Recommended

Event

HYBRID

October 05, 2023 11:00—12:30 PM EDT | 4 - 5.30 PM BSTSouth Asia has experienced unprecedented heatwaves this year, with temperatures soaring well above the usual seasonal highs, prompting school closures across the region. These incidents are emblematic of a growing global trend: educational institutions are having to adapt to the increasing frequency and intensity of climate and environmental crises.

Nearly a billion children live in countries highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Environmental shocks and long-term climate shifts impact children's wellbeing, yet our understanding of how education systems interact with these events is limited. South Asia in particular is susceptible to such shocks, and governments frequently mandate school closures in response to extreme heat and inclement weather. In this blog we examine past trends of educational responses to such events in the region.

1. Education systems often don’t respond to shocks, but when they do, they usually close schools

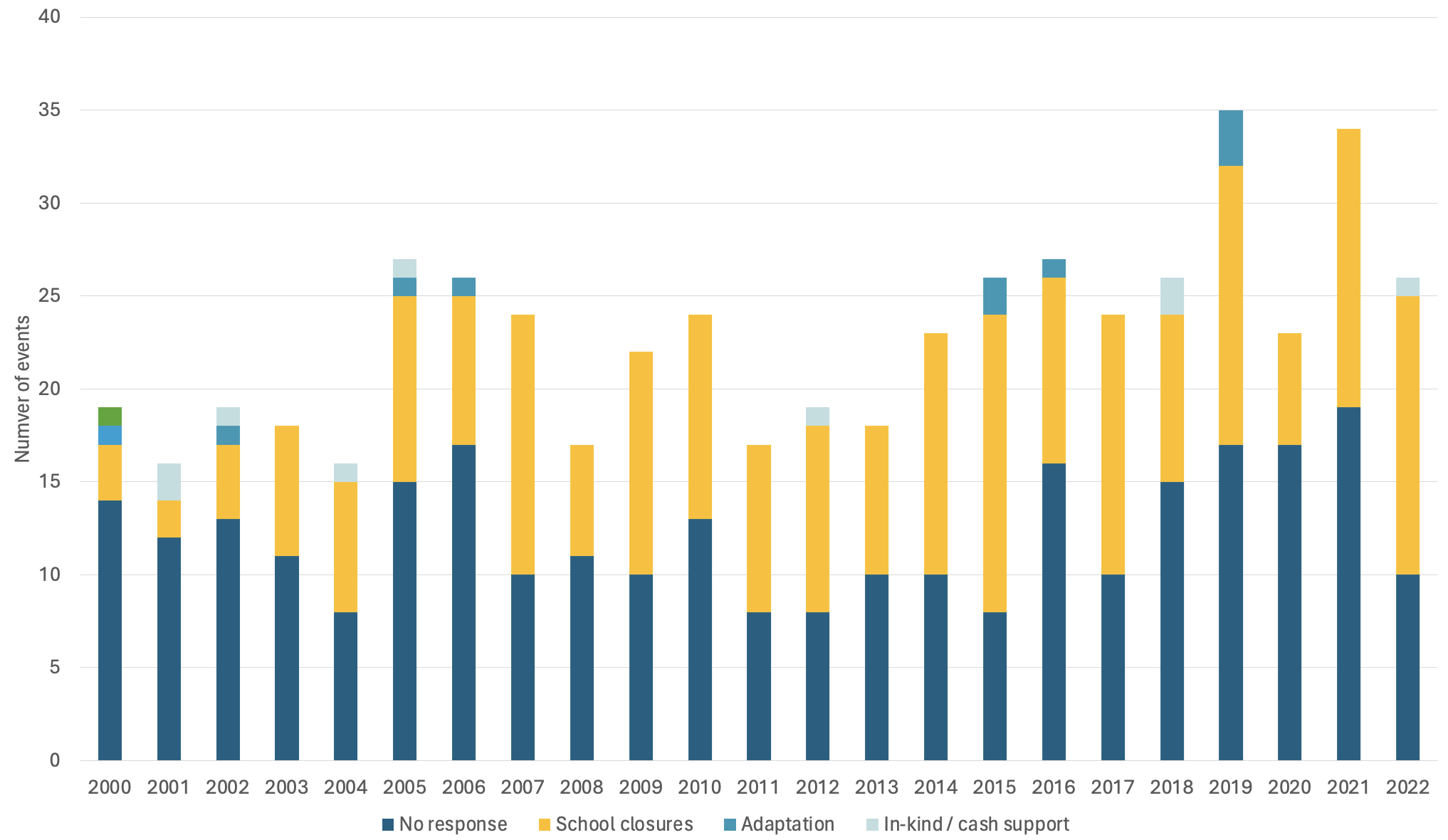

We recorded 532 shocks (including floods, heat and cold waves, periods of droughts, high pollution events, cyclones, earthquakes, avalanches, and tornadoes) and corresponding responses from education systems in the region from 2000 to 2022. Often schools don’t react to these events at all. When they do take action—it is to shut down. Other response categories we documented included adaptation measures (such as setting up temporary learning centres, providing remote or hybrid learning, and installing disaster-resilient infrastructure), and in-kind or cash support.

Figure 1: Number of events that resulted in an education system response, by response type over time, for South Asian countries

Note: The analysis uses publicly available online reports on climate change events and resulting actions, which means there is a high possibility that some instances are missed. Coverage is also thus lower for earlier years than for more recent periods.

