thus, the principle of proportionality would be maintained but applied in a coordinated fashion among regulators whose financial systems share similar characteristics. Such a set of rules might include agreement on which Basel III approaches to apply, as well as how to adapt specific regulations. We also recommend that international standard-setting bodies develop a set of guiding principles for the development of proportional frameworks and work with these regional groups of regulators.

Moving from the general to the specific, we discuss how the proportionality principle can be applied to liquidity and capital requirements under Basel III. For example, simpler liquidity ratios might be called for if the data requirements for the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) and the net stable funding ratio (NSFR) are not easily fulfilled. On the other hand, the typical characteristics of EMDEs—especially their variable access to international capital markets, the shallowness of their interbank markets, and the high correlation in liquidity positions across banks—might make a centralized, systemic liquidity management tool necessary. Specifically, banks could be mandated to maintain a fraction of the liquid assets required to fulfill Basel III requirements with a centralized custodian such as the central bank. This would aid monitoring and would allow the relevant authorities to publicize the systemwide liquidity available, thus boosting market confidence and preventing systemic problems from occurring in the first place. These liquidity requirements should be remunerated and would form part of the Basel requirements.

Capital requirements in EMDEs are often “gold-plated”; that is, minimum capital requirements are set above those recommended by international standards so as to signal high regulatory quality. The Task Force calls instead for the proper calibration of risk weights where data are available. Where loan-level data are available, for example through credit registries, and supervisory skills are high, risk weights for credit exposures can be calibrated to country circumstances, thus better reflecting actual risk. Supervisors can then compare these country-specific calibrated risk weights with those under both the standardized and IRB approaches of Basel III before deciding on the weights to be prescribed. As already discussed, we do not advocate that every country develop its own risk weights, but instead call for regional or subregional arrangements when possible.

Another relevant aspect of Basel III’s capital requirements is the new countercyclical capital buffer, designed to protect the banking sector from periods of excessive credit growth associated with the build-up of system-wide risk. The credit-to-GDP gap (the deviation of the credit-to-GDP ratio from its trend) is recommended by the Basel Committee as the baseline for guiding decisions on the activation and release of the buffer. However, there are concerns about its effectiveness in many EMDEs (or indeed in many advanced countries), especially in countries where structural changes in the data are present. As the Basel Committee has suggested, the focus might have to be on other gauges, including real credit growth, measures of credit conditions (e.g., as gleaned from loan officer surveys), and corporate and household data.

Not only do capital and liquidity requirements as recommended by Basel III have to be adapted to the needs and capacities of EMDEs, but they, along with a core regulatory toolbox in advanced countries, might not be sufficient to address critical stability concerns specific to many EMDEs. For example, a high sensitivity to certain commodity prices (whether as exporter or importer) and high sectoral concentration can result in higher asset concentration on banks’ balance sheets and thus greater fragility and a higher probability of losses. Similarly, high price and exchange rate volatility can translate into volatility in banks’ liquidity and solvency positions, especially in financial systems that rely heavily on foreign-currency assets and funding. There might thus be a need for cruder instruments than proposed under Basel III, including lending and exposure restrictions such as already exist in some EMDEs. Such restrictions would go beyond single-exposure limits and could refer to sectoral, geographic, or foreign-currency lending exposures.

Minimizing Trade-offs between Financial Stability and Development

The social return on financial deepening is generally higher in EMDEs than in advanced economies and has to be balanced against stability needs. Thus, it is critical that a cost-benefit analysis precede introduction of any new regulatory standards, weighing the potential benefits of higher stability against the costs for regulators, regulated entities, and the economy. To smooth the transition to the new standards, regulators should announce the changes early and allow for long implementation periods, including a gradual introduction of tighter capital or liquidity requirements.

In the wake of the global financial crisis, the Basel III reforms also aim to reduce the role of commercial banks in capital markets so as to protect the core commercial segment of banking. For EMDEs, however, this might tend to reduce the efficiency and development of these still-growing markets, where banks can play an important role as market makers and participants.

In addition, tighter bank regulation and banks’ consequent retrenchment might create funding gaps for important sectors such as infrastructure finance. In economies with more advanced financial systems, these gaps can be filled by nonbank financial intermediaries, especially contractual savings institutions, which typically have long-term liabilities that need to be matched with long-term assets (such as life insurance companies, pension funds, and mutual funds), and public capital markets, but these are often underdeveloped in EMDEs and thus need strengthening as bank regulation tightens. The focus here should be on privately owned and managed, but regulated, institutions: excessive political interference in this process must be avoided. To call for the development of nonbank sources of funding is not to call for more government-owned and -managed development financial institutions. Whatever their advantages for financial deepening in theory, the experience with direct lending by these institutions in most EMDEs has not been positive.

Important though financial development is, the temptation to use regulatory subsidies, such as more favorable risk weights on capital requirements to alleviate the financing constraints of underserved groups, such as SMEs, must also be avoided. Such subsidization at best has little impact (e.g., in the case of the SME support factor in the European Union) and, at worst can increase system fragility. Rather than using stability-oriented regulatory tools, it would be better to use other, nonregulatory tools, such as partial-credit guarantee schemes.