The literature on school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic shows that they have severe and persistent effects on learning levels and human capital accumulation. Learning losses are higher for students from lower socio-economic backgrounds, which increases educational inequality. Especially for students in South Asia—where the most common remote learning support provided during COVID-19 closures was via low-tech, asynchronous modalities with limited reach and access for students—it is important for systems to consider how best to deliver education more effectively when schools must close to keep children safe.

Responses besides school closures are usually implemented by NGO or donor organisations. Within countries, Indian national and sub-national governments were more likely than NGOs or donors to be the ones pursuing policies that are not school closures, while in Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan, over 70 percent of these policies are pursued by NGOs or donors (more details in the background note).

2. There is wide variation in responses by different jurisdictions to the same shock

1. Air pollution

Air quality is internationally recognized as being hazardous when air quality index (AQI) reaches levels above 100. We find that when schools closed in the region because of pollution, air quality index almost always had to reach levels considered very unhealthy (201-300).

However, across regions there were different frequencies of responses to these high pollution events – Kolkata (India), Dhaka (Bangladesh) and Peshawar (Pakistan), even when reaching this threshold, didn’t order school closures due to pollution. New Delhi (India) and Lahore (Pakistan) responded to about a third and a half of these events with school closures, respectively (see Figure 2). Given these differences in response rates both across and within countries, it does not appear that governments have nationally or internationally coordinated response systems triggered by extreme events.

Figure 2: Number of periods with AQI levels between 201-300 per city and resulting policies

2. Extreme temperatures

Thresholds, when defined, tend to be localised: heatwaves, for instance, are usually defined by different temperature levels for each country, and often within countries. Further, not all events have clearly defined indicators of health risk (e.g. floods do not). Even for the same event, we find that different areas were affected but they did not all respond similarly.

For example, a heatwave in June 2019 caused schools to close (or delayed reopening after summer vacations) in Delhi, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh, but also affected Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Maharashtra, where schools did not close in response to the high temperatures. All three states reported deaths due to the heatwave and temperatures above 47 degrees Celsius, the threshold above which heatwaves are considered extreme by the India Meteorological Department. Similarly, a cold wave and snowfall in Pakistan in January 2020 led to extended winter vacations in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, but no education system response was recorded in three other provinces, where a total of over 100 deaths due to cold weather were reported.

3. Extreme events often affect the same regions repeatedly

Another concern for policymakers designing education system responses is the fact that extreme events often affect the same places over and over again (although these patterns are also becoming less predictable). Students and schools that are repeatedly affected by shocks are less able to develop resilience and implement adaptation plans. Climate shocks can not only be frequent, but also overlapping, deepening child deprivation and increasing inequality, and raising chances that education is stopped for good. Our analysis finds that specific provinces tend to be affected more often than others, based on data from the last ten years (see the example from India in Figure 3 below).

Understanding which regions are most affected by climate or environment shocks is essential for effective governance, risk reduction, and ensuring the safety and well-being of children at school. It enables policymakers to make informed decisions, allocate resources efficiently, and minimize the negative impacts of natural disasters, and to develop targeted strategies to boost resilience of systems and students to respond to these shocks.

Figure 3: Number of times students were affected by extreme events (2013-2023)

4. Estimations of number of students affected by these shocks are important but difficult to get right

It is remarkably hard to estimate the scale of impact from a natural disaster. Not all disasters are equal, and not all those affected are impacted equally. Children are particularly affected when exposed to shocks that disrupt their normal way of life, and those in more impoverished households or communities are worse off than their peers.

Although useful from a policy and political perspective to ascribe a number to the impact on children from a particular shock or event, it is equally important that this number not be generic or overstated. Unsurprisingly, the precision and reliability of publicly available information (such as from national statistics, NGO or government reports, and news articles) varies widely.

To achieve a credible estimate, we categorise the estimation of students affected by each shock by confidence level 1, 2 and 3, from least to most conservative. We then add weights smaller or equal to 1 for each and construct three estimates of the total number of students affected per year from least to most conservative. In the case of Bangladesh (depicted in Figure 4 below), applying these reliability weights results in a difference of nearly 700,000 children affected by extreme events in 2022.

Figure 4: Estimates of number of children affected by climate and environment shocks in Bangladesh, based on 3 scenarios.

Note: Check the background note for more details on the methodology.

Reliable estimates of the number of students affected by climate shocks are essential for immediate response, long-term planning, and ensuring the well-being and continuity of education for those affected. These estimates guide resource allocation, inform policies, and promote resilience in the face of a changing climate. Overstating the impact may contribute to public skepticism about the severity of the situation, making it harder to garner support and resources in an already constrained space.

What the trends tell us

Responses to shocks vary greatly within countries and regions, and there is no clear international standard prescribed or followed. With ever increasing events of high heat and pollution across the region, prompting school closures more frequently than before, education stakeholders must reconsider the suite of available policies, look for ways to standardize responses across regions, and consider questions of policy scalability and cost-effectiveness across affected regions and in response to multiple events. Further analysis of the scope of shocks and responses can help researchers, policymakers and donors better support the education systems most affected by climate and environment events, and design climate-smart education and social protection systems that can foster schools’ and students’ resilience and adaptability.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.