Credit enhancements of this type can also support the provision of infrastructure finance. They can be applied by either international players (such as MDBs) or domestic players to improve the risk profile of bank lending for infrastructure finance through risk sharing and risk mitigation. Such tools can be effective if fairly priced, especially for lengthening maturities and thus better matching the maturities of assets and liabilities for developers. They should attract capital relief, but only in line with the credit rating of the guarantor. Although idiosyncratic risks can be guaranteed at the domestic level, systemic, country-level risks are best guaranteed by global players such as MDBs.

Beyond such market interventions, it is critical to strengthen the institutional framework that enables lending to credit-constrained sectors, including SMEs and infrastructure. Here the focus should be on the establishment and effective functioning of credit and collateral registries, reliable contract enforcement, strengthening the legal system at large, and a competitive economic environment.

More generally, to minimize the tension between the policy objectives of financial development and financial stability, we recommend strengthening the developmental objective of regulation and supervision of nonbank segments of the financial system as a secondary objective to thus rebalance the trade-off. Policy should also ensure a level playing field across different segments of the financial system: this means similar regulatory requirements for similar financial services, as long as the overall risk of the institutions offering the services is also similar. To further promote the development of nonbank financial institutions, countries could create a “champion” for nonbank long-term finance in the regulatory and political landscape. This would follow the example in some countries of financial inclusion champions, which focus on vetting policies and regulations so as to increase inclusion, and on launching new policy initiatives.

Further Recommendations

Finally, the Task Force also takes a forward-looking view on the process by which international regulatory standards are being designed and adopted.

a. Making standard setting more inclusive

Many EMDEs have shown themselves eager to adopt at least parts of Basel III, despite its having been developed primarily with large cross-border banks in advanced economies in mind. The BCBS should respond by opening its deliberations to more meaningful input from EMDEs. Although some EMDEs are already represented on the Basel Committee, and the greater role of the G20 opens the process to input from the largest ones, more needs to be done to address the interests of smaller and less developed EMDEs. One way would be to include non-G20 EMDEs on a rotating basis. Another would be to create additional chairs to represent certain groups of EMDEs, with rotating membership.

Although the current Basel III framework might not be appropriate for all EMDEs, adoption is often seen as an important signal to the international investor community. It might be worthwhile considering elevating other standards to fulfill such signaling functions instead. For example, compliance with the Basel Core Principles of Effective Supervision (BCP) is a prerequisite for effective implementation of the stricter Basel III recommendations. However, in many EMDEs, there are significant deficiencies in meeting key provisions of the BCPs. The IFIs (including the Basel Committee) could make explicit efforts to favor adoption of the BCP, not Basel III, as the primary signal of regulatory quality in EMDEs, to help change the widespread perception that compliance with Basel III is the right metric for EMDEs to follow. One way to go about this would be to set a regular timetable for assessment of individual EMDEs’ compliance with the BCPs, perhaps undertaken by the World Bank or the IMF. At present, BCP assessments are undertaken in the context of the FSAP, and not on a regular basis for many smaller developing economies, and the findings are published only with approval of the government.

b. Research and learning agenda

Because many of the effects of Basel III’s adoption for EMDEs are not yet fully understood, we also call for an expansive research agenda. We encourage both further research in the EMDEs themselves and more cooperation and exchange of information between EMDEs. Specifically, EMDE regulators need to deepen mechanisms for learning from their counterparts in other EMDEs as a complement to consultations with international standard-setting bodies. EMDE regulators could also coordinate among themselves on their adoption of Basel III, to identify problems and work on solutions that can be discussed with the standard-setting bodies. Regional associations of EMDE central banks could serve as an institutional setting for such coordination.

An important topic for research within EMDEs is the repercussions of Basel III for credit allocation in the real economy. Many EMDEs have readily available micro-level data for this purpose (e.g., credit registry data). Research initiatives similar to the IBRN, but in EMDEs, coordinated by, for example, regional associations of central banks or the regional development banks, can also be useful.

One specific area where research is needed is the use of macroprudential tools. Such tools are already part of the regulatory toolbox for EMDEs and complement the Basel III tools, but knowledge remains limited about what works and under what circumstances. We encourage more country-specific research and global cooperation among regulatory authorities in this area. EMDEs are—on average—well ahead of the advanced economies in the use of some macroprudential policy tools that address some of their sources of fragility.

In Sum

Basel III reflects lessons learned from recent crises, especially in advanced countries. It promises important benefits for financial stability, for both those countries and EMDEs. The Task Force report seeks to maximize those benefits for EMDEs, given the particularities of their financial systems. Its recommendations are directed both at EMDE policymakers considering how best to adjust Basel III to their economies’ needs, and at home supervisors of global banks whose lending to EMDEs, directly or through local affiliates, is influenced by Basel III. We have also addressed recommendations to the multilateral organizations, including the BCBS and the FSB, as well as the IMF, the World Bank, and regional development banks. One important recurring theme throughout the report is the need for all interested parties to continue to evaluate the impact of the new financial regulation on EMDEs, including through evaluations done in the EMDEs themselves.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